Britain at the Heart of a Changing World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UK's TRADE DEALS ARE BANANAS CAMEROON PALESTINE

2021 no. 4 June - £6.50 (free to members) UK’s TRADE DEALS ARE BANANAS CAMEROON PALESTINE Belarus Hijack Sakharov EVENTS CONTENTS 7th June LIBG Forum on Afghanistan – see page 3 Afghanistan Forum page 3 21st June Chesham & Amersham by-election. Selling Our Souls for Bananas: Global Britain’s Trade Deals, and Reasons to be Fearful, by 30th June Lib Dems Overseas Zoom Webinar Focus Rebecca Tinsley pages 4-5 on Hong Kong. 12.00-01.30pm – see pages 17-18 Rebuild Samir Mansour’s Bookshop. page 5 1st July Batley & Spen by-election 21st July Paddy Ashdown Forum – What makes a A tribute to Jonathan Fryer, by John good COP? (UN Climate Change Conference). Alderdice pages 6-8 Conversation with LI President Hakima El Haité & Tony Greaves, by David Scott page 8 the UK Liberal Democrats Leader Ed Davey. NLC 6.30-8.00pm – see page 19 Cameroon Forum Report pages 9-10 17th - 20th September – Liberal Democrats Autumn Yabloko host conference and exhibition to Conference. mark centenary of human rights defender Andrei Sakharov. pages 10-11 October 63rd LI Congress will be held online. Details to follow International Abstracts pages 11 & 16 For bookings & other information please contact From the Conference Fringe – Liberal the Treasurer below. Democrat Friends of Palestine report. page 12 NLC= National Liberal Club, Whitehall Place, London SW1A 2HE Belarus Banditry page 13 Underground: Embankment Reviews pages 14-17 Focus on Hong Kong Webinar pages 18-19 Liberal International (British Group) Treasurer: Wendy Kyrle-Pope, 1 Brook Gardens, What makes a good COP (Paddy Ashdown Barnes, Forum) page 20 London SW13 0LY email [email protected] Photographs: Stewart Rayment, Jonathan Fryer, Rebecca Tinsley, Yabloko, Samir Mansour InterLib is published by the Liberal International (British Group). -

Politics and International Studies Newsletter

Politics & International Studies Newsletter, no. 5 February 2012 Politics and International Studies Newsletter Middle East? The conference, organised for 25 February, in the 50 Years of Politics at SOAS Introductions Khalili Lecture Theatre, is set to examine the revolutionary uprisings that have taken place across the Middle East in the past year. These uprisings have thus far produced dynamic societal developments that include new governments, transformed socio- political discussions, military intervention, and constitutional changes. This one-day conference seeks to address these issue areas, as well as others, in the hopes of better A Note of introduction from Alex understanding the hopeful Craven: opportunities and significant challenges that lie ahead for the “Hi everyone - my name is Alex Mark Friday and Saturday 24 & region and its peoples. Craven and I have just joined 25 February in your diaries! SOAS as the academic support The Department of Politics and This student-organized conference officer for the Politics Department. International Studies will celebrate will feature academics, activists, and I studied History at Oxford its fiftieth birthday on 24 February, journalists. Panels will include: University, and after graduating starting at 18.30 in the Brunei spent three years working at Gallery Lecture Theatre. The Geopolitical Challenges to Wadham College in Oxford, before event will include a panel followed Political Change moving to London last September. Away from work I am a keen film by a party in the Brunei Suite from Justice, Intervention, and the buff (I volunteer at a cinema 8pm onwards. Students, colleagues, Rule of Law in Transition and alumni are especially welcome. -

