Democratizing Communication: Media Activism and Broadcasting Reform in Thailand Monwipa Wongrujira

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand White Paper

THE BANGKOK MASSACRES: A CALL FOR ACCOUNTABILITY ―A White Paper by Amsterdam & Peroff LLP EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For four years, the people of Thailand have been the victims of a systematic and unrelenting assault on their most fundamental right — the right to self-determination through genuine elections based on the will of the people. The assault against democracy was launched with the planning and execution of a military coup d’état in 2006. In collaboration with members of the Privy Council, Thai military generals overthrew the popularly elected, democratic government of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, whose Thai Rak Thai party had won three consecutive national elections in 2001, 2005 and 2006. The 2006 military coup marked the beginning of an attempt to restore the hegemony of Thailand’s old moneyed elites, military generals, high-ranking civil servants, and royal advisors (the “Establishment”) through the annihilation of an electoral force that had come to present a major, historical challenge to their power. The regime put in place by the coup hijacked the institutions of government, dissolved Thai Rak Thai and banned its leaders from political participation for five years. When the successor to Thai Rak Thai managed to win the next national election in late 2007, an ad hoc court consisting of judges hand-picked by the coup-makers dissolved that party as well, allowing Abhisit Vejjajiva’s rise to the Prime Minister’s office. Abhisit’s administration, however, has since been forced to impose an array of repressive measures to maintain its illegitimate grip and quash the democratic movement that sprung up as a reaction to the 2006 military coup as well as the 2008 “judicial coups.” Among other things, the government blocked some 50,000 web sites, shut down the opposition’s satellite television station, and incarcerated a record number of people under Thailand’s infamous lèse-majesté legislation and the equally draconian Computer Crimes Act. -

The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics by Zachary Abuza

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 6 The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics by Zachary Abuza Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Complex Operations, and Center for Strategic Conferencing. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, and publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Thai and U.S. Army Soldiers participate in Cobra Gold 2006, a combined annual joint training exercise involving the United States, Thailand, Japan, Singapore, and Indonesia. Photo by Efren Lopez, U.S. Air Force The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand: Trends in Violence, Counterinsurgency Operations, and the Impact of National Politics By Zachary Abuza Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 6 Series Editors: C. Nicholas Rostow and Phillip C. Saunders National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. -

243 the Ongoing Conflict in Southern Thailand and Its

243 THE ONGOING CONFLICT IN SOUTHERN THAILAND AND ITS INTERNATIONAL IMPLICATIONS BAJUNID, Omar Farouk JAPONYA/JAPAN/ЯПОНИЯ ABSTRACT The military coup that was launched on September 19, 2006 in Thailand to bring down the government of Thaksin Shinawatra for its alleged failure to resolve the on-going crisis of confidence in the Thai capital as well as the escalating political violence in the deep south, demonstrated in no uncertain terms that Thai democracy itself was in crisis. The fact that the political quagmire in Thailand’s southernmost periphery was affecting the power configuration at the centre in Bangkok is also unprecedented. Probably, this is one reason why there is no shortage of attempts to try to analyse what has gone wrong in Thailand and its southernmost region. As the southernmost part of Thailand, comprising the provinces of Pattani, Yala, Narathiwat and to a lesser extent, Songkhla and Satun, are overwhelmingly Malay and Islamic, departing from the the rest of Thailand which is distinctively Thai in respect of culture and Buddhist in terms of religion, the politics of ethnicity is assumed to be the principal cause of the problem. However, no matter how the problem is analysed, what seems to emerge is that the on-going conflict in Southern Thailand is actually a function of a complex interplay of factors. This paper intends to focus on the nature and dimensions of the unresolved conflict in Southern Thailand and its actual and prospective international implications. It begins by re-capitulating the different ways in which the problem has been viewed before exploring the various external factors that have contributed to its persistence. -

