Sanjay Joshi 00.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

Patrachar Vidyalaya : Bl Block Shalimar Bagh Delhi-88 Class Xii , Roll Numbers According to Pv Numbers ( 2020-2021)

PATRACHAR VIDYALAYA : BL BLOCK SHALIMAR BAGH DELHI-88 CLASS XII , ROLL NUMBERS ACCORDING TO PV NUMBERS ( 2020-2021) S.No APPLICATION PV NO. ROLL NO STUDENT NAME FATHER NAME 1 PV202012C0410 14614940 Shubham Samanta Manoranjan Samanta 2 PV202012C0092 14614941 Nitesh bansal Anil bansal 3 PV202012C1048 14614942 MANANDEEP SINGH harpal singh 4 PV202012E0359 14614943 JIBIN JOLLY GEORGE JOLLY GEORGE 5 PV202012E0120 14614944 deepanshu kumar rajesh kumar 6 PV202012E0446 14614945 SOUMYA VARGHESE VARGHESE MATHEW 7 PV202012E0139 14614946 PRATIK KARNANI NAND KISHOR KARNANI 8 PV202012C0141 14614947 KRISH KOHLI RATTAN SINGH 9 PV202012C1685 14614948 Madiha asim ali Sayyed asim ali 10 PV202012E0585 14614949 ABHISHEK JAIN SANJAY KUMAR JAIN 11 PV202012E0581 14614950 ISHA JAIN SANJAY KUMAR JAIN 12 PV202012S0105 14614951 Amisha Vinay Kumar 13 PV202012E1341 14614952 AAHIL ALADEEN 14 PV202012C0280 14614953 CHARU PAWAR SHIV NARAYAN 15 PV202012S0162 14614954 Shaun Manjaly Joy Manjaly 16 PV202012S0063 14614955 SIMRAN KAUR SURENDER SINGH 17 PV202012S0317 14614956 AUSTIN JAMES ANIL JAMES 18 PV202012S0347 14614957 DINISHA KAlSAN SUBHASH CHANDER 19 PV202012E0628 14614958 ZAFAR AHMAD ZAHEER AHMAD 20 PV202012S1369 14614959 MANISH SINGH MITHILESH SINGH 21 PV202012E1157 14614960 Anushka Uday Kumar Singh 22 PV202012E0451 14614961 ATISHAY JAIN RAJEEV JAIN 23 PV202012C0498 14614962 BHARAT CH NATH BABUL CH NATH 24 PV202012N0993 14614963 Yash Gupta Neel Kamal Gupta 25 PV202012E1297 14614964 Rachit Saini Tarvinder Saini 26 PV202012E0082 14614965 TIYA MITTRA VINEET MITTRA 27 -

Magazine1-4 Final.Qxd (Page 3)

SUNDAY, JULY 19, 2020 (PAGE 4) What we obtain too cheap, BOLLYWOOD-BUZZ we esteem too lightly Unforgettable Bimal Roy V K Singh Inderjeet S. Bhatia "Prince" Devdass (Dilip Kumar) and Paro's (Suchitra Sen). Child music and song " Yeh mera Diwanapan Hai" by mukesh are hood friendship blossoms into love. But Paro is forced to still popular. 'The harder the conflict, the more glorious The 111th birth anniversary of Bimal Roy, the father fig- marry a rich zamindar because Dev Dass's Father (Murad) "Kabuliwala" produced by Bimal Roy and released on the truimph'. These words of Thomas Paine ure of Indian Cinema was held on 12th was against this relationship. This turned Devdass into a 14th Dec,1961 was not a commercial hit but is still remem- written before the American Revolution July. Bimal Roy, lovingly called as depressed alcoholic. Chandramukhi (Vijayanthimala) too bered for power-packed performace of Balraj Sahni in the Bimal Da 1909 to a Bengali Baidya , sought to inspire Americans in their struggle could not provide solace to his bleeding heart. Released on title role of a Pathan called Rahmat whose wife is no more. Dhaka, which was part of Eastern Jan 1 , 1955 film created box office history by collecting He has a little daughter Ameena (Baby Farida) to whom he for freedom against Great Britain. They have Bengal before partition of 1947 (now more 1 crore in those times. Film bagged best actress in a cares like a mother. He also keep saving her from the wrath an evergreen freshness and resonate with the Dhaka division Bangladesh). -

