Constructing a Modern Architectural Identity in Rural Queensland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MSAA/LSAA Conf Proceedings

LSAA 2000 AUCKLAND STRUCTURAL EXPRESSION INARCHITECTURE Harry Street Design Director at Creative Spaces Ltd Abstract A personal view of how structure can be employed to create exciting and memorable buildings. Commencing with the English 'Hi Tech' architects, the influence of Philip Cox and work at Creative Spaces the address will illustrate with the aid of slides how structural concepts, their expression and how they are detailed can generate a vibrant interesting architecture. Introduction Expressing the structure in buildings, making it evident how they stand up, has been a legitimate, although perhaps not always intentional, form of architectural expression since time immemorial. There can be no doubt about how the roof of the Parthenon on the acropolis was held up. This was probably not the designer's main motivation when considering the buildings aesthetics, nor indeed the primary motivation of many others over the centuries. Nevertheless the structure is there for us to appreciate in this and in many other examples. The English Experience My own understanding of this was slow in dawning, but following my formal training and during my O.E. Iwas attracted to the exciting architecture of the English architects of the 70's where structural expression was a key ingredient of the so-called "Hi Tech" aesthetic. The most memorable buildings of this period included: The Centre Pompidou where everything is expressed, nothing hidden, all in its right place and very ordered through the use of strong colour The Willis Faber Dumas building in Ipswich is a far less exuberant example of the style. Nevertheless the relatively conventional concrete structure of round columns and waffle slab is plainly evident. -

Allora Pharmacy I Have Witnessed Quite a Few Near Misses with People Trying to Contributes to High Blood Pressure and High Cholesterol

Issue No. 3525 The AlloraPublished by OurNews Pty. Ltd.,Advertiser at the Office, 53 Herbert Street, Allora, Q. 4362 “Since 1935” Issued Weekly as an Advertising Medium to the people of Allora and surrounding Districts. Your FREE Local Ph 07 4666 3089 - E-Mail [email protected] - Web www.alloraadvertiser.com Wednesday, 9th January, 2019 Op Shop Open Under New Banner Bob Burge, Trevor Shields and Nev Laney from Allora Men’s Shed convert the Blue Care Cottage to enable clothing and other goods to be suitably displayed. The Allora Op Shop, members of the Allora previously operated on Men’s Shed, the Blue Care behalf of Blue Care re- cottage has been renovated opened on Tuesday under to enable volunteers to organise the display of the auspices of the local Scope Club members Jill (kneeling) Heather, Lynn and Helen set up Scope Club. clothing and other items. the banner in preparation for the first day of trading under the new With the support of name. good honest service 572 Condamine River Road, PRATTEN 432 ha A Rare Gem in a Magnificent Setting Location, charm and production versatility very seldom are delivered in one parcel. Previously • John Dalton architecturally designed five bedroom homestead the home of a successful Santa Gertrudis stud, this property has only changed hands twice • Air-conditioned and combustion heating with two formal lounges since settlement. • Fully ensuited guest-room, fully screened verandahs, magnificent views over the Mount Manning offers the capability of breeding and backgrounding with the added bonus Condamine River of fertile irrigated river flats with undulating grazing country. -

Hansard 5 April 2001

5 Apr 2001 Legislative Assembly 351 THURSDAY, 5 APRIL 2001 Mr SPEAKER (Hon. R. K. Hollis, Redcliffe) read prayers and took the chair at 9.30 a.m. PETITIONS The Clerk announced the receipt of the following petitions— Western Ipswich Bypass Mr Livingstone from 197 petitioners, requesting the House to reject all three options of the proposed Western Ipswich Bypass. State Government Land, Bracken Ridge Mr Nuttall from 403 petitioners, requesting the House to consider the request that the land owned by the State Government at 210 Telegraph Road, Bracken Ridge be kept and managed as a bushland reserve. Spinal Injuries Unit, Townsville General Hospital Mr Rodgers from 1,336 petitioners, requesting the House to provide a 24-26 bed Acute Care Spinal Injuries Unit at the new Townsville General Hospital in Douglas currently under construction. Left-Hand Drive Vehicles Mrs D. Scott from 233 petitioners, requesting the House to lower the age limit required to register a left-hand drive vehicle. Mater Children's Hospital Miss Simpson from 50 petitioners, requesting the House to (a) urge that Queensland Health reward efficient performance, rather than limit it, for the high growth population in the southern corridor, (b) argue that Queenslanders have the right to decide where their child is treated without being turned away, (c) decide that the Mater Children’s Hospital not be sent into deficit for meeting the needs of children who present at the door and (d) review the current funding system immediately to remedy this. PAPERS MINISTERIAL PAPER The following ministerial paper was tabled— Hon. R. -

