Schrödinger and Nietzsche on Life: the Eternal Recurrence of the Same

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment Coversheet & Feedback Form

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment coversheet & feedback form THIS SHEET MUST BE THE FIRST PAGE OF THE ASSIGNMENT YOU ARE SUBMITTING (DO NOT SEND AS A SEPARATE FILE) For completion by the student: Student Name: SAMANTHA JANE HOLLAND Student University Email: [email protected] Module code: Student ID number: Educational support needs: 1001693 Yes/No Module title: DISSERTATION Assignment title: OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Assignment due date: 2 April 2013 This assignment is for the 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th module of the degree N/A Word count: 22,000 WORDS I confirm that this is my original work and that I have adhered to the University policy on plagiarism. Signed …………………………………………………………… Assignment Mark 1st Marker’s Provisional mark 2nd Marker’s/Moderator’s provisional mark External Examiner’s mark (if relevant) Final Mark NB. All marks are provisional until confirmed by the Final Examination Board. For completion by Marker 1 : Comments: Marker’s signature: Date: For completion by Marker 2/Moderator: Comments: Marker’s Signature: Date: External Examiner’s comments (if relevant) External Examiner’s Signature: Date: ii OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Samantha Jane Holland March 2013 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA Nature University of Wales, Trinity Saint David Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. -

Voronina, "Comments on Krzysztof Michalski's the Flame of Eternity

Volume 8, No 1, Spring 2013 ISSN 1932-1066 Comments on Krzysztof Michalski's The Flame of Eternity Lydia Voronina Boston, MA [email protected] Abstract: Emphasizing romantic tendencies in Nietzsche's philosophy allowed Krzysztof Michalski to build a more comprehensive context for the understanding of his most cryptic philosophical concepts, such as Nihilism, Over- man, the Will to power, the Eternal Return. Describing life in terms of constant advancement of itself, opening new possibilities, the flame which "ignites" human body and soul, etc, also positioned Michalski closer to spirituality as a human condition and existential interpretation of Christianity which implies reliving life and death of Christ as a real event that one lives through and that burns one's heart, i.e. not as leaned from reading texts or listening to a teacher. The image of fire implies constant changing, unrest, never-ending passing away and becoming phases of reality and seems losing its present phase. This makes Michalski's perspective on Nietzsche and his existential view of Christianity vulnerable because both of them lack a sufficient foundation for the sustainable present that requires various constants and makes it possible for life to be lived. Keywords: Nietzsche, Friedrich; life; eternity; spontaneity; spirituality; Romanticism; existential Christianity; death of God; eternal return; overman; time; temporality. People often say that to understand a Romantic you have occurrence of itself through the eternal game of self- to be even a more incurable Romantic or to understand a asserting forces, becomes Michalski's major explanatory mystic you have to be a more comprehensive mystic. -

Nietzsche and the Pathologies of Meaning

Nietzsche and the Pathologies of Meaning Jeremy James Forster Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Jeremy James Forster All rights reserved ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE AND THE PATHOLOGIES OF MEANING Jeremy Forster My dissertation details what Nietzsche sees as a normative and philosophical crisis that arises in modern society. This crisis involves a growing sense of malaise that leads to large-scale questions about whether life in the modern world can be seen as meaningful and good. I claim that confronting this problem is a central concern throughout Nietzsche’s philosophical career, but that his understanding of this problem and its solution shifts throughout different phases of his thinking. Part of what is unique to Nietzsche’s treatment of this problem is his understanding that attempts to imbue existence with meaning are self-undermining, becoming pathological and only further entrenching the problem. Nietzsche’s solution to this problem ultimately resides in treating meaning as a spiritual need that can only be fulfilled through a creative interpretive process. CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter I: The Birth of Tragedy and the Problem of Meaning 30 Part I: Background 33 Part II: Meaningfulness in Artistic Cultures 45 Part III: Meaningfulness in Tragic Cultures 59 Part IV: Meaningfulness in Socratic Cultures 70 Conclusion: The Solution to Socratism 78 Chapter II: Meaning, Science, and the “Perceptions of Science -