Unclaimed Dividend Details of 2019-20 Interim

LAURUS LABS LIMITED Dividend UNPAID REGISTER FOR THE YEAR INT. DIV. 2019-20 as on September 30, 2020 Sno Dpid Folio/Clid Name Warrant No Total_Shares Net Amount Address-1 Address-2 Address-3 Address-4 Pincode 1 120339 0000075396 RAKESH MEHTA 400003 1021 1531.50 104, HORIZON VIEW, RAHEJA COMPLEX, J P ROAD, OFF. VERSOVA, ANDHERI (W) MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 400061 2 120289 0000807754 SUMEDHA MILIND SAMANGADKAR 400005 1000 1500.00 4647/240/15 DR GOLWALKAR HOSPITAL PANDHARPUR MAHARASHTRA 413304 3 LLA0000191 MR. RAJENDRA KUMAR SP 400008 2000 3000.00 H.NO.42, SRI VENKATESWARA COLONY, LOTHKUNTA, SECUNDERABAD 500010 500010 4 IN302863 10001219 PADMAJA VATTIKUTI 400009 1012 1518.00 13-1-84/1/505 SWASTIK TOWERS NEAR DON BASCO SCHOOL MOTHI NAGAR HYDERABAD 500018 5 IN302863 10141715 N. SURYANARAYANA 400010 2064 3096.00 C-102 LAND MARK RESIDENCY MADINAGUDA CHANDANAGAR HYDERABAD 500050 6 IN300513 17910263 RAMAMOHAN REDDY BHIMIREDDY 400011 1100 1650.00 PLOT NO 11 1ST VENTURE PRASANTHNAGAR NR JP COLONY MIYAPUR NEAR PRASHANTH NAGAR WATER TANK HYDERABAD ANDHRA PRADESH 500050 7 120223 0000133607 SHAIK RIYAZ BEGUM 400014 1619 2428.50 D NO 614-26 RAYAL CAMPOUND KURNOOL DIST NANDYAL Andhra Pradesh 518502 8 120330 0000025074 RANJIT JAWAHARLAL LUNKAD 400020 35 52.50 B-1,MIDDLE CLASS SOCIETY DAFNALA SHAHIBAUG AHMEDABAD GUJARAT 38004 9 IN300214 11886199 DHEERAJ KOHLI 400021 80 120.00 C 4 E POCKET 8 FLAT NO 36 JANAK PURI DELHI 110058 10 IN300079 10267776 VIJAY KHURANA 400022 500 750.00 B 459 FIRST FLOOR NEW FREINDS COLONY NEW DELHI 110065 11 IN300206 10172692 NARESH KUMAR GUPTA 400023 35 52.50 B-001 MAURYA APARTMENTS 95 I P EXTENSION PATPARGANJ DELHI 110092 12 IN300513 14326302 DANISH BHATNAGAR 400024 100 150.00 67 PRASHANT APPTS PLOT NO 41 I P EXTN PATPARGANJ DELHI 110092 13 IN300888 13517634 KAMNI SAXENA 400025 20 30.00 POCKET I 87C DILSHAD GARDEN DELHI . -

Home >> Archives

Home >> Archives Archives - 2016 Volume 4, issue 4 July - August 2016 Volume 4, Issue 4 - Journal Cover Page Download pdf Validation of A Commercial Hand-Held Human Electronic Glucose Meter for use in 1. Pigs Rosa Elena Pérez Sanchez, Gerardo Ordaz Ochoa, Aureliano Juárez Caratachea, Rafael Maria Román Bravo, Ruy Ortiz Rodriguez Page No: 1-7 Download pdf doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.18782/2320-7051.2364 Instituto de Investigaciones agropecuarias y Forestales-Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. Km 9,5 Carretera Morelia-Zinapécuaro. Tarímbaro Michoacán, México 0 Download : Diatom Species in Lake Batur, Bali Province, Indonesia As Supporting Data for 2. Forensic Analysis of Drowned Victim Ni Made Suartini and I Ketut Junitha Page No: 8-14 Download pdf doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.18782/2320-7051.2363 Biology Department, Faculty of Mathematic and Natural Sciences, Udayana University, Bukit Jimbaran-Badung, Bali-Indonesia 0 Download : Ecological Characterization and Mass propagation of Mansonia altissima A. Chev. in 3. the Guinean Zone of Benin, West Africa Wédjangnon A. Appolinaire, Houètchégnon Towanou and Ouinsavi Christine Page No: 15-25 Download pdf doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.18782/2320-7051.2339 Laboratoire d’Etudes et de Recherches Forestières (LERF), Faculté d’Agronomie, Université de Parakou, Bénin 0 Download : 4. Identification of the Substance Bioactive Leaf Extract Piper caninum Potential as Botanical Pesticides Ni Luh Suriani Page No: 26-32 Download pdf doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.18782/2320-7051.2337 Department of Biology, Faculty of mathematics and Natural Sciences, Udayana University, Kampus Bukit Jimbaran Bali, Indonesia 0 Download : Effect of Cinnamon Leaf Extract Formula (Cinnamomum Burmanni Blume) on 5. -

