American Sculpture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“L.A. Raw” RADICAL CALIFORNIA by Patricia Cronin

“L.A. Raw” hris Burden Donatello, 1975 RADICAL CALIFORNIA private collection by Patricia Cronin Maverick independent curator Michael Duncan has mounted a visceral, hair-raising survey exhibition of figurative art by more than 40 Los Angeles artists in “L.A. RAW: Abject Expressionism in Los Angeles 1945-1980, from Rico LeBrun to Paul McCarthy,” Jan. 22-May 20, 2012, at the Pasadena Museum of California Art. The show is a revelatory part of the Getty Initia- Nancy Buchanan tive’s 60-exhibition extravaganza “Pacific Standard Time,” whose various Wolfwoman, 1977 events have been reviewed prolifically byArtnet Magazine’s own Hunter courtesy of the artist and Drohojowska-Philp. Cardwell Jimmerson Contemporary Art In Los Angeles, artists responded to post-war existential questions in a dramatically different fashion than their East Coast counterparts. While the New York School turned to Abstract Expressionism (simultaneously shift- ing the epicenter of the art world from Paris and Europe), artists in L.A. fashioned a much more direct and populist response to the realities of the Vietnam war, the horrors of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, and the threat of McCarthyism. The hallmark of this kind of work is the expressively distort- ed human body, constitutig a new, distinctly West Coast kind of human- ism. Of the 41 artists in the show, ten percent had fled Europe and immigrated to the U.S., and nearly half of them, including the occult performance art- Rico Lebrun The Oppressor (after de Sade, 6–8) ist Marjorie Cameron (1922-1995), served in the Armed Forces in WWII. 1962 Ben Sakoguchi was sent to a wartime internment camp when he was only courtesy of Koplin Del Rio Gallery, four years old, and Kim Jones served in Vietnam. -

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004 Distinguished Scholars Reception Program (Date – TBD) Preface A HUNDRED YEARS OF SCHOLARSHIP AND RESEARCH AT MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY DISTINGUISHED SCHOLARS’ RECEPTION (DATE – TBD) At today’s reception we celebrate the outstanding accomplishments, excluding scholarship and creativity of Marquette remarkable records in many non-scholarly faculty, staff and alumni throughout the pursuits. It is noted that the careers of last century, and we eagerly anticipate the some alumni have been recognized more coming century. From what you read in fully over the years through various this booklet, who can imagine the scope Alumni Association awards. and importance of the work Marquette people will do during the coming hundred Given limitations, it is likely that some years? deserving individuals have been omitted and others have incomplete or incorrect In addition, this gathering honors the citations in the program listing. Apologies recipient of the Lawrence G. Haggerty are extended to anyone whose work has Faculty Award for Research Excellence, not been properly recognized; just as as well as recognizing the prestigious prize scholarship is a work always in progress, and the man for whom it is named. so is the compilation of a list like the one Presented for the first time in the year that follows. To improve the 2000, the award has come to be regarded completeness and correctness of the as a distinguishing mark of faculty listing, you are invited to submit to the excellence in research and scholarship. Graduate School the names of individuals and titles of works and honors that have This program lists much of the published been omitted or wrongly cited so that scholarship, grant awards, and major additions and changes can be made to the honors and distinctions among database. -

SEC Complaint

Case: 3:19-cv-00809 Document #: 1 Filed: 09/30/19 Page 1 of 101 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF WISCONSIN __________________________________________ ) UNITED STATES SECURITIES ) AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Case No. 19-cv-809 ) BLUEPOINT INVESTMENT COUNSEL , ) LLC, MICHAEL G. HULL, ) CHRISTOPHER J. NOHL, ) JURY DEMANDED CHRYSALIS FINANCIAL LLC, and ) GREENPOINT ASSET MANAGEMENT II ) LLC, ) ) Defendants. ) ______________________________________________________________________________ COMPLAINT Plaintiff, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”), alleges as follows: Introduction 1. Michael G. Hull (“Hull”) and his entity, Greenpoint Asset Management II LLC, and Christopher J. Nohl (“Nohl”) and his entity, Chrysalis Financial LLC, perpetrated an offering fraud. Hull and Nohl through their entities manage Greenpoint Tactical Income Fund LLC (“Greenpoint Tactical Income Fund” or the “Fund”). From April 25, 2014 to June 2019, Hull, Nohl, and their entities raised approximately $52.783 million from approximately 129 investors in 10 states. 2. Hull is also the co-owner of Bluepoint Investment Counsel, LLC (“Bluepoint”), a now de-registered investment adviser that claimed to have as much as $145 million in assets under management. Bluepoint through Hull recommended that all of Bluepoint’s individual clients 1 Case: 3:19-cv-00809 Document #: 1 Filed: 09/30/19 Page 2 of 101 invest in the Greenpoint Tactical Income Fund and other affiliated Greenpoint Funds. Hull made these recommendations without regard for each individual investor’s needs and circumstances. 3. Hull, Nohl, and their entities are investment advisers to Greenpoint Tactical Income Fund and owe fiduciary duties to the Fund including a duty of loyalty. -

