A Study of Mohan Rakesh's Lehron Ke Rajhans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AXC Instructions / ૂચના

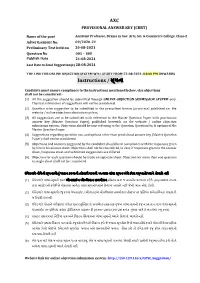

AXC PROVISIONAL ANSWER KEY (CBRT) Name of the post Assistant Professor, Drama in Gov. Arts, Sci. & Commerce College, Class-2 Advertisement No. 69/2020-21 Preliminary Test held on 20-08-2021 Question No 001 – 300 Publish Date 21-08-2021 Last Date to Send Suggestion(s) 28-08-2021 THE LINK FOR ONLINE OBJECTION SYSTEM WILL START FROM 22-08-2021; 04:00 PM ONWARDS Instructions / ચનાૂ Candidate must ensure compliance to the instructions mentioned below, else objections shall not be considered: - (1) All the suggestion should be submitted through ONLINE OBJECTION SUBMISSION SYSTEM only. Physical submission of suggestions will not be considered. (2) Question wise suggestion to be submitted in the prescribed format (proforma) published on the website / online objection submission system. (3) All suggestions are to be submitted with reference to the Master Question Paper with provisional answer key (Master Question Paper), published herewith on the website / online objection submission system. Objections should be sent referring to the Question, Question No. & options of the Master Question Paper. (4) Suggestions regarding question nos. and options other than provisional answer key (Master Question Paper) shall not be considered. (5) Objections and answers suggested by the candidate should be in compliance with the responses given by him in his answer sheet. Objections shall not be considered, in case, if responses given in the answer sheet /response sheet and submitted suggestions are differed. (6) Objection for each question should be made on separate sheet. Objection for more than one question in single sheet shall not be considered. ઉમેદવાર નીચેની ૂચનાઓું પાલન કરવાની તકદાર રાખવી, અયથા વાંધા- ૂચન ગે કરલ રૂઆતો યાને લેવાશે નહ (1) ઉમેદવાર વાંધાં- ૂચનો ફત ઓનલાઈન ઓશન સબમીશન સીટમ ારા જ સબમીટ કરવાના રહશે. -

UGC MHRD E Pathshala

UGC MHRD e Pathshala Subject: English Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Paper 09: Comparative Literature: Drama in India Paper Coordinator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Module 09:Theatre: Architecture, Apparatus, Acting; Censorship and Spectatorship; Translations and Adaptations Content Writer: Mr. Benil Biswas, Ambedkar University Delhi Content Reviewer: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Language Editor: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee, University of Hyderabad Introduction: To be a painter one must know sculpture To be an architect one must know dance Dance is possible only through music And poetry therefore is essential (Part 2 of Vishnu Dharmottara Purana, an exchange between the sage Markandya and King Vajra)1 Quite appropriately Theatre encompasses all the above mentions arts, which is vital for an individual and community’s overall development. India is known for its rich cultural heritage has harnessed the energy of theatrical forms since the inception of its civilization. A rich cultural heritage of almost 3000 years has been the nurturing ground for Theatre and its Folk forms. Emerging after Greek and Roman theatre, Sanskrit theatre closely associated with primordial rituals, is the earliest form of Indian Theatre. Ascribed to Bharat Muni, ‘Natya Sastra or Natyashastra’2 is considered to be the initial and most elaborate treatise on dramaturgy and art of theatre in the world. It gives the detailed account of Indian theatre’s divine origin and expounds Rasa. This text becomes the basis of the classical Sanskrit theatre in India. Sanskrit Theatre was nourished by pre-eminent play-wrights like Bhasa, Kalidasa, Shudraka, Vishakadatta, Bhavabhuti and Harsha.3 This body of works which were sophisticated in its form and thematic content can be equaled in its range and influence with the dramatic yield of other prosperous theatre traditions of the world like ancient Greek theatre and Elizabethan theatre. -

