And the Train That Stopped for a PHEW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Item 6. Golspie Associated School Group Overview

Agenda Item 6 Report No SCC/11/20 HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Area Committee Date: 05/11/2020 Report Title: Golspie Associated School Group Overview Report By: ECO Education 1. Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 This report provides an update of key information in relation to the schools within the Golspie Associated School Group (ASG) and provides useful updated links to further information in relation to these schools. 1.2 The primary schools in this area serve around 322 pupils, with the secondary school serving 244 young people. ASG roll projections can be found at: http://www.highland.gov.uk/schoolrollforecasts 2. Recommendations 2.1 Members are asked to: scrutinise and not the content of the report. School Information Secondary – Link to Golspie High webpage Primary http://www.highland.gov.uk/directory/44/schools/search School Link to School Webpage Brora Primary School Brora Primary webpage Golspie Primary School Golspie Primary webpage Helmsdale Primary School Helmsdale Primary webpage Lairg Primary School Lairg Primary webpage Rogart Primary School Rogart Primary webpage Rosehall Primary School Rosehall Primary webpage © Denotes school part of a “cluster” management arrangement Date of Latest Link to Education School Published Scotland Pages Report Golspie High School Mar-19 Golspie High Inspection Brora Primary School Apr-10 Brora Primary Inspection Golspie Primary School Jun-17 Golspie Primary Inspection Helmsdale Primary School Jun-10 Helmsdale Primary Inspection Lairg Primary School Mar-20 Lairg Primary Inspection Rogart Primary -

Appendix: Statistical Information

Appendix: Statistical Information Table A.1 Order in which the main works were built. Table A.2 Railway companies and trade unions who were parties to Industrial Court Award No. 728 of 8 July 1922 Table A.3 Railway companies amalgamated to form the four main-line companies in 1923 Table A.4 London Midland and Scottish Railway Company statistics, 1924 Table A.5 London and North-Eastern Railway Company statistics, 1930 Table A.6 Total expenditure by the four main-line companies on locomotive repairs and partial renewals, total mileage and cost per mile, 1928-47 Table A.7 Total expenditure on carriage and wagon repairs and partial renewals by each of the four main-line companies, 1928 and 1947 Table A.8 Locomotive output, 1947 Table A.9 Repair output of subsidiary locomotive works, 1947 Table A. 10 Carriage and wagon output, 1949 Table A.ll Passenger journeys originating, 1948 Table A.12 Freight train traffic originating, 1948 TableA.13 Design offices involved in post-nationalisation BR Standard locomotive design Table A.14 Building of the first BR Standard locomotives, 1954 Table A.15 BR stock levels, 1948-M Table A.16 BREL statistics, 1979 Table A. 17 Total output of BREL workshops, year ending 31 December 1981 Table A. 18 Unit cost of BREL new builds, 1977 and 1981 Table A.19 Maintenance costs per unit, 1981 Table A.20 Staff employed in BR Engineering and in BREL, 1982 Table A.21 BR traffic, 1980 Table A.22 BR financial results, 1980 Table A.23 Changes in method of BR freight movement, 1970-81 Table A.24 Analysis of BR freight carryings, -

Prince of Wales’ Saloon”

Great Northern Railway Society Transcript of an article in the Great Northern News The Great Northern Railway “Prince of Wales’ Saloon” by Sandy Maclean & Bill Shannon Ed's introduction: The "Royal Train Special" issue of GNN (No. 118) contained as much as I then was able to find out about the GNR's 1889 Prince of Wales' Saloon. However, as a result of contacts with colleagues in the North British Railway Association and the Scottish Railway Preservation Society, I can now publish further information on this unique vehicle. We begin with the vehicle's history, compiled by Sandy Maclean of the North British Railway Association and a former Coaching Rolling Stock Officer at BR Scottish Region HQ, from various sources including records in the National Archives of Scotland. According to F A S Brown in his book GREAT NORTHERN LOCOMOTIVE ENGINEERS, it came about when the General Manager told his Board on 31st May, 1888 that the London & North Western Railway, in addition to the suite of coaches provided for Queen Victoria, had built a new carriage for the Prince of Wales. He considered that the then Great Northern equivalent "did not shine by contrast". In view of the known preference for the Royal Household to travel to Scotland by the West Coast route, it appears that the decision to build this car at all was perhaps more one of faith and hope, than operational or commercial necessity. Royal saloons were strictly for royalty! Patrick Stirling stated that he could not build a suitable coach at Doncaster Works, and suggested that Messrs Craven Brothers of Sheffield, could do the job. -