Liberator September 2020

A shot of this would protect you 0 0 Illiberalism and identity politics - David Grace Radical 0 Does the Compass point to inter-party dealings - Simon Hebditch A pandemic of mental health problems - Claire Tyler liberalism Issue 405 - February 2021 £ 4 Issue 405 February 2021 Liberator is now free to read CONTENTS as a PDF on our website: www. liberatormagazine.org.uk and Commentary.............................................................................................3 please see inside for details of Radical Bulletin .........................................................................................4..7 how to sign up for notifications “YOU’RE ALL INDIVIDUALS” of when issues come out. “I’M NOT” ................................................................................................8..9 It’s Life of Brian’s most famous exchange, but identity politics is denying individuality See the website for the ‘sign up and will end up in aggressive nationalism, says David Grace to Liberator’s email newsletter’ NOT ALL THAT STUFF, AGAIN ...........................................................10..11 link. There is also a free archive Labour can’t win a majority and the Lib Dems and Greens can’t make much progress, of back issues to 2001. it’s time again for cross-party co-operation says Simon Hebditch MARCHING AWAY FROM THE SOUND OF GUNFIRE ..................12..13 The drift of the Liberal Democrats risks becoming terminal unless radical action is taken, to fight for people’s freedoms, writes Gareth Epps THE LIBERATOR THE PANDEMIC’S -

And Lib Dems?

2018 no.8 £6.50 (free to members) Iran/USA Guatemala Liberal Democrat Conference Reports March for a People's Vote, 20th October London EVENTS CONTENTS 8th-11th November ALDE Congress, Madrid. Liberal Democrats Brighton Conference pages 3-19 LIBG Fringe: Iran and JCPOA; Jaw Jaw or War 23rd-25th November IFLRY 44th General Assembly, War? pages 3-7 Barcelona. The US justification for withdrawing from 28th-30th November LI Congress, Dakar, Senegal. the JCPOA (nuclear agreement), by Paul E M Reynolds pages 3-5 December LIHRC, Copenhagen Re-imposition of Nuclear-Related U.S. Sanctions Against Iran, by Bahram 7th February 2019 Scottish Group meeting with Ghiassee. pages 5-7 Baroness Alison Suttie. Details to be announced. Contact [email protected] Liberal Democrat Friends of Israel Fringe: Donald Trump and the Middle East: potential 22nd-23rd February 2019 Scottish Liberal Democrat peace maker or dangerous loose cannon? Conference, Hamilton by Monroe Palmer. page 8 16th-17th March 2019 Liberal Democrat Conference, Liberal Democrat Friends of Palestine Fringe York “What Hope for Palestine in the Era of Trump?” by Jonathan Fryer pages 9-10 24th June 2019 NLC Diplomatic Reception Liberal Democrat Friends of Pakistan. page 10 14th-17th September 2019 Liberal Democrat’s Conference. Bournemouth Liberal Democrat Friends of Palestine Fringe: LDFP fringe meeting notes an IHRA elephant For bookings & other information please contact the in the room, by Jonathan Coulter pages 11-13 Treasurer below. Lib Dems For Seekers of Sanctuary pages 13-18 NLC= National Liberal Club, Whitehall Place, Policies adopted at the Federal Conference London SW1A 2HE relating to seekers of sanctuary page 13-14 Underground: Embankment LD4SoS Fringe: ‘How should the UK change its refugee family reunification policies?’ by Ruvi Ziegler. -

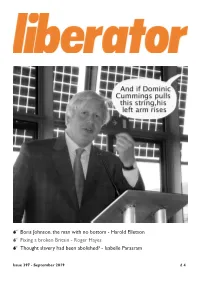

Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a Broken Britain

0 Boris Johnson, the man with no bottom - Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a broken Britain - Roger Hayes 0 Thought slavery had been abolished? - Isabelle Parasram Issue 397 - September 2019 £ 4 Issue 397 September 2019 SUBSCRIBE! CONTENTS Liberator magazine is published six/seven times per year. Subscribe for only £25 (£30 overseas) per year. Commentary .................................................................................3 You can subscribe or renew online using PayPal at Radical Bulletin .............................................................................4..5 our website: www.liberator.org.uk THE MAN WITH NO BOTTOM ................................................6..7 Or send a cheque (UK banks only), payable to Boris Johnson might see himself as a ’great man’, but is an empty vessel “Liberator Publications”, together with your name without values says former Tory MP Harold Elletson and full postal address, to: IT’S TIME FOR US TO FIX A BROKEN BRITAIN ....................8..9 After three wasted years and the possible horror of Brexit it’s time Liberator Publications for the Liberal Democrat to take the lead in creating a reformed Britain, Flat 1, 24 Alexandra Grove says Roger Hayes London N4 2LF England ANOTHER ALLIANCE? .............................................................10..11 Should there be a Remain Alliance involving Liberal Democrats at any imminent general election? Liberator canvassed some views, THE LIBERATOR this is what we got COLLECTIVE Jonathan Calder, Richard Clein, Howard Cohen, IS IT OUR FAULT? .....................................................................12..13 -