Girish Karnad 1 Girish Karnad

Girish Karnad 1 Girish Karnad Girish Karnad Born Girish Raghunath Karnad 19 May 1938 Matheran, British India (present-day Maharashtra, India) Occupation Playwright, film director, film actor, poet Nationality Indian Alma mater University of Oxford Genres Fiction Literary movement Navya Notable work(s) Tughalak 1964 Taledanda Girish Raghunath Karnad (born 19 May 1938) is a contemporary writer, playwright, screenwriter, actor and movie director in Kannada language. His rise as a playwright in 1960s, marked the coming of age of Modern Indian playwriting in Kannada, just as Badal Sarkar did in Bengali, Vijay Tendulkar in Marathi, and Mohan Rakesh in Hindi.[1] He is a recipient[2] of the 1998 Jnanpith Award, the highest literary honour conferred in India. For four decades Karnad has been composing plays, often using history and mythology to tackle contemporary issues. He has translated his plays into English and has received acclaim.[3] His plays have been translated into some Indian languages and directed by directors like Ebrahim Alkazi, B. V. Karanth, Alyque Padamsee, Prasanna, Arvind Gaur, Satyadev Dubey, Vijaya Mehta, Shyamanand Jalan and Amal Allana.[3] He is active in the world of Indian cinema working as an actor, director, and screenwriter, in Hindi and Kannada flicks, earning awards along the way. He was conferred Padma Shri and Padma Bhushan by the Government of India and won four Filmfare Awards where three are Filmfare Award for Best Director - Kannada and one Filmfare Best Screenplay Award. Early life and education Girish Karnad was born in Matheran, Maharashtra. His initial schooling was in Marathi. In Sirsi, Karnataka, he was exposed to travelling theatre groups, Natak Mandalis as his parents were deeply interested in their plays.[4] As a youngster, Karnad was an ardent admirer of Yakshagana and the theater in his village.[] He earned his Bachelors of Arts degree in Mathematics and Statistics, from Karnatak Arts College, Dharwad (Karnataka University), in 1958. -

Foojf.Kdk ROSPECTUS Ear Residentialcer Course Indramaticar Tificate

ROSPECTUS NSD SIKKIM one year residential certificate foojf.kdkcourse in dramatic arts 2020 NSD SIKKIMGovt. of Sikkim has allotted a piece of land to National School of Drama, Sikkim in 2019 to establish its own permanent infrastructure at Assam Lingzey Forest Block, near Gangtok. Front cover photo: Letter of allotment of the land Kalidasa’s Abhijnan Shakuntalam, Official Map of the land Dir. Piyal Bhattacharya, (Student’s Production, 2019) Way to Saurani Phatak Land of Social Justice & Welfare Dept. Private Holding ICDS Centre Private Holding Govt. of Sikkim Land position in Private Holding the Google Map Kanchanjangha Peak Contents 3 National School of Drama, New Delhi 4 Former Chairpersons & Directors of NSD 5 National School of Drama, Sikkim 6 The Chairman, NSD Society 7 The Director, NSD 8 The Centre In-charge, NSD 9 The Centre Director, NSD Sikkim 11 The Vision & Objectives of NSD, Sikkim 12 Subjects of Study 14 Syllabus 16 Annual Activity Report 18 Visiting Faculty Members 19 Admission Related Matters 22 General Information 24 NSD Sikkim Repertory Company 26 Administrative & Technical Staff 28 Theatre Festivals Location & Travel Route English C3 Hami Nai Aafai Aaf, a dramatisation of Padma Sachdev’s Dogri Novel Ab Na Banegi Dehri, Dir. Bipin Kumar (Students/Repertory Production, 2011/12) National School of Drama ational School of Drama is one of the foremost theatre training institutions in the world and the Nonly one of its kind in India. Established in 1959 as a constituent unit of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, the School became an independent entity in 1975 and was registered as an autonomous organization under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860, fully financed by the Ministry of Culture, Government of India. -

