BOOK REVIEWS O'brien, Glen. Wesleyan-Holiness Churches In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Aggressive Christianity

JOURNAL OF AGGRESSIVE CHRISTIANITY http://www.armybarmy.com/JAC Issue 13 June - July 2001 Choice Wine Richard Munn Interview with Linda Bond The Chief Secretary - Canada & Bermuda Territory 'De-armifying' the Army Wesley Harris Democracy and The Salvation Army John Norton Siren Call of a Dangerous God Geoff Ryan From the new book "Sowing Dragons". Order your copy today. Family v. Mission Stephen Court What should come first? Home Schooling and The Salvation Army (Part II) Paul Van Buren Raising up a new generation for Christ. The Renewing of Power Samuel Logan Brengle A 'Born Again' Christian Graham Harris Is there any other kind? Temptation linked to Suffering David Poxon When we don't feel like responding as Job did. CHOICE WINE “No one pours new wine into old wineskins. If they do, the new wine will burst the skins, the wine will run out and the wineskins will be ruined. No, new wine must be poured into new wineskins.” Luke 5:36, 37 Over and over, it seems, we are drawn to pouring the sparkling new wine of the gospel into old wineskins. The old wineskins are known. They have worked before. We are comfortable with them. They are trusted friends. A new wineskin is unknown. It may not work. It is almost disloyal to use it. The gospel is predestined to stretch our inflexible structures and burst through our old wineskins. The wine of the gospel is always fermenting. It is a new wine, and - at the same time - a vintage wine. The gospel is both old and new. -

A Publication of the Salvation Army

A Publication of The Salvation Army Word & Deed Mission Statement: The purpose of the journal is to encourage and disseminate the thinking of Salvationists and other Christian colleagues on matters broadly related to the theology and ministry of The Salvation Army The journal provides a means to understand topics central to the mission of The Salvation Army inte grating the Army's theology and ministry in response to Christ's command to love God and our neighbor. Salvation Army Mission Statement: The Salvation Army, an international movement, is an evangelical part of the universal Christian Church. Its message is based on the Bible. Its ministry is motivated by the love of God. Its mission is to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ and to meet human needs in His name without discrimination. Editorial Address: Manuscripts, requests for style sheets, and other correspondence should be addressed to Major Ed Forster at The Salvation Army, National Headquarters, 615 Slaters Lane, Alexandria, VA 22314. Phone: (703) 684-5500. Fax: (703) 302-8623. Email: [email protected]. Editorial Policy: Contributions related to the mission of the journal will be encouraged, and at times there will be a general call for papers related to specific subjects. The Salvation Army is not responsible for every view which may be expressed in this journal. Manuscripts should be approximately 12-15 pages, including endnotes. Please submit the following: 1) three hard copies of the manuscript with the author's name (with rank and appointment if an officer) on the cover page only. This ensures objec tivity during the evaluation process. -

A Distance Education Program for the Salvation Army College for Officer Training

Please HONOR the copyright of these documents by not retransmitting or making any additional copies in any form (Except for private personal use). We appreciate your respectful cooperation. ___________________________ Theological Research Exchange Network (TREN) P.O. Box 30183 Portland, Oregon 97294 USA Website: www.tren.com E-mail: [email protected] Phone# 1-800-334-8736 ___________________________ ATTENTION CATALOGING LIBRARIANS TREN ID# Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) MARC Record # Digital Object Identification DOI # Ministry Focus Paper Approval Sheet This ministry focus paper entitled A DISTANCE EDUCATION PROGRAM FOR THE SALVATION COLLEGE FOR OFFICER TRAINING Written by BRIAN M. SAUNDERS and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry has been accepted by the Faculty of Fuller Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: _____________________________________ Kurt Fredrickson oDate Received: November 30, 2012 A DISTANCE EDUCATION PROGRAM FOR THE SALVATION ARMY COLLEGE FOR OFFICER TRAINING A MINISTRY FOCUS PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY BRIAN M. SAUNDERS NOVEMBER 2012 ABSTRACT A Distance Education Program for The Salvation Army College for Officer Training Brian M. Saunders Doctor of Ministry School of Theology, Fuller Theological Seminary 2012 The goal of this paper is to develop a distance education program for The Salvation Army’s USA Western Territory. The Salvation Army’s current clergy education program, a two-year residential college located in Southern California, is somewhat limited in that it excludes those who may not be able to relocate to Los Angeles. -