The Scope of the Argument from Species Overlap

bs_bs_banner Journal of Applied Philosophy,Vol.31, No. 2, 2014 doi: 10.1111/japp.12051 The Scope of the Argument from Species Overlap OSCAR HORTA ABSTRACT The argument from species overlap has been widely used in the literature on animal ethics and speciesism. However, there has been much confusion regarding what the argument proves and what it does not prove, and regarding the views it challenges.This article intends to clarify these confusions, and to show that the name most often used for this argument (‘the argument from marginal cases’) reflects and reinforces these misunderstandings.The article claims that the argument questions not only those defences of anthropocentrism that appeal to capacities believed to be typically human, but also those that appeal to special relations between humans. This means the scope of the argument is far wider than has been thought thus far. Finally, the article claims that, even if the argument cannot prove by itself that we should not disregard the interests of nonhuman animals, it provides us with strong reasons to do so, since the argument does prove that no defence of anthropocentrism appealing to non-definitional and testable criteria succeeds. 1. Introduction The argument from species overlap, which has also been called — misleadingly, I will argue — the argument from marginal cases, points out that the criteria that are com- monly used to deprive nonhuman animals of moral consideration fail to draw a line between human beings and other sentient animals, since there are also humans who fail to satisfy them.1 This argument has been widely used in the literature on animal ethics for two purposes. -

PHIL 221 – Ethical Theory (3 Credits) Course Description

PHIL 221 – Ethical Theory (3 credits) Course Description: This course focuses on theories of morality rather than on contemporary moral issues (that is the topic of PHIL 120). That means that we will primarily be preoccupied with exploring what it means for an action—or a person—to be “good”. We will attempt to answer this question by looking at a mix of historical and contemporary texts primarily drawn from the Western European tradition, but also including some works from China and pre-colonial central America. We will begin by asking whether there are any universal and objectively valid moral rules, and chart several attempts to answer in both the affirmative and the negative: relativism, egoism, virtue ethics, consequentialism, deontology, the ethics of care, and contractarianism. We will consider the relationship between morality and the law, and whether morality is linked to human happiness. Finally, we will consider arguments for and against the idea that moral facts actually exist. Schedule of Readings Week 1 Introduction What are we trying to do? Charles L. Stevenson – The Nature of Ethical Disagreement Tom Regan – How Not to Answer Moral Questions Week 2 Relativism What counts as good depends on the moral standards of the group doing the evaluating. Mary Midgley – Trying Out One’s New Sword Martha Nussbaum – Judging Other Cultures: The Case of Genital Mutilation Plato – The Myth of Gyges (Republic II) Week 3 Egoism What’s good is just what’s good for me. Mencius – Mengzi (excerpts) James Rachels – Egoism and Moral Skepticism Week 4 Virtue Ethics Morality depends on having a virtuous character. -

Review Of" Science and Poetry" by M. Midgley

Swarthmore College Works Philosophy Faculty Works Philosophy 10-1-2003 Review Of "Science And Poetry" By M. Midgley Hans Oberdiek Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy Part of the Philosophy Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Hans Oberdiek. (2003). "Review Of "Science And Poetry" By M. Midgley". Ethics. Volume 114, Issue 1. 187-189. DOI: 10.1086/376710 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy/121 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mary Midgley, Science and Poetry Science and Poetry by Mary. Midgley, Review by: Reviewed by Hans Oberdiek Ethics, Vol. 114, No. 1 (October 2003), pp. 187-189 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/376710 . Accessed: 09/06/2015 16:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ethics. -

Yesterday, Today, and Forever Hebrews 13:8 a Sermon Preached in Duke University Chapel on August 29, 2010 by the Revd Dr Sam Wells

