UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“L.A. Raw” RADICAL CALIFORNIA by Patricia Cronin

“L.A. Raw” hris Burden Donatello, 1975 RADICAL CALIFORNIA private collection by Patricia Cronin Maverick independent curator Michael Duncan has mounted a visceral, hair-raising survey exhibition of figurative art by more than 40 Los Angeles artists in “L.A. RAW: Abject Expressionism in Los Angeles 1945-1980, from Rico LeBrun to Paul McCarthy,” Jan. 22-May 20, 2012, at the Pasadena Museum of California Art. The show is a revelatory part of the Getty Initia- Nancy Buchanan tive’s 60-exhibition extravaganza “Pacific Standard Time,” whose various Wolfwoman, 1977 events have been reviewed prolifically byArtnet Magazine’s own Hunter courtesy of the artist and Drohojowska-Philp. Cardwell Jimmerson Contemporary Art In Los Angeles, artists responded to post-war existential questions in a dramatically different fashion than their East Coast counterparts. While the New York School turned to Abstract Expressionism (simultaneously shift- ing the epicenter of the art world from Paris and Europe), artists in L.A. fashioned a much more direct and populist response to the realities of the Vietnam war, the horrors of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, and the threat of McCarthyism. The hallmark of this kind of work is the expressively distort- ed human body, constitutig a new, distinctly West Coast kind of human- ism. Of the 41 artists in the show, ten percent had fled Europe and immigrated to the U.S., and nearly half of them, including the occult performance art- Rico Lebrun The Oppressor (after de Sade, 6–8) ist Marjorie Cameron (1922-1995), served in the Armed Forces in WWII. 1962 Ben Sakoguchi was sent to a wartime internment camp when he was only courtesy of Koplin Del Rio Gallery, four years old, and Kim Jones served in Vietnam. -

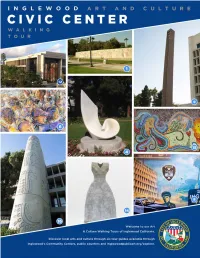

Civic-Center-Final-Web-081621.Pdf

The History of Transportation Helen Lundeberg, Artist 1940, Petromosaic mural 230 S. Grevillea Ave., Inglewood, CA 90301 The History of Transportation by Helen Lundeberg shows the history of human transportation in the Centinela Valley, including Inglewood. The mural, comprised of 60 panels with crushed rock set in mortar, showcases technological changes in transportation from walking to horses and carts, to railroads and propeller-driven airplanes. A playful small white dog appears throughout the artwork’s 240’ length. The History of Transportation was a commission from the Federal Works Progress Administration, and is the largest mural in that program. The mural was originally built along one of Inglewood’s most traveled commuter arteries. After auto incidents destroyed two of the sixty panels, a multifaceted, four-year conservation effort began. The mural was re-installed in 2009 on city property specially landscaped as Grevillea Art Park. It faces Inglewood High School and is perpendicular to the bustling Manchester Boulevard. The relocation was led by Landscape Architect Randall Meyer and Associates with restoration and interpretive kiosks by Sculpture Conservation Studios in partnership with the Feitelson/Lundeberg Art Foundation. Inglewood War Memorial Designer unknown 1970, Monument City Hall, 1 W. Manchester Blvd., Inglewood, CA 90301 The Inglewood War Memorial is sited on the green expanses fronting City Hall’s Manchester Boulevard entrance. The memorial is comprised of a marble obelisk on a granite base before a flag court. The center panel on the granite base holds the words: “To keep forever living the freedom for which they died. We dedicate this memorial to our dead in World War II, Korea and Vietnam.” Service veteran’s names are on the plinth. -

The Written Word (1972)

