Is There, Or Should There Be, a National Theatre in India?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SIKH TIMES ALL PAGE for WEB.Qxd

@thesikhtimes facebook.com/ instagram.com/ thesikhtimes thesikhtimes VISIT: PUBLISHED FROM Delhi, Haryana, Uttar www.thesikhtimes.in Pradesh, Punjab, The Sikh Times Email:[email protected] Chandigarh, Himachal and Jammu National Daily Vol. 12 No. 219 RNI NO. DELENG/2008/25465 New Delhi, Tuesday, 29 December, 2020 [email protected] 9971359517 12 pages. 2/- Maharashtra home minister asks CBI to reveal findings of SSR Farmers' protest against death case probe Mumbai Maharashtra’s Home Minister Anil Deshmukh on Sunday said the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) should soon clarify whether late actor Sushant Singh agri laws enters day 33 Rajput was murdered or died by suicide. Speaking to members of the media, Deshmukh said, “It has been four months since the probe the protesting farmer was transferred to CBI. People ask me about the conclusion. I think CBI should soon unions had decided to clarify whether it was suicide or murder.” His comment comes months after the CBI was resume their dialogue handed over the investigation into the actor’s death earlier this year. Deshmukh has also with the Centre, and appealed to the agency to reveal findings of the probe in the high-profile case. In July, proposed December 29 almost a month after the actor's death, Deshmukh had said a CBI probe is not for the next round of required in the incident.It may be noted that talks. Simmi Kaur Babbar NEW DELHI: Farmers protest against the three central contentious agricultural laws entered day 33 on Monday (December 28) as the government and farmers' union leaders prepare for the sixth round of talks on Tuesday. -

Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

S T Q Contents SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Issue 17 March 1998 2 EDITORIAL Editor 3 Anjum Katyal ‘UNPEELING THE LAYERS WITHIN YOURSELF ’ Editorial Consultant Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry Samik Bandyopadhyay 22 Project Co-ordinator A GATKA WORKSHOP : A PARTICIPANT ’S REPORT Paramita Banerjee Ramanjit Kaur Design 32 Naveen Kishore THE MYTH BEYOND REALITY : THE THEATRE OF NEELAM MAN SINGH CHOWDHRY Smita Nirula 34 THE NAQQALS : A NOTE 36 ‘THE PERFORMING ARTIST BELONGED TO THE COMMUNITY RATHER THAN THE RELIGION ’ Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry on the Naqqals 45 ‘YOU HAVE TO CHANGE WITH THE CHANGING WORLD ’ The Naqqals of Punjab 58 REVIVING BHADRAK ’S MOGAL TAMSA Sachidananda and Sanatan Mohanty 63 AALKAAP : A POPULAR RURAL PERFORMANCE FORM Arup Biswas Acknowledgements We thank all contributors and interviewees for their photographs. 71 Where not otherwise credited, A DIALOGUE WITH ENGLAND photographs of Neelam Man Singh An interview with Jatinder Verma Chowdhry, The Company and the Naqqals are by Naveen Kishore. 81 THE CHALLENGE OF BINGLISH : ANALYSING Published by Naveen Kishore for MULTICULTURAL PRODUCTIONS The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Jatinder Verma 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 86 MEETING GHOSTS IN ORISSA DOWN GOAN ROADS Printed at Vinayaka Naik Laurens & Co 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Dear friend, Four years ago, we started a theatre journal. It was an experiment. Lots of questions. Would a journal in English work? Who would our readers be? What kind of material would they want?Was there enough interesting and diverse work being done in theatre to sustain a journal, to feed it on an ongoing basis with enough material? Who would write for the journal? How would we collect material that suited the indepth attention we wanted to give the subjects we covered? Alongside the questions were some convictions. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

Robert Lepage's Scenographic Dramaturgy: the Aesthetic Signature at Work

1 Robert Lepage’s Scenographic Dramaturgy: The Aesthetic Signature at Work Melissa Poll Abstract Heir to the écriture scénique introduced by theatre’s modern movement, director Robert Lepage’s scenography is his entry point when re-envisioning an extant text. Due to widespread interest in the Québécois auteur’s devised offerings, however, Lepage’s highly visual interpretations of canonical works remain largely neglected in current scholarship. My paper seeks to address this gap, theorizing Lepage’s approach as a three-pronged ‘scenographic dramaturgy’, composed of historical-spatial mapping, metamorphous space and kinetic bodies. By referencing a range of Lepage’s extant text productions and aligning elements of his work to historical and contemporary models of scenography-driven performance, this project will detail how the three components of Lepage’s scenographic dramaturgy ‘write’ meaning-making performance texts. Historical-Spatial Mapping as the foundation for Lepage’s Scenographic Dramaturgy In itself, Lepage’s reliance on evocative scenography is inline with the aesthetics of various theatre-makers. Examples range from Appia and Craig’s early experiments summoning atmosphere through lighting and minimalist sets to Penny Woolcock’s English National Opera production of John Adams’s Dr. Atomic1 which uses digital projections and film clips to revisit the circumstances leading up to Little Boy’s release on Hiroshima in 1945. Other artists known for a signature visual approach to locating narrative include Simon McBurney, who incorporates digital projections to present Moscow via a Google Maps perspective in Complicité’s The Master and Margarita and auteur Benedict Andrews, whose recent production of Three Sisters sees Chekhov’s heroines stranded on a mound of dirt at the play’s conclusion, an apt metaphor for their dreary futures in provincial Russia. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

