Decision on the Achmea Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Annual Report

2019 Contents. INTRODUCTION About us. 1 This is Ellevio. 2 ELLEVIO 2019 Review of 2019. 4 CEO’S STATEMENT Network vital for climate targets. 6 MARKET CONDITIONS AND DRIVERS Market conditions. 8 The Swedish electricity market – how it works. 11 Drivers. 13 VALUE CREATION From the little things to the big things. 18 Society. 20 Customers. 23 Employees. 26 Environment. 32 Owners. 35 INVESTMENTS AND FINANCING Investments. 36 Financing. 42 ANNUAL REPORT 47 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 75 SUSTAINABILITY DISCLOSURES Management. 80 Results. 83 GRI index. 91 The Annual Report consists of an Administration Report, Financial Statements and notes on pages 45–74. (The auditors’ report appears on pages 73–74.) The sustainability report has been produced in line with Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI) standards ”core” level. The complete sustainability report comprises the description of our sustainability efforts on pages 2–5,8–43 along with Sustainability Disclosures and the GRI index on pages 82–96. The sustainability report also covers Ellevio’s Communication on Progress to the UN Global Compact. The statutory sustainability report in accordance with the Annual Accounts Act can be found on pages 2–5, 18–35 and 82–96. Ellevio AB (publ) Box 242 07 104 51 Stockholm www.ellevio.se All values are expressed in SEK. Figures within parentheses refer to 2018, unless specified otherwise. The data concerning markets and the competitive situation are Ellevio’s own estimates unless a specific source is indicated. These estimates are based on the best and latest available facts from published sources. About us. Sometimes it’s warm, sometimes it’s cold. -

SKI Report 02:18 Nuclear Weapons Research in Sweden Research

SKI’s perspective Background In the year 1998 Sweden, together with the rest of the states in the European Union and Euratom signed the Additional Protocol to the Safeguard Agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency, IAEA. The Additional Protocol gives the Agency extended complimentary access to areas and buildings and rights to take environmental samples within a state. The process of ratification is going on with the intention that the protocol should be implemented simultaneously in all member states. In ratifying the agreement in May 2000, Sweden changed its Act on Nuclear Activities and passed a new law regarding inspections. The present estimate is that the protocol could be implemented in the beginning of 2003 after ratification in all EU member states. Aim When the Additional Protocol is implemented, Sweden is to be “mapped” by the IAEA, scrutinising all nuclear activities, present as well as future plans. In the light of this, SKI has chosen to go one step further, letting Dr Thomas Jonter of the Department of History at Uppsala University investigate Sweden’s past activities in the area of nuclear weapons research in a political perspective. Dr Jonter has previously studied the Swedish National Defence Research Institute’s (FOA) activities in this area up until 1972. This report deals with the civilian research programme and its links to the military plans to produce nuclear weapons. Since Sweden had plans in the nuclear weapons area it is important to show to the IAEA that all such activities have stopped. This is the main objective with this report. Results Dr Jonter has made a survey of available sources in the archives at Studsvik and FOI, where the records of the AB Atomenergi company are stored. -

Certified Environmental Product Declaration EPD of Electricity From

Certified Environmental Product Declaration EPD® of Electricity from Vattenfall Nordic Nuclear Power Plants UNCPC Code 17, Group 171 – Electrical energy The International EPD® system, EPD International AB - In line with ISO 14025 S-P 00923 2019-12-31 Vattenfall AB - Vattenfall AB Nuclear Power Confidentiality class: None (C1) Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 8 1.1. Declared Unit ............................................................................................................ 8 ® 1.2. The Declaration and the EPD system....................................................................... 8 ® 1.3. Vattenfall, LCA and EPD ......................................................................................... 8 2. Producer and product ............................................................................ 9 2.1. Producer .................................................................................................................. 9 2.2. Product System Description .................................................................................... 11 3. Environmental Performance Based on LCA ........................................ 17 3.1. Life Cycle Assessment Method ............................................................................... 17 3.2. Technical Service Life, Reference Flow, Reference Year ......................................... 17 3.3. System Boundaries, Allocation and Data Sources ................................................... -