THE WRITTEN WORD (1972) The Written Word is Tom Van Sant’s public art treatment for three distinct con- Artist: crete areas of the Inglewood Public Library. The work is cast into the concrete Tom Van Sant surfaces of the exterior stairwell column on Manchester; the lower level of an interior lobby, and an exterior wall of the Lecture Hall. Collection: City of Inglewood Van Sant explores the development of written thought in numbers, letters, Medium: theories and histories from diverse cultures in diverse times. Egyptian hiero- Bas-Relief glyphics, Polynesian counting systems, European cave painting and Einstein’s mathematical equations are some of the many images to inspire Library’s Material: patrons with the wealth of words found inside. Poured-in-place concrete Van Sant was commissioned through the NEA Art in Architecture program to work with Civic Center architects Charles Luckman and Associates, This artwork required special molds built in reverse so the texts and drawings would be cor- rectly read, a technique requiring a high degree of craft. The Written Word is one of the few examples of a poured-in-place concrete bas-relief in the Los Angeles basin and one of the largest to employ this technique in the world. Inglewood Public Library 101 West Manchester Boulevard Inglewood, CA INGLEWOOD PUBLIC ART EDUCATION PROJECT 1 Tom Van Sant Tom Van Sant is a sculptor, painter, and conceptual artist with major sculpture and mural commissions for public spaces around the world. His art is collected globally. His professional skills and interests include archi- tecture, planning, education, an advanced technical invention. -

CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING and SCULPTURE 1969 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Js'i----».--:R'f--=

Arch, :'>f^- *."r7| M'i'^ •'^^ .'it'/^''^.:^*" ^' ;'.'>•'- c^. CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING AND SCULPTURE 1969 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign jS'i----».--:r'f--= 'ik':J^^^^ Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture 1969 Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture DAVID DODD5 HENRY President of the University JACK W. PELTASON Chancellor of the University of Illinois, Urbano-Champaign ALLEN S. WELLER Dean of the College of Fine and Applied Arts Director of Krannert Art Museum JURY OF SELECTION Allen S. Weller, Chairman Frank E. Gunter James R. Shipley MUSEUM STAFF Allen S. Weller, Director Muriel B. Christlson, Associate Director Lois S. Frazee, Registrar Marie M. Cenkner, Graduate Assistant Kenneth C. Garber, Graduate Assistant Deborah A. Jones, Graduate Assistant Suzanne S. Stromberg, Graduate Assistant James O. Sowers, Preparator James L. Ducey, Assistant Preparator Mary B. DeLong, Secretary Tamasine L. Wiley, Secretary Catalogue and cover design: Raymond Perlman © 1969 by tha Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Library of Congress Catalog Card No. A48-340 Cloth: 252 00000 5 Paper: 252 00001 3 Acknowledgments h.r\ ^. f -r^Xo The College of Fine and Applied Arts and Esther-Robles Gallery, Los Angeles, Royal Marks Gallery, New York, New York California the Krannert Art Museum are grateful to Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, Inc., New those who have lent paintings and sculp- Fairweother Hardin Gallery, Chicago, York, New York ture to this exhibition and acknowledge Illinois Dr. Thomas A. Mathews, Washington, the of the artists, Richard Gallery, Illinois cooperation following Feigen Chicago, D.C. collectors, museums, and galleries: Richard Feigen Gallery, New York, Midtown Galleries, New York, New York New York ACA Golleries, New York, New York Mr. -

AAR Magazine Spring Summer 2021`

AMERICAN ACADEMY IN ROME MAGAZINE SPRING/ SUMMER 2021 A Message from the Chair of the Board of Trustees It’s hard to believe it’s been over a year since the world paused. Thank you for your continued com- mitment to AAR in what I’m sure we will remember as one of society’s most challenging moments. Your time, expertise, guidance, and financial support have all been instrumental in seeing the Academy through this period. I’d also like to thank Mark Robbins and the whole team, especially those on the ground in Rome, for their incredible dedication to navigating the ups, downs, and surprises this past year has brought. Turning to today, the Academy has successfully reopened and the selection process for next year’s fellowship class is complete. AAR is in a much stronger position than I could have imagined when the full pandemic crisis became clear in March 2020. Our finances are stable and (with vaccinations) we believe that by the fall our activities will be close to fully restored. One of the many downsides of this past year has been the lack of direct connection, and we look for- ward to future gatherings in person, here and in Rome. With appreciation and gratitude, Cary Davis Chair, AAR Board of Trustees SPRING/SUMMER 2021 UP FRONT FEATURES 2 20 LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT SEEING THE ANCIENT WORLD AAR receives major gift of photographs 4 by Carole Raddato FAR AFIELD Checking in with past Fellows and Residents 24 GIVING FOR THE AGES 6 Richard E. Spear and Athena Tacha INTRODUCING underwrite a new Rome Prize The 2020–2021 Rome Prize winners -

