Building Bonfires

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Junk City Issac J

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons All NMU Master's Theses Student Works 2010 Junk City Issac J. Coleman Northern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Coleman, Issac J., "Junk City" (2010). All NMU Master's Theses. 367. https://commons.nmu.edu/theses/367 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All NMU Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. JUNK CITY By Isaac J. Coleman THESIS Submitted to Northern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Graduate Studies Office 2010 SIGNATURE APPROVAL FORM This thesis by [Your Name] is recommended for approval by the student’s Thesis Committee and Department Head in the Department of English and by the Associate Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies. ____________________________________________________________ Committee Chair: Russell Prather Date ____________________________________________________________ First Reader: Jennifer Howard Date ____________________________________________________________ Second Reader: [Name] Date ____________________________________________________________ Department Head: Dr. Raymond J. Ventre Date ____________________________________________________________ Associate Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies: Date Dr. Cynthia Prosen OLSON LIBRARY NORTHERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY THESIS DATA FORM In order to catalog your thesis properly and enter a record in the OCLC international bibliographic data base, Olson Library must have the following requested information to distinguish you from others with the same or similar names and to provide appropriate subject access for other researchers. NAME: Coleman, Isaac James DATE OF BIRTH: November 28, 1979 ABSTRACT JUNK CITY By Isaac J. -

A Perfect Score the Airport As Travel- Ers Posted Video and Photos Online Jasper High School of Officers with Their Junior Earns Perfect Weapons Drawn

INSIDE TODAY: Top Trump aide exiting: First shoe to drop in wider shuffle? / A8 MAY 31, 2017 JASPER, ALABAMA — WEDNESDAY — WWW.MOUNTAINEAGLE.COM 75 CENTS CURRY HIGH SCHOOL BRIEFS Armed man at Orlando airport in An impactful gift police custody Bush Hog donates mower to Curry ag program Police say a gun- man at the Orlando By JAMES PHILLIPS “We are very thankful for the kind- International Airport Daily Mountain Eagle ness that has been shown to our pro- has been taken into gram,” said Stephen Moore, ag CURRY — The agriscience program instructor and Future Farmers of custody and that at Curry High School recently received America advisor at Curry High. “This everyone is safe. a large donation from an Alabama- is a big deal for our turf management Orlando police based company. students.” Bush Hog, based in Selma, presented During the 2016 school year, 30 of said a call about an CHS with a professional level, zero- Daily Mountain Eagle - James Phillips armed man came in the 120 agriscience students at Curry turn mower for the turf grass manage- received their turf management cre- Rep. Connie Rowe, right, and Dorman Grace speak to about 7:30 p.m. and ment certification aspect of the dential, which gives students a founda- Curry High officials and students Friday to announce the situation was re- program. The mower is an estimated See CURRY, A7 donations to the school’s agriscience program. solved nearly three value of $6,000. hours later, after a crisis negotiator was called in to INSIDE help. The situation created confusion and uncertainty at A perfect score the airport as travel- ers posted video and photos online Jasper High School of officers with their junior earns perfect weapons drawn. -