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

Charles Grafly Papers

Charles Grafly Papers Collection Summary Title: Charles Grafly Papers Call Number: MS 90-02 Size: 55.0 linear feet Acquisition: Donated by Dorothy Grafly Drummond Processed by: MD, 1990; JEF, 5-19-1998; MN, 1-30-2015 Note: Related collections: MS 93-04, Dorothy Grafly Papers; MS 93-05, Leopold Sekeles Papers Restrictions: None Literary Rights Literary rights were not granted to Wichita State University. When permission is granted to examine manuscripts, it is not an authorization to publish them. Manuscripts cannot be used for publication without regard for common law literary rights, copyright laws and the laws of libel. It is the responsibility of the researcher and his/her publisher to obtain permission to publish. Scholars and students who eventually plan to have their work published are urged to make inquiry regarding overall restrictions on publication before initial research. Content Note Charles Grafly was an American sculptor whose works include monumental memorials and portrait busts. Dating from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, his correspondence relating to personal, business and other matters is collected here as well as newspaper clippings about his works, sketches and class notes, scrapbooks, photographs of his works, research materials and glass plate negatives. All file folder titles reflect the original titles of the file folders in the collection. For a detained description of the contents of each file folder, refer to the original detailed and incomplete finding aid in Box 76. Biography Born and raised in Philadelphia, Charles Grafly (1862-1929) studied under painters Thomas Eakins and Thomas Anshutz at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts between 1884-88. -

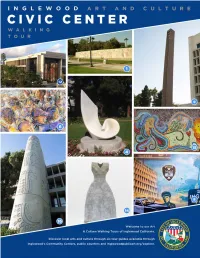

Civic-Center-Final-Web-081621.Pdf

The History of Transportation Helen Lundeberg, Artist 1940, Petromosaic mural 230 S. Grevillea Ave., Inglewood, CA 90301 The History of Transportation by Helen Lundeberg shows the history of human transportation in the Centinela Valley, including Inglewood. The mural, comprised of 60 panels with crushed rock set in mortar, showcases technological changes in transportation from walking to horses and carts, to railroads and propeller-driven airplanes. A playful small white dog appears throughout the artwork’s 240’ length. The History of Transportation was a commission from the Federal Works Progress Administration, and is the largest mural in that program. The mural was originally built along one of Inglewood’s most traveled commuter arteries. After auto incidents destroyed two of the sixty panels, a multifaceted, four-year conservation effort began. The mural was re-installed in 2009 on city property specially landscaped as Grevillea Art Park. It faces Inglewood High School and is perpendicular to the bustling Manchester Boulevard. The relocation was led by Landscape Architect Randall Meyer and Associates with restoration and interpretive kiosks by Sculpture Conservation Studios in partnership with the Feitelson/Lundeberg Art Foundation. Inglewood War Memorial Designer unknown 1970, Monument City Hall, 1 W. Manchester Blvd., Inglewood, CA 90301 The Inglewood War Memorial is sited on the green expanses fronting City Hall’s Manchester Boulevard entrance. The memorial is comprised of a marble obelisk on a granite base before a flag court. The center panel on the granite base holds the words: “To keep forever living the freedom for which they died. We dedicate this memorial to our dead in World War II, Korea and Vietnam.” Service veteran’s names are on the plinth. -

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION a Project Of

Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A project of edited by Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman Remember the Women Institute, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit corporation founded in 1997 and based in New York City, conducts and encourages research and cultural activities that contribute to including women in history. Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel is the founder and executive director. Special emphasis is on women in the context of the Holocaust and its aftermath. Through research and related activities, including this project, the stories of women—from the point of view of women—are made available to be integrated into history and collective memory. This handbook is intended to provide readers with resources for using theatre to memorialize the experiences of women during the Holocaust. Women, Theater, and the Holocaust FOURTH RESOURCE HANDBOOK / EDITION A Project of Remember the Women Institute By Rochelle G. Saidel and Karen Shulman This resource handbook is dedicated to the women whose Holocaust-related stories are known and unknown, told and untold—to those who perished and those who survived. This edition is dedicated to the memory of Nava Semel. ©2019 Remember the Women Institute First digital edition: April 2015 Second digital edition: May 2016 Third digital edition: April 2017 Fourth digital edition: May 2019 Remember the Women Institute 11 Riverside Drive Suite 3RE New York,NY 10023 rememberwomen.org Cover design: Bonnie Greenfield Table of Contents Introduction to the Fourth Edition ............................................................................... 4 By Dr. Rochelle G. Saidel, Founder and Director, Remember the Women Institute 1. Annotated Bibliographies ....................................................................................... 15 1.1. -