Environmental Aspects of Load Management

ISRN LUTMDN/TMHP—04/3012—SE Environmental Aspects of Load Management Juozas Abaravicius Report Division of Energy Economics and Planning Department of Heat and Power Engineering Lund University PO Box 118, SE-221 00 Lund, Sweden Environmental Aspects of Load Management by Juozas Abaravicius February 2004 Report This publication is part of the project called Direct and Indirect Load Control in Buildings at the Division of Energy Economics and Planning, Department of Heat and Power Engineering, Lund University, Sweden. Assoc. Prof. Lena Neij from the International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics at Lund University has been supervisor and examiner of this study. Assoc. Prof. Jurek Pyrko from the Division of Energy Economics and Planning, Department of Heat and Power Engineering at Lund University, has been the project leader and supervisor. This work was financed by the ELAN programme- a joint research program on electricity utilisation and behaviour in a deregulated market. The ELAN-programme is financed by the utilities Eskilstuna Energi & Miljo, Fortum, Goteborg Energi AB, the Goteborg Energi research foundation, Jamtkraft AB, Skelleftea Kraft AB, Skanska Energi AB, Sydkraft AB and Vattenfall AB through Elforsk (Swedish Electrical Utilities’ R&D Company), project number 4184-LTH, the Swedish Energy Agency and Formas (The Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning), project number 2001 1846. Report ISRN LUTMDN/TMHP--04/3012--SE © Juozas Abaravicius Division of Energy Economics and Planning Department of Heat and Power Engineering Lund University PO Box 118, SE-221 00 Lund, Sweden www.vok.lth.se/~eep Juozas Abaravicius Environmental Aspects of Load Management Summary Load problems in electricity markets occur both on the supply and demand side and can have technical, economic and even political causes. -

For a Cleaner World

Equity story of FORTUM – For a cleaner world Investor / Analyst material July 2021 Disclaimer This presentation does not constitute an invitation to underwrite, subscribe for, or otherwise acquire or dispose of any Fortum shares. Past performance is no guide to future performance, and persons needing advice should consult an independent financial adviser. Any references to the future represent the management’s current best understanding. However the final outcome may differ from them. 2 Content Fortum in brief 4 – 12 Fortum’s strategy 13 – 22 Energy market transition 23 – 27 Interim report Q1 2021 28 – 45 Appendices 46 European and Nordic power markets 47 – 56 Fortum’s Nordic power generation in detail 57 Fortum’s evolution and strategic route 58 Historical achieved prices 59 Dividend 60 IR contact 61 3 Fortum in brief Fortum in brief Power generation assets Key figures 20201 Sales EUR 49.0 bn Comparable EBITDA EUR 2.4 bn Total assets EUR 57.8 bn Personnel 19,933 Main businesses1 Sales (€) Volume2 Capacity India Power 20.8 bn 142 TWh 50.3 GW Gas 22.4 bn ~370 TWh 7.6 bcm3 Heat 0.8 bn 30 TWh 19.5 GW 1) Until 31 of March 2020 Uniper's contribution to the income statement was recognised in the Share of profit/loss of associates and joint ventures. 2) For Power - Power generation, for Gas - Long-term gas supply contracts and for Heat – Heat production 3) Gas storage capacity, billion cubic meters 4 Fortum in brief Strong position to drive the energy transition in Europe 3rd largest 3rd largest 3rd largest 4th largest power generator CO2-free power generator nuclear generator gas storage operator in Europe and Russia in Europe in Europe in Europe 5 TWh 6 ConsolidatedFortum is third thelargest CO Europe 100 200 300 400 500 600 0 EPH incl. -

For a Cleaner World

Equity story of FORTUM – For a cleaner world Investor / Analyst material September 2020 Disclaimer This presentation does not constitute an invitation to underwrite, subscribe for, or otherwise acquire or dispose of any Fortum shares. Past performance is no guide to future performance, and persons needing advice should consult an independent financial adviser. Any references to the future represent the management’s current best understanding. However the final outcome may differ from them. 2 Content Fortum in brief 4 – 7 Energy market transition 8 – 11 Fortum’s strategic route 12 – 14 Half-Year Financial Report 15 – 35 Appendices 36 European and Nordic power markets 37 – 42 Fortum’s power generation 43 – 44 Historical achieved prices 45 Dividend 46 IR contacts 47 3 Fortum in brief Good position to drive CO2-free power generation in Europe ~60% 3rd largest 2nd largest 66% Increase in Fortum’s of our electricity CO2-free generator nuclear generator CO2-free power in Europe in Europe production in Europe generation was CO2-free in 2019 Fortum in brief Consolidated Fortum is the third largest CO2-free generator in Europe 5 Source: Company information, Fortum analyses, 2018 figures pro forma. EPH incl. LEAG Fortum in brief Fortum to grow and lead European energy transition 2019 combined comparable EBITDA(1,2) Europe & Russia Uniper EUR 1.6 bn EUR 3.3 bn Fortum EUR 1.8 bn Combined power generation (2019)(2) India 18 % 50 % Hydro Nuclear Other ~180 TWh 19 % Coal Gas 1 % Combined power generation assets 12 % Fortum Uniper 1) Comparable EBITDA is based on the Fortum's Comparable EBITDA and Uniper's Adjusted EBITDA as defined in Both Fortum and Uniper Fortum’s and Uniper's financial statements. -