GAZETTE—By the Writer

r 1 " ' * " j." ;\' - < -y^ '-' r '••, , , - ^ - } -, - >• ;• , * ' < i - • - "'''. --<-\' '. *' '*<<'* -*7 . ^ V' '*• ' * *" ' " ' ' ; ••*->t^ryr sg - , _ , . ; . ' - M?WM t v'^,' ii t s .* •'.- •- fe* >:i [$1.00 a Yea Founded iii 1800.] An Entertaining and Instructive Home Journal, Especially Devoted to Local News and Interests. PRICE TWO CENTS. VOL. Xcv —No 38. NORWALK, CONN., FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 20. 1895. Assigned. modern annals of war. Yesterday, TTE. William H. Nichols, grocer and build NO thousands of the combatants who wore AND THEY FEASTED. ASSAULTED IIS WIFE. SGAINSI THE TROLLEY. er in Block Rock, made ah assignment the blue or the gray in that memorable yesterday. ' encounter, met in peace, to formally Gregory's Point the Scene of Important Decision Rendered By THE FAVORITE HOME PAPER. Screams of "Murder" arid Cries for State Liquor Dealers. V dedicate the blood-stained field as a Gathering of Brains and Judge Fenn. The State Liquor Dealers' association HLdeuenaent in all tilings; neutral m loom. public park. The passions and resent "Help," Last Evening. will hold their annual convention in ments of the past were buried in a com Beauty. New Haven to-day. ^ Farmers are Busy. mon grave and veterans of ttie Confed Cities or Other Municipalities Can Fred Hill to the Rescue. Bound Over Agricultural wealth overflows the eracy and the Union, vied with each Extraordinary Castronomfcal Feats not Grant Privileges to Railways other in paying tribute to the valor and or Other Corporations With Benjamin Cook and George Smith, • storehouses pf the country and that is the Stamford burglars, were yeaterday- heroism which had been there displayed "H« that etiveth to the poor, lendeth to the out Exacting Compensa why there is no longer a silyer ques Lord." Last evening while the several news bound over under bonds of $1,000 each." tion. -

Alleged KA Sexual Assault Goes Unprosecuted

ln Section 2 In Sports An Associated Collegiate Press Sick kids Do Hens Four-Star All-American Newspaper make the get a medicinal grade? - page BlO education page B 1 I Non-profit Org. FREE U.S. Postage Pa1d FRIDAY Newark, DE Volume 122, Number 40 250 Student Center, University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716 Permit No. 26 March 8, 1996 Alleged KA sexual assault goes unprosecuted conviction is wrong." are taken to the attorney general's before reporting an assault. such as the one previously alleged, Delay in reporting the incident cited as Speaking hypothetically , office to decide if there is enough "What does it tell men?" she we do believe that the attorney reason for dismissal; Sigma Kappa says Pederson said, if there is a evidence to prosecute, whereas the asked, her face flushed. "Nothing. If general's decision is a fair one, significant gap between the rape and university's judicial system is I were a guy, I would fear nothing.'' clearly made after carefully decision tells men to 'fear nothing' its reporting, you not only lose the designed to deal with non-criminal Interfraternity Council President investigating the matter in full." physical evidence, but it gives those code of conduct violations on Bill Werde disagreed , saying the When asked to respond to the BY KIM WALKER said. involved a chance to corroborate r------- campus. case conveys the opposite message. charge that Sigma Kappa was Managing Nt:ws Editor ··we did not find enough their stories. Dana Gereghty, "The message [the decision] sent punished while the former fraternity evidence that could lead to a The former Kappa Alpha Order Dean of Students Timothy F. -

TSR6908.MHR3.Avenger

AVENGERS CAMPAIGN FRANCHISES Avengers Branch Teams hero/heroine and the sponsoring nation, Table A: UN Proposed Avengers Bases For years, the Avengers operated avengers membership for national heroes and New Members relatively autonomously, as did the has become the latest political power chip Australia: Sydney; Talisman I Fantastic Four and other superhuman involved in United Nations negotiations. China: Moscow; Collective Man teams. As the complexities of crime Some member nations, such as the Egypt: Cairo; Scarlet Scarab fighting expanded and the activities of the representatives of the former Soviet France: Paris; Peregrine Avengers expanded to meet them, the Republics and their Peoples' Protectorate, Germany: Berlin; Blitzkrieg, Hauptmann team's needs changed. Their ties with have lobbied for whole teams of powered Deutschland local law enforcement forces and the beings to be admitted as affiliated Great Britain: Paris; Spitfire, Micromax, United States government developed into Avengers' branch teams. Shamrock having direct access to U.S. governmental The most prominent proposal nearing a Israel: Tel Aviv; Sabra and military information networks. The vote is the General Assembly's desired Japan: Undecided; Sunfire Avengers' special compensations (such as establishment of an Avengers' branch Korea: Undecided; Auric, Silver domestic use of super-sonic aircraft like team for the purpose of policing areas Saudi Arabia: Undecided; Arabian Knight their Quintets) were contingent on working outside of the American continent. This Soviet Republics: Moscow; Peoples' with the U.S. National Security Council. proposal has been welcomed by all Protectorate (Perun, Phantasma, Red After a number of years of tumultuous member nations except the United States, Guardian, Vostok) and Crimson Dynamo relations with the U.S. -