Yesterday, Today, and Forever Hebrews 13:8 A Sermon preached in Duke University Chapel on August 29, 2010 by the Revd Dr Sam Wells Who are you? This is a question we only get to ask one another in the movies. The convention is for the question to be addressed by a woman to a handsome man just as she’s beginning to realize he isn’t the uncomplicated body-and-soulmate he first seemed to be. Here’s one typical scenario: the war is starting to go badly; the chief of the special unit takes a key officer aside, and sends him on a dangerous mission to infiltrate the enemy forces. This being Hollywood, the officer falls in love with a beautiful woman while in enemy territory. In a moment of passion and mystery, it dawns on her that he’s not like the local men. So her bewitched but mistrusting eyes stare into his, and she says, “Who are you?” Then there’s the science fiction version. In this case the man develops an annoying habit of suddenly, without warning, traveling in time, or turning into a caped superhero. Meanwhile the woman, though drawn to his awesome good looks and sympathetic to his commendable desire to save the universe, yet finds herself taking his unexpected and unusual absences rather personally. So on one of the few occasions she gets to look into his eyes when they’re not undergoing some kind of chemical transformation, she says, with the now-familiar, bewitched-but-mistrusting expression, “Who are you?” “Who are you?” We never ask one another this question for fear of sounding melodramatic, like we’re in a movie. -

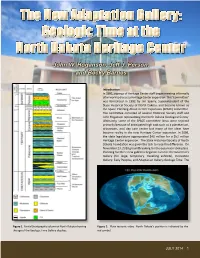

The New Adaption Gallery

Introduction In 1991, a group of Heritage Center staff began meeting informally after work to discuss a Heritage Center expansion. This “committee” was formalized in 1992 by Jim Sperry, Superintendent of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, and became known as the Space Planning About Center Expansion (SPACE) committee. The committee consisted of several Historical Society staff and John Hoganson representing the North Dakota Geological Survey. Ultimately, some of the SPACE committee ideas were rejected primarily because of anticipated high cost such as a planetarium, arboretum, and day care center but many of the ideas have become reality in the new Heritage Center expansion. In 2009, the state legislature appropriated $40 million for a $52 million Heritage Center expansion. The State Historical Society of North Dakota Foundation was given the task to raise the difference. On November 23, 2010 groundbreaking for the expansion took place. Planning for three new galleries began in earnest: the Governor’s Gallery (for large, temporary, travelling exhibits), Innovation Gallery: Early Peoples, and Adaptation Gallery: Geologic Time. The Figure 1. Partial Stratigraphic column of North Dakota showing Figure 2. Plate tectonic video. North Dakota's position is indicated by the the age of the Geologic Time Gallery displays. red symbol. JULY 2014 1 Orientation Featured in the Orientation area is an interactive touch table that provides a timeline of geological and evolutionary events in North Dakota from 600 million years ago to the present. Visitors activate the timeline by scrolling to learn how the geology, environment, climate, and life have changed in North Dakota through time. -

Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence Philip J

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Philosophy College of Arts & Sciences Spring 2007 Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence Philip J. Kain Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/phi Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Kain, P. J. "Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence," The ourJ nal of Nietzsche Studies, 33 (2007): 49-63. Copyright © 2007 The eP nnsylvania State University Press. This article is used by permission of The eP nnsylvania State University Press. http://doi.org/10.1353/nie.2007.0007 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence PHILIP J. KAIN I t the center ofNietzsche's vision lies his concept of the "terror and horror A of existence" (BT 3). As he puts it in The Birth of Tragedy: There is an ancient story that King Midas hunted in the forest a long time for the wise Silenus, the companion of Dionysus .... When Silenus at last fell into his hands, the king asked what was the best and most desirable of all things for man. Fixed and immovable, the demigod said not a word, till at last, urged by the king, he gave a shrill laugh and broke out into these words: "Oh, wretched ephemeral race, children of chance and misery, why do you compel me to tell you what it would be most expedient for you not to hear? What is best of all is utterly beyond your reach: not to be born, not to be, to be nothing. -