Sports Rights Catalogue 2017/2018

OPERATING EUROVISION AND EURORADIO SPORTS RIGHTS CATALOGUE 2017/2018 1 ABOUT US The EBU is the world’s foremost alliance of The core of our operation is the acquisition Flexible and business orientated are traits public service media organizations, with and distribution of media rights. We work with which perfectly complement the EBU’s well members in 56 countries in Europe and more than 30 federations on a continually established and highly effective distribution beyond. renewable sports rights portfolio consisting of model on a European and Worldwide basis. football, athletics, cycling, skiing, swimming The EBU’s mission is to safeguard the interests and many more. We are proud to collaborate Smart business thinking and commitment to of public service media and to promote their with elite federations such as FIFA*, UEFA*, innovation means the EBU is a key component indispensable contribution to modern society. IAAF, EAA, UCI, FINA, LEN, FIS, IPC, to name at all stages of the broadcast value chain. The a few. EBU is the ideal one-stop-shop partner for the Under the alias, EUROVISION, the EBU broadcast community. produces and distributes top-quality live In 2011, EBU created the Sales Unit to enhance sports and news, as well as entertainment, its competitiveness in an ever-evolving and * EBU Football contracts with FIFA and UEFA are culture and music content. Through extremely challenging industry. The Unit directly handled by the EBU Football Unit. EUROVISION, the EBU provides broadcasters handles the commercial distribution of sports with on-site facilities and services for major rights in EBU’s portfolio in not only European world events in news, sport and culture. -

The Swedish Electricity Market – How It Works

Contents. INTRODUCTION About us. 1 THIS IS ELLEVIO Building the network of the future. 2 CEO STATEMENT Ellevio is modernising the network – for a bright 4 and sustain able future. ELLEVIO 2015 The most important events of the year. 6 STRATEGY Reliable network and committed employees 8 create value. THE SWEDISH The Swedish electricity market – how it works. 10 ELECTRICITY MARKET MARKET DEVELOPMENT Urbanisation, digitalisation and renewable 14 AND OUTLOOK electricity are bringing new demands. REGULATION Our market – a regulated monopoly. 16 INVESTMENTS AND We are investing SEK 9 billion in improvements 18 CUSTOMERS for our customers. FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE Sustainable economy a prerequisite for a sustainable 24 electricity network. SUSTAINABILITY Sustainability – work that strengthens 27 common objectives. EMPLOYEES Committed employees who take responsibility. 32 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Presentation of governance, Board of Directors 34 and Management Team. Ellevio AB SE-115 77 Stockholm, Sweden www.ellevio.se All values are explained in SEK. Figures within parentheses refer to, if nothing else is specified, 2014. The data about markets and competitive situations are Ellevio’s own estimations unless a specific source is indicated. These estimates are based on the best and latest available facts from published sources. About us. All our efforts lead to something you hardly notice: a reliable flow of electricity silently streaming out of your outlet into mobile phones, coffee machines, bedside lamps and other everyday objects making life easier. Or into electric motors that power elevators, pumps and cranes. All in all, our 71,000 kilometers of power lines supply electricity to more than 910,000 house- holds and businesses in Sweden. -

Fortum and Nordic Power Markets

Fortum and Nordic power markets Mikael Lilius President and CEO, Fortum Corporation Enskilda Securities, Finnish Blue Chip Seminar 2005 Helsinki, 22 September 2005 Fortum's strategy Fortum focuses on the Nordic and Baltic rim markets as a platform for profitable growth Become the leading Become the Power and Heat energy supplier company of choice Benchmark business performance 2 Consistent delivery of strategy Restructuring worth 14 billion in 2000-2005 Strengthened position in the Nordic market • increased CO2 -free hydro and nuclear power generation • strengthened position in electricity distribution and retail • foothold in Norway, NW Russia and Poland Disposal of non-core businesses • power and heat businesses outside the Nordic and Baltic Rim focus market • power plant and transmission engineering businesses • gas retail and trading businesses • oil businesses separated 3 Leading market positions in the Nordic area #1 #2 Electricity Power distribution generation Retail sales Heat of electricity 4 Good financial performance 1.44 EPS, EUR 0.91 0.79 0.55 0.57 0.41 1999 200020012002 2003 2004 5 Good returns to shareholders - dividends 0.58* Dividends, EUR 0.42 Dividend policy CAGR: 26% 0.31 Fortum Corporation's 0.26 0.23 dividend policy states 0.18 that the company aims at paying a dividend which corresponds to a payout ratio of 50% to 60% on the average 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 * Cash dividend, Neste Oil shares not included 6 Good returns to shareholders - share price Quotation of Fortum shares and Dow Jones 600 utilities index -