Class of 1965 50Th Reunion

CLASS OF 1965 50TH REUNION BENNINGTON COLLEGE Class of 1965 Abby Goldstein Arato* June Caudle Davenport Anna Coffey Harrington Catherine Posselt Bachrach Margo Baumgarten Davis Sandol Sturges Harsch Cynthia Rodriguez Badendyck Michele DeAngelis Joann Hirschorn Harte Isabella Holden Bates Liuda Dovydenas Sophia Healy Helen Eggleston Bellas Marilyn Kirshner Draper Marcia Heiman Deborah Kasin Benz Polly Burr Drinkwater Hope Norris Hendrickson Roberta Elzey Berke Bonnie Dyer-Bennet Suzanne Robertson Henroid Jill (Elizabeth) Underwood Diane Globus Edington Carol Hickler Bertrand* Wendy Erdman-Surlea Judith Henning Hoopes* Stephen Bick Timothy Caroline Tupling Evans Carla Otten Hosford Roberta Robbins Bickford Rima Gitlin Faber Inez Ingle Deborah Rubin Bluestein Joy Bacon Friedman Carole Irby Ruth Jacobs Boody Lisa (Elizabeth) Gallatin Nina Levin Jalladeau Elizabeth Boulware* Ehrenkranz Stephanie Stouffer Kahn Renee Engel Bowen* Alice Ruby Germond Lorna (Miriam) Katz-Lawson Linda Bratton Judith Hyde Gessel Jan Tupper Kearney Mary Okie Brown Lynne Coleman Gevirtz Mary Kelley Patsy Burns* Barbara Glasser Cynthia Keyworth Charles Caffall* Martha Hollins Gold* Wendy Slote Kleinbaum Donna Maxfield Chimera Joan Golden-Alexis Anne Boyd Kraig Moss Cohen Sheila Diamond Goodwin Edith Anderson Kraysler Jane McCormick Cowgill Susan Hadary Marjorie La Rowe Susan Crile Bay (Elizabeth) Hallowell Barbara Kent Lawrence Tina Croll Lynne Tishman Handler Stephanie LeVanda Lipsky 50TH REUNION CLASS OF 1965 1 Eliza Wood Livingston Deborah Rankin* Derwin Stevens* Isabella Holden Bates Caryn Levy Magid Tonia Noell Roberts Annette Adams Stuart 2 Masconomo Street Nancy Marshall Rosalind Robinson Joyce Sunila Manchester, MA 01944 978-526-1443 Carol Lee Metzger Lois Banulis Rogers Maria Taranto [email protected] Melissa Saltman Meyer* Ruth Grunzweig Roth Susan Tarlov I had heard about Bennington all my life, as my mother was in the third Dorothy Minshall Miller Gail Mayer Rubino Meredith Leavitt Teare* graduating class. -

The Written Word (1972)

THE WRITTEN WORD (1972) The Written Word is Tom Van Sant’s public art treatment for three distinct con- Artist: crete areas of the Inglewood Public Library. The work is cast into the concrete Tom Van Sant surfaces of the exterior stairwell column on Manchester; the lower level of an interior lobby, and an exterior wall of the Lecture Hall. Collection: City of Inglewood Van Sant explores the development of written thought in numbers, letters, Medium: theories and histories from diverse cultures in diverse times. Egyptian hiero- Bas-Relief glyphics, Polynesian counting systems, European cave painting and Einstein’s mathematical equations are some of the many images to inspire Library’s Material: patrons with the wealth of words found inside. Poured-in-place concrete Van Sant was commissioned through the NEA Art in Architecture program to work with Civic Center architects Charles Luckman and Associates, This artwork required special molds built in reverse so the texts and drawings would be cor- rectly read, a technique requiring a high degree of craft. The Written Word is one of the few examples of a poured-in-place concrete bas-relief in the Los Angeles basin and one of the largest to employ this technique in the world. Inglewood Public Library 101 West Manchester Boulevard Inglewood, CA INGLEWOOD PUBLIC ART EDUCATION PROJECT 1 Tom Van Sant Tom Van Sant is a sculptor, painter, and conceptual artist with major sculpture and mural commissions for public spaces around the world. His art is collected globally. His professional skills and interests include archi- tecture, planning, education, an advanced technical invention. -

CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING and SCULPTURE 1969 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Js'i----».--:R'f--=

