The Consequences of Ideas: a (Prospective) Life of Richard Weaver Jay Langdale the “Legitimate Function of Modern Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Thoreau, from Which He Would Obtain Plutarch Materials Plus Quotes from Crates of Thebes and Simonides’S “Epigram on Anacreon” That He Would Recycle in a WEEK.)

HDT WHAT? INDEX 1814 1814 EVENTS OF 1813 General Events of 1814 SPRING JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH SUMMER APRIL MAY JUNE FALL JULY AUGUST SEPTEMBER WINTER OCTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER Following the death of Jesus Christ there was a period of readjustment that lasted for approximately one million years. –Kurt Vonnegut, THE SIRENS OF TITAN THE NEW-ENGLAND ALMANACK FOR 1814. By Isaac Bickerstaff. Providence, Rhode Island: John Carter. THE NEW-ENGLAND ALMANACK FOR 1814. By Isaac Bickerstaff. Providence: John Carter. Sold also by George Wanton, Newport. 21-year-old Edward Hitchcock calculated and published a COUNTRY ALMANAC (recalculated and reissued each year to 1818). John Farmer’s “A Sketch of Amherst, New Hampshire” (2 COLL. MASS. HIST. SOC. II. BOSTON). Noah Webster, Esq. became a member of the Massachusetts General Court (he would serve also in 1815 and 1817). Carl Phillip Gottfried von Clausewitz was reinstated in the Prussian army. EVENTS OF 1815 HDT WHAT? INDEX 1814 1814 The 2d of 3 volumes of a revised critical edition of an old warhorse, ANTHOLOGIA GRAECA AD FIDEM CODICIS OLIM PALATINI NUNC PARISINI EX APOGRAPHO GOTHANO EDITA ..., prepared by Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Jacobs, appeared in Leipzig (the initial volume had appeared in 1813 and the final volume would appear in 1817). ANTHOLOGIA GRAECA (My working assumption, for which I have no evidence, is that this is likely to have been the unknown edition consulted by Henry Thoreau, from which he would obtain Plutarch materials plus quotes from Crates of Thebes and Simonides’s “Epigram -

Clyde Pharr, the Women of Vanderbilt, and the Wyoming Judge: the Story Behind the Translation of the Theodosian Code in Mid- Century America

Clyde Pharr, the Women of Vanderbilt, and the Wyoming Judge: The Story behind the Translation of the Theodosian Code in Mid- Century America Linda Jones Hall* Abstract — When Clyde Pharr published his massive English translation of the Theodosian Code with Princeton University Press in 1952, two former graduate students at Vanderbilt Uni- versity were acknowledged as co-editors: Theresa Sherrer David- son as Associate Editor and Mary Brown Pharr, Clyde Pharr’s wife, as Assistant Editor. Many other students were involved. This article lays out the role of those students, predominantly women, whose homework assignments, theses, and dissertations provided working drafts for the final volume. Pharr relied heavily * Professor of History, Late Antiquity, St. Mary’s College of Mary- land, St. Mary’s City, Maryland, USA. Acknowledgements follow. Portions of the following items are reproduced by permission and further reproduction is prohibited without the permission of the respective rights holders. The 1949 memorandum and diary of Donald Davidson: © Mary Bell Kirkpatrick. The letters of Chancellor Kirkland to W. L. Fleming and Clyde Pharr; the letter of Chancellor Branscomb to Mrs. Donald Davidson: © Special Collections and University Archives, Jean and Alexander Heard Library, Vanderbilt University. The following items are used by permission. The letters of Clyde Pharr to Dean W. L. Fleming and Chancellor Kirkland; the letter of A. B. Benedict to Chancellor O. C. Carmichael: property of Special Collections and University Archives, Jean and Alexander -

The Essential Rothbard

THE ESSENTIAL ROTHBARD THE ESSENTIAL ROTHBARD DAVID GORDON Ludwig von Mises Institute AUBURN, ALABAMA Copyright © 2007 Ludwig von Mises Institute All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews. For information write the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 518 West Magnolia Avenue, Auburn, Alabama 36832 U.S.A.; www.mises.org. ISBN: 10 digit: 1-933550-10-4 ISBN: 13 digit: 978-1-933550-10-7 CONTENTS Introduction . 7 The Early Years—Becoming a Libertarian . 9 Man, Economy, and State: Rothbard’s Treatise on Economic Theory . 14 Power and Market: The Final Part of Rothbard’s Treatise . 22 More Advances in Economic Theory: The Logic of Action . 26 Rothbard on Money: The Vindication of Gold . 36 Austrian Economic History . 41 A Rothbardian View of American History . 55 The Unknown Rothbard: Unpublished Papers . 63 Rothbard’s System of Ethics . 87 Politics in Theory and Practice . 94 Rothbard on Current Economic Issues . 109 Rothbard’s Last Scholarly Triumph . 113 Followers and Influence . 122 Bibliography . 125 Index . 179 5 INTRODUCTION urray N. Rothbard, a scholar of extraordinary range, made major contributions to economics, history, politi- Mcal philosophy, and legal theory. He developed and extended the Austrian economics of Ludwig von Mises, in whose seminar he was a main participant for many years. He established himself as the principal Austrian theorist in the latter half of the twentieth century and applied Austrian analysis to topics such as the Great Depression of 1929 and the history of American bank- ing. -