AN AUSTRALIAN ARCHITECTURAL SAGA This Draft Summary Clarifies A

AN AUSTRALIAN ARCHITECTURAL SAGA This draft summary clarifies a 60 year political saga in Australian architectural politics, beginning with the arrival in Sydney of Harry Seidler in 1948 and continuing via his widow Penelope and her supporters after Seidler’s death in 2006. The angle for this version of the saga focuses on architectural politics around author Davina Jackson’s corruptly failed PhD thesis on Seidler’s main early rival in Sydney, Douglas Snelling. An earlier version of this text has been submitted to the Victorian Ombudsman, the NSW Board of Architects, and other relevant government agencies. It also has been circulated to key leaders of Australia’s architectural culture (including Michael Bryce at the Governor General’s Office) – with no questioning of the facts or interpretations. Three lawyers have seen this text and while one advises ‘this saga is so shocking it can never be officially admitted’, the facts have been so comprehensively recorded, circulated and witnessed, there is no realistic potential for the Seidlers, or other named protagonists, to deny their roles either. ......... In the age of the leak and the blog, of evidence extraction and link discovery, truths will either out or be outed, later if not sooner. This is something I would bring to the attention of every diplomat, politician and corporate leader: The future, eventually, will find you out. The future, wielding unimaginable tools of transparency, will have its way with you. In the end, you will be seen to have done that which you did. —William Gibson. 2003. ‘The Road to Oceania’ in The New York Times, June. -

Ajejii|U&Jc but Never Heard; Efficiently You'll Graduate in Dull on Predigested Tidbits of Solemnity

5c-A* ^f^ He wants a brave new University, Forget your songs, runs the Wh(jr e undergrads will all decree be kept In cages; — Students should be seen And there they will be fed >ajejii|u&jc but never heard; efficiently You'll graduate in dull On predigested tidbits of solemnity. the wisdom of the THE U.Q.U. NEWSPAPER Now "Gaudeamus" is de- ages. dared a dirty word. Regtstered at tl>e C.P.O., Brisbans. lor Friday, April 28, 1961 transmission by post as a periodical. Volume 31, No. 4 Atithorised by J. Fogarty and J. B. Dalton, c^^nlversify Union Offices, St. Lucia. Printed by Watson, Ferguson and Co., Stanley Street, Soulh Brisbane iiiiiMi^iMiriiiiiG: Mr. Bishopp said that pranks he considered in "I'll really fix things for us," he said. bad taste were squirting policemen with a solu "I'll issue the force with new orders. No tion of chewing guna and arsenic, or sinking arresting Varsity men. If any cops are sprayed American ships. with bubble gum and arsenic they must stand still He said that the until their flat feet develop tinea. first mentioned prank "No interfering with any pranks at all by was "shocking" as the Varsity men. Anything is allowed at the proces poor policemen's flat sion. Smut, nudes, politics, smut — say maybe feet were glued to the we could do a float on the joke about the old priest and the young priest. "Just so we'll be safe I'll get all the bodgies ground with the gum/ rounded up for the week. -

White Steel: the Sports Building Works of Philip Cox, From

White Steel The sports building works of Philip Cox, from 1977 and their global influence Stuart Harrison Page 1 of 6 While COX Architects & Planners (COX) has grown into a multi-city and internally is overt –Philip Cox attributes this to large rural buildings such as the international practice of many collaborators, this essay will look at the COX Cooling Towers in Kuri Kuri, New South Wales.ii The expression of structure ‘manner’ and language developed by founder Philip Cox through the sports and for Bruce stadium ‘comes outside’ in contrast to the internal expression at events projects of the firm in the latter part of the twentieth century. This is a Tocal. The