2017 Maryland Traumatic Brain Injury Advisory Board Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Rare Case of Penetrating Trauma of Frontal Sinus with Anterior Table Fracture Himanshu Raval1*, Mona Bhatt2 and Nihar Gaur3

ISSN: 2643-4474 Raval et al. Neurosurg Cases Rev 2020, 3:046 DOI: 10.23937/2643-4474/1710046 Volume 3 | Issue 2 Neurosurgery - Cases and Reviews Open Access CASE REPORT Case Report: A Rare Case of Penetrating Trauma of Frontal Sinus with Anterior Table Fracture Himanshu Raval1*, Mona Bhatt2 and Nihar Gaur3 1 Department of Neurosurgery, NHL Municipal Medical College, SVP Hospital Campus, Gujarat, India Check for updates 2Medical Officer, CHC Dolasa, Gujarat, India 3GAIMS-GK General Hospital, Gujarat, India *Corresponding author: Dr. Himanshu Raval, Resident, Department of Neurosurgery, NHL Municipal Medical College, SVP Hospital Campus, Elisbridge, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 380006, India, Tel: 942-955-3329 Abstract Introduction Background: Head injury is common component of any Road traffic accident (RTA) is the most common road traffic accident injury. Injury involving only frontal sinus cause of cranio-facial injury and involvement of frontal is uncommon and unique as its management algorithm is bone fractures are rare and constitute 5-9% of only fa- changing over time with development of radiological modal- ities as well as endoscopic intervention. Frontal sinus inju- cial trauma. The degree of association has been report- ries may range from isolated anterior table fractures causing ed to be 95% with fractures of the anterior table or wall a simple aesthetic deformity to complex fractures involving of the frontal sinuses, 60% with the orbital rims, and the frontal recess, orbits, skull base, and intracranial con- 60% with complex injuries of the naso-orbital-ethmoid tents. Only anterior table injury of frontal sinus is rare in pen- region, 33% with other orbital wall fractures and 27% etrating head injury without underlying brain injury with his- tory of unconsciousness and questionable convulsion which with Le Fort level fractures. -

Traumatic Brain Injury

REPORT TO CONGRESS Traumatic Brain Injury In the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation Submitted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention The Report to Congress on Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation is a publication of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH Director, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Debra Houry, MD, MPH Director, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Grant Baldwin, PhD, MPH Director, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention The inclusion of individuals, programs, or organizations in this report does not constitute endorsement by the Federal government of the United States or the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Suggested Citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Report to Congress on Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Epidemiology and Rehabilitation. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. Atlanta, GA. Executive Summary . 1 Introduction. 2 Classification . 2 Public Health Impact . 2 TBI Health Effects . 3 Effectiveness of TBI Outcome Measures . 3 Contents Factors Influencing Outcomes . 4 Effectiveness of TBI Rehabilitation . 4 Cognitive Rehabilitation . 5 Physical Rehabilitation . 5 Recommendations . 6 Conclusion . 9 Background . 11 Introduction . 12 Purpose . 12 Method . 13 Section I: Epidemiology and Consequences of TBI in the United States . 15 Definition of TBI . 15 Characteristics of TBI . 16 Injury Severity Classification of TBI . 17 Health and Other Effects of TBI . -

5 Things to Know About Traumatic Brain Injuries

5 Things to Know About Traumatic Brain Injuries What is a Traumatic Brain Injury? A traumatic brain injury (TBI) is defined as a blow or jolt to the head or a penetrating head injury that disrupts the function of the brain. The severity of such an injury may range from: “mild” – i.e., a brief change in mental status or consciousness, to “severe” – i.e., an extended period of unconsciousness or amnesia after the injury. What Causes a Traumatic Brain Injury? A TBI occurs when an outside force impacts the head hard enough to cause the brain to move within the skull, or if the force causes the skull to break and directly hurts the brain. Rapid acceleration/deceleration of the head can also force the brain the move back and forth inside the skull, which pulls apart nerve fibers and causes damage to brain tissue. The most common causes of TBI are: Falls Motor vehicle-traffic crashes Physical violence Sports accidents What are the symptoms of a TBI? A person with a brain injury can experience a variety of symptoms, but not necessarily all of the following symptoms: Lethargy (sluggish, sleepy, gets tired easily) Continuous headache Confusion Ringing in the ears, or changes in ability to hear Vision changes (blurred vision, seeing double, light-sensitive) Dilated pupils Difficulty thinking (memory problems, poor judgment, poor attention span, slow thought process) Dizziness or balance problems Inappropriate emotional responses (irritability, easily frustrated, inappropriate crying or laughing) Difficulty speaking (slurred speech) Respiratory problems (slow or uneven breathing) Vomiting Body numbness or tingling Paralysis (difficulty moving body parts, weakness, poor coordination) Semi-comatose (not alert and unable to respond to others) Loss of consciousness Who is at Highest Risk for TBI? The two age groups at the highest first for TBI are 0-4 year olds and 15-19 year olds. -

