The Pennsylvania State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heterosexism Within Educational Institutions

HETEROSEXISM WITHIN EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS: COPING EFFORTS OF LESBIAN, GAY, AND BISEXUAL STUDENTS IN WEST TEXAS by VIRGINIA J. MAHAN, B.A., M.Sp.Ed. A DISSERTATION IN EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial FulfiUment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Approved December, 1998 /, Ac f3 7^? z^ ^.3 1 A/^ ^ l'^ C'S Copyright 1998, Virginia J. Mahan ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I particularly wish to thank the nine members of the Steering Committee of the Lambda Social Network who served on my advisory panel and offered comments on the first draft of Chapter IV, as well as other external reviewers: Gene Dockins, Lawrence Holbrooks, M. M., Dorinda Ann Ruiz, Virginia, and other anonymous readers. I am grateful to my committee members, Mary Tallent Runnels, Camille DeBell, and Richard Powell, for their support and valuable assistance. My appreciation goes to Terry Ann Andersen, Kathy Lewallen and the rest of the library staff at South Plains College for their assistance, as well as to Fred Logan and Kaaren Mahan for running innumerable errands. I am also grateful to Texas Tech University which provided partial support for this study through a 1998 Summer Research Scholarship Award. Pivotal to this dissertation, of course, are the 14 lesbian and gay college and university students who told their sometimes painful tales so that educators might hear, learn, and know what it is like to be a gay student in Texas. I will forever hear the echoes of their voices. Lastly, thanks to Victor Shea for his courageous letter to the editor and to whom this dissertation is dedicated. -

Police Week Dents Friday Graduating This Year with a Total of 759 Degrees / Certification Events to Raise Money, Awards

Happy Mother’s Day! Sumter Item employees share some of their favorite photos of motherhood. - A2 SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 SUNDAY, MAY 12, 2019 $1.75 Sumter to observe National 634 CCTC grads receive surprise Central Carolina Technical College honored 634 stu- Police Week dents Friday graduating this year with a total of 759 degrees / certification Events to raise money, awards. Two ceremonies were held at Sumter County Civic Center. As icing on the honor fallen officers cake, the college formally BY DANNY KELLY recognized a mascot — the [email protected] Central Carolina Technical College Titan. Officials said Next week is National Police Week, and Sumter the mascot will help the County is participating in the annual event with college in its marketing and several events of its own. branding efforts. “Each one of the Police Week activi- PHOTOS BY BRUCE MILLS / ties (in the past) has been greatly sup- THE SUMTER ITEM ported by the community,” Sumter County Sheriff Anthony Dennis said. “I think that shows, especially here in Sumter County, that there is a good relationship between law enforce- DENNIS ment and the community.” National Police Week started in 1962 when President John F. Kennedy signed a proclamation designating the week of May 15 as Peace Officers Memorial Day, which is now known as National Police Week, to honor those who have given their lives in the line of duty. To kick off National Police Week, Sumter Police Department and Sumter County Sheriff’s Office will hold the 2019 National Police Week Golf Tour- nament at the Links at Lakewood on Monday, May 13. -

America and the Musical Unconscious E Music a L Unconl S Cious

G Other titles from Atropos Press Music occupies a peculiar role in the field of American Studies. It is undoubtedly (EDS.) “It is not as simple as saying that music REVE/P JULIUS GREVE & SASCHA PÖHLMANN Resonance: Philosophy for Sonic Art recognized as an important form of cultural production, yet the field continues does this or that; exploring the musical On Becoming-Music: to privilege textual and visual forms of art as its objects of examination. The es- unconscious means acknowledging the Between Boredom and Ecstasy says collected in this volume seek to adjust this imbalance by placing music cen- very fact that music always does more.” ter stage while still acknowledging its connections to the fields of literary and Philosophy of Media Sounds ÖHLMANN Hospitality in the Age of visual studies that engage with the specifically American cultural landscape. In Media Representation doing so, they proffer the concept of the ‘musical unconscious’ as an analytical tool of understanding the complexities of the musical production of meanings in various social, political, and technological contexts, in reference to country, www.atropospress.com queer punk, jazz, pop, black metal, film music, blues, carnival music, Muzak, hip-hop, experimental electronic music, protest and campaign songs, minimal ( E music, and of course the kazoo. DS. ) Contributions by Hanjo Berressem, Christian Broecking, Martin Butler, Christof Decker, Mario Dunkel, Benedikt Feiten, Paola Ferrero, Jürgen AMERIC Grandt, Julius Greve, Christian Hänggi, Jan Niklas Jansen, Thoren Opitz, Sascha Pöhlmann, Arthur Sabatini, Christian Schmidt, Björn Sonnenberg- Schrank, Gunter Süß, and Katharina Wiedlack. A A ND TH AMERICA AND THE MUSICAL UNCONSCIOUS E MUSIC A L UNCON S CIOUS ATROPOS PRESS new york • dresden 5 6 4 7 3 8 2 9 1 10 0 11 AMERICA AND THE MUSICAL UNCONSCIOUS JULIUS GREVE & SASCHA PÖHLMANN (EDS.) America and the Musical Unconscious Copyright © 2015 by Julius Greve and Sascha Pöhlmann (Eds.) The rights of the contributions remain with the respective authors. -