Cultural Arts Commission Meeting Englewood, CO 80110 Wednesday, March 4, 2020 ♦ 5:45 PM

1000 Englewood Pkwy – Englewood Public AGENDA Library Perrin Room Cultural Arts Commission Meeting Englewood, CO 80110 Wednesday, March 4, 2020 ♦ 5:45 PM 1. Chair Carroll approved the agenda on 2/26/2020 2. Call to Order 3. Roll Call 4. Approval of Minutes February 5, 2020 Cultural Arts Commission - 05 Feb 2020 - Minutes - Pdf 5. Scheduled Public Comment (presentation limited to 10 minutes) 6. Unscheduled Public Comment (presentation limited to 5 minutes) Pacific Coast Conservation - Samantha Hunt-Durán PCC_Firm Profile Public Art 7. New Business 8. Old Business Strategic Plan Initiatives 1) Initiative #1 Creative Crosswalks a) Application 2) Initiative #2 Conservation of Public Art 3) Initiative #8 Swedish Horse s Project Update 4) Cultural Arts Survey Update 5) Initiative #6 Pop-up Concerts 2020 Englewood Crosswalk Application 9. Upcoming Events 10. Staff's Choice 11. Commissioner's Choice 12. Adjournment Please note: If you have a disability and need auxiliary aids or services, please notify the City of Englewood (303-762-2405) at least 48 hours in advance of when services are needed. Page 1 of 10 Draft MINUTES Cultural Arts Commission Meeting Wednesday, February 5, 2020 PRESENT: Clarice Ambler Laura Bernero Martin Gilmore Mark Hessling Leabeth Pohl Cheryl Wink Tim Vacca, Museum of Outdoor Arts Courtenay Cotton, Guest ABSENT: David Carroll Brenda Hubka STAFF PRESENT: Christina Underhill, Director of Parks, Recreation and Library Jon Solomon, Library Manager Michelle Brandstetter, Adult Services Librarian Madeline Hinkfuss, Community Resource Coordinator Debby Severa, Staff Liaison 1. Call to Order a. Vice Chair Pohl called the meeting to order at 5:44pm. -

RICHARD CALLNER American Artist (1927-2007)

RICHARD CALLNER American Artist (1927-2007) EDUCATION University of Wisconsin, Madison. BFA. 1946-1948 Acadêmie Julian, Paris. Certificate. 1948-1949 Columbia University, New York. MFA. 1952 SELECTED ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2003 Richard Callner: A Fifty-Year Retrospective. Albany Institute of History and Art. Albany, New York. 1997 Richard Callner: Exhibition of Paintings, Watercolor, Gouache, Oil, Art Gallery, Snowden Library. Lycoming College, Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Richard Callner. Hyde Collection. Glens Falls, New York 1997 Richard Callner, A Retrospective Exhibition, Bertha V.B. Lederer Gallery State University of New York College of Geneseo, Geneseo, New York. 1995 Richard Callner ’95: Oils and Watercolors, Concordia College Art Gallery, Bronxville, New York. 1994 Richard Callner: Small Works, Paintings and Drawings, Russell Sage College Art Gallery, Troy, New York. 1990 Richard Callner: Selected Works, Haenah-Kent Gallery, New York, New York. 1988 Richard Callner: Selected Works 1951-1988, (Retrospective) University Art Museum, University at Albany. (catalog). 1984 Alpha Gallery, Split, Yugoslavia. 1984 Atrium Gallery, General Electric Corporate Research and Development Center, Schenectady, New York. 1980 Cork Arts Society, County Cork, Ireland. 1977 Richard Callner’s Lilith. University Art Galleries. SUNY Albany. 1975 Bristol Museum, Bristol, Rhode Island. 1974 National Academy of Science, Washington, D. C. 1970 Ten Year Retrospective (1960-1970), Tyler School of Art, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1964 Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana. 1963 Ten Year Retrospective (1953-1963), Chatham College, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 1960 Eight Year Retrospective (1952-1960), Milwaukee Jewish Cultural Center, Milwaukee, Wisconsin SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 1997 The Contemporary Landscape, Philip and Muriel Berman Museum of Art. Ursinus College, Collegeville, Pennsylvania. 1997 Drawings, The Pelham Arts Center, Pelham, New York 1997 Memory and Mourning, University Art Museum, University at Albany. -