Understanding Meaningful Cinema

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY– SEPT 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Understanding Meaningful Cinema Dr. Debarati Dhar Assistant Professor, Vivekananda School of Journalism and Mass Communication Vivekananda Institute of Professional Studies, New Delhi. Received: June 23 , 2018 Accepted: August 03, 2018 Introduction: Cinephilia Cineastes say that films help the audience to reflect on the divergent cultures and justify the presence of multi-cultural, multi-ethnic audience in view of this divergence. The language of cinema continues to evolve in a living tradition and the filmmakers trace the ever-changing language of this medium from the silent era to the talkies, from the days when screen went from black and white and got colorized. Emotional appeal, subtlety in its communication and most importantly throwing a new light on the world, as we know it counted a lot to the audience. Filmmakers now work across the spectrum of media including painting, novels, theatre and opera. In the global cinema, in general, the production has become more accessible today, the qualitative aspects have sadly given way to quantity and so, films often miss emotional and spiritual richness. The world is a closer place today. Perhaps it is cinema that helps to blur the boundaries. The concept of film as a commercial art form started in fifties. The fifties and sixties are generally known as the golden period of Indian cinema not only because masterpieces were being made, but because of the popularity of the songs of that era. One of the distinctive features of Indian cinema is its narrative structure. -

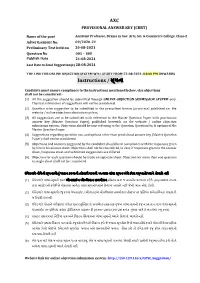

AXC Instructions / ૂચના

AXC PROVISIONAL ANSWER KEY (CBRT) Name of the post Assistant Professor, Drama in Gov. Arts, Sci. & Commerce College, Class-2 Advertisement No. 69/2020-21 Preliminary Test held on 20-08-2021 Question No 001 – 300 Publish Date 21-08-2021 Last Date to Send Suggestion(s) 28-08-2021 THE LINK FOR ONLINE OBJECTION SYSTEM WILL START FROM 22-08-2021; 04:00 PM ONWARDS Instructions / ચનાૂ Candidate must ensure compliance to the instructions mentioned below, else objections shall not be considered: - (1) All the suggestion should be submitted through ONLINE OBJECTION SUBMISSION SYSTEM only. Physical submission of suggestions will not be considered. (2) Question wise suggestion to be submitted in the prescribed format (proforma) published on the website / online objection submission system. (3) All suggestions are to be submitted with reference to the Master Question Paper with provisional answer key (Master Question Paper), published herewith on the website / online objection submission system. Objections should be sent referring to the Question, Question No. & options of the Master Question Paper. (4) Suggestions regarding question nos. and options other than provisional answer key (Master Question Paper) shall not be considered. (5) Objections and answers suggested by the candidate should be in compliance with the responses given by him in his answer sheet. Objections shall not be considered, in case, if responses given in the answer sheet /response sheet and submitted suggestions are differed. (6) Objection for each question should be made on separate sheet. Objection for more than one question in single sheet shall not be considered. ઉમેદવાર નીચેની ૂચનાઓું પાલન કરવાની તકદાર રાખવી, અયથા વાંધા- ૂચન ગે કરલ રૂઆતો યાને લેવાશે નહ (1) ઉમેદવાર વાંધાં- ૂચનો ફત ઓનલાઈન ઓશન સબમીશન સીટમ ારા જ સબમીટ કરવાના રહશે. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

R[`C Cv[ZX >`UZ¶D W`Tfd ` H`^V

( E8 F F F ,./0,1 234 #)#)* .#,/0 +#,- < 8425?O#$192##618 46$8$+2#$218?7.2123*7$#2 6+@218$16+2694 234$3)9(17 5476354)5612# 6+ +6194$+6$)+ 9461$@6+4 72#$1#7)84$1$6 6##6##$16826847*2 9766*2+$96<$163 24+6)1 4>2+656.$?6> 66 39 )+* " ,,- & G6 # 2 6 ! %% 2# # 5 46 R! #$ O P R 12 234$ ment issue during the Covid 12 234$ sacrifice anyone to meet his Pradesh gets seven Ministers, era and gave enough fodder to 12 234$ the pandemic. Apart from political and governance objec- including Annupriya Patel of n dropping four top level the foreign media to inflict health, Dr Vardhan also held n a major Cabinet overhaul, tives. Aapna Dal (S), an NDA ally IUnion Ministers — Ravi heavy damage on the Modi e was always at the front- two Ministries — science and Iseen as a mid-term appraisal Despite the slogans of and Gujarat has five represen- Shankar Prasad, Prakash Government . Hline shielding the Modi led technology and earth sciences. of his Ministers and resetting “sabka sath sabka vikash,” the tations in the council of Javadekar, Harsh Vardhan, " The others axed a couple of Government’s Covid-19 man- The resignation is seen by Government’s profile post- Cabinet reshuffle has been Ministers. Karnataka is up by Ramesh Pokhriyal “Nishank” ! # hours before the oath-taking agement and Covid-19 vacci- the Government’s critics as an Covid-19 for the next three- based on caste consideration at four Ministers which includes and eight other Ministers — ceremony of new inductions, nation policy, but it did not admission that the pandemic year term, the Prime Minister every level. -

Roll Number of Eligible Candidates for the Post of Process Server(S). Examination Will Be Held on 23Rd February, 2014 at 02.00 P.M

Page 1 Roll Number of eligible Candidates for the post of Process Server(s). Examination will be held on 23rd February, 2014 at 02.00 P.M. to 03.30 P.M (MCQ) and thereafter written test will be conducted at 04.00 P.M. to 05.00 PM in the respective examination centre(s). List of examination centre(s) have already been uploaded on the website of HP High Court, separetely. Name of the Roll No. Fathers/Hus. Name & Correspondence Address Applicant 1 2 3 2001 Ravi Kumar S/O Prem Chand, V.P.O. Indpur Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 176401 S/O Bishan Dass, Vill Androoni Damtal P.O.Damtal Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 2002 Parveen Kumar 176403 2003 Anish Thakur S/O Churu Ram, V.P.O. Baleer Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra-176403 2004 Ajay Kumar S/O Ishwar Dass, V.P.O. Damtal Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra-176403 S/O Yash Pal, Vill. Bain- Attarian P.O. Kandrori Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 2005 Jatinder Kumar 176402 2006 Ankush Kumar S/O Dinesh Kumar, V.P.O. Bhapoo Tehsil Indora, Distt. Kangra-176401 2007 Ranjan S/O Buta Singh,Vill Bari P.O. Kandrori Tehsil Indora , Distt.Kangra-176402 2008 Sandeep Singh S/O Gandharv Singh, V.P.O. Rajakhasa Tehsil Indora, Distt. Kangra-176402 S/O Balwinder Singh, Vill Nadoun P.O. Chanour Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 2009 Sunder Singh 176401 2010 Jasvinder S/O Jaswant Singh,Vill Toki P.O. Chhanni Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra-176403 S/O Sh. Jarnail Singh, R/O Village Amran, Po Tipri, Tehsil Jaswan, Distt. -

Tumhein Dil Se Kaise Juda Hum Karain Gay Mp3 Download

Tumhein dil se kaise juda hum karain gay mp3 download CLICK TO DOWNLOAD · Tumhein Dil Se Kaise Juda Hum Karenge Full Song _ Doodh Ka Karz _ Jackie Shroff, Neelam. pitersondavid. Tumhein Hum Bahut Pyar. Honest Liar. Tumhein Hum Bahut Pyar. Punjabi Meego. Hum Aise karenge pyar - Jaan. Bolly HD renuzap.podarokideal.ru Tumhein dillagi bhool jani pare gi Muhabbat ki raahon mein aa kar to dekho Tarapne pe mere na phir tum hanso ge Tarapne pe mere na phir tum hanso ge Kabhi dil kissi se laga kar to dekho Honton ke paas aye hansi, kya majaal hai Dil ka muamla hai koi dillagi nahin Zakhm pe zakhm kha ke ji Apne lahoo ke ghont pi Aah na kar labon ko si Ishq hai renuzap.podarokideal.ru+tumhe+dillagi+bhool. Mere Dil Ko Tere Dil Ki Mp3 Downloadrenuzap.podarokideal.ru Explore Trending Bollywood hits back to back featuring Guru Randhawa, Arijit Singh, Mohit Chauhan, Zubin Nautiyal & many more. Our algorithm automatically provides quality content to explore based on your likes. CatchItFirst!renuzap.podarokideal.ru A site about ziaraat of Muslim religious sites with details, pictures, nohas, majalis and renuzap.podarokideal.ru Kaise kare online business kamayi internet youtube se paise kaise kamaye youtube se song video kaise download upload kare ladki se dosti, ladki ko propose impress Pyar ka izhar kaise kare friendship, bridal makeup kaise kare exam ki taiyari study renuzap.podarokideal.ru · Download Koi Apna Nahi Mp3 Mp3 Sound. Nikala Nahi Jata Kisi Ko Dil Se Shab - Love Motivational Whatsapp Status Video Status Video Song Free Download, Nikala Nahi