Roads to Zion Hip Hop’S Search for the City Yet to Come

5 Roads to Zion Hip Hop’s Search for the City Yet to Come No place to live in, no Zion See that’s forbidden, we fryin’ —Kendrick Lamar, “Heaven and Hell” (2010) The sense of the end-times and last days must be entered in order to find the creative imagination that can reveal paths of survival and threads of renewal as chaos winds its wicked way back to cosmos again. —Michael Meade Robin D. G. Kelley, in his book Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, argues that Exodus served as the key political and moral compass for African Americans during the antebellum era and after the Civil War.1 Exodus gave people a critical language for understanding the racist state they lived in and how to build a new nation. Exodus signified new beginnings, black self-determination, and black autonomy. Marcus Garvey’s “Back to Africa” movement represented a pow- erful manifestation of this vision of Exodus to Zion. He even purchased the Black Star shipping line in order to transport goods and people back to their African motherlands. Though Garvey’s Black Star Line made only a few voyages, it has remained a powerful symbol of the longing for home. As the dream of Exodus faded, Zion has become the more central metaphor of freedom and homecoming in contemporary black cultural expressions. Along these lines, Emily Raboteau—reggae head and daughter of the re- nowned historian of African American religion Albert J. Raboteau—explores Zion as a place that black people have yearned to be in her book, Searching for Zion: The Quest for Home in the African Diaspora.2 In her wanderings through Jamaica, Ethiopia, Ghana, and the American South and her conversations with Rastafarians and African Hebrew Israelites, Evangelicals, Ethiopian Jews, and Ka- trina transplants, one truth emerges: there are many roads to Zion. -

The Lantern Vol. 61, No. 2, Summer 1994 Thomar Devine Ursinus College

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College The Lantern Literary Magazines Ursinusiana Collection Summer 1994 The Lantern Vol. 61, No. 2, Summer 1994 Thomar Devine Ursinus College Laura Devlin Ursinus College Elaine Tucker Ursinus College Chris Bowers Ursinus College Sonny Regelman Ursinus College See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/lantern Part of the Fiction Commons, Illustration Commons, Nonfiction Commons, and the Poetry Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Devine, Thomar; Devlin, Laura; Tucker, Elaine; Bowers, Chris; Regelman, Sonny; Ruth, Torre; Gorman, Erin; Simpson, Willie; Cosgrove, Ellen; Stead, Richard; Rawls, Annette; Maynard, Jim; Mead, Heather; Rubin, Harley David; Faucher, Craig; Sabol, Kristen; Bano, Kraig; Zerbe, Angie; Vigliano, Jennifer; Smith, Alexis; Lumi, Carrie; Schapira, Christopher; Kais, Jim; Woll, Fred; Deussing, Chris; and McCarthy, Dennis Cormac, "The Lantern Vol. 61, No. 2, Summer 1994" (1994). The Lantern Literary Magazines. 144. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/lantern/144 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Ursinusiana Collection at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Lantern Literary Magazines by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Thomar Devine, Laura Devlin, Elaine Tucker, Chris Bowers, Sonny Regelman, Torre Ruth, Erin Gorman, Willie Simpson, Ellen Cosgrove, Richard Stead, Annette Rawls, Jim Maynard, Heather Mead, Harley David Rubin, Craig Faucher, Kristen Sabol, Kraig Bano, Angie Zerbe, Jennifer Vigliano, Alexis Smith, Carrie Lumi, Christopher Schapira, Jim Kais, Fred Woll, Chris Deussing, and Dennis Cormac McCarthy This book is available at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/lantern/144 Vol. -

Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music Thomas Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2884 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ANALYZING GENRE IN POST-MILLENNIAL POPULAR MUSIC by THOMAS JOHNSON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 THOMAS JOHNSON All rights reserved ii Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music by Thomas Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________ ____________________________________ Date Eliot Bates Chair of Examining Committee ___________________ ____________________________________ Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Mark Spicer, advisor Chadwick Jenkins, first reader Eliot Bates Eric Drott THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Analyzing Genre in Post-Millennial Popular Music by Thomas Johnson Advisor: Mark Spicer This dissertation approaches the broad concept of musical classification by asking a simple if ill-defined question: “what is genre in post-millennial popular music?” Alternatively covert or conspicuous, the issue of genre infects music, writings, and discussions of many stripes, and has become especially relevant with the rise of ubiquitous access to a huge range of musics since the fin du millénaire. -

The Road to Civil Rights Table of Contents

The Road to Civil Rights Table of Contents Introduction Dred Scott vs. Sandford Underground Railroad Introducing Jim Crow The League of American Wheelmen Marshall “Major” Taylor Plessy v. Ferguson William A. Grant Woodrow Wilson The Black Migration Pullman Porters The International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters The Davis-Bacon Act Adapting Transportation to Jim Crow The 1941 March on Washington World War II – The Alaska Highway World War II – The Red Ball Express The Family Vacation Journey of Reconciliation President Harry S. Truman and Civil Rights South of Freedom Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Too Tired to Move When Rulings Don’t Count Boynton v. Virginia (1960) Freedom Riders Completing the Freedom Ride A Night of Fear Justice in Jackson Waiting for the ICC The ICC Ruling End of a Transition Year Getting to the March on Washington The Civil Rights Act of 1964 The Voting Rights March The Pettus Bridge Across the Bridge The Voting Rights Act of 1965 March Against Fear The Poor People’s Campaign Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Completing the Poor People’s Campaign Bureau of Public Roads – Transition Disadvantaged Business Enterprises Rodney E. Slater – Beyond the Dreams References 1 The Road to Civil Rights By Richard F. Weingroff Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, "Wait." But when . you take a cross country drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you . then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. -

Individual Dog Records at Group Level

GROUP JUDGING: 1986-2017 DATA: SHO-YR = CKC SHOW NUMBER #B =NUMBER OF DOGS AT BREED LEVEL #GR=NUMBER OF DOGS AT GROUP LEVEL #SHO=NUMBER OF DOGS IN SHOW P = GROUP PLACEMENT (1-4; 0=NONE) BIS=BEST IN SHOW (1=BIS; 0=NONE) NDD=NUMBER OF DOGS DEFEATED DOG: Bullseye's Whimsical Traveller (L.Gordon) SHO- YR #B #GR #SHO P BIS NDD JUDGE 1- 86 3 18 364 0 0 2 Miss A.R.Clark (Greenwood, DE) 2- 86 3 20 431 4 0 11 Mr.R.W.Taylor (Franklin Center,PQ) 3- 86 3 21 413 0 0 2 Mr.N.Aubrey-Jones (Montreal,PQ) 60- 86 5 30 305 4 0 16 Mr.N.Aubrey-Jones (Montreal,PQ) 61- 86 4 28 294 2 0 25 Mrs.A.Mackie (Calgary,AB) 371- 86 1 41 339 0 0 0 Mrs.V.Hampton (Doylestown,PA) 373- 86 2 34 306 0 0 1 Mr.F.Young (Burbank,CA) 558- 86 2 16 351 0 0 1 Mr.E.Grieve (Calgary,AB) 559- 86 2 14 382 0 0 1 Mr.M.Riddle (Ravenna,OH) 560- 86 2 14 332 4 0 7 Mrs.L.Riddle (Ravenna,OH) 640- 86 1 34 520 0 0 0 Miss M.MacBeth (Stouffville,ON) 641- 86 2 38 634 0 0 1 Mr.M.Vandekinder (Delta,BC) 642- 86 3 35 626 0 0 2 Mrs.A.Mackie (Calgary,AB) 20- 87 2 15 266 0 0 1 Mrs.P.Wolfish (Toronto,ON) 21- 87 3 23 344 0 0 2 Mr.J.C.Ross (Saskatoon,Sask) 22- 87 2 21 338 0 0 1 Mrs.S.Diamond (Kirkland,PQ) 109- 87 4 25 482 0 0 3 Dr.D.C.Fitzsimmons (Ottawa,ON) 110- 87 8 32 627 0 0 7 Mr.A.Warnock (London,ON) 111- 87 9 34 576 0 0 8 Mr.J.Kilgannon (Edmonton,AB) 361- 87 3 24 262 0 0 2 Mr.A.Garland (Moncton,NB) 362- 87 3 24 283 4 0 11 Dr.S.Morrow-Francis (Toronto,ON) 431- 87 1 14 238 0 0 0 Mr.R.W.Taylor (Franklin Center,PQ) 432- 87 1 20 290 0 0 0 Mr.L.Rogers (Langley,BC) 433- 87 1 12 274 0 0 0 Mr.L.Stanbridge (Troy,ON) -