Salvationist 6 October 2012

SALVATIONIST ESSENTIAL READING FOR INSIDE THIS WEEK EVERYONE LINKED TO General leads anniversary celebrations THE SALVATION ARMY Ghana www.salvationarmy.org.uk/salvationist PAGE 4 6 October 2012 Heritage weekend attracts visitors No 1367 Croydon Price 60p PAGE 8 PLUS LOTS MORE! PAGES 11-13 PAPERS THE Ex-movie actor Michael Q GET YOUR PENCILS Williamson talks Q HOUSTON HAD A War Cryy about faith Page 8 READY FOR THE BIG salvationarmy.org.uk/warcry Est 1879 No 7085 FIGHTING FOR HEARTS AND SOULS 6 October 2012 20p/25c PROBLEM. SHE ALSO WHITNEY’S HAD FAITH DRAW Q NEW KA! JAM BIBLE TROUBLED STAR Q WHO TO TRUST – NEVER LOST FAITH SERIES – JESUS IN LAST writes RENÉE DAVIS POLITICIANS OR THE GOODBYEDBY POLICE? COMMAND Q JOKES AND AUDIENCES can expect to be Q FORMER dazzled by the musical movie, Sparkle, which debuted in UK cinemas yesterday (Friday 5 PUZZLES IN GIGGLE IN October). The film – which turned out to be PROSTITUTE AND Whitney Houston’s last – is set in 1960s’ Detroit and follows the life of 19-year- old Sparkle (Jordin Sparks), a young THE MIDDLE woman with big dreams to make it as a music star. DRUG ADDICT FINDS Her two sisters, Tammy and Delores, also have dreams. Tammy is convinced she deserves a bigger and better life. She has good looks and a singing voice to match, and isn’t afraid to use that to her advantage. FAITH IN CHRIST Q BACK-PAGE FUN Turn to page 3 WITH PERCY THE Q GAGA PERFUME Whitney PENGUIN IN PATCH’S Houston stars in ‘Sparkle’ TriStar Pictures MAKES SENSE PALS THIS WEEK’S QUOTES FROM THE PAPERS ALMIGHTY BRAWL ENDS CHRISTIAN FOOTBALL MATCH ATHEISTS WHO PRAY TO BE CONVERTED It is a league that prides itself on promoting peace You report… that 50 atheists have and understanding through football. -

Spiritual Formation Towards Christ Likeness in a Holiness Context

3377 Bayview Avenue TEL: Toronto, ON 416.226.6620 M2M 3S4 www.tyndale.ca UNIVERSITY Note: This Work has been made available by the authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research and may not be copied or reproduced except as permitted by the copyright laws of Canada without the written authority from the copyright owner. Bond, Linda Christene Diane. "Through the Lens of Grace: Spiritual Formation Towards Christlikeness in a Holiness Context." D. Min., Tyndale University College & Seminary, 2017. Tyndale University College and Seminary Through the Lens of Grace: Spiritual Formation towards Christlikeness in a Holiness Context A Research Portfolio Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry Tyndale Seminary by Linda Christene Diane Bond Toronto, Canada July 3, 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Linda Bond All rights reserved ABSTRACT To see life through the lens of grace is to gain a new perspective of how God shapes his children in the image of his Son. Spiritual formation is a process, a journey with God’s people, which calls for faith and participation, but all is of grace. This portfolio testifies to spiritual formation being God’s work. Though our involvement in spiritual disciplines and the nurturing of the Christian community are indispensable, they too are means of grace. The journey of spiritual formation for the individual Christian within the community of faith is explained in the writings of A.W. Tozer as well as the Model of Spiritual Formation in The Salvation Army. The goal is Christlikeness, a goal which requires adversity and suffering to deepen our faith and further our witness. -

Added Value INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS COORDINATOR and Hospital Project Leader 2 Communications Books – the Latest Must-Have Gadgets

OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2012 // ISSUE 6 [email protected] Prog A NEWS UPDATE FROM THE PROGRAMME RESOURCES DEPARTMENT AT IHQ International Schools Services 1 International Howard Dalziel School Services Added value INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS COORDINATOR AND HOSPITAL PROJECT LEADER 2 Communications Books – the latest must-have gadgets 7 Programme Resources Added value Capacity Building – An Urgent Priority he Salvation Army’s mission their lives as an example to students. is often summarised as ‘saving However, teachers cannot do it alone, and 4 Photo pages souls, growing saints and close relationships with corps officers, Projects from around serving suffering humanity’. local officers, Salvationists and community the world In order to best live out this members is invaluable. Tcalling, Salvation Army schools are often I saw a number of these schools on a 6 International Projects and placed in neglected and isolated areas, recent visit to Indonesia, where children Development Services serving minorities (who are working hard from disadvantaged backgrounds – both and International to fight discrimination and economic Muslim and Christian – receive an Emergency Services disadvantage) and educating young people education that ‘adds value’ through the An Army without borders who would otherwise be ignored by the dedication of staff and the local corps state. working together. Both worked to ensure 8 International In the United Kingdom teachers are that children learn in an environment Health Services assessed by their ability to demonstrate where relationships are fundamental to 130 Years of The ‘added value’. The aim is to show that spiritual, social and physical development. Salvation Army in India because of the quality of teaching received CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 44 a child has achieved beyond their academic potential. -

JOURNAL of AGGRESSIVE CHRISTIANITY Issue 76, December 2011 – January 2012

JOURNAL OF AGGRESSIVE CHRISTIANITY Issue 76, December 2011 – January 2012 Copyright © 2011 Journal of Aggressive Christianity Journal of Aggressive Christianity, Issue 76 , December 2011 – January 2012 2 In This Issue JOURNAL OF AGGRESSIVE CHRISTIANITY Issue 76, December 2011 – January 2012 Editorial Introduction page 3 Major Stephen Court JAC Exclusive Interview with General Linda Bond (JAC13) page 4 In Praise of Enthusiasm Page 8 Commissioner Wesley Harris Say It! Know It Do It! page 9 Captain Michael Ramsay Salvationism Still Works page 13 Officer X Love and Life in Community page 16 Captain Mark Braye The Ammonite Uprising page 19 Major Stephen Court Greed page 22 Major Danielle Strickland Pro-Life or Just Anti-Abortion-On-Demand page 24 Major Stephen Court Journal of Aggressive Christianity, Issue 76 , December 2011 – January 2012 3 Editorial Introduction by Major Stephen Court Welcome to the 76th edition of Journal of Aggressive Christianity. There is a wide range of content in this issue. We encourage you to share it widely through your networks. We start with a JAC exclusive interview with General Linda Bond. How did we score that, you ask? Well, it is from JAC13, back when the General was a Colonel. But the questions remain pertinent and some of the answers are even more interesting now that she is the international leader of The Salvation Army. Commissioner Wesley Harris writes In Praise Of Enthusiasm. In his classic style the Commissioner highlights a wonderful Salvationist trait though winsome exhortation. Captain Michael Ramsay also exhorts us, in Say It! Know It! Do It!, a breakdown of two key verses in Romans 10. -

Bible Study Discipleship Our Heritage Leadership COURSE C: BOOK #2 FALL 2015

BiBle Study Our he ritage leaderShip diScipleShip Leader’S GUIDE COURSE C: BOOK #2 FALL 2015 BOLD FOR CORPS CADETS COURSE C | BOOK #2 | FALL 2015 | 1st EDITION Published by The Salvation Army National Christian Education Department, National Headquarters EXECUTIVE EDITOR: Captain Keith Maynor EDITOR: Carolyn J.R. Bailey WRITERS: Carolyn J.R. Bailey, Cari Arias ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: Steven E. Carpenter, Jr. MULTIMEDIA: Joshua Duenke ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT: Siomara Paz COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This publication is a national document and cannot be changed without the approval of the Commissioners’ Conference. All rights reserved. No part of this curriculum may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopies, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission from The Salvation Army National Christian Education Department. This includes the scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means. For permission information write: The Salvation Army National Headquarters Christian Education Department 615 Slaters Lane Alexandria, VA 22314 All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV®. Copyright ©1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com The “NIV” and “New International Version” are trademarks registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by Biblica, Inc.™ Scripture marked MSG is taken from The Message™. Copyright 1993. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. Leadership principles taken from The Maxwell Leadership Bible: Lessons in Leadership from the Word of God, Second Edition, New King James Version. -

A Publication of the Salvation Army

A Publication of The Salvation Army Word & Deed Mission Statement: The purpose of the journal is to encourage and disseminate the thinking of Salvationists and other Christian colleagues on matters broadly related to the theology and ministry ofThe Salvation Army. The journal provides a means to understand topics central to the mission of The Salvation Army, inte grating the Army's theology and ministry in response to Christ's command to love God and our neighbor. Salvation Army Mission Statement: The Salvation Army, an international movement, is an evangelical part of the universal Christian Church. Its message is based on the Bible. Its ministry is motivated by the love of God. Its mission is to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ and to meet human needs in His name without discrimination. Editorial Address: Manuscripts, requests for style sheets, and other correspondence should be addressed to Major Ed Forster at The Salvation Army, National Headquarters, 615 Slaters Lane, Alexandria, VA 22314. Phone: (703) 684-5500. Fax: (703) 302-8623. Email: [email protected]. Editorial Policy: Contributions related to the mission of the journal will be encouraged, and at times there will be a general call for papers related to specific subjects. The Salvation Army is not responsible for every view which may be expressed in this journal. Manuscripts should be approximately 12-15 pages, including endnotes. Please submit the following: 1) three hard copies of the manuscript with the author's name (with rank and appointment if an officer) on the cover page only. This ensures objec tivity during the evaluation process. -