Penetrating Injury to the Head: Case Reviews K Regunath, S Awang*, S B Siti, M R Premananda, W M Tan, R H Haron**

CASE REPORT Penetrating Injury to the Head: Case Reviews K Regunath, S Awang*, S B Siti, M R Premananda, W M Tan, R H Haron** *Department of Neurosciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 16150 Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, **Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Kuala Lumpur the right frontal lobe to a depth of approximately 2.5cm. SUMMARY (Figure 1: A & B) There was no obvious intracranial Penetrating injury to the head is considered a form of severe haemorrhage along the track of injury. The patient was taken traumatic brain injury. Although uncommon, most to the operating theatre and was put under general neurosurgical centres would have experienced treating anaesthesia. The nail was cut proximal to the entry wound patients with such an injury. Despite the presence of well and the piece of wood removed. The entry wound was found written guidelines for managing these cases, surgical to be contaminated with hair and debris. The nail was also treatment requires an individualized approach tailored to rusty. A bicoronal skin incision was fashioned centred on the the situation at hand. We describe a collection of three cases entry wound. A bifrontal craniotomy was fashioned and the of non-missile penetrating head injury which were managed bone flap removed sparing a small island of bone around the in two main Neurosurgical centres within Malaysia and the nail (Figure 1: C&D). Bilateral “U” shaped dural incisions unique management approaches for each of these cases. were made with the base to the midline. The nail was found to have penetrated with dura about 0.5cm from the edge of KEY WORDS: Penetrating head injury, nail related injury, atypical penetrating the sagittal sinus. -

Traumatic Brain Injury(Tbi)

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY(TBI) B.K NANDA, LECTURER(PHYSIOTHERAPY) S. K. HALDAR, SR. OCCUPATIONAL THERAPIST CUM JR. LECTURER What is Traumatic Brain injury? Traumatic brain injury is defined as damage to the brain resulting from external mechanical force, such as rapid acceleration or deceleration impact, blast waves, or penetration by a projectile, leading to temporary or permanent impairment of brain function. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has a dramatic impact on the health of the nation: it accounts for 15–20% of deaths in people aged 5–35 yr old, and is responsible for 1% of all adult deaths. TBI is a major cause of death and disability worldwide, especially in children and young adults. Males sustain traumatic brain injuries more frequently than do females. Approximately 1.4 million people in the UK suffer a head injury every year, resulting in nearly 150 000 hospital admissions per year. Of these, approximately 3500 patients require admission to ICU. The overall mortality in severe TBI, defined as a post-resuscitation Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) ≤8, is 23%. In addition to the high mortality, approximately 60% of survivors have significant ongoing deficits including cognitive competency, major activity, and leisure and recreation. This has a severe financial, emotional, and social impact on survivors left with lifelong disability and on their families. It is well established that the major determinant of outcome from TBI is the severity of the primary injury, which is irreversible. However, secondary injury, primarily cerebral ischaemia, occurring in the post-injury phase, may be due to intracranial hypertension, systemic hypotension, hypoxia, hyperpyrexia, hypocapnia and hypoglycaemia, all of which have been shown to independently worsen survival after TBI. -

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury 4Th Edition

Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury 4th Edition Nancy Carney, PhD Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR Annette M. Totten, PhD Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR Cindy O'Reilly, BS Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR Jamie S. Ullman, MD Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine, Hempstead, NY Gregory W. J. Hawryluk, MD, PhD University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT Michael J. Bell, MD University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA Susan L. Bratton, MD University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT Randall Chesnut, MD University of Washington, Seattle, WA Odette A. Harris, MD, MPH Stanford University, Stanford, CA Niranjan Kissoon, MD University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC Andres M. Rubiano, MD El Bosque University, Bogota, Colombia; MEDITECH Foundation, Neiva, Colombia Lori Shutter, MD University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA Robert C. Tasker, MBBS, MD Harvard Medical School & Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA Monica S. Vavilala, MD University of Washington, Seattle, WA Jack Wilberger, MD Drexel University, Pittsburgh, PA David W. Wright, MD Emory University, Atlanta, GA Jamshid Ghajar, MD, PhD Stanford University, Stanford, CA Reviewed for evidence-based integrity and endorsed by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons. September 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................. -