Holy Cow Longhorns Spotlight Genetics

P 1 P 2 Holy Cow Longhorns Spotlight Genetics M usic Adelita HCL DOB 04/04/2016 Music Man BCB X HL Dode’s Adelita Foundation Cow in the Making! Exposed to Top Shelf BCB DOB 05/28/2016 Bandera Chex X Tingaling BCB E scondido Diva HCL DOB 10/20/2016 RR Escondido Red 260 X RR Sweet Diva Horn Genetics! Sire—RR Escondido Red 260 84” TTT X 113” TH at Four Years Old CONSIGNORS John Marshall Tyson Leonard Ron Skinner Blue Ridge Ranch Leonard Farms R and R Ranch Llano, TX Galax, VA Cypress, TX BlueRidgelLonghorns.com LeonardLonghornFarms.com RRLonghorns.com Lot #H1, H32, 1, 29, 72, 73 Lot #H11, H24, 9 Lotpea #H25, 12 Stan & Jimmie Jernigan Mikeal Beck Mike Beijl Rocky Oaks Holy cow Longhorns MB Longhorns Cross Plains, TX Weatherford, TX Denton, TX Lot #H2, H9, H21, 11, 71 HolyLowlonghorns.com MBLonghorns.com Lot #H12, H22 Lot #H26, 22 Randall & Cindy Traywick El Dorado Ranch Longhorns Joe & Stephanie Sedlacek Jeremy & Tina Johnson Round Mountain, TX Lazy J Longhorns Rancho Dos Ninos ElDoradoRanchLonghorns.com Greenleaf, KS San Antonio, TX Lot #H3 LazyJLonghorns.com DosNinosRanch.com Lot #H13, 13, 63 Lot #H27 Kurt & Glenda Twining Silver T Ranch Larry & Toni Stegemoller Trey Whichard Dallas, TX TL Longhorns 4W Ranch SilverTRanch.com Cleburne, TX Sugar Land, TX Lot #H4, 7, 30 TLTexasLonghorns.com FourWRanch.com Lot #H14 Lot #H30, 3, 20, 67 John and Christy Randolph Lonesome Pines Ranch Mike Casey Ethan & Ashely Loos Smithville, TX Fairlea Longhorn Ranch, LLC Wolfridge Ranch LonesomePinesRanch.com Nicasio, CA Columbus, IL Lot# H5, H17, H29, 32 FairleaLonghorns.com -

Group Judging: 1986-2017 Data: Sho-Yr = Ckc Show Number

GROUP JUDGING: 1986-2017 DATA: SHO-YR = CKC SHOW NUMBER #B =NUMBER OF DOGS AT BREED LEVEL #GR=NUMBER OF DOGS AT GROUP LEVEL #SHO=NUMBER OF DOGS IN SHOW P = GROUP PLACEMENT (1-4; 0=NONE) BIS=BEST IN SHOW (1=BIS; 0=NONE) NDD=NUMBER OF DOGS DEFEATED JUDGE: Mrs.Sally Bremner (Surrey,BC) SHO- YR #B #GR #SHO P BIS NDD DOG 74- 86 2 27 253 0 0 1 Kilcullen's End Of The Rainbow (M.Guinn) 95- 86 2 31 334 3 0 24 Wheatlee's Blarney Kaitlyn (F.Talbot) 331- 86 2 16 221 0 0 1 Westland's Feldhund Angie (F.Zimmerman) 459- 86 2 14 191 0 0 1 Windcrest's Killarney Chorus (S.Monroe & D.Green) 435- 87 5 21 263 4 0 16 Holweit's Sunflower (S.& W.Hamilton) 464- 87 1 34 469 1 0 33 Holweit's Sunflower (S.& W.Hamilton) 604- 87 2 30 433 4 0 20 Broussepoil Bougainvilla (E.Summers & L.Moffett- Lockquell) 80- 88 5 27 224 0 0 4 Waggish Starfire (M.Stewardson) 388- 88 1 42 363 0 0 0 Blarney's Elderberry (D.& W.Hamilton) 456- 88 1 13 105 4 0 4 Waggish Starlite Star Brite (G.& B.McNeil) 96- 89 1 7 86 1 0 6 Waggish Starlite Star Brite (G.& B.McNeil) 336- 89 1 10 112 3 0 6 Golden Star's Irish Blessing CD (P.Tims) 526- 89 7 41 539 0 0 6 Holweit's Forget Me Not (S.& W.Hamilton & N.Faircloth) 546- 89 4 40 381 0 0 3 Golden Star's Irish Blessing CD (P.Tims) 598- 89 6 43 403 0 0 5 Hion New Rave (J.Hodgkins) 112- 90 7 35 336 2 0 32 Waggish Starfire (M.Stewardson) 390- 90 1 18 245 0 0 0 Clover's Ever So Softly (L.Nadeau & R.Remple) 484- 90 8 18 186 1 0 17 Waggish Starfire (M.Stewardson) 621- 90 5 45 448 2 0 43 Hion New Rave (J.Hodgkins) 409- 91 1 21 269 1 0 20 Brenmoor's Alpha Romeo -