Revisiting Mildred Haun's Genre and Literary Craft

From the Margins: Revisiting Mildred Haun’s Genre and Literary Craft By Clarke Sheldon Martin Honors Thesis Department of English and Comparative Literature University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill 2017 Approved: ____________________________________________ 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Irons for her investment this project and in me. I would also like to thank Professor Gwin and Professor McFee for sitting on this committee and for their time and support. I am honored to have received funding from the Department of English and Comparative Literature to present Section IV of this paper at the Mildred Haun Conference in Morristown, Tennessee. Additionally, research for this project was supported by the Tom and Elizabeth Long Excellence Fund for Honors administered by Honors Carolina. Two fantastic librarians made my research for this paper a wonderful experience. Many thanks to Tommy Nixon at UNC Chapel Hill and Molly Dohrmann at Vanderbilt University. Lastly, I want to thank my parents Matthew and Catherine for their encouragement and enthusiasm during my time at Carolina and for their constant love. 3 I Mildred Haun burst onto the Appalachian literary scene when her 1940 book, The Hawk’s Done Gone, was published. The work, a collection of ten stories, offers an in-depth and instructional catalogue of Haun’s native east Tennessee mountain culture through the voice of Mary Dorthula Kanipe, a respected granny-woman trapped in a patriarchal social structure. The Hawk’s Done Gone enjoyed favorable reviews at its time of publication, but it quickly slipped into obscurity. Haun’s short life and complicated relationship with her publisher may have pushed her voice into the margins during her time, but The Hawk’s Done Gone provides cultural observation and connection to a way of life and oral tradition that is deserving of attention today. -

Imagination Movers: the Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism

Imagination Movers: The Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism Seth James Bartee Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought Francois Debrix, Chair Matthew Gabriele Matthew Dallek James Garrison Timothy Luke February 19, 2014 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: conservatism, imagination, historicism, intellectual history counter-narrative, populism, traditionalism, paleo-conservatism Imagination Movers: The Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism Seth James Bartee ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to explore what exactly bound post-Second World War American conservatives together. Since modern conservatism’s recent birth in the United States in the last half century or more, many historians have claimed that both anti-communism and capitalism kept conservatives working in cooperation. My contention was that the intellectual founder of postwar conservatism, Russell Kirk, made imagination, and not anti-communism or capitalism, the thrust behind that movement in his seminal work The Conservative Mind. In The Conservative Mind, published in 1953, Russell Kirk created a conservative genealogy that began with English parliamentarian Edmund Burke. Using Burke and his dislike for the modern revolutionary spirit, Kirk uncovered a supposedly conservative seed that began in late eighteenth-century England, and traced it through various interlocutors into the United States that culminated in the writings of American expatriate poet T.S. Eliot. What Kirk really did was to create a counter-narrative to the American liberal tradition that usually began with the French Revolution and revolutionary figures such as English-American revolutionary Thomas Paine. -

Robert Penn Warren, Cleanth Brooks, and the Southern Literary Tradition Joseph Blotner

Robert Penn Warren Studies Volume 5 Centennial Edition Article 10 2005 Robert Penn Warren, Cleanth Brooks, and the Southern Literary Tradition Joseph Blotner Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/rpwstudies Part of the American Literature Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Blotner, Joseph (2005) "Robert Penn Warren, Cleanth Brooks, and the Southern Literary Tradition," Robert Penn Warren Studies: Vol. 5 , Article 10. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/rpwstudies/vol5/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Penn Warren Studies by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Penn Warren, Cleanth Brooks, and the Southern Literary Tradition JOSEPH BLOTNER By the Southern literary tradition, I mean the works which were there, not some theoretical construct but rather aspects – models and genres – which would be prominent parts of the received tradition Warren and Brooks knew. This will be a speculative attempt, glancing in passing at the massive, two-volume textbook which they wrote and edited with R. W. B. Lewis: American Literature: The Makers and the Making (1973). But it will be difficult to extract a definition from it, as their remarks on their method put us on notice. For example, “William Faulkner has clearly emerged as one of the towering figures in American literary history and would undoubtedly warrant the -