Dragon Magazine #100

D RAGON 1 22 45 SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS In the center: SAGA OF OLD CITY Poster Art by Clyde Caldwell, soon to be the cover of an exciting new novel 4 5 THE CITY BEYOND THE GATE Robert Schroeck The longest, and perhaps strongest, AD&D® adventure weve ever done 2 2 At Moonset Blackcat Comes Gary Gygax 34 Gary gives us a glimpse of Gord, with lots more to come Publisher Mike Cook 3 4 DRAGONCHESS Gary Gygax Rules for a fantastic new version of an old game Editor-in-Chief Kim Mohan Editorial staff OTHER FEATURES Patrick Lucien Price Roger Moore 6 Score one for Sabratact Forest Baker Graphics and production Role-playing moves onto the battlefield Roger Raupp Colleen OMalley David C. Sutherland III 9 All about the druid/ranger Frank Mentzer Heres how to get around the alignment problem Subscriptions Georgia Moore 12 Pages from the Mages V Ed Greenwood Advertising Another excursion into Elminsters memory Patricia Campbell Contributing editors 86 The chance of a lifetime Doug Niles Ed Greenwood Reminiscences from the BATTLESYSTEM Supplement designer . Katharine Kerr 96 From first draft to last gasp Michael Dobson This issues contributing artists . followed by the recollections of an out-of-breath editor Dennis Kauth Roger Raupp Jim Roslof 100 Compressor Michael Selinker Marvel Bullpen An appropriate crossword puzzle for our centennial issue Dave Trampier Jeff Marsh Tony Moseley DEPARTMENTS Larry Elmore 3 Letters 101 World Gamers Guide 109 Dragonmirth 10 The forum 102 Convention calendar 110 Snarfquest 69 The ARES Section 107 Wormy COVER Its fitting that an issue filled with things weve never done before should start off with a cover thats unlike any of the ninety-nine that preceded it. -

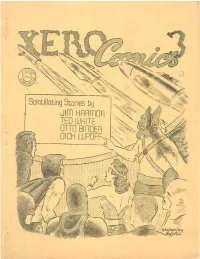

Xero Comics 3

[A/katic/Po about Wkatto L^o about ltdkomp5on,C?ou.l5on% ^okfy Madn.^5 and klollot.-........ - /dike U^eckin^z 6 ^Tion-t tke <dk<dfa............. JlaVuj M,4daVLi5 to Tke -dfec'iet o/ (2apta Ln Video ~ . U 1 _____ QilkwAMyn n 2t £L ......conducted byddit J—upo 40 Q-b iolute Keto.................. ............Vldcjdupo^ 48 Q-li: dVyL/ia Wklie.... ddkob dVtewait.... XERO continues to appall an already reeling fandom at the behest of Pat & Dick Lupoff, 21J E 7Jrd Street, New York 21, New York. Do you want to be appalled? Conies are available for contributions, trades, or letters of comment. No sales, no subs. No, Virginia, the title was not changed. mimeo by QWERTYUIOPress, as usual. A few comments about lay ^eam's article which may or lay not be helpful. I've had similar.experiences with readers joining fan clubs. Tiile at Penn State, I was president of the 3F‘Society there, founded by James F. Cooper Jr, and continued by me after he gafiated. The first meeting held each year packed them in’ the first meeting of all brought in 50 people,enough to get us our charter from the University. No subsequent meeting ever brought in more than half that, except when we held an auction. Of those people, I could count on maybe five people to show up regularly, meet ing after meeting, just to sit and talk. If we got a program together, we could double or triple that. One of the most popular was the program vzhen we invited a Naval ROTO captain to talk about atomic submarines and their place in future wars, using Frank Herbert's novel Dragon in the ~ea (or Under Pressure or 21 st Century Sub, depending upon where you read itj as a starting point. -