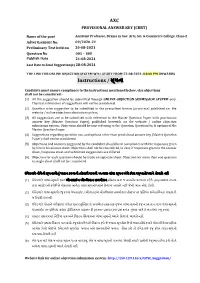

AXC Instructions / ૂચના

AXC PROVISIONAL ANSWER KEY (CBRT) Name of the post Assistant Professor, Drama in Gov. Arts, Sci. & Commerce College, Class-2 Advertisement No. 69/2020-21 Preliminary Test held on 20-08-2021 Question No 001 – 300 Publish Date 21-08-2021 Last Date to Send Suggestion(s) 28-08-2021 THE LINK FOR ONLINE OBJECTION SYSTEM WILL START FROM 22-08-2021; 04:00 PM ONWARDS Instructions / ચનાૂ Candidate must ensure compliance to the instructions mentioned below, else objections shall not be considered: - (1) All the suggestion should be submitted through ONLINE OBJECTION SUBMISSION SYSTEM only. Physical submission of suggestions will not be considered. (2) Question wise suggestion to be submitted in the prescribed format (proforma) published on the website / online objection submission system. (3) All suggestions are to be submitted with reference to the Master Question Paper with provisional answer key (Master Question Paper), published herewith on the website / online objection submission system. Objections should be sent referring to the Question, Question No. & options of the Master Question Paper. (4) Suggestions regarding question nos. and options other than provisional answer key (Master Question Paper) shall not be considered. (5) Objections and answers suggested by the candidate should be in compliance with the responses given by him in his answer sheet. Objections shall not be considered, in case, if responses given in the answer sheet /response sheet and submitted suggestions are differed. (6) Objection for each question should be made on separate sheet. Objection for more than one question in single sheet shall not be considered. ઉમેદવાર નીચેની ૂચનાઓું પાલન કરવાની તકદાર રાખવી, અયથા વાંધા- ૂચન ગે કરલ રૂઆતો યાને લેવાશે નહ (1) ઉમેદવાર વાંધાં- ૂચનો ફત ઓનલાઈન ઓશન સબમીશન સીટમ ારા જ સબમીટ કરવાના રહશે. -

Hkkjr Fodkl Ifj"Kn % Jktlfkku ¼E/;½ Çkur

Hkkjr fodkl ifj"kn~ % jktLFkku ¼e/;½ çkUr Hkkjr dks tkuks çfr;ksfxrk & 2016 ist laå 1 ftyk dksM&02 ftyk&HkhyokM+k 'kk[kk dksM&024 'kk[kk&foosdkuUn ijh{kk dsUnz dksM&0451 dsUnz dk uke&laLdkj fo|k fudsru gehjx<+ Max. Obt. Sr. Candidate Name No. Marks Marks oxZ% dfu"B 1 ABHISHEK GARG 75 27 2 ANKIT SINGH RAJPUT 75 23 3 BRIJESH PRAJAPAT 75 32 4 DEVILAL PR AJAPAT 75 24 5 FIR JO 75 28 6 KISHAN PRAJAPAT 75 18 7 LALIT MALVEE 75 23 8 MUKESH SALVI 75 27 9 NIRU GARG 75 26 10 PAPPU MAIL 75 24 11 RAHUL KHATIK 75 22 12 RATAN PRAJAPAT 75 33 13 RISHABHGARG 75 21 14 SAJANA KHATIK 75 20 15 SALONI GARG 75 32 16 SANAM SALVI 75 33 17 SANDEEP SHANI 75 26 18 SANWAR MALI 75 18 19 SUNIL SALVI 75 19 20 SUNILPRAJAPAT 75 25 21 TASHMEYA TARNOM 75 29 22 VIKAS AHIRWAR 75 32 Hkkjr fodkl ifj"kn~ % jktLFkku ¼e/;½ çkUr Hkkjr dks tkuks çfr;ksfxrk & 2016 ist laå 2 ftyk dksM&02 ftyk&HkhyokM+k 'kk[kk dksM&024 'kk[kk&foosdkuUn ijh{kk dsUnz dksM&0452 dsUnz dk uke&jk-ck-ek-fo- Lo#ixat Max. Obt. Sr. Candidate Name No. Marks Marks oxZ% dfu"B 1 AANCHAL TIWARI 75 3 2 ANJALI DUBEY 75 16 3 ANNU SHARMA 75 32 4 ARTI SUTHAR 75 25 5 BABALE MANSURI 75 29 6 BHAWANA TELI 75 35 7 C HANDA BLLI 75 20 8 DEV KUMARI PRAJAPAT 75 44 9 DIMPLE BOSE 75 42 10 DIVYA TAILOR 75 27 11 HEMALATA SUW LKA 75 11 12 JANA KANWAR 75 18 13 JYOTI REGAR 75 21 14 KASHISH 75 18 15 KINJAL TAILOR 75 23 16 KOMAL LOHAR 75 23 17 KOMAL TAILOR 75 21 18 KRISHNA PRAJAPAT 75 39 19 KUMKU MTAILOR 75 24 20 LAKSHITA SHARMA 75 24 21 LAXMI KEER 75 25 22 MAHIMA GADRI 75 6 23 MAMTA KANWER DAROGA 75 33 24 MAMTA SEN 75 35 25 MUSKAN BANU 75 21 26 NAJEEYAPRAVEN 75 12 27 NIKITAKMEENA 75 26 28 NITU MEGHWAL 75 32 29 PAYAL KANWER 75 28 30 PINKI SALVI 75 23 31 POOJA SUWALKA 75 26 32 POOJA TELI 75 25 33 POOJAOJOSHI 75 20 34 POOJATAILOR 75 25 35 PRITAM KANWAR PURAWAT 75 40 36 PRITI BAIRWA 75 41 37 PRIYANKA DAROGA 75 34 38 PRIYANKA TAILO R 75 42 39 RADHIKA JOSHI 75 40 Hkkjr fodkl ifj"kn~ % jktLFkku ¼e/;½ çkUr Hkkjr dks tkuks çfr;ksfxrk & 2016 ist laå 3 ftyk dksM&02 ftyk&HkhyokM+k 'kk[kk dksM&024 'kk[kk&foosdkuUn ijh{kk dsUnz dksM&0452 dsUnz dk uke&jk-ck-ek-fo- Lo#ixat Max. -