Hindi DVD Database 2014-2015 Full-Ready

Malayalam Entertainment Portal Presents Hindi DVD Database 2014-2015 2014 Full (Fourth Edition) • Details of more than 290 Hindi Movie DVD Titles Compiled by Rajiv Nedungadi Disclaimer All contents provided in this file, available through any media or source, or online through any website or groups or forums, are only the details or information collected or compiled to provide information about music and movies to general public. These reports or information are compiled or collected from the inlay cards accompanied with the copyrighted CDs or from information on websites and we do not guarantee any accuracy of any information and is not responsible for missing information or for results obtained from the use of this information and especially states that it has no financial liability whatsoever to the users of this report. The prices of items and copyright holders mentioned may vary from time to time. The database is only for reference and does not include songs or videos. Titles can be purchased from the respective copyright owners or leading music stores. This database has been compiled by Rajiv Nedungadi, who owns a copy of the original Audio or Video CD or DVD or Blu Ray of the titles mentioned in the database. The synopsis of movies mentioned in the database are from the inlay card of the disc or from the free encyclopedia www.wikipedia.org . Media Arranged By: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Lifeline/762365430471414 © 2010-2013 Kiran Data Services | 2013-2015 Malayalam Entertainment Portal MALAYALAM ENTERTAINMENT PORTAL For Exclusive -

Theatre & Television Production

FACULTY OF VISUAL ARTS & PERFORMING ARTS Syllabus For MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) (Semester: I – IV) Session: 2019–20 GURU NANAK DEV UNIVERSITY AMRITSAR Note: (i) Copy rights are reserved. Nobody is allowed to print it in any form. Defaulters will be prosecuted. (ii) Subject to change in the syllabi at any time. Please visit the University website time to time. 1 MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) SEMESTER SYSTEM Eligibility: i) Students who have passed B.Voc. (Theatre) from a recognised University or have attained NSQF Level 7 in a particular Industrial Sector in the same Trade OR ii) Bachelor Degree with atleast 50% marks from a recognised University. Semester – I: Courses Hours Marks Paper-I History & Elements of Theatre Theory 3 100 Paper-II Western Drama and Architecture Theory 3 100 Paper-III Punjabi Theatre Theory 3 100 Paper-IV Acting Orientation Practical 3 100 Paper-V Fundamentals of Design Practical 3 100 Semester – II: Courses Hours Marks Paper-I Western Theatre Theory 3 100 Paper-II Fundamentals of Directions Theory 3 100 Paper-III Theatre Production Practical 3 100 Paper-IV Production Management Practical 3 100 Paper-V Stage Craft (Make Up) Practical 3 100 2 MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) SEMESTER SYSTEM Semester – III Courses Hours Marks Paper-I INDIAN THEATRE Theory 3 100 Paper-II MODERN THEATRE & Theory 3 100 INDIAN FOLK THEATRE Paper-III STAGE CRAFT Theory 3 100 Paper-IV PRODUCTION PROJECT Practical 3 100 Paper-V PRODUCTION ANALYSIS Practical 3 100 AND VIVA Semester – IV Courses Hours Marks Paper-I RESEARCH METHODOLOGY Theory 3 100 Paper-II SCREEN ACTING Theory 3 100 Paper-III ACTING Theory 3 100 Paper-IV TELEVISION AND FILM Practical 3 100 APPRECIATION Paper-V FILM PRODUCTION Practical 3 100 3 MASTER OF VOCATION (M.VOC.) (THEATRE & TELEVISION PRODUCTION) SEMESTER – I PAPER-I: HISTORY AND ELEMENTS OF THEATRE (Theory) Time: 3 Hours Max. -

M.P.A (Theatre Arts)