Candidates' Election Statements

CANDIDATES’ ELECTION STATEMENTS Election to the Management Committee 2020 Please read carefully before casting your vote. Candidates are listed in random order. M1934_1_P2 PHILIP WOMACK JANE O’REILLY I am standing for a second term, as I I write fiction for adults and have been believe that this is a critical time for published in various genres, digitally and authors, and for all those in the creative traditionally, with and without an agent. industries. It’s vital that we have a I have been a member of the Society of voice, and for that voice to continue Authors since 2017 and took over the to be heard in the right places. Our running of the Hertfordshire members membership is rising, and I hope to see group from Sam Collett in 2018. I’m also it rise still further. a member of the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA) and run one of their I have served on the Management Orbit Short Story critique groups, and Committee for three years, during which a member of the Chartered Institute of time I have chaired the Campaigns sub- Editing and Proofreading (CIEP). committee and seen its success in lobbying government about VAT on ebooks. I have learned a huge amount about My experience as a group leader has shown the importance the structures and governance of the Society of Authors, and of being able to network with other writers and draw from am passionate about continuing to play a role in furthering a wide pool of knowledge. Working collectively opens doors the rights of authors. -

Autumn Conference

Autumn Conference Bournemouth 19th – 23rd September 2009 Conference Directory A fresh start for Britain Choosing a different, better future All the big health debates under one roof THE HEALTH HOTEL Supported by: )%/7,$21)<*5)),)%/7,7)67-1+%(9-')%1(0%66%+) %785(%; 72")(1)6(%;)37)0&)5%-1175%1') Monday 21 September 8;12:3%;/%7)5 5)+8/,2//%1( < 85/);220 "-11-1+7,)&%77/)*25,)%576%1(&5%-16250%1%0& < 5%1.620)220 %7-)176%*)7; %1)/)'7-2135-25-7; %1(5%-(/); < 921220 "-//3%7-)176&)6%*)-17,)-&)5%/)02'5%76=,%1(6 %1(5%-(/); < 85/);220 Specialised Healthcare Alliance 5)(-7581',72)%/7,581',%521)66%5.)5 < %;9-):8-7) 927)*25,)%/7, 250%1%0& < 5)+21:)//220 !""# 250%1%0& %1()&%7) Supported by: < 85&)'.8-7)-+,'/-**)%55-277 )%/7,27)/)')37-21:-7,%1%((5)66&;250%1%0& Supported by: < 25',)67)58-7)-+,'/-**)%55-277(invitation only) Tuesday 22 September 1)-17,5)) %'./-1+'%1')5-6%1)/)'7-21-668) %1(5%-(/); < 5)+21:)//220 )5621%/-6-1+'%5) 7,)',2-')6:)*%')250%1%0& < 85/);220 ,))%/7,'%5)-1(8'%7-21,%//)1+) 5)+8/,2//%1( < 5%1.620)220 )0)17-%()'%() %'85)&; 5)+8/,2//%1( < %;9-):8-7) 520",-7),%//727,)72:1,%//<no longer a national health service? 2,18+, < 5)+21:)//220 %6,*25,)%/7, 3%;-1+7,)35-')*2548%/-7; %1(5%-(/); < 5%1.620)220 Health Hotel non-fringe members: 25025)-1*250%7-216))%77%',)(352+5%00)259-6-7 www.healthhotel.org.uk *;285)48-5)7,-6%(9)57-6)0)17-15%-//)/%5+)35-1725%8(-23/)%6)'217%'7 Introduction Contents Welcome to the Conference Directory for Features: the Liberal Democrat autumn 2009 federal Welcome to Bournemouth 3 conference. -