The Salvation Army and the Social Gospel: Reconciling Evangelical Intent and Social Concern

The Salvation Army and the Social Gospel: Reconciling evangelical intent and social concern Jason Davies-Kildea Dip.Miss., B.Theol., M.Theol., M.Soc.Sci A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Monash University in 2017 2 Copyright notice © Jason Davies-Kildea (2017). I certify that I have made all reasonable efforts to secure copyright permissions for third- party content included in this thesis and have not knowingly added copyright content to my work without the owner's permission. 3 Abstract The Salvation Army is one of the best-known community organisations in Australia and is highly respected for its service to those in need – at the frontlines of natural disasters, housing the homeless and lending a helping hand to struggling families. What is less well known to those outside the movement is that The Salvation Army is a Christian church. Unlike the general public, the members of this church, who are called Salvationists, see their primary purpose through the lens of evangelical Christianity. All Salvationists are involved in church activities but only a much smaller proportion take part in the Army’s social work. A series of interviews with Salvation Army officers undertaken for this research revealed that the organisation’s evangelical and social service arms often appear to be engaged in intraorganisational contestation, competition and conflict. Because some of the driving influences of conflict are related to wider social changes, such as increasing secularisation, they can also be seen to impact upon other churches and faith-based organisations. As their congregations diminish in size and number and their social service agencies continue to expand, many Australian churches are raising questions about organisational identity and mission. -

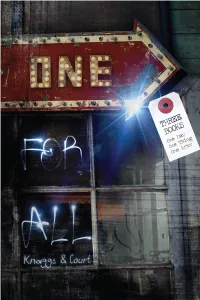

Oneforall.Pdf

ONE FOR ALL James Knaggs & Stephen Court Three books in one volume. Contents include the global editions of One Day and One Thing and the first printing of One Army. ONE DAY: “It will breathe fresh heart into Salvationists everywhere.” – General Paul Rader (Ret.) ONE THING: “There is a coherent, unassailable answer to today’s pluralism.” – General Eva Burrows (Ret.) ONE ARMY: “This book makes the case for the whole world.” – General Linda Bond i ONE FOR ALL James Knaggs and Stephen Court 2011: Frontier Press All rights reserved. Except for fair dealing permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any means without permission in writing from author/publisher. Knaggs, James (James Merle), 1950- . Court, Stephen (Stephen Ernest), 1966-. ONE FOR ALL ISBN 978-0-9768465-2-9 Scripture quotations marked (NLT) are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright 1996. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Wheaton, Illinois 60189. All rights reserved. Subediting: The Salvation Army Australian National Editorial Depart- ment and Barry Gittins Set in Adobe Garamond Pro and Girard Slab Design, typesetting and cover by [email protected] The Salvation Army USA Western Territory ii A DREAM FOR THE SALVATION ARMY GLOBAL EDITION James Knaggs & Stephen Court Applauding the first edition The vision set out in this short publication vibrates with spiritual life and holy ambition. May it become a reality more and more as the days go by and as Salvationists in every part of the world continue to seek the will of God. Let the prayers of all Salvationists uphold those working to achieve every aspect of the vision. -

One Army - on Fire One Mission - of Love One Message - of Grace

Founder From the Editor William Booth General Linda Bond Territorial Commander recently attended homes, at school or in the community or Commissioner W. Langa a Global our circle of friends. International Headquarters ILeadership 101 Queen Victoria Street, Summit, as I am sure Lt Colonel Donaldson shares with us the London EC4P 4GP England some of you did this good and bad principles of Saul’s Territorial Headquarters year as well. Every leadership and how that affected how he 119 - 121 Rissik Street, year the challenge is made decisions - note when people Johannesburg 2001 to lead better, up, with started losing. integrity, like Jesus Editor and so forth. This year We also want to honour student Officers Captain Wendy Clack Bill Hybels reminded conference goers: in our Territory that have sacrificed and Editorial Office “Everyone wins when the leader gets completed courses. Captain Colleen P.O. Box 1018 better”. Huke took time to share how we can start Johannesburg 2000 or continue to commit to life-long Tel:. (011) 718-6700 So how would the people around us win, learning. Fax: (011) 718-6790 if you and I got better at leading? Certainly we see such challenges in Jesus is certainly the greatest example of E-mail: leadership in news releases and other leadership from a historical, scientific, [email protected] print media that show us why we even medical, educational and humanitarian www.salvationarmy.org.za have a generation of people that is point of view, John Ortberg shares in his Design, Print & described as lost. They are certainly not book “Who is this Man?” What if Distribution winning.