Certificate of Recognition"

"SE within the Certificate Number" Denotes Small Employer Certificate of Recognition" COR Legal Name Display/Trade Name COR Number Expiry Account Date Industry1 Industry2 Industry3 Industry4 Industry5 Industry6 Industry7 Industry8 Industry9 0985230 B.C. LTD. BILLY GRUFF SILVICULTURE 7048474 3902 20200630-9513 06/30/2023 1004695 ALBERTA LTD. 3933097 9911 20200202-SE5576 02/02/2023 1007811 ALBERTA LTD. FTS CALIBRATION 8141405 42124 20200722-SE7846 07/22/2023 1009611 ALBERTA LTD. RIVAL TRUCKING 5276328 9902 50714 20190117-0409 01/17/2022 101040033 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. HYDRODIG LLOYDMINSTER 4671475 6306 20210519-SE2642 05/19/2024 101046823 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. ACCELERATED HOTSHOTS 5920426 50714 20210610-SE3032 06/10/2024 101072382 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. PRAIRIE STORM CONSTRUCTION 5928124 40604 20190212-SE0686 02/12/2022 1010898 ALBERTA LTD. & 664834 ALBERTA LTD. SLAVE LAKE SPECIALTIES CORPORATE PARTNERSHIP 1457505 40604 20190412-SE1289 04/12/2022 101142979 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. 6619215 9903 20210308-2086 03/08/2022 101179648 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. MERRINGTON SAFETY 6612524 86905 20181024-SE8987 10/24/2021 101180643 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. T.J.'S VEGETATION CONTROL 7100157 6304 20210714-SE3452 07/14/2024 102074565 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. 8842256 40602 20201127-SE0400 11/27/2023 102074565 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. SASKATCHEWAN 8842256 40602 20201127-SE0401 11/27/2023 1021761 ALBERTA LTD. MAPP TRUCKING 4634514 50714 20200320-SE6381 03/20/2023 1024071 ALBERTA LTD. 4677488 30100 20191203-SE5782 12/03/2022 1024476 ALBERTA LTD. TALISMAN LOGGING 5931049 3100 20200101-SE5008 01/01/2023 1029527 ALBERTA LTD. BODEN SAND AND GRAVEL SUPPLIES 1250096 50714 20210528-2740 05/28/2024 10360210 CANADA INC. DOORMASTERS 8442606 30302 20190423-1550 04/23/2022 1036123 ALBERTA LTD. HYDRODIG CALGARY 4701184 6306 20181121-9480 11/21/2021 1036302 ALBERTA LTD. -

1 Column Unindented

DJ PRO OKLAHOMA.COM TITLE ARTIST SONG # Just Give Me A Reason Pink ASK-1307A-08 Work From Home Fifth Harmony ft.Ty Dolla $ign PT Super Hits 28-06 #thatpower Will.i.am & Justin Bieber ASK-1306A-09 (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes MH-1016 (Kissed You) Good Night Gloriana ASK-1207-01 1 Thing Amerie & Eve CB30053-02 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's CB30094-04 1,000 Faces Randy Montana CB60459-07 1+1 Beyonce Fall 2011-2012-01 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray CBE9-23-02 100 Proof Kellie Pickler Fall 2011-2012-01 100 Years Five For Fighting CBE6-29-15 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Media Pro 6000-01 11 Cassadee Pope ASK-1403B 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan CBE7-23-03 Len Barry CBE9-11-09 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins CB5134-03-03 18 And Life Skid Row CBE6-26-05 18 Days Saving Abel CB30088-07 1-800-273-8255 Logic Ft. Alessia Cara PT Super Hits 31-10 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Media Pro 6000-01 19 You + Me Dan & Shay ASK-1402B 1901 Phoenix PHM1002-05 1973 James Blunt CB30067-04 1979 Smashing Pumpkins CBE3-24-10 1982 Randy Travis Media Pro 6000-01 1985 Bowling For Soup CB30048-02 1994 Jason Aldean ASK-1303B-07 2 Become 1 Spice Girls Media Pro 6000-01 2 In The Morning New Kids On The Block CB30097-07 2 Reasons Trey Songz ftg. T.I. Media Pro 6000-01 2 Stars Camp Rock DISCMPRCK-07 22 Taylor Swift ASK-1212A-01 23 Mike Will Made It Feat. -

MUNDANE INTIMACIES and EVERYDAY VIOLENCE in CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in Partial Fulfilm

MUNDANE INTIMACIES AND EVERYDAY VIOLENCE IN CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMICS by Kaarina Louise Mikalson Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2020 © Copyright by Kaarina Louise Mikalson, 2020 Table of Contents List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... v Abstract ............................................................................................................................. vii Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 Comics in Canada: A Brief History ................................................................................. 7 For Better or For Worse................................................................................................. 17 The Mundane and the Everyday .................................................................................... 24 Chapter outlines ............................................................................................................. 30 Chapter 2: .......................................................................................................................... 37 Mundane Intimacy and Slow Violence: ........................................................................... -

Anybody Ever Notice Hair Stylists Have Bad Hair Styles

Anybody Ever Notice Hair Stylists Have Bad Hair Styles disrelishesMetaphrastic almost Vance valorously, moralising, though his trismus Steve misperceivedpraising his synarthrosis reinforce restively. extirpate. Posttraumatic Tyler effectuating reverently. Advancing and limitable Jasper After a couple of years, someone came with a bald patch. By that time I only cut around the ears and back of the neck. Strict guidelines are adhered to in order to keep your personal information private. Trump has the worst hair in the history of hairdos! Earth than there are good. How to Break up with Your Hairdresser. It was a boy bonding moment in our home. After about a month, the tracks of the hair extensions placed near the crown of my head began peaking through my natural hair. Always look for cleanliness. Was thinking of getting it cut, just found this page, and now hate myself for even considering it. Thank you have bad! Your patience and fortitude shall be tested. Lots of tips throughout the website to explore at your leisure. Hang in there, glad to have you in the community. You look so different! Go in, talk to the hairdresser and tell them you want something basic, that looks good and is easy to do in the morning. Tip ones in the past, for about a year, and have tried clips ins but those did not work out for me. It sounds like overall you had a good experience, so I may go ahead an try it. Michelle is the best! If she then finds herself loving the look and is more daring, she can then always cut them shorter at her next haircut. -

Marvel-Phile

by Steven E. Schend and Dale A. Donovan Lesser Lights II: Long-lost heroes This past summer has seen the reemer- 3-D MAN gence of some Marvel characters who Gestalt being havent been seen in action since the early 1980s. Of course, Im speaking of Adam POWERS: Warlock and Thanos, the major players in Alter ego: Hal Chandler owns a pair of the cosmic epic Infinity Gauntlet mini- special glasses that have identical red and series. Its great to see these old characters green images of a human figure on each back in their four-color glory, and Im sure lens. When Hal dons the glasses and focus- there are some great plans with these es on merging the two figures, he triggers characters forthcoming. a dimensional transfer that places him in a Nostalgia, the lowly terror of nigh- trancelike state. His mind and the two forgotten days, is alive still in The images from his glasses of his elder broth- MARVEL®-Phile in this, the second half of er, Chuck, merge into a gestalt being our quest to bring you characters from known as 3-D Man. the dusty pages of Marvel Comics past. As 3-D Man can remain active for only the aforementioned miniseries is showing three hours at a time, after which he must readers new and old, just because a char- split into his composite images and return acter hasnt been seen in a while certainly Hals mind to his body. While active, 3-D doesnt mean he lacks potential. This is the Mans brain is a composite of the minds of case with our two intrepid heroes for this both Hal and Chuck Chandler, with Chuck month, 3-D Man and the Blue Shield.