Nuclear Power Plants

IMPLEMENTING COMPUTERIZED INSTRUMENTATION AND CONTROL SYSTEMS AT SWEDISH NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS REPORT 2019:562 NUCLEAR ENERGIFORSK NUCLEAR SAFETY RELATED I&C – ENSRIC Implementing Computerized Instrumentation and Control Systems at Swedish Nuclear Power Plants Assessment of modernization projects BO LIWÅNG AND KARIN FERM ISBN 978-91-7673-562-6 | © ENERGIFORSK February 2019 | Cover photo OKG Energiforsk AB | Phone: 08-677 25 30 | E-mail: [email protected] | www.energiforsk.se IMPLEMENTING COMPUTERIZED INSTRUMENTATION AND CONTROL SYSTEMS AT SWEDISH NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS Foreword Starting in the 1990:ies, a series of modernization projects were initiated to change analogue instrumentation and control systems into computerized technology at the oldest nuclear power plants in Oskarshamn (O1 and O2) and Ringhals (R1 and R2). In this report, this process is documented mainly from the regulator point of view so summarize the experience from these projects. The report is written by Bo Liwång former senior analyst and I&C expert at SSM and Karin Ferm senior management consultant at Evident, in close cooperation with the licensees represented, project team members from the projects covered by this report, Anders Johansson (Vattenfall), Hans Edvinsson (former Vattenfall employee) and Karl-Erik Eriksson (OKG). Stefan Persson, SSM has also contributed to the project. The authors would like to thank all persons involved in the report for taking their time to participate and for their contribution. The activity is included in the Energiforsk Nuclear Safety Related Instrumentation and Control program – ENSRIC. The project is financed by Vattenfall, Sydkraft Nuclear/Uniper, Teollisuuden Voima Oy (TVO), Fortum, Skellefteå Kraft, Karlstads Energi and the Swedish Radiation Safety Authority. -

Annual and Sustainability Report 2020

Annual and Sustainability Report 2020 Climate progress. It's happening. Contents Overview Financial information This is Vattenfall ...........................................................................4 Financial performance ............................................................. 91 CEO’s message ............................................................................6 Consolidated accounts ...........................................................98 Important events ...................................................................... 12 Notes to the consolidated accounts ................................. 104 Parent Company accounts .................................................. 136 Strategic direction Notes to the Parent Company accounts .......................... 139 Auditor’s Report ..................................................................... 151 Business model ......................................................................... 14 Our beliefs about the future ....................................................18 Strategy ......................................................................................20 Sustainability notes Targets and target achievement ........................................... 24 Total value creation ............................................................... 156 Materiality analysis ................................................................ 156 Investments Stakeholders .......................................................................... 157 Environmental -

Q4 Presentation Slides, Analyst and Investor Conference Call (PDF 522

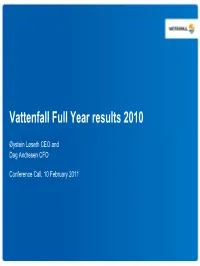

Vattenfall Full Year results 2010 Øystein Løseth CEO and Dag Andresen CFO Conference Call, 10 February 2011 Improved earnings EBITDA, EBIT and Net Sales RoE and Profit after tax SEK bn SEK bn SEK bn % 70 250 25 20 60.7 18 60 20.7 200 20 16 51.8 17.8 50 45.8 46.0 14 40 150 15 13.4 13.2 12 10 28.6 29.9 27.9 29.9 30 100 10 8 6 20 15.4 15.4 5.2 50 5 3.8 4 10 5.7 2.5 4.9 1.7 2 0 0 0 0 2007 2008 2009 2010 Q409 Q410 2007 2008 2009 2010 Q110 Q210 Q310 Q410 1) = Last twelve months EBITDA (LHS) EBIT (LHS) Net Sales (RHS) 1) Profit after tax (LHS) RoE (RHS) • EBITDA and EBIT improved • Improved RoE, but still below target level of 15%. • Modest net sales growth in 2010 due to stronger SEK and the divestment of • RoE excluding IAC was 17.7% 50Hertz Transmission GmbH 2 | Q4 2010 Conference Call | Reduced debt levels and improved credit metrics Debt development Key credit metrics SEK bn 250 FY 2009 Q1/10 Q2/10 Q3/10 FY 2010 200 FFO Interest 4.8 3.71) 4.71) 4.81) 6.2 cover (x) 150 FFO/net debt 23.7 16.81) 24.41) 27.41) 27.8 100 (%) FFO/adj. 17.9 13.31) 20.51) 22.91) 23.1 50 net debt(%) Adj.net debt/ 4.0 3.81) 3.01) 2.91) 2.9 0 EBITDA (x) Gross Debt Net Debt 1) = Last twelve months 31-dec-09 31-mar-10 30-jun-10 30-sep-10 31-dec-10 • Debt reduction mainly due to • Stronger credit metrics.