1200055720 Dissertation Todd

“I Wouldn’t Want to Be Anyone Else”: Disabled Girlhood and Post-ADA Structures of Feeling by Anastasia Todd A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved November 2016 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Heather Switzer, Co-Chair Mary Margaret Fonow, Co-Chair Julia Himberg ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2016 ABSTRACT Spotlighting the figure of the exceptional disabled girl as she circulates in the contemporary mediascape, this dissertation traces how this figure shapes the contours of a post-Americans with Disabilities Act structure of feeling. I contend that the figure of the exceptional disabled girl operates as a reparative future girl. As a reparative figure, she is deployed as a sign of the triumph of U.S. benevolence, as well as a stand-in for the continuing fantasy and potential of the promise of the American dream, or the good life. Affectively managing the fraying of the good life through a shoring up of ablenationalism, the figure of the exceptional disabled girl rehabilitates the nation from a place of ignorance to understanding, from a place of nervous anxiety to one of hopeful promise, and from a precarious present to a not-so-bleak-looking future. Placing feminist cultural studies theories of affect in conversation with feminist disability studies and girlhood studies, this dissertation maps evocations of disabled girlhood. It traces how certain affective states as an intersubjective glue stick to specific disabled girls’ bodies and how these intersubjective attachments generate an emergent affective atmosphere that attempts to repair the fraying fantasy of the good life. -

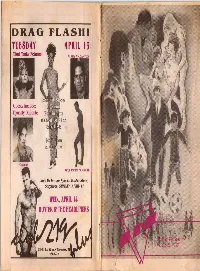

E• Ft a Cr FLASK TUESDAY J APRIL 13

E• Ft A cr FLASK TUESDAY j APRIL 13 Mimi Marks Returns Mr. Gay WI-USA - Todd Guests Include: to sent! Dynasty Duponte L01111 ilio:ftict Greg (former Mr. Gay WI) Join Us for our Special Easter Show, Surprises. SUNDAY, APRIL I I WED., APRIL 14 HUNTER & THE HEADLINERS 219 S. 2nd Street • Milwaukee. WI 271-3732 --\` 3 In Step `• April 8-21, 8-21,1993 1993 • ` Page Page 22 Cover Story 777eThe Gay Gay SideS/.de cartoonist cartoonist Tom + :-= I Rezza retilrnsreturns with another piece forfor the cover, done in heavy pastels. ThisThis isis TomesToms version of "Family"Family Values" within the LesbiBiGay community. We also thought itit 225 S. 2nd2nd St. v• Milwaukee, WIWl 53204 53204 would be be appropriateappropriate asas we approach the Phone:Plione: (414)278-7840(414)278-7840 T• Fax:Fax: 278-5868278-5868 ' March onon Washington,Washington, slated for April 2525 ISSNlssN ## 1045-24351045-2435 where the diversitydiversity ofof our our communftycommunity willwill be obvious to all. By By the the way, way, coverage coverage ofof thethe Publisher/Editor March beginsbegins on page four of the IvewsNews Ron Geiman NewsNeus CrewCrew JamakayaTcljffJamakaya•Cliff O'Neillv O'Neill•Rex Rex Wockner Columnists/Contributors \M^/\MN Wells III.lllTDennis Dennis MCMillahTTonyMcMillan•Tony TerryTeny Arnie Malmon•YvonneMalmon TYvonne Zipter•Shelly Zipterv shelly RobertsRoberts Robert BrezsnyvBrersny • EldonEldon Murray Deadline Note Publisher's AideAide de CampCamp Joe KochKoch • Deadline Deadline National Ad RepresentativesRepresentatives for thethe next issue East: Rivet`dellRivendell Marketing Covering April 2222-Ivlay-May 5, 5,1993 1993 (908) 769-8850769-8850 Isls 7pm, Wednesday, AprilApril 14 14 WestWest: a.k.a.