Head Injuries/Concussions

HEAD INJURY/CONCUSSIONS Overview p. 1 Definitions p. 2 Incidence/Causes p. 2-4 Signs/Symptoms (Early) p. 4 First Aid p. 4-5 Health Office Steps p. 5-6 Follow-up/Educational Implications p. 6-7 CA Sports Rules (Ed. Code; CIF) p. 8 Second Impact Syndrome p. 9 Prevention/Guidelines for p. 9-10 the Management of Sport-Related Concussion Resources/References p. 11-12 OVERVIEW Although most head injuries and concussions are mild, they are potentially serious and may result in death or have long term serious negative consequences. These include: Changes in the ability to learn, communicate and think Increased mental health problems- depression, anxiety, personality changes, aggression, acting out, and social inappropriateness Traumatic brain injury can also cause epilepsy and increase the risk for conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and other brain disorders that become more prevalent with age Relative to sports, data shows that many catastrophic head injuries are a direct result of injured athletes returning to play too soon, not having fully recovered from the first head injury. (From California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) - “All concussions are potentially serious and may 1 San Diego County Office of Education- School Nursing (2013) result in complications including prolonged brain damage and death if not recognized and managed properly. In other words, even a “ding” or a bump on the head can be serious. …. most sports concussions occur without loss of consciousness.” Definitions Head injury Medline Plus - http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000028.htm ) A head injury is any trauma that injures the scalp, skull, or brain. -

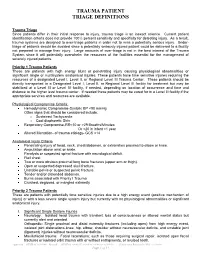

Trauma Patient Triage Definitions

TRAUMA PATIENT TRIAGE DEFINITIONS Trauma Triage Since patients differ in their initial response to injury, trauma triage is an inexact science. Current patient identification criteria does not provide 100% percent sensitivity and specificity for detecting injury. As a result, trauma systems are designed to over-triage patients in order not to miss a potentially serious injury. Under- triage of patients should be avoided since a potentially seriously injured patient could be delivered to a facility not prepared to manage their injury. Large amounts of over-triage is not in the best interest of the Trauma System since it will potentially overwhelm the resources of the facilities essential for the management of severely injured patients. Priority 1 Trauma Patients Priority 1 Trauma Patients are patients with blunt or penetrating injury causing physiological abnormalities or significant anatomical injuries. These patients have time sensitive injuries requiring the resources of a Level I or II Trauma Center. These patients may be transported directly to a Level I or II Trauma Center or may require initial stabilization in a Level III or IV Trauma Center and subsequent transfer depending on location of occurrence, and time and distance to the higher level Trauma Center. Alternatively these patients may be cared for in a Level III Trauma Center if appropriate services are readily available. Physiological Compromise Criteria: • Hemodynamic Compromise • Respiratory Compromise • Altered Mentation Anatomical Injury Criteria • Penetrating injury of head, neck, torso, and groin. • Amputation above wrist or ankle. • Paralysis. • Flail chest. • Two or more obvious proximal long bone fractures (upper arm or thigh). • Open or suspected depressed skull fracture. -

HEAD INJURY (GENERAL) Trh1 (1)

HEAD INJURY (GENERAL) TrH1 (1) Head Injury (GENERAL) Last updated: December 19, 2020 DEFINITIONS, CLASSIFICATIONS ............................................................................................................. 2 EPIDEMIOLOGY ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Incidence ............................................................................................................................... 2 Morbidity ............................................................................................................................... 2 Mortality ................................................................................................................................ 2 ETIOLOGY ................................................................................................................................................ 2 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY (PRIMARY VS. SECONDARY INJURY) ..................................................................... 3 PRIMARY BRAIN INJURY ......................................................................................................................... 3 Mechanisms ........................................................................................................................... 3 SECONDARY BRAIN INJURY .................................................................................................................... 3 PATHOPHYSIOLOGY (CEREBRAL BLOOD FLOW, EDEMA) .................................................................... -