JTHG Corridor

Journey Through Hallowed Ground A National Park Service scheme, run by a “socially-conscious” aristocracy, designed to radically transform a million acres of Virginia’s heartland and to impose the “appropriate” quality of life on people of the Piedmont. 2 © March, 2006, The Virginia Land Rights Coalition POB 85 McDowell, Virginia FOC 24458 540-396-6217 L. M. Schwartz, Chairman www.vlrc.org Reproduction or publication for any purpose or in any commercial media outlet, news source or internet site, either in full or partially, is strictly prohibited without written permission. Printed and bound copies of this report are available in color or black and white. Please inquire. For more information about preserving America’s Constitutionally protected Rights to Life, Liberty and Property, call, write or visit our website. This report may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information, see: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml “Everyone should do all in his power to collect and disseminate the truth, in hope that truth may find a place in history and descend to posterity. History is not the relating of campaigns and battles, and generals or other individuals, but that which shows principles. The principles for which the South contended were government by the people; that is, government by the consent of the governed, government limited and local, free of consolidated power. -

An Austro-Libertarian View, Vol. III

An Austro-Libertarian View, Vol. III An Austro-Libertarian View ESSAYS BY DAVID GORDON VOLUME III CURRENT AFFAIRS • FOREIGN POLICY AMERICAN HISTORY • EUROPEAN HISTORY Mises Institute 518 West Magnolia Avenue Auburn, Alabama 36832-4501 334.321.2100 www.mises.org An Austro-Libertarian View: Essays by David Gordon. Vol. III: Current Affairs, Foreign Policy, American History, European History. Published 2017 by the Mises Institute. This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-NoDerivs 4.0 Interna- tional License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN: 978-1-61016-673-7 Table of Contents by Chapter Titles Preface . xiii Foreword . 1 Current Affairs A Propensity to Self-Subversion . 5 “Social Security and Its Discontents” . 9 Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in 20th-Century America . 11 The Irrepressible Rothbard: The Rothbard-Rockwell Report Essays of Murray N. Rothbard . 17 While America Sleeps: Self-Delusion, Military Weakness, and the Threat to Peace Today . 23 The War Over Iraq: Saddam’s Tyranny and America’s Mission . 29 Why We Fight: Moral Clarity and the War on Terrorism . 35 Speaking of Liberty . 39 Against Leviathan: Government Power and a Free Society . 45 No Victory, No Peace . 51 Resurgence of the Warfare State: The Crisis Since 9/11 . 57 In Our Hands: A Plan to Replace the Welfare State . 63 World War IV: The Long Struggle Against Islamofascism . 71 Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement . 77 The Meaning of Sarkozy . 85 The Power Problem: How American Military Dominance Makes Us Less Safe, Less Prosperous, and Less Free . -

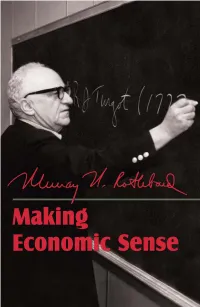

Making Economic Sense.Pdf

Making Economic Sense 2nd Edition Murray N. Rothbard Ludwig von Mises Institute AUBURN, ALABAMA Copyright © 1995, 2006 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews. For information write the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 518 West Magnolia Avenue, Auburn, Alabama 36832. ISBN: 0-945466-46-3 CONTENTS Preface by Llewellyn H. Rockwell, Jr. .xi Introduction to the Second Edition by Robert P. Murphy . .xiii MAKING ECONOMIC SENSE 1 Is It the “Economy, Stupid”? . .3 2 Ten Great Economic Myths . .7 3 Discussing the “Issues” . .19 4 Creative Economic Semantics . .23 5 Chaos Theory: Destroying Mathematical Economics From Within? . .25 6 Statistics: Destroyed From Within? . .28 7 The Consequences of Human Action: Intended or Unintended? . .31 8 The Interest Rate Question . .33 9 Are Savings Too Low? . .37 10 A Walk on the Supply Side . .40 11 Keynesian Myths . .43 12 Keynesianism Redux . .45 v vi Making Economic Sense THE SOCIALISM OF WELFARE 13 Economic Incentives and Welfare . .53 14 Welfare as We Don’t Know It . .56 15 The Infant Mortality “Crisis” . .58 16 The Homeless and the Hungry . .62 17 Rioting for Rage, Fun, and Profit . .64 18 The Social Security Swindle . .68 19 Roots of the Insurance Crisis . .71 20 Government Medical “Insurance” . .74 21 The Neocon Welfare State . .77 22 By Their Fruits . .81 23 The Politics of Famine . .84 24 Government vs. Natural Resources . .87 25 Environmentalists Clobber Texas . .89 26 Government and Hurricane Hugo: A Deadly Combination . -