Digital Convergence in the Newsroom

DIGITAL CONVERGENCE IN THE NEWSROOM: EXAMINING CROSS -MEDIA NEWS PRODUCTION AND QUALITY JOURNALISM By SAKULSRI SRISARACAM SUPERVISOR: STUART ALLAN SECOND SUPERVISOR: JOANNA REDDEN A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Cardiff University School of Journalism, Media and Culture June 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my great appreciation, first and foremost, for my supervisor, Professor Stuart Allan. I am greatly honored to work with you because you always give me encouragement, support, advice and patience in helping me finishing this piece of academic work. You were never too busy to give advice and every discussion always broadens my understanding and knowledge. You have shown me by example what a true te acher should be: supportive and inspiring, which help me balancing my workload and academic research goals. I also wish to thank my second supervisor, Dr Joanna Redden , for your advice to sharpen my thesis and helpful encouragement. I thank my family , esp ecially my husband , who have supported me through everything, constantly proving your love and commitment. I owe my successful completion of this research to my husband’s selfless contribution to take care of our son and give me time to concentrate on my s tudy with understanding and encouragement. I have felt many emotions, through happy and difficult times but because of you, I have never felt alone. Thank s to my parents for constant support and giv ing me courage to fulfil my goal. I thank to my universit y for part ial financial support and the opportunity to take months off from teaching to be able to complete this research. -

ኄʼࡓ˗ڎúˌᄪҭˁઆᠫ͘ the 3 China-ASEAN Business And

úˌᄪҬˁઆᠫ͘ڎ˗ኄʼࡓ The 3rd China-ASEAN Business and Investment Summit ࠒᮗ̡ڎѣࣞन࣫रᄊ State Leaders at the Opening Ceremony ࠧᯫᄱ ӿएࡉ᜵̎ፒ Ꮵေۥေ ᖈᔚ˝ ಌڎ˗ ພࠒࠃ ֻጪ࠷eӰ࠷۳̎ᬐʾ ห೨ ᔚ᜵ว ฉ H. E. Wen Jiabao His Majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal H. E. Samdech Hun Sen H. E. Susilo Bambang H. E. Bouasone Premier of China Bolkiah, Sultan and Yang Di- Prime Minister Yudhoyono, President of Bouphavanh Pertuan of Brunei of Cambodia Indonesia Prime Minister of Laos ေ ᡕӯေڎေ ฑڹᯱ᜵̎ေ ፵ႅေ ᖧ॥ࠖፒ ழҫ ࣅ፥ ພ ᬁᎭጞ ౄ௭ᴝ ጉઢᐲ ௰һ H. E. Abdullah bin Haji H. E. Soe Win Madame Gloria Macapagal- H. E. Lee Hsien Loong H. E. Surayud Chulanont H. E. Nguyen Tan Dung Ahmad Badawi Prime Minister of Arroyo, President of the Prime Minister of Prime Minister of Prime Minister of Prime Minister of Malaysia Myanmar Philippines Singapore Thailand Vietnam ᒱൔᤁᣯᮗ न࣫र˟ે̡ Leader Giving Welcome Remarks Chair of the Opening Ceremony úˌᄪҬˁઆᠫ͘ڎ˗ ᝮnj˺ނᒭӝЗீܥࣹ᜵ڎ˗ ᬅڎڎ˗͘˟͊njނ͘˟͊ ጸނ̡ܸ Ѷ݉ᗁ Ψᤉނր᫂͘͘ H. E. Liu Qibao ʺߣᮻ Secretary of the CPC Guangxi H. E. Wan Jifei Committee and Chairman of Chairman of the Organizing Guangxi People’s Congress, Committee of CABIS and CCPIT China úˌᄪҬˁઆᠫ͘˟ᮥ֗ำүڎ˗ኄʼࡓ Theme and Main Events of the 3rd CABIS NjNjᫎὉࣲథெ Time: October 31, 2006 ˟NjNjᮥὉСՏᄊᭊ᜶ἻСՏᄊళ Theme: One Need, One Future úˌᄪᒭႀӝઆ Topic 1: Improving Investment Environment and Stimulatingڎ˗ἻүܒᮥʷὉஈؓઆᠫဗ˄ Two-way Flow of Investment within the CAFTA ᠫᄊԥՔืү Topic 2: Construction of the CAFTA —Opportunity and Challenge úˌᄪᒭႀӝथúú᥅ˁ્੍ڎ˗ᮥ̄Ὁ˄ Main Events: dž Opening Ceremony ˟ᮥำүὉdžन࣫र dž Dialogue with State Leaders I džᮗ̡˄ᮥࠫភʷ -