'. Code No: N-35 ENTRANCE EXAMINATION, 2017 M.P.A (Theatre Arts) MAX.MARKS:50 DATE: 04 -06-2017 TIME: 10:00 AM Duration 2 hours HALL TICKET NO: __________ Instructions: i) Write your Hall Ticket Number in OMR Answer Sheet given to you. Also write the Hall Ticket Number in the space provided above. ii) There is negative marking. Each wrong answer carries-O.33mark. iii) Answers are to be marked on OMR answer sheet following the instructions provided there upon. iv) Hand over the OMR answer sheet at the end of the examination to the Invigilator. v) No additional sheets will be provided. Rough work can be done in the question paper itself/ space provided at the end of the booklet. 1. The author of the play "Nagamandala" is ______ A) Chandrashekhara Kambar C) Bhartendu Harishchandra B) B.Y Karant D) Girish Karnad 2. Guru Birju Maharaj is an exponent of the form _____ A) Kathakali C) Kathak B) Kuchipudi D) Odissi 3. Founder of the theatre group 'Kalakshetra Manipur' is. _______ A) Ratan Thiyam C) Lokendra Arambam, B) Heisnam Kanhailal, D) S. Thanilleirna 1 '. 4. World theatre day is celebrated on ________ A) December 25 C) March 27 B) November 14 D) January 26 5. Rabindranath Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize in the field of______ _ A) Architecture C) Sports B) Sculpture D) Literature 6. The director of the play "Charan Das Chor" of Nay a Theatre group is ______ A) Utpal Dutt C) Ram Gopal Bajaj B) Habib Tanvir, D) Badal Sarkar 7. 'Sopanam,' the theatre wing of Bhasabharati, the Centre for Performing Arts founded by ______ A) Deepan Shivaraman C) Ratan Thiyam B) C RJambe D) Kavalam Narayana Panikkar 8. -

The Master Playwrights and Directors

THE MASTER PLAYWRIGHTS AND DIRECTORS BIJAN BHATTACHARYA (1915–77), playwright, actor, director; whole-time member, Communist Party, actively associated with Progressive Writers and Artists Association and the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA); wrote and co-directed Nabanna (1944) for IPTA, starting off the new theatre movement in Bengal and continued to lead groups like Calcutta Theatre and Kabachkundal, with plays like Mora Chand (1961), Debigarjan [for the historic National Integration and Peace Conference on 21 February 1966 in Wellington Square, Calcutta], and Garbhabati Janani (1969), all of which he wrote and directed; acted in films directed by Ritwik Ghatak [Meghey Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961), Subarnarekha (1962), Jukti, Takko aar Gappo (1974)] and Mrinal Sen [Padatik (1973)]. Recipient of state and national awards, including the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for Playwriting in 1975. SOMBHU MITRA (1915–97), actor-director, playwright; led the theatre group Bohurupee till the early 1970s, which brought together some of the finest literary and cultural minds of the times, initiating a culture of ideation and producing good plays; best known for his productions of Dashachakra (1952), Raktakarabi (1954), Putulkhela (1958), Raja Oidipous (1964), Raja (1964), Pagla Ghoda (1971). Recipient of Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for Direction (1959), Fellow of the Sangeet Natak Akademi (1966), Padmabhushan (1970), Magsaysay Award (1976), Kalidas Samman (1983). HABIB TANVIR (1923–2009) joined the Indian People’s Theatre Association in the late forties, directing and acting in street plays for industrial workers in Mumbai; before moving to Delhi in 1954, when he produced the first version of Agra Bazar; followed by a training at the RADA, a course that left him dissatisfied, and he left incomplete. -

'The Psychiatry Ward Became a School of Acting for Me.'

'The psychiatry ward became a school of acting for me.' Mohan Agashe MOHAN AGASHE the reputed stage and film actor, is also a psychiatrist. This free-flowing interview for STQ, with SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY in August 1995, captures the flavour of conversation and explores, amongst other things, the links between psychiatry and theatre. STQ: Maybe if you start with a little bit of the Marathi theatre setting ... what theatre you first saw, or even personal stuff, growing up and that kind of thing ... 'My theatre career ... had an insidious onset' MA: That makes sense to me, I'll tell you why, because, just as some diseases have an insidious onset, my theatre career-you could say-had an insidious onset. For a pretty long time 1 I did not know what I was doing or why I was doing it. Almost about 10 to 15 years later I suddenly found I had serious interest in theatre. And generally you put these questions to test when you have to make a choice. Till then you're just playing about. At each point of time, I realized, you are making a decision which is irreversible. When you reach that point, then you seriously think about it, whether it is theatre, marriage or studies, whatever it is. That's why I say it is insidious-for most of the theatre practitioners it generally starts very early in life. For me it started with school because I used to do mimicries. I loved it and I imitated most of my teachers. I was very keen to perform in Ganesh Festivals, Durga Puja festivals-I used to cry if my item was left out. -

So Far Scholars and Critics in India Have Been Discussing Themes and Quite Rarely, Their Technical Experiments of These Playwrights