Meeting/Talks List

The Probus Club of Sandown - Meeting/Talks List Page 1 of 10 Printed 11Nov19 Event Date Topic Speaker 01Dec20 Catching Smugglers Part 1 Malcolm Nelson 03Nov20 Conspiracy Theories of the World Andy Thomas 06Oct20 The American Civil War David Skillen 01Sep20 Surviving 30 years at the BBC Julian Worricker 04Aug20 Inn and Out at the Top Neil Hanson 14Jul20 A Trip on the Royal Train Graeme Payne 02Jun20 Norfolk Island, Prisoners and Mutineers Barry Stephens 07Apr20 Antibiotic Research Claire Nethersole 03Mar20 Behind the Scenes of ITV's Golden Years Wilf Lower 04Feb20 The Life of the Antique Dealer Michael Laikin 07Jan20 Big Ben Tim Redmond 03Dec19 Samuel Cody [not to be confused with William Cody] Bill McNaught 05Nov19 History of the Tea trade Dananjaya Silva 08Oct19 Artist Village: The Watts Gallery Jane Turner 03Sep19 FROM ABSURDITIES TO ZEALOTRY Susan Purcell 06Aug19 Stalking Hamish Brown 09Jul19 The Roman Villa Dr Hannah Platts 04Jun19 Kazakhstan Hugh Thomas 07May19 Annual General Meeting AGM 02Apr19 Petticoat Pilot - Learning to Fly at 52 Ann Chance OBE 05Mar19 Introduction to China David Steeds 05Feb19 MAD CAP IDEAS - QUIRKY INVENTIONS Doug Eaton 08Jan19 The History of the 5 Ark Royals David Snelson 04Dec18 Nuclear Fusion: Power for the Future Robin Allen 06Nov18 Down Memory Lane with Johnny Cooper Graeme Cooper 09Oct18 Flying from the pilots point of view Lorimer Burn 04Sep18 Middle East: religion, politics and sectarianism Nabil Mustapha 07Aug18 The Amazing History of Lighthouses Mark Lewis 10Jul18 The Art of Story Telling Adrienne -

25 February 2011 Page 1 of 16

Radio 4 Listings for 19 – 25 February 2011 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 19 FEBRUARY 2011 There are too many horses for the number of good quality changing its membership rules to allow Liberal Democrats to homes available for them in the UK, according to the country's join. He and Julian Astle of the Liberal Democrat think tank SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b00yjtgz) biggest horse charity Redwings. CentreForum talk about how British politics is adapting to The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. coalition politics. Followed by Weather. Charlotte Smith speaks with horse riders in North The editor was Marie Jessel. Warwickshire about the financial strain of keeping the animal. Anna Hill visits World Horse Welfare in Norfolk who have SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b00yl3yh) taken in 230 horses in the last year. SAT 11:30 From Our Own Correspondent (b00ym6cm) The 33 The roots of the rage that has rocked the tiny kingdom of Horse owners, carers and riders in Britain spend more than £7 Bahrain. Episode 5 billion per year in gross output terms, Charlotte visits the London Equestrian Centre in Barnet to see if it is still in the How an "age of recklessness" ruined Ireland. The 33 by Jonathan Franklin current economic climate. The ancient North-South division that still splits hearts and In 2010, the world turned towards Chile when the collapse of a Also, we hear from Stephen Potter who runs an abattoir in minds in Italy. copper mine left 33 men to survive underground for almost 3 Taunton about the possibility of selling horses for meat and months, the longest time in history. -