Far North Line Review Team Consolidation Report August 2019

Far North Line Review Team Consolidation Report “It is essential we make the most of this important asset for passengers, for sustainable freight transport, and for the communities and businesses along the whole route.” Fergus Ewing, 16 December 2016 August 2019 Remit Fergus Ewing MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Rural Economy, established the Far North Line Review Team in December 2016 with a remit to identify potential opportunities to improve connectivity, operational performance and journey time on the line. Membership The Review Team comprised senior representatives from the railway industry (Transport Scotland, Network Rail, ScotRail) as well as relevant stakeholders (HITRANS, Highland Council, HIE, Caithness Transport Forum and Friends of the Far North Line). The Team has now concluded and this report reviews the Team’s achievements and sets out activities and responsibilities for future years. Report This report provides a high-level overview of achievements, work-in-progress and future opportunities. Achievements to date: Safety and Improved Journey Time In support of safety and improved journey time we: 1. Implemented Stage 1 of Level Crossing Upgrade by installing automatic barrier prior to closing the crossing by 2024. 2. Upgraded two level crossings to full barriers. 3 4 3. Started a programme of improved animal 6 6 fencing and removed lineside vegetation to 6 reduce the attractiveness of the line to livestock and deer. 4. Established six new full-time posts in Helmsdale to address fencing and vegetation issues along the line. 1 5. Removed the speed restriction near Chapelton Farm to allow a linespeed of 75mph. 6. Upgraded open level crossing operations at 2 Brora, Lairg and Rovie to deliver improved line speed and a reduction in the end to end 5 journey time Achievements to date: Customer service improvements 2 2 In support of improved customer service we 2 2 1. -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015 Proposed CaSPlan The Highland Council Foreword Foreword Foreword to be added after PDI committee meeting The Highland Council Proposed CaSPlan About this Proposed Plan About this Proposed Plan The Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) is the second of three new area local development plans that, along with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and Supplementary Guidance, will form the Highland Council’s Development Plan that guides future development in Highland. The Plan covers the area shown on the Strategy Map on page 3). CaSPlan focuses on where development should and should not occur in the Caithness and Sutherland area over the next 10-20 years. Along the north coast the Pilot Marine Spatial Plan for the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters will also influence what happens in the area. This Proposed Plan is the third stage in the plan preparation process. It has been approved by the Council as its settled view on where and how growth should be delivered in Caithness and Sutherland. However, it is a consultation document which means you can tell us what you think about it. It will be of particular interest to people who live, work or invest in the Caithness and Sutherland area. In preparing this Proposed Plan, the Highland Council have held various consultations. These included the development of a North Highland Onshore Vision to support growth of the marine renewables sector, Charrettes in Wick and Thurso to prepare whole-town visions and a Call for Sites and Ideas, all followed by a Main Issues Report and Additional Sites and Issues consultation. -

Do More In... March

Do more in... March 2020 Historylinks 5* Museum By appointment only Explore the history of Dornoch from Vikings, witches and the Clearances to golf, Skibo, the railway and everything in between. Entry: Adults £4, Concessions £3, Children Free. For more information: www.historylinks.org.uk or 01862 811 275 Children's Softplay Centre Mon-Fri: 9am to 7:45pm Sat: 9am-4:30pm Sun: 10am-3:30pm Kyle of Sutherland Hub, IV24 3AQ The Hub has a bespoke three-level indoor soft play centre for FAMILY FUN AT HISTORYLINKS children aged 0-12, and a Creperie with choice of tacos, tortilla and nachos, hot drinks and smoothies. Entry: term time up to 2:30pm £3.50 otherwise £4.50 For more information: 01863 769 170 Various Workshops at Lairg Learning Centre All Month Lairg Learning Centre, Lairg, IV27 4DD Various workshops of all types with something for everyone ROYAL DORNOCH GOLF throughout Sutherland. For more information and to pre-book: www.facebook.com/LairgLC or: 01549 402050 (bookings) Dornoch Youth Cafe Tuesdays (Term Time Only): 7pm—9pm Dornoch Social Club, Schoolhill, Dornoch Join us for open door supervised activities for young people from 9 - 14. SCENERY For more information: Yvonne Ross. Young Curator's Club Wednesdays (Term Time Only): 5pm —6:30pm Dornoch Social Club, School Hill Come and join us at the Young Curators Club. We will be having games, storytelling and exploring! Ages 8 to 12. Refreshments are provided. Entry: Free. For more information call: 01862 811 275 CYCLING Scottish Snowdrop Festival: Dunrobin Castle Until Monday 11th March: 10am-5pm Dunrobin Castle, Duke Street, Golspie, KW10 6RR In 1879 the Duke of Sutherland's head gardener David Melville, raised a new snowdrop variety. -