Theoretical Perspectives on Party Polarization in America

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-19592-9 — Party Polarization in America B. Dan Wood , Soren Jordan Index More Information 1 Theoretical Perspectives on Party Polarization in America On February 28, 2012, Senator Olympia Snowe (R-Maine) announced her decision to retire after eighteen years in the U.S. Senate. Explaining her deci- sion, she said, I have spoken on the floor of the Senate for years about the dysfunction and political polarization in the institution. Simply put, the Senate is not living up to what the Founding Fathers envisioned ... During the Federal Convention of 1787, James Madison wrote in his Notes of Debates that “the use of the Senate is to consist in its proceedings with more coolness, with more system, and with more wisdom, than the popular branch.” ... Yet more than 200 years later, the greatest deliberative body in history is not living up to its billing ...everyone simply votes with their party and those in charge employ every possible tactic to block the other side. But that is not what America is all about, and it’s not what the Founders intended. (Madison 1787, June 7; Snowe 2012) Senator Snowe was not alone in her frustration with the polarization and dysfunction of the U.S. Congress. In the 2010 and 2012 election cycles, twenty-five senators and sixty-five House members either retired or resigned (Chamberlain 2012), with another seven senators and forty-one House members retiring in 2014 (Ballotpedia 2016). Many of these incumbents expressed sentiment similar to Senator Snowe’s. Referring to the poisonous nature of politics in Washington, Representative Steve Latourette (R-Ohio) stated, “I have reached the conclusion that the atmosphere today and the reality that exists in the House of Representatives no longer encourages the finding of common ground.” LaTourette told reporters that to rise in party ranks, politicians must now hand over “your wallet and your voting card” to party extremes, and he was uninterested (Helderman 2012). -

Race, Women, and the South: Faulkner’S Connection to and Separation from the Fugitive-Agrarian Tradition

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-2005 Race, Women, and the South: Faulkner’s Connection to and Separation from the Fugitive-Agrarian Tradition Brandi Stearns University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Stearns, Brandi, "Race, Women, and the South: Faulkner’s Connection to and Separation from the Fugitive- Agrarian Tradition. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2005. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2359 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Brandi Stearns entitled "Race, Women, and the South: Faulkner’s Connection to and Separation from the Fugitive-Agrarian Tradition." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Thomas Haddox, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary Papke, Allison Ensor Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Brandi Stearns entitled “Race, Women, and the South: Faulkner’s Connection to and Separation from the Fugitive-Agrarian Tradition.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. -

The Corruption of American Conservatism

The Corruption of American Conservatism Iskander Rehman December 2017 Cover photo credits: Jim Larkin/Shutterstock.com December 2017 THE CORRUPTION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM Iskander Rehman It is true that courtiers in America do not say ‘Sire’ and ‘Your Majesty’—a great and capital difference; but they speak constantly of the natural enlightenment of their master; they do not hold a competition on the question of knowing which one of the virtues of the prince most merits being admired; for they are sure that he possesses all the virtues, without having acquired them and so to speak without wanting to do so; they do not give them their wives and daughters so that he may deign to elevate them to the rank of their mistresses; but in sacrificing their opinions to him, they prostitute themselves. - Alexis de Tocqueville, On Democracy in America, Vol.I, Part 2, Chapter 7. n a sunny morning in January 1962, an to a crackpot fringe of “Commie-haunted apple editor, a philosopher and a presidential pickers and cactus drunks,” but also included Oaspirant huddled in a Florida hotel prominent Arizonians—some of whom had room. The topic of discussion was a deranged expressed sympathy for his candidacy. For candy manufacturer, Robert Welch. Welch, William F. Buckley and Russell Kirk, however, the a millionaire, was the head of the John Birch Birchers were a tumorous outgrowth of American Society, an extremist movement that trafficked in conservatism, and one that needed to be carefully anti-communist hysteria and absurd conspiracy excised. Buckley later recalled himself thinking, theories—most notably claiming that President “How can the John Birch Society be an effective Eisenhower had been a “conscious Communist political instrument while it is led by a man whose agent.”1 Troubled by the growing popularity of the views on current affairs are at so many critical movement, William F.