Incomplete Conch Shell (1972)

INCOMPLETE CONCH SHELL (1972) Jack Zajac draws inspiration from the natural world in his marble sculpture Artist: titled Incomplete Conch Shell. Blending traditions of surrealist and romanticist Jack Zajac art, Incomplete Conch Shell bisects the marine shell’s central chamber with blunt geometry. The form is displayed on a circular pedestal on the west lawn Collection: of the Civic Center. Organic and abstract, the curvaceous work sits in strong City of Inglewood contrast to the geometric architecture of City Hall. Material: White Carrera marble Incomplete Conch Shell was purchased for the newly opened Inglewood Civic Center with funds made available through the Art in Architecture program of the National Endowment for the Arts. Inglewood Civic Center 1 West Manchester Boulevard Inglewood, CA INGLEWOOD PUBLIC ART EDUCATION PROJECT 1 Photo on the right was taken shortly after installation. It is from the Inglewood Public Library Collection. Jack Zajac Jack Zajac is an artist renown for his bronze and marble sculpture. His work is in museum collections at the Hirshhorn, MOMA, San Jose Museum of Art, the Walker Art Center and many other public and private collections. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Rome Prize and has been honored with solo exhibits and recognition. Born in 1929 in Ohio, Zajac’s family moved to California when he was fifteen. He credits early work at Kaiser Steel Mill to enable him to attend Scripps College and explore the world of art. Living and travelling internationally, Zajac cur- rently resides in central California. INGLEWOOD PUBLIC ART EDUCATION PROJECT 2. -

1 Santa Barbara Museum of Art Archives 1130 State Street Santa

Santa Barbara Museum of Art Archives 1130 State Street Santa Barbara, CA 93101 Finding Aid to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art Publications Collections, 1941 – ongoing Collection number: ARCH.PUB.001 Finding Aid written by: Mackenzie Kelly Completed: 2018 ©2018 Santa Barbara Museum of Art. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Collection Summary……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 3 Information for Researchers…………………………………………………………………………p. 4 Administrative Information…………………………………………………………………………..p. 5 Scope and Content…………………………………………………………………………………..…..p. 6 Series Description…………………………………………………………………………………………p. 7 Container List……………………………………………………………………………………………….p. 8 – 31 Series 1.1: Exhibition Catalogues and Brochures, 1941 – Ongoing………………..p. 8 – 29 Series 1.2: Exhibition Ephemera, 1953 Ongoing……………………………………………p. 29 – 30 Series 2: Other Publications, 1953 – Ongoing……………………………………………….p. 30 Series 3: Newsletters, 1943 – Ongoing………………………………………………………….p. 30 – 31 Series 4: Annual Reports, 1940 – 2006………………………………………………………….p. 31 2 Collection Summary Collection Title Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Publications Collection, 1941 – ongoing Collection Number ARCH.PUB.001 Creator Santa Barbara Museum of Art Extent 25 linear feet (boxes, oversize, tubes, etc.) Repository Santa Barbara Museum of Art Archives 1130 State Street Santa Barbara, CA 93101 Abstract The Santa Barbara Museum of Art Publication collection documents the Museum’s publications from 1941 to the present. The collection includes exhibition catalogues, brochures, invitations, newsletters, -

Paintings by Streeter Blair (January 12–February 7)