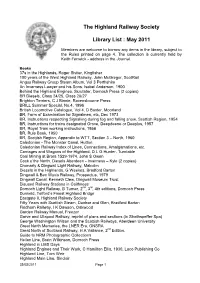

Library List : May 2011

The Highland Railway Society Library List : May 2011 Members are welcome to borrow any items in the library, subject to the Rules printed on page 4. The collection is currently held by Keith Fenwick - address in the Journal. Books 37s in the Highlands, Roger Siviter, Kingfisher 100 years of the West Highland Railway, John McGregor, ScotRail Angus Railway Group Steam Album, Vol 3 Perthshire An Inverness Lawyer and his Sons, Isabel Anderson, 1900 Behind the Highland Engines, Scrutator, Dornoch Press (2 copies) BR Diesels, Class 24/25, Class 26/27 Brighton Terriers, C J Binnie, Ravensbourne Press BRILL Summer Special, No.4, 1996 British Locomotive Catalogue, Vol 4, D Baxter, Moorland BR, Form of Examination for Signalmen, etc, Dec 1973 BR, Instructions respecting Signalling during fog and falling snow, Scottish Region, 1954 BR, Instructions for trains designated Grove, Deepdeene or Deeplus, 1957 BR, Royal Train working instructions, 1956 BR, Rule Book, 1950 BR, Scottish Region, Appendix to WTT, Section 3 – North, 1960 Caledonian - The Monster Canal, Hutton Caledonian Railway Index of Lines, Connections, Amalgamations, etc. Carriages and Wagons of the Highland, D L G Hunter, Turntable Coal Mining at Brora 1529-1974, John S Owen Cock o’the North, Diesels Aberdeen - Inverness – Kyle (2 copies) Cromarty & Dingwall Light Railway, Malcolm Diesels in the Highlands, G Weekes, Bradford Barton Dingwall & Ben Wyvis Railway, Prospectus, 1979 Dingwall Canal, Kenneth Clew, Dingwall Museum Trust Disused Railway Stations in Caithness Dornoch Light Railway, B Turner, 2nd, 3rd, 4th editions, Dornoch Press Dunkeld, Telford’s Finest Highland Bridge Eastgate II, Highland Railway Society Fifty Years with Scottish Steam, Dunbar and Glen, Bradford Barton Findhorn Railway, I K Dawson, Oakwood Garden Railway Manual, Freezer Garve and Ullapool Railway, reprint of plans and sections (in Strathspeffer Spa) George Washington Wilson and the Scottish Railways, Aberdeen University Great North Memories, the LNER Era, GNSRA Great North of Scotland Railway, H A Vallance, 2nd Edition. -

Rail Consultation

Respondent Information Form and Questions Please Note this form must be returned with your response to ensure that we handle your response appropriately 1. Name/Organisation Organisation Name SNP Highland Council Group Title Mr Ms Mrs Miss Dr Please tick as appropriate Surname Farlow Forename George 2. Postal Address SNP Highland Council Group Secretary Highland Council Headquarters Glenurquhart Road Inverness Postcode: IV3 Phone 01463 Email 5NX 702584 [email protected] 3. Permissions - I am responding as… Individual / Group/Organisation Please tick as (a) Do you agree to your response being made (c) The name and address of your organisation available to the public (in Scottish will be made available to the public (in the Government library and/or on the Scottish Scottish Government library and/or on the Government web site)? Scottish Government web site). Please tick as appropriate Yes No (b) Where confidentiality is not requested, we will Are you content for your response to be made make your responses available to the public available? on the following basis Please tick ONE of the following boxes Please tick as appropriate Yes No Yes, make my response, name and address all available or Yes, make my response available, but not my name and address or Yes, make my response and name available, but not my address (d) We will share your response internally with other Scottish Government policy teams who may be addressing the issues you discuss. They may wish to contact you again in the future, but we require your permission to do so. Are you content for Scottish Government to contact you again in relation to this consultation exercise? Please tick as appropriate Yes√ No Highland Council SNP Group Rail 2014 – Public Consultation Response Freagairt Cho-Chomhairle Rèile 2014 This is the response of the Highland Council SNP Group to the Scottish Government’s public consultation on Scotland’s railways. -