Alan Johnston Petition

ALAN JOHNSTON PETITION BBC News website users around the world have written in their thousands to demand the release of BBC Gaza correspondent Alan Johnston. An online petition was started on Monday, 2 April. It said: “We, the undersigned, demand the immediate release of BBC Gaza correspondent Alan Johnston. We ask again that everyone with influence on this situation increase their efforts, to ensure that Alan is freed quickly and unharmed.” More than 135,000 have signed. The latest names to be added are published below. A A Johnson Paderborn, Germany A Rubin California, USA a ahmed London UK A Tague Streatham, London A Beech Birmingham, UK A Tinsley Wakefield, United A Beirne Derry, Ireland Kingdom A Biggs herts england A Walsh Canada A Bishop UK A Wilson Cupar, Fife, Scotland A Bowes West Mids. UK A Witts Bridgend, Wales a doneathy paignton devon uk A Woltman Exmouth England A J Williams Birmingham, UK A. Banks Staffordshire, England A James Taichung Taiwan A. Chidanandan Terre Haute, U.S.A. A Jamieson Edinburgh, Scotland A. Lacey-Kormos Mississauga, A Khokher Aylesbury England Canada A L Marlin Sevenoaks, UK A. McGregor La Jolla, USA A Lee London, UK A. Nimer Amr Göttingen, Germany A Luke England A. Parke Dumfries, Scotland A Mannion England A. Wong London, UK A.C. de Roij-van Gils Tilburg The Abdulelah Othman Riyadh, Saudi Netherlands Arabia A.J.Cole London, UK Abdullah Mohamad Khoury A.L.Cody USA Lebanon A.Siva South Croydon, England Abdurrahman al-Jarsha Riyadh, A.Timte Berlin , Germany Saudi Arabia Aaron Clark Wolverhampton, UK Abe Hamu Kochi, Japan Aaron Cohen Saratoga, USA ABEBE NEGASSA LAMU Aaron Fox Brooklyn, NY, USA Minneapolis. -

The Minor Transnationalism of Christopher Isherwood

CENTRAL EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY A SINGULAR NOMAD: THE MINOR TRANSNATIONALISM OF CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD by CALVIN W. KEOGH Doctoral Dissertation Submitted to Central European University Gender Studies Department In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Comparative Gender Studies CEU eTD Collection Supervisor: Jasmina Lukić Budapest, Hungary August, 2018 CEU eTD Collection Declaration I hereby declare that this dissertation contains no materials previously accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions, and contains no materials previously written and/or published by any other persons, except where appropriate acknowledgement is made in the form of bibliographic reference. Calvin W. Keogh CEU eTD Collection CEU eTD Collection Abstract This project brings a transnational perspective to the work of Christopher Isherwood (1904-86), a writer who began his career in the UK in the 1920s, established his reputation in mainland Europe in the 1930s, and published most of his writing in the US from the 1940s-80s. Transnationalism in literary studies is presented as a critical methodology of selection and analysis, which calls attention to the work of migrant writers and involves a sophisticated approach to related issues of identity, selfhood, and subject positioning. A selection of novels and novellas from the three main periods of Isherwood’s career is made according to his concept of Wanderjahren, or years of wandering, which refers to a time from before he left London in the 1920s to when he felt settled in the US in the 1960s. For the purposes of analysis, ‘minor transnationalism’ is presented as a theoretical framework on the basis of the philosophy of nomadism and the related concept of minor literature as devised by Gilles Deleuze (1925-95) and Félix Guattari (1930-92). -

Seminar Transcript House of Commons 10Th March 2016

Seminar Transcript House of Commons 10th March 2016 مركز العودة الفلسطيني PALESTINIAN RETURN CENTRE Organisation in consultative status with the Economic and Social Council since 2015 1 The Palestinian Return Centre is an independent consultancy focusing on the historical, political and legal aspects of the Palestinian Refugees. The organization offers expert advice to various actors and agencies on the question of Palestinian Refugees within the context of the Nakba - the catastrophe following the forced displacement of Palestinians in 1948 - and serves as an information repository on other related aspects of the Palestine question and the Arab-Israeli conflict. It specializes in the research, analysis, and monitor of issues pertaining to the dispersed Palestinians and their internationally recognized legal right to return. Title: The Palestinian Nakba: 68 Years of Diaspora Seminar delivered: May 10th, 2016; Houses of Parliament, London ISBN: 978 1 901924 66 4 Copyright © Palestinian Return Centre 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission of the copyright owner. Disclaimer: The views expressed by the speakers in the transcribed text below do not reflect the views of the Palestinian Return centre or its event’s partners. 2 Table of Contents Preface .....................................................................................................................................1 Speakers ..................................................................................................................................1