2 Need of the Research Work So far scholars and critics in India have been discussing themes and quite rarely, their technical experiments of these playwrights. One needs to analyze these plays for applied study of Indian socio-political issues. Most of the scholars have neglected these dramatists and have overworked on Rabindranath Tagore, Mohan Rakesh, Vijay Tendulkar, Badal Sircar, and Girish Karnad and recently on Mahesh Dattani. Most studies evolve around the themes in the plays of these playwrights. The significant frame work of marriage and family and their portrayal in these plays hardly received any critical attention of the scholars. 4 Importance of the Research Work Marriage is the most covetous and turning moment in the life of the individuals. It is also an important rite in the Indian culture. It initiates youths to domestic spheres of the life. From societal points of view, it accords a collective social sanction to act of reproduction. It introduces the marrying couple to another equally important social institution called family. Traditionally, family is a distribution and trying the members of the society into groups of the same caste and belief. It also works as a primary centre of imparting samskars on the family members and governs the behavior of its members. Family has always remained as the backdrop of the action in the Indian literature both in print and media (cinema and TV). It has reflected and borne the changes taking place around. Education, socio-political movements, and economic changes have influenced the family as a social institution in India. But there hardly seems any research undertaken on this aspect of Indian drama. -

WOMEN WHO DARED Edited by Ritu Menon (Published by the National Book Trust, New Delhi India, Price Rs 75 Only)

WOMEN WHO DARED Edited by Ritu Menon (Published by the National Book Trust, New Delhi India, Price Rs 75 only) Ammanige (To My Mother) SA USHA Mother, don’t, please don’t Don’t cut off the sunlight With your sari spread across the sky Blanching life’s green leaves Don’t say: you’re seventeen already Don’t flash your sari in the street Don’t make eyes at passers-by Don’t be a tomboy riding the winds Don’t play that tune again That your mother, Her mother and her mother Had played on the snake-charmer’s flute Into the ears of nitwits like me I am just spreading my hood I’ll sink my fangs into someone And leave my venom. Let go, make way. Circumambulating the holy plant In the yard, making rangoli designs To see heaven, turning up dead Without light and air. For God’s sake, I can’t do it. Breaking out of the dam You’ve built, swelling In a thunderstorm Roaring through the land, Let me live very differently From you, mother. Let go, make way. (Tr. A. K. Ramanujan) Introduction For at least a century and a half now, the presence of women in the social and public life of India has been noted, even if they have only been intermittently and sporadically visible, and insufficiently acknowledged. Most people, when asked, will recall women’s participation in the freedom struggle, their mobilisation by the thousands in Gandhiji’s campaigns against the British, in the salt satyagraha, and in the civil disobedience and non-cooperation movements. -

Searching for Shakuntala: Sanskrit Drama and Theatrical Modernity in Europe and India, 1789-Present

SEARCHING FOR SHAKUNTALA: SANSKRIT DRAMA AND THEATRICAL MODERNITY IN EUROPE AND INDIA, 1789-PRESENT AMANDA CULP Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Amanda Culp All rights reserved ABSTRACT Searching for Shakuntala: Sanskrit Drama and Theatrical Modernity in Europe and India, 1789-Present Amanda Culp Since the end of the eighteenth century, the Sanskrit drama known as Shakuntala (Abhijñānaśakuntala) by Kalidasa has held a place of prominence as a classic of world literature. First translated into English by Sir William Jones in 1789, in the intervening centuries Shakuntala has been extolled and memorialized by the likes of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich and August Wilhelm Schlegel, Theophile Gautier, and Rabindranath Tagore. Though often included in anthologies of world literature, however, the history of the play in performance during this same period of time has gone both undocumented and unstudied. In an endeavor to fill this significant void in scholarship, “Searching for Shakuntala” is the first comprehensive study of the performance history of Kalidasa’s Abhijñānaśakuntala in Europe and India. It argues that Shakuntala has been a critical interlocutor for the emergence of modern theater practice, having been regularly featured on both European and Indian stages throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Moreover, it asserts that to appreciate the contributions that the play has made to modern theater history requires thinking through and against the biases and expectations of cultural authenticity that have burdened the play in both performance and reception.