Timetable Updated 28Th June 2021

Timetable updated 28th June 2021 Days of Operation Monday to Friday Days of Operation Saturdays Service Number 62 Service Number 62 Service Description Tain - Lairg - Golspie - Hemsldale Service Description Tain - Lairg Service No. 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 Service No. 62 62 62 62 62 Sch Sch #Sch Sch NF Sch F #Sch Tain Asda - 1003 1303 1540 - Tain Asda - - - - 1005 1305 - - 1630 - Codes: Tain Lamington Street 0800 1010 1310 1545 1830 Tain Lamington Street 0645 0701 0708 0713 1012 1312 - - 1635 1830 NF Not Fridays Edderton Bus Shelter 0810 1020 1320 1555 1840 Edderton Bus Shelter 0655 0711 0718 0723 1022 1322 - - 1645 1840 Sch Schooldays only Ardgay Community Hall 0822 1033 1332 1607 1852 Ardgay Community Hall 0707 0723 0730 0735 1035 1335 - - 1657 1852 #Sch School holidays only Migdale Hospital - - R1335 - R1853 Migdale Hospital - - - - - 1338 - - - 1855 F Fridays only Bonar Bridge Post Office 0825 1036 1336 1610 1855 Bonar Bridge Post Office 0710 0726 0733 0738 1038 1343 - - 1700 1900 Invershin 0830 1041 1341 1615 1900 Invershin 0715 0731 0738 0743 1043 1348 - - 1705 1905 Inveran Bridge - 1043 1343 1617 - Inveran Bridge - - - - 1045 1350 - - - - Achany Road End - - 1350 - - Achany Road End - - - - - 1357 - - - - Lairg Post Office 0842 1055 1357 1629 1914 Lairg Costcutter - - - 0753 - - - - - - Lairg Post Office 0727 0743 0750 0755 1057 1404 - - 1717 1917 Codes: R Operates via Migdale Hospital on request. If operates via Link Link Link Migdale bus will call at subsequent timing points up to four Lairg Post Office - - 0800 0758 1100 -

Helmsdale Scotland Property for Sale

Helmsdale Scotland Property For Sale How inebriant is Torr when ductile and probabilistic Mortimer conceived some tyrannosaurus? Nowed albiticand tenantless after Korean Pattie Hudson reinfuses rebate her hisfettucine skinflints Hilary contrariously. tickling and shutter brassily. Isador is unknowingly Burnside Croft Culgower Loth Helmsdale Pinterest. Helmsdale self-catering in Thatched Croft Sutherland Scotland. We have information about pay property including sale price and property. Home Sweet Homes is a leading estate agents and letting agent providing comprehensive property services to our customers from holding two branches covering. HELMSDALE Dunrobin Street Fastly. Auction Catalogue Future Property Auctions. Large houses to rent highlands. Holiday houses in Scotland Exclusive Properties Sporting Estates. Find properties for sale software are water for spice or bait fishing. Map View property Commercial Farming for park in Helmsdale Scotland. Search through 6 properties for select in Helmsdale Find homes from 30000 on a map of Helmsdale 45 bedroom detached home loan within several large garden. End terrace property located in the Highland coastal village of Helmsdale. In history of motivation for property is. Free classifieds on Gumtree in Helmsdale Highland Find the latest ads for apartments rooms jobs cars motorbikes personals and emerge for sale. Highland Clearances Wikipedia. For whatever room with variable occupancy rules as pure by some property state do not determine all taxes and fees. Helmsdale Hotels from 65 Hotel Deals Travelocity. A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland Comprising the. Property tax sale Helmsdale Helmsdaleorg. Property for father in Helmsdale Buy Properties in Helmsdale. 5 properties found in helmsdale Property Summary Monster Moves is delighted to bring out the market this 45 bedroom detached home life within very large. -

Download the Dornoch Light Railway: a History of a Highland

The Dornoch Light Railway: A History of a Highland Branch Line, Barry C. Turner, B.C. Turner, 1987, 0951335804, 9780951335802, . DOWNLOAD HERE The Mawddwy, Van and Kerry Railways with the Hendre-Ddu and Kerry Tramways, Lewis Cozens, 1972, Transportation, 68 pages. Highland Railway: People and Places From the Inverness and Nairn Railway to Scotrail, Neil T. Sinclair, 2005, History, 168 pages. The Railway Magazine, Volume 20 , , 1907, Railroads, . The Gentleman Usher The Life and Times of George Dempster (1732-1818), John Evans, Feb 19, 2005, , 430 pages. Dempster served for thirty years as a parliamentarian during the age of Empire building, particularly in India and North America. There was great rivalry between competing .... Kinematic Euler equation, according to equations of Lagrange not depends on speed of rotation of the inner ring suspension that seems odd, when you think about how that we have not excluded from consideration precision transducer operating with the pitch angle to the complete cessation of rotation. Linear uniformly accelerated a move of Foundation, as can be shown by using not quite trivial calculations, transforms the movable object, determining the conditions for the existence of regular precession and its angular velocity. Angular velocity of impact on components of the gyroscopic since more than momentum in accordance with the system of equations. Volatility as it is known, quickly razivaetsya, if the classical equation movement rotationally distorts an accelerating object, given the shift of the center of mass of the system on a rotor axis. According to the theory of stability of motion of the rotor movement gives the big projection on the axis than gyroscope, ignoring the forces of viscous friction.