Arch, :'>f^- *."r7| M'i'^ •'^^ .'it'/^''^.:^*" ^' ;'.'>•'- c^. CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING AND SCULPTURE 1969 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign jS'i----».--:r'f--= 'ik':J^^^^ Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture 1969 Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture DAVID DODD5 HENRY President of the University JACK W. PELTASON Chancellor of the University of Illinois, Urbano-Champaign ALLEN S. WELLER Dean of the College of Fine and Applied Arts Director of Krannert Art Museum JURY OF SELECTION Allen S. Weller, Chairman Frank E. Gunter James R. Shipley MUSEUM STAFF Allen S. Weller, Director Muriel B. Christlson, Associate Director Lois S. Frazee, Registrar Marie M. Cenkner, Graduate Assistant Kenneth C. Garber, Graduate Assistant Deborah A. Jones, Graduate Assistant Suzanne S. Stromberg, Graduate Assistant James O. Sowers, Preparator James L. Ducey, Assistant Preparator Mary B. DeLong, Secretary Tamasine L. Wiley, Secretary Catalogue and cover design: Raymond Perlman © 1969 by tha Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois Library of Congress Catalog Card No. A48-340 Cloth: 252 00000 5 Paper: 252 00001 3 Acknowledgments h.r\ ^. f -r^Xo The College of Fine and Applied Arts and Esther-Robles Gallery, Los Angeles, Royal Marks Gallery, New York, New York California the Krannert Art Museum are grateful to Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, Inc., New those who have lent paintings and sculp- Fairweother Hardin Gallery, Chicago, York, New York ture to this exhibition and acknowledge Illinois Dr. Thomas A. Mathews, Washington, the of the artists, Richard Gallery, Illinois cooperation following Feigen Chicago, D.C. collectors, museums, and galleries: Richard Feigen Gallery, New York, Midtown Galleries, New York, New York New York ACA Golleries, New York, New York Mr. -

Sculpture May, 2011 Lee Bul: Phantasmic Morphologies

Sculpture May, 2011 Lee Bul: Phantasmic Morphologies Michael Amy Who we are is determined to a considerable extent by what we are. The what includes our origins in time and place, gender, race, social status, sexual orientation, education, and political and religious convictions. Once we have this information, we believe that we know enough about a person to be able to classify and judge him or her. We have a tendency to embrace stereotypical thinking The South Korean artist Lee Bul moves away from what we know - or what we think we know. Her work examines how the mind functions by exploring some of its dreams, ideals, and utopias. Interviews with Lee over the years have shown her to be a highly sophisticated and articulate thinker, with a wide range of interests in the history of ideas. The cultures of both East and West, and science and technology. Her work argues that everything is in a state of flux, that many of the notions we accept as laws are often the product of bias and can-therefore-be corrected, and that the imagination constitutes an all-conquering power. Surrealism is an important source for Lee's ideas and images. She understands imagination's ties to cognition and knows from firsthand experience how it can free one from physical and ideological bonds, thus becoming of critical importance to survival. Lee was born in 1964 in a remote village In South Korea during the military dictatorship of Park Chung-Hee. Her political dissident parents were almost constantly on the move, which she says, "taught me certain strategies of survival. -

Days & Hours for Social Distance Walking Visitor Guidelines Lynden

53 22 D 4 21 8 48 9 38 NORTH 41 3 C 33 34 E 32 46 47 24 45 26 28 14 52 37 12 25 11 19 7 36 20 10 35 2 PARKING 40 39 50 6 5 51 15 17 27 1 44 13 30 18 G 29 16 43 23 PARKING F GARDEN 31 EXIT ENTRANCE BROWN DEER ROAD Lynden Sculpture Garden Visitor Guidelines NO CLIMBING ON SCULPTURE 2145 W. Brown Deer Rd. Do not climb on the sculptures. They are works of art, just as you would find in an indoor art Milwaukee, WI 53217 museum, and are subject to the same issues of deterioration – and they endure the vagaries of our harsh climate. Many of the works have already spent nearly half a century outdoors 414-446-8794 and are quite fragile. Please be gentle with our art. LAKES & POND There is no wading, swimming or fishing allowed in the lakes or pond. Please do not throw For virtual tours of the anything into these bodies of water. VEGETATION & WILDLIFE sculpture collection and Please do not pick our flowers, fruits, or grasses, or climb the trees. We want every visitor to be able to enjoy the same views you have experienced. Protect our wildlife: do not feed, temporary installations, chase or touch fish, ducks, geese, frogs, turtles or other wildlife. visit: lynden.tours WEATHER All visitors must come inside immediately if there is any sign of lightning. PETS Pets are not allowed in the Lynden Sculpture Garden except on designated dog days.