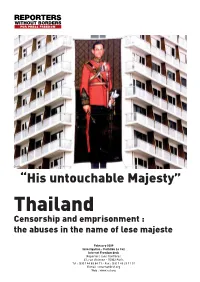

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development. -

The Democracy Monument: Ideology, Identity, and Power Manifested in Built Forms อนสาวรุ ยี ประชาธ์ ปไตยิ : อดมการณุ ์ เอกลกษณั ์ และอำนาจ สอผ่ื านงานสถาป่ ตยกรรมั

The Democracy Monument: Ideology, Identity, and Power Manifested in Built Forms อนสาวรุ ยี ประชาธ์ ปไตยิ : อดมการณุ ์ เอกลกษณั ์ และอำนาจ สอผ่ื านงานสถาป่ ตยกรรมั Assistant Professor Koompong Noobanjong, Ph.D. ผชู้ วยศาสตราจารย่ ์ ดร. คมพงศุ้ ์ หนบรรจงู Faculty of Industrial Education, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology, Ladkrabang คณะครุศาสตร์อุตสาหกรรม สถาบันเทคโนโลยีพระจอมเกล้าเจ้าคุณทหารลาดกระบัง Abstract This research article examines the methods of power mediation in the design of the Democracy Monument in Bangkok, Thailand. It examines its underlying concept and mechanisms for conveying political power and social practice, along with the national and cultural identity that operates under an ideological framework. The study consists of two major parts. First, it investigates the monument as a political form of architecture: a symbolic device for the state to manifest, legitimize, and maintain power. The focus then shifts to an architectural form of politics: the ways in which ordinary citizens re-appropriated the Democracy Monument through semantic subversions to perform their social and political activities as well as to form their modern identities. Via the discourse theory, the analytical and critical discussions further reveal complexity, incongruity, and contradiction of meanings in the design of the monument in addition to paradoxical relationships with its setting, Rajadamnoen Avenue, which resulted from changes in the country’s socio-political situations. บทคดยั อ่ งานวิจัยชิ้นนี้ศึกษากระบวนการสื่อผ่านอำนาจอนุสาวรีย์ประชาธิปไตย -

November 6, 2020 Thai Enquirer Summary Political News • the Wait

November 6, 2020 Thai Enquirer Summary Political News The wait to see the next US President seems to be getting closer as nearly 98 per cent of the vote count in the state of Georgia and just over 95 per cent on the state of Pennsylvania. Although this morning incumbent President Donald Trump came out to hold a press conference at 06:30 am (Thai time) that the ongoing counting of the votes is ‘illegal’. On the domestic politics, it seems that embattled Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha has come out to accept his fate for the 1st time During a talk yesterday Prayut came out to say that it was not his choice to be there and that he ‘would be happy to have someone more capable and honest than me’ take over his position and that he was tired of using his authority. This comes as Parliament Speaker – Chuan Leekpai, continues to talk to hold talks with various former Prime Ministers (except Thaksin & Yingluck Shinawatra and not to mention Suchinda Kraprayoon). Chuan said he will travel to meet former prime minister and privy councillor Gen Surayud Chulanont in person to invite him to join the panel. When asked about other former prime ministers like Thanin Kraiwichien, Chuan said he may ask Thanin but that depends on Thanin’s health. The Parliament President also plans to approach other senior figures like former House speakers. Following Phalang Pracharat Party (PPRP) MP Sira Jenjaka’s comment that the reconciliation panel should shun senior citizens, Chuan said he had phoned those senior figures referred to by Sira. -