The Poetics of Persian Music

The Poetics of Persian Music: The Intimate Correlation between Prosody and Persian Classical Music by Farzad Amoozegar-Fassie B.A., The University of Toronto, 2008 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2010 © Farzad Amoozegar-Fassie, 2010 Abstract Throughout most historical narratives and descriptions of Persian arts, poetry has had a profound influence on the development and preservation of Persian classical music, in particularly after the emergence of Islam in Iran. A Persian poetic structure consists of two parts: the form (its fundamental rhythmic structure, or prosody) and the content (the message that a poem conveys to its audience, or theme). As the practice of using rhythmic cycles—once prominent in Iran— deteriorated, prosody took its place as the source of rhythmic organization and inspiration. The recognition and reliance on poetry was especially evident amongst Iranian musicians, who by the time of Islamic rule had been banished from the public sphere due to the sinful socio-religious outlook placed on music. As the musicians’ dependency on prosody steadily grew stronger, poetry became the preserver, and, to a great extent, the foundation of Persian music’s oral tradition. While poetry has always been a significant part of any performance of Iranian classical music, little attention has been paid to the vitality of Persian/Arabic prosody as its main rhythmic basis. Poetic prosody is the rhythmic foundation of the Persian repertoire the radif, and as such it makes possible the development, memorization, expansion, and creation of the complex rhythmic and melodic compositions during the art of improvisation. -

Rajit Kapur, Shernaz Patel on Performing 'Love Letters' at Delhi's Old World Theatre Festival

Oct, 08 2017 Rajit Kapur, Shernaz Patel on performing 'Love Letters' at Delhi's Old World Theatre Festival Fifteen plays. Ten days. The 2017 edition of the Old World Theatre Festival (OWTF) that kick-started on 6 October 2017 at the India Habitat Centre, New Delhi, has theatre lovers rejoicing at the return of some of the most prestigious productions on stage. In an exclusive chat with us, veteran thespians Rajit Kapur and Shernaz Patel spoke about one of their longest- running plays — Love Letters (directed by Rahul da Cunha), the relevance of handwritten letters in a digital world, and their memories of working with one of the stalwarts of Indian theatre, Tom Alter. Love At A Click Letters are passé. The ink doesn’t flow freely, and emotions are bunched up in 140 characters or less. Does a play on love letters have any meaning, then? For Rajit Kapur, love letters are precious. “Letters have become a novelty in today’s age. If someone receives a letter, it becomes really special and cherished by the person. The value of a letter has really gone up,” he says. Shernaz Patel too endorses the magic of handwritten letters and says, “I think love letters matter now more than ever. In an age where people make up and break up on SMS, it’s so important to remember the absolute beauty and power of words. We all love receiving cards and notes that we can keep forever... that don’t get erased with the click of a button.” Rajit and Shernaz perform Love Letters Oct, 08 2017 Love Letters Sans Letters AR Gurney’s epistolary play Love Letters, which premiered in 1988, has had several adaptations over the years — Javed Siddiqui’s Tumhari Amrita (starring Shabana Azmi and Farooq Sheikh, directed by Feroz Abbas Khan) being one of the most popular. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations.