Introduction to Zen Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Prefazione Teisho

Tetsugen Serra Zen Filosofia e pratica per una vita felice varia 3 08/05/19 10:45 SOMMARIO Prefazione . .9 Teisho . .9 Introduzione . .13 PARTE PRIMA CENNI STORICI DEL BUDDISMO ZEN . .17 Bodhidharma . .20 Hui Neng . .21 Dogen Kigen . .21 Keizan Jokin . .22 Il nostro lignaggio . .22 Harada Daiun Sogaku . .22 Ban Roshi . .23 Tetsujyo Deguchi . .24 LO ZEN: FILOSOFIA, RELIGIONE O STILE DI VITA? . .25 Filosofia zen . .25 Lo Zen come stile di vita . .28 PARTE SECONDA LA PRATICA ZEN . .33 Che cos’è la mente? . .34 Che cosa vuol dire risvegliarsi alla natura della propria vita? . .34 Che cos’è la consapevolezza? . .36 Che cos’è la meditazione? . .36 Che cos’è lo stato meditativo? . .37 4 4 08/05/19 10:46 COME SI MEDITA . .39 Perché si medita seduti . .39 Come accordare il corpo . .40 I Mudra nello Zen. Postura delle mani . .45 ZAZEN . .49 Come accordare il respiro . .49 Prima meditazione . .52 Occhi e nuca . .53 Bocca . .53 Collo, spalle e braccia . .54 Addome e gambe . .55 Kinhin, una meditazione speciale . .57 Le quattro meditazioni zazen . .60 Susokukan, contare i respiri da uno a dieci . .61 Zuisokukan, seguire i respiri . .66 Shikantaza, il puro essere . .67 Koan, le domande . .68 La pratica in un tempio zen . .70 Shin Getsu . .71 L’abito fa in monaco . .71 Nello Zendo . .72 Shakyamuni . .75 Dokusan, l’incontro diretto con il maestro . .78 PARTE TERZA MEDITARE A CASA . .83 Come creare il vostro Dojo . .83 L’immagine . .84 I fiori . .84 L’incenso . .85 La campana . .86 Il rituale . -

Lineage-Patriarchen-Soto-Zen.Pdf

De lineage van de Patriarchen Sōtō Zen 1. Bibashi Butsu Daioshō 2. Shiki Butsu Daioshō 3. Bishafu Butsu Daioshō 4. Kuruson Butsu Daioshō 5. Kunagommuni Butsu Daioshō 6. Kashō Butsu Daioshō 7. SHAKAMUNI BUTSU DAIOSHO –> (Shakyamuni, Gautama, Siddhata, ca. 563 v.C. - 483 v.C.) 8. Makakashō Daioshō 9. Ananda Daioshō 10. Shōnawashu Daioshō 11. Ubakikuta Daioshō 12. Daitaka Daioshō 13. Mishaka Daioshō 14. Bashumitsu Daioshō 15. Butsudanandai Daioshō 16. Fudamitta Daioshō 17. Barishiba Daioshō 18. Funayasha Daioshō 19. Anabotei Daioshō 20. Kabimora Daioshō 21. Nagyaharajunya Daiosho (Nagarjuna) 22. Kanadaiba Daioshō 23. Ragorata Daioshō 24. Sōgyanandai Daioshō 25. Kayashata Daioshō 26. Kumorata Daioshō 27. Shayata Daioshō 28. Bashubanzu Daioshō 29. Manura Daioshō 30. Kakurokuna Daioshō 31. Shishibodai Daioshō 32. Bashashita Daioshō 33. Funyomitta Daioshō 34. Hannyatara Daioshō 35. BODAIDARUMA DAIOSHO (Bodhidharma, P'u-t'i-ta-mo, Daruma, Bodaidaruma, ca. 470-543) 36. Taisō Eka Daioshō (Hiu-k'o, 487-593) 37. Kanchi Sōsan Daioshō (Seng-ts'an, gest. 606 ?) 38. Daii Dōshin Daioshō (Tao-hsin, 580-651) 39. Daiman Kōnin Daioshō (Gunin, Hung-jen, 601-674) 40. Daikan Enō Daioshō (Hui-neng, 638-713) 41. Seigen Gyōshi Daioshō (Ch'ing-yuan Hsing-ssu, 660-740) 42. Sekitō Kisen Daioshō (Shih-t'ou Hsi-ch'ein, 700-790) 43. Yakusan Igen Daioshō (Yüeh-shan Wei-yen, ca. 745-828) 44. Ungan Donjō Daioshō (Yün-yen T'an-shing, 780-841) 45. Tozan Ryokai Daioshō (Tung-shan Liang-chieh, 807-869) 46. Ungo Doyo Daioshō (Yün-chü Tao-ying, gest. 902) 47. Dōan Dōhi Daioshō 48. Dōan Kanshi Daioshō 49. Ryōzan Enkan Daioshō (Liang-shan Yüan-kuan) 50. -