1960 Paintings by Streeter Blair (January 12–February 7) A publisher and an antique dealer for most of his life, Streeter Blair (1888–1966) began painting at the age of 61 in 1949. Blair became quite successful in a short amount of time with numerous exhibitions across the United States and Europe, including several one-man shows as early as 1951. He sought to recapture “those social and business customs which ended when motor cars became common in 1912, changing the life of America’s activities” in his artwork. He believed future generations should have a chance to visually examine a period in the United States before drastic technological change. This exhibition displayed twenty-one of his paintings and was well received by the public. Three of his paintings, the Eisenhower Farm loaned by Mr. & Mrs. George Walker, Bread Basket loaned by Mr. Peter Walker, and Highland Farm loaned by Miss Helen Moore, were sold during the exhibition. [Newsletter, memo, various letters] The Private World of Pablo Picasso (January 15–February 7) A notable exhibition of paintings, drawings, and graphics by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), accompanied by photographs of Picasso by Life photographer David Douglas Duncan (1916– 2018). Over thirty pieces were exhibited dating from 1900 to 1956 representing Picasso’s Lautrec, Cubist, Classic, and Guernica periods. These pieces supplemented the 181 Duncan photographs, shown through the arrangement of the American Federation of Art. The selected photographs were from the book of the same title by Duncan and were the first ever taken of Picasso in his home and studio. -

III Bienal Do Museu De Arte Moderna De São Paulo 1955

HÁ M E lOS É C U L O fornece artigos poro desenho pintura engenharia São Paulo - Ruo Libero Badaró, 1 18 F o n e s 3 2 - 2 2 9 2 -- 3 5 - 4 2 5 7 FALCHI Chocolates Caramelos Bombons um céu aberto ... com os luxuosos Super DC·68 da Aff'=I1fAff'=IA de sio PAULO p! Usboa, Milão • Romo às 30s. feiros. p/ Buenos Aires às 2.s. I.iro, Par. maiores inform'fócs, consulte sua Agencia Je Viagens ou os Agentes Gerais para o Brasil -=-....=...~..".~ ----===-- 22 21 _~~:«;:.'i,. " .---------:." --. ~ ~, 20 19 18 17 16 ~ Andar superior: 9, Estados Unidos; 10, França; 11, Itália; 12, Holanda; 13, Grã-Bretanha (Sutherlandl; 14, sala especial Taeu berarp e sala geral Suíça; 15, Noruéga; de 16 a 21: Antilhas Holandêsas, Bolívia, Canadá, Chile, Cuba, Grão Ducado de Luxemburgo, Grécia, Israel, Iugoslávia, Ja pão, México, Nicarágua, Paquistão, Paraguai, Portugal, República Dominicana, União Panamericana, Uruguai, Venezuela, Viet-Nam. I 3 2 l ~ I I Andar térreo: 1, sala especial Portinari; 2 e 3, sala geral Brasil; 4, sala especial Sega"; 5, sala especial Beckmann; 6, sala geral Alemanha; 7, sala geral Áustria e salas especiais Thôny e Kubin; 8, Bélgica. ......... .... ... -.~. --.. _~- ~-----. 9 ID ~. --_._------ -,---- - --~------ . --------~ .. ._,-,,--- - --~---_.. : 13: E E E =12 l'l . __ • - _u _ ._______ ~_ __0' _._'n _._. ___ .~_'_ ~~ I 81 ,/.~/> I 1 I I l < 6 ~/~. C 14 1 . 1 r 1 j' 5 , I I I I I I I EXECUÇÃO DA VIDROTlL - Vidrotil Indústria e Comércio de Vidros Ltda. -

A Finding Aid to the Downtown Gallery Records,1824-1974, Bulk 1926-1969, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Downtown Gallery Records,1824-1974, bulk 1926-1969, in the Archives of American Art Catherine Stover Gaines Funding for the processing, microfilming and digitization of the microfilm of this collection was provided by the Henry Luce Foundation. Glass plate negatives in this collection were digitized in 2019 with funding provided by the Smithsonian Women's Committee. 2000 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 8 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 9 Appendix B: Chronological List of Downtown Gallery Exhibitions................................. 10 Names and Subjects .................................................................................................... 25 Container Listing ........................................................................................................... 28