Traumatic Brain Injury

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY PATIENT INFORMATION This resource, developed by neurosurgeons, provides patients and their families trustworthy information on neurosurgical conditions and treatments. For more patient resources from the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS), visit www.aans.org/Patients. Traumatic Brain Injury | American Association of Neurological Surgeons A traumatic brain injury (TBI) is defined as a blow to the head or a penetrating head injury that disrupts the normal function of the brain. TBI can result when the head suddenly and violently hits an object or when an object pierces the skull and enters brain tissue. Symptoms of a TBI can be mild, moderate or severe, depending on the extent of damage to the brain. Mild cases may result in a brief change in mental state or consciousness, while severe cases may result in extended periods of unconsciousness, coma or even death. Prevalence About 1.7 million cases of TBI occur in the U.S. every year. Approximately 5.3 million people live with a disability caused by TBI in the U.S. alone. Incidence and Demographics ● Annual direct and indirect TBI costs are estimated at $48-56 billion. ● There are about 235,000 hospitalizations for TBI every year, which is more than 20 times the number of hospitalizations for spinal cord injury. ● Among children ages 14 and younger, TBI accounts for an estimated 2,685 deaths, 37,000 hospitalizations and 435,000 emergency room visits. ● Every year, 80,000-90,000 people experience the onset of long-term or lifelong disabilities associated with TBI. ● Males represent 78.8 percent of all reported TBI accidents and females represent 21.2 percent. -

Trauma Patient Triage Definitions

TRAUMA PATIENT TRIAGE DEFINITIONS Trauma Triage Since patients differ in their initial response to injury, trauma triage is an inexact science. Current patient identification criteria does not provide 100% percent sensitivity and specificity for detecting injury. As a result, trauma systems are designed to over-triage patients in order not to miss a potentially serious injury. Under- triage of patients should be avoided since a potentially seriously injured patient could be delivered to a facility not prepared to manage their injury. Large amounts of over-triage is not in the best interest of the Trauma System since it will potentially overwhelm the resources of the facilities essential for the management of severely injured patients. Priority 1 Trauma Patients These are patients with high energy blunt or penetrating injury causing physiological abnormalities or significant single or multisystem anatomical injuries. These patients have time sensitive injuries requiring the resources of a designated Level I, Level II, or Regional Level III Trauma Center. These patients should be directly transported to a Designated Level I, Level II, or Regional Level III facility for treatment but may be stabilized at a Level III or Level IV facility, if needed, depending on location of occurrence and time and distance to the higher level trauma center. If needed these patients may be cared for in a Level III facility if the appropriate services and resources are available. Physiological Compromise Criteria: Hemodynamic Compromise-Systolic BP <90 mmHg Other signs that should be considered include: o Sustained Tachycardia o Cool diaphoretic Skin Respiratory Compromise-RR<10 or >29 Breaths/Minutes Or <20 in infant <1 year Altered Mentation- of trauma etiology- GCS <14 Anatomical Injury Criteria Penetrating injury of head, neck, chest/abdomen, or extremities proximal to elbow or knee. -

Penetrating Head Injury from Angle Grinder

Published online: 2019-09-25 Case Report Penetrating head injury from angle grinder: A cautionary tale S Senthilkumaran, N Balamurgan1, K Arthanari2, P Thirumalaikolundusubramanian3 Departments of Accident, Emergency and Critical care Medicine, 1Neurosciences, 2Surgery and 3Chennai Medical College and Research Centre, Trichy, India ABSTRACT Penetrating cranial injury is a potentially life-threatening condition. Injuries resulting from the use of angle grinders are numerous and cause high-velocity penetrating cranial injuries. We present a series of two penetrating head injuries associated with improper use of angle grinder, which resulted in shattering of disc into high velocity missiles with reference to management and prevention. One of those hit on the forehead of the operator and the other on the occipital region of the co-worker at a distance of fi ve meters. The pathophysiological consequence of penetrating head injuries depends on the kinetic energy and trajectory of the object. In the nearby healthcare center the impacted broken disc was removed without realising the consequences and the wound was packed. As the conscious level declined in both, they were referred. CT brain revealed fracture in skull and changes in the brain in both. Expeditious removal of the penetrating foreign body and focal debridement of the scalp, skull, dura, and involved parenchyma and Watertight dural closure were carried out. The most important thing is not to remove the impacted foreign body at the site of accident. Craniectomy around the foreign body, debridement and removal of foreign body without zigzag motion are needed. Removal should be done following original direction of projectile injury. The neurological sequelae following the non missile penetrating head injuries are determined by the severity and location of initial injury as well as the rapidity of the exploration and fastidious debridement.