A Coup Ordained? Thailand's Prospects for Stability

A Coup Ordained? Thailand’s Prospects for Stability Asia Report N°263 | 3 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Thailand in Turmoil ......................................................................................................... 2 A. Power and Legitimacy ................................................................................................ 2 B. Contours of Conflict ................................................................................................... 4 C. Troubled State ............................................................................................................ 6 III. Path to the Coup ............................................................................................................... 9 A. Revival of Anti-Thaksin Coalition ............................................................................. 9 B. Engineering a Political Vacuum ................................................................................ 12 IV. Military in Control ............................................................................................................ 16 A. Seizing Power -

Aalborg Universitet from Thaksin's Social Capitalism to Self-Sufficiency

Aalborg Universitet From Thaksin's Social Capitalism to Self-sufficiency Economics in Thailand Schmidt, Johannes Dragsbæk Publication date: 2007 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Schmidt, J. D. (2007). From Thaksin's Social Capitalism to Self-sufficiency Economics in Thailand. Paper presented at Autochthoneity or Development? Asian ‘Tigers' in the World: Ten Years after the Crisis, Wien, Austria. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: September 27, 2021 From Thaksin=s Social Capitalism to Self-sufficiency Economics in Thailand1 Johannes Dragsbaek Schmidt2 Introduction More than a decade after the financial crash, which turned into a social crisis, Thailand has now entered a new phase of political instability. 19 September 2006, with Prime Minister Thaksin out of the country, a faction of Thailand's military led by General Sonthi Boonyaratglin staged the 18th military coup in the history of the country, suspended the constitution, and declared martial law. -

Civil Society in Thailand

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. An Analysis of the Role of Civil Society in Building Peace in Ethno-religious Conflict: A Case Study of the Three Southernmost Provinces of Thailand A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and Public Policy at The University of Waikato by KAYANEE CHOR BOONPUNTH 2015 ii Abstract The ‘Southern Fire’ is an ethno-religious conflict in the southernmost region of Thailand that has claimed thousands of innocent lives since an upsurge in violence in 2004. Although it does not catch the world’s attention as much as other conflict cases in the same region, daily violent incidents are ongoing for more than a decade. The violence in the south has multiple causes including historical concerns, economic marginalisation, political and social issues, religious and cultural differences, educational opportunity inequities, and judicial discrimination. -

Ethnic Separatism in Southern Thailand: Kingdom Fraying at the Edge?

1 ETHNIC SEPARATISM IN SOUTHERN THAILAND: KINGDOM FRAYING AT THE EDGE? Ian Storey Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies March 2007 The Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies (APCSS) is a regional study, conference and research center under the United States Department of Defense. The views in this paper are personal opinions of the author, and are not official positions of the U.S. government, the U.S. Pacific Command, or the APCSS. All APCSS publications are posted on the APCSS web site at www.apcss.org. Overview • Since January 2004 separatist violence in Thailand’s three Muslim-majority southern provinces has claimed the lives of nearly 1,900 people. • The root causes of this latest phase of separatist violence are a complex mix of history, ethnicity, and religion, fueled by socio-economic disparities, poor governance, and political grievances. Observers differ on the role of radical Islam in the south, though the general consensus is that transnational terrorist groups are not involved. • A clear picture of the insurgency is rendered difficult by the multiplicity of actors, and by the fact that none of the groups involved has articulated clear demands. What is apparent, however, is that the overall aim of the insurgents is the establishment of an independent Islamic state comprising the three provinces. • The heavy-handed and deeply flawed policies of the Thaksin government during 2004-2006 deepened the trust deficit between Malay-Muslims and the Thai authorities and fueled separatist sentiment. 2 • Post-coup, the Thai authorities have made resolving violence in the south a priority, and promised to improve governance and conduct a more effective counter-insurgency campaign.