Research Article

Research Article Journal of Global Buddhism 2 (2001): 139 - 161 Zen in Europe: A Survey of the Territory By Alione Koné Doctoral Candidate Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Science Sociales (Paris) [email protected] © Copyright Notes Digitial copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no charge is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format with the exception of a single copy for private study requires the written permission of the author. All enquries to [email protected] http://jgb.la.psu.edu Journal of Global Buddhism 139 ISSN 1527-6457 Zen in Europe: A Survey of the Territory By Alioune Koné Doctoral Candidate Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (Paris) [email protected] Zen has been one of the most attractive Buddhist traditions among Westerners in the twentieth century. Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese teachers have created European organizations in the past forty years, and some of their students have started teaching. While their American counterparts are well documented in the growing literature on the making of a Western Buddhism, the European groups are less known.(1) This paper aims at highlighting patterns of changes and adaptations of Zen Buddhism in Europe. It proposes an overview of European Zen organizations and argues that an institutional approach can highlight important aspects of the transplantation of Zen Buddhism into a new culture. A serious shortcoming of such an endeavor was pointed out in a 1993 conference held in Stockholm. A group -

Great Teacher Mahapajapati Gotami

Zen Women A primer for the chant of women ancestors used at the Compiled by Grace Schireson, Colleen Busch, Gary Artim, Renshin Bunce, Sherry Smith-Williams, Alexandra Frappier Berkeley Zen Center and Laurie Senauke, Autumn 2006 A note on Romanization of Chinese Names: We used Pinyin Compiled Fall 2006 for the main titles, and also included Wade-Giles or other spellings in parentheses if they had been used in source or other documents. Great Teacher Mahapajapati Gotami Great Teacher Khema (ma-ha-pa-JA-pa-tee go-TA-me) (KAY-ma) 500 BCE, India 500 BCE, India Pajapati (“maha” means “great”) was known as Khema was a beautiful consort of King Bimbisāra, Gotami before the Buddha’s enlightenment; she was his who awakened to the totality of the Buddha’s teaching after aunt and stepmother. After her sister died, she raised both hearing it only once, as a lay woman. Thereafter, she left Shakyamuni and her own son, Nanda. After the Buddha’s the king, became a nun, and converted many women. She enlightenment, the death of her husband and the loss of her became Pajapati’s assistant and helped run the first son and grandson to the Buddha’s monastic order, she community of nuns. She was called the wisest among all became the leader of five hundred women who had been women. Khema’s exchange with King Prasenajit is widowed by either war or the Buddha’s conversions. She documented in the Abyakatasamyutta. begged for their right to become monastics as well. When Source: Therigata; The First Buddhist Women by Susan they were turned down, they ordained themselves. -

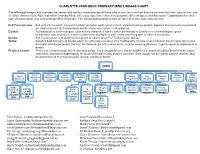

JOKO CHARLOTTE JOKO BECK ORDINARY MIND LINEAGE CHART Ezra Bayda: [email protected] Gary Nafstad (No Contact) Larry Chris

CHARLOTTE JOKO BECK ORDINARY MIND LINEAGE CHART The following lineage chart provides the names and contact information for all those who at one time received dharma transmission from Joko or from one of Joko's dharma heirs. Note that within Ordinary Mind, different people have chosen to designate different types of transmission. Explanations for each type of transmission may vary amongst different people. The following description is only an attempt to give some idea of each. Full Transmission: Full authority to teach, transmit to others and give Jukai. Given to both ordained and lay people. Appears that everyone transmitted by Joko received Full Transmission whether they were or were not ordained. Denkai: Authorization to teach and give Jukai but not transmit. It can be either preliminary to Denbo or a terminal degree, given to someone who teaches in a context other than having their own zendo and being able to name a successor. Denbo: Full Transmission with authority to transmit to others (as in Full Transmission above.) Shiho: Includes both Denkai and Denbo which are often done at same time.Traditionally, Denkai means transmit the precepts (kai means precepts) and denbo means transmit the Dharma (bo is the same as ho in shiho meaning dharma). It can be given to ordained or lay people. Practice Leader: This is not a transmission and is not listed below. It is a recognition of a senior student as a leader who gives dharma talks, zazen instruction, and takes responsibility for much of the day to day practice activities. S/he usually works closely with the teacher. -

Zen and Japanese Culture Free

FREE ZEN AND JAPANESE CULTURE PDF Daisetz T. Suzuki,Richard M. Jaffe | 608 pages | 22 Sep 2010 | Princeton University Press | 9780691144627 | English | New Jersey, United States Influence of Zen Buddhism in Japan - Travelandculture Blog This practice, according to Zen proponents, gives insight into one's true natureor the emptiness of inherent existence, which opens the way to a liberated way of living. With this smile he showed that he had understood the wordless essence of the dharma. Buddhism was introduced to China in the first century CE. He was the 28th Indian patriarch of Zen and the first Chinese patriarch. Buddhism was introduced in Japan in the 8th century CE during the Nara period and the Heian period — This recognition was granted. InEisai traveled to China, whereafter he studied Tendai for twenty years. Zen fit the way of life of the samurai : confronting death without fear, and acting in a spontaneous and intuitive way. During this period the Five Mountain System was established, which institutionalized an influential part of the Rinzai school. In the beginning of the Muromachi period the Gozan system was fully worked out. The Zen and Japanese Culture version contained five temples of both Kyoto and Kamakura. A second tier of the system consisted of Ten Temples. This system was extended throughout Japan, effectively giving control to the central government, which administered this system. Not all Rinzai Zen organisations were under such strict state control. The Rinka monasteries, which were primarily located in rural areas rather than cities, had a greater degree of independence. After a period of war Japan was re-united in the Azuchi—Momoyama period. -

Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan

Soto Zen in Medieval Japan Kuroda Institute Studies in East Asian Buddhism Studies in Ch ’an and Hua-yen Robert M. Gimello and Peter N. Gregory Dogen Studies William R. LaFleur The Northern School and the Formation of Early Ch ’an Buddhism John R. McRae Traditions of Meditation in Chinese Buddhism Peter N. Gregory Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought Peter N. Gregory Buddhist Hermeneutics Donald S. Lopez, Jr. Paths to Liberation: The Marga and Its Transformations in Buddhist Thought Robert E. Buswell, Jr., and Robert M. Gimello Studies in East Asian Buddhism $ Soto Zen in Medieval Japan William M. Bodiford A Kuroda Institute Book University of Hawaii Press • Honolulu © 1993 Kuroda Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 93 94 95 96 97 98 5 4 3 2 1 The Kuroda Institute for the Study of Buddhism and Human Values is a nonprofit, educational corporation, founded in 1976. One of its primary objectives is to promote scholarship on the historical, philosophical, and cultural ramifications of Buddhism. In association with the University of Hawaii Press, the Institute also publishes Classics in East Asian Buddhism, a series devoted to the translation of significant texts in the East Asian Buddhist tradition. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bodiford, William M. 1955- Sotd Zen in medieval Japan / William M. Bodiford. p. cm.—(Studies in East Asian Buddhism ; 8) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8248-1482-7 l.Sotoshu—History. I. Title. II. Series. BQ9412.6.B63 1993 294.3’927—dc20 92-37843 CIP University of Hawaii Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources Designed by Kenneth Miyamoto For B. -

Dokument in Tabellen

Der wichtige Punkt besteht darin, das Ver- Debate : Zen und Krieg halten in jener Zeit zu untersuchen und zu (Der Präsident) verstehen, und vor allem, davon ausge- hend unsere eigene Praxis von hier und Als Antwort auf das Buch «Zen, Nationa- jetzt tief zu betrachten. lismus und Krieg» von Brian Victoria und auf die Anschuldigungen, am Zweiten Worauf müssen wir achten, damit solche Weltkrieg teilgenommen und ihn unter- Entgleisungen weder im Grossen noch im stützt zu haben, die darin gegen das japa- Kleinen je wieder geschehen? Was müssen nische Zen, einschliesslich Kodo Sawaki, wir in unserer Praxis und Unterweisung vorgebracht werden, eröffnen wir hiermit entwickeln, worauf müssen wir unsere eine Debatte zu diesem Thema. Aufmerksamkeit lenken, damit solche Irr- tümer sich nicht wieder ereignen? Es geht nicht darum, den Standpunkt des Zen fünfzig Jahre nach diesen Ereignissen anzugreifen oder zu verteidigen – das hal- Die Personen, die hier ihre Meinung äu- ten wir für nicht sehr nützlich. ssern, tun dies in ihrem eigenen Namen. Um nicht das Kind mit dem Bade gen kennen. Ich war selbst Soldat während auszuschütten des Russisch-Japanischen Krieges, und ich habe hart auf dem Schlachtfeld gekämpft. (von Roland Rech) Aber da wir das, was wir gewonnen haben, wieder verloren, sehe ich, dass das, was wir 1. Selbst wenn Zazen die Erweckung ist, so machten, nutzlos war. Es gibt absolut keine ist diese Verwirklichung weder andauernd Notwendigkeit dafür, Krieg zu führen.„ noch endgültig. Es ist unsere Aufgabe, unse- re falschen Vorstellungen ständig zu durch- Schliesslich Seite 21: „ Ob der Krieg gross leuchten, wie auch immer unsere Position oder klein ist, die Wurzel dafür ist in unserem und unsere Funktion in der Sangha ist. -

What Is Buddha Nature?

Vol. 7 No. 2 March/April 2006 2548 BE Water Wheel Being one with all Buddhas, I turn the water wheel of compassion. —Gate of Sweet Nectar What is Buddha Nature? By Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao to us humans. A pine tree, a chair, a dog—these have no Our study of the fundamental aspects of Zen practice problem being pine begins with an exploration of buddha-nature. In the Sho- tree, chair, and dog bogenzo fascicle “Bussho,” Dogen Zenji writes: respectively. Only human beings are All sentient beings without exception have the Buddha under the false illu- nature. The Tathagata abides forever without change. sion of a permanent, fixed “I” or ego, or small self. We are so deeply attached Let us examine the first line, which is often expounded to “me-myself” that it seems impossible to even consider in the Mahayana sutras. This statement points directly to that this is an illusion to be seen through as universal the essential nature of this very life that we are now living. whole-being. It is our task to understand this nature, to experience it directly for ourselves, and to live it in our daily lives. Have the. Although this translation uses the words “have the,” Dogen Zenji says that it is more to the point All sentient beings. We can distinguish between human to say “are.” All beings are buddha-nature. You, the pine, the beings, sentient beings, and whole-being. The word rocks, the dog, already are complete, whole, perfect as is. “sentient” means “responsive to sensations,” so it includes Buddha-nature is not something that you have, or can humans, plants, and animals. -

Prajñatara: Bodhidharma's Master

Summer 2008 Volume 16, Number 2 Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Women Acquiring the Essence Buddhist Women Ancestors: Hymn to the Perfection of Wisdom Female Founders of Tibetan Buddhist Practices Invocation to the Great Wise Women The Wonderful Benefits of a H. H. the 14th Dalai Lama and Speakers at the First International Congress on Buddhist Women’s Role in the Sangha Female Lineage Invocation WOMEN ACQUIRING THE ESSENCE An Ordinary and Sincere Amitbha Reciter: Ms. Jin-Mei Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao Chen-Lai On July 10, 1998, I invited the women of our Sangha to gather to explore the practice and lineage of women. Prajñatara: Bodhidharma’s Here are a few thoughts that helped get us started. Master Several years ago while I was visiting ZCLA [Zen Center of Los Angeles], Nyogen Sensei asked In Memory of Bhiksuni Tian Yi (1924-1980) of Taiwan me to give a talk about my experiences as a woman in practice. I had never talked about this before. During the talk, a young woman in the zendo began to cry. Every now and then I would glance her One Worldwide Nettwork: way and wonder what was happening: Had she lost a child? Ended a relationship? She cried and A Report cried. I wondered what was triggering these unstoppable tears? The following day Nyogen Sensei mentioned to me that she was still crying, and he had gently Newsline asked her if she could tell him why. “It just had not occurred to me,” she said, “that a woman could be a Buddha.” A few years later when I met her again, the emotions of that moment suddenly surfaced. -

The Story of Maezumi Roshi and His American Lineage

SUBSCRIBE OUR MAGAZINES TEACHINGS LIFE HOW TO MEDITATE NEWS ABOUT US MORE + White Plums and Lizard Tails: The story of Maezumi Roshi and his American Lineage BY NOA JONES| MARCH 1, 2004 The story of a great Zen teacher— Taizan Maezumi Roshi—and his dharma heirs. Finding innovative ways to express their late teacher’s inspiration, the White Plum sangha is one of the most vital in Western Buddhism. Photo by Big Mind Zen Center. Spring is blossom season in Japan. Drifts of petals like snow decorate the parks and streets. On May 15, 1995, in this season of renewal, venerable Zen master Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi Roshi wrote an inka poem bestowing final approval on his senior disciple, Tetsugen Glassman Sensei, the “eldest son” of the White Plum sangha, placed it in an envelope and https://www.lionsroar.com/white-plums-and-lizard-tails-the-story-of-maezumi-roshi-and-his-american-lineage/ 2/5/19, 1013 PM Page 1 of 16 gave it to his brothers. Hours later, before dawn broke over the trees of Tokyo, Maezumi Roshi drowned. His death shocked his successors, students, wife and children, and the Zen community at large. At age 64, he was head of one of the most vital lineages of Zen in America; he was seemingly healthy, fresh from retreat, invigorated by his work and focused on practice. Recently elected a Bishop, he was at the zenith of his sometimes rocky relationship with the Japanese Soto sect. But before he’d barely started, he was gone. Senior students scrambled for tickets and flew from points around the world to attend the cremation in Tokyo.