Nietzsche for Physicists

Nietzsche for physicists Juliano C. S. Neves∗ Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP), Instituto de Matemática, Estatística e Computação Científica, CEP. 13083-859, Campinas, SP, Brazil Abstract One of the most important philosophers in history, the German Friedrich Nietzsche, is almost ignored by physicists. This author who declared the death of God in the 19th century was a science enthusiast, especially in the second period of his work. With the aid of the physical concept of force, Nietzsche created his concept of will to power. After thinking about energy conservation, the German philosopher had some inspiration for creating his concept of eternal recurrence. In this article, some influences of physics on Nietzsche are pointed out, and the topicality of his epistemological position—the perspectivism—is discussed. Considering the concept of will to power, I propose that the perspectivism leads to an interpretation where physics and science in general are viewed as a game. Keywords: Perspectivism, Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, Physics 1 Introduction: an obscure philosopher? The man who said “God is dead” (GS §108)1 is a popular philosopher well-regarded world- wide. Nietzsche is a strong reference in philosophy, psychology, sociology and the arts. But did Nietzsche have any influence on natural sciences, especially on physics? Among physi- cists and scientists in general, the thinker who created a philosophy that argues against the Platonism is known as an obscure or irrationalist philosopher. However, contrary to common arXiv:1611.08193v3 [physics.hist-ph] 15 May 2018 ideas, although Nietzsche was critical about absolute rationalism, he was not an irrationalist. Nietzsche criticized the hubris of reason (the Socratic rationalism2): the belief that mankind ∗[email protected] 1Nietzsche’s works are indicated by the initials, with the correspondent sections or aphorisms, established by the critical edition of the complete works edited by Colli and Montinari [Nietzsche, 1978]. -

Nietzsche's Engagements with Kant and the Kantian Legacy, Vol

Nietzsche's Engagements with Kant and the Kantian Legacy, vol. 1: Nietzsche, Kant, and the Problem of Metaphysics ed. by Marco Brusotti and Herman Siemens (review) Justin Remhof The Journal of Nietzsche Studies, Volume 52, Issue 1, Spring 2021, pp. 177-184 (Review) Published by Penn State University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/788332 [ Access provided at 22 Apr 2021 16:37 GMT from Old Dominion Libraries & (Viva) ] BOOK REVIEWS | 177 Rather than reducing the will to power to individual aggressivity, this idea must at least be understood historically such that it accommodates Nietzsche’s abiding sense that early human existence was “constantly imperiled” (D 18, see also D 23), and that we were the “most endangered animal” in dire need of “help and protection” (GS 354; see also GM II:19, III:13). It is under these circumstances that our will to power initially emerges. It is surely against this backdrop that Nietzsche accepts the ethnological vision of prehistoric humans surviving in a variety of kin-based communities (Geschlechtsgenossenschaften), from the most basic largely promiscuous and egalitarian matriarchal hordes to more hierarchical, patriarchal, and ordered tribal associations. These dif- ferent kinds of kin-based communities can exist at the same time and wage desperate wars with each other for survival. It is only such a view that makes sense of the sudden appearance of those “unconscious artists” who are “orga- nized on a war footing [. .] with the power to organize” (GM II:17), such that they can take advantage of the less organized, more peaceful communities. -

Hebrews 13:8 Jesus Christ the Eternal Unchanging Son Of

Hebrews 13:8 The Unchanging Christ is the Same Forever Jesus Christ the Messiah is eternally trustworthy. The writer of Hebrews simply said, "Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today and forever" (Hebrews 13:8). In a turbulent and fast-changing world that goes from one crisis to the next nothing seems permanent. However, this statement of faith has been a source of strength and encouragement for Christians in every generation for centuries. In a world that is flying apart politically, economically, personally and spiritually Jesus Christ is our only secure anchor. Through all the changes in society, the church around us, and in our spiritual life within us, Jesus Christ changes not. He is ever the same. As our personal faith seizes hold of Him we will participate in His unchangeableness. Like Christ it will know no change, and will always be the same. He is just as faithful now as He has ever been. Jesus Christ is the same for all eternity. He is changeless, immutable! He has not changed, and He will never change. The same one who was the source and object of triumphant faith yesterday is also the one who is all-sufficient and all-powerful today to save, sustain and guide us into the eternal future. He will continue to be our Savior forever. He steadily says to us, "I will never fail you nor forsake you." In His awesome prayer the night before His death by crucifixion, Jesus prayed, "Now, Father, glorify Me together with Yourself, with the glory which I had with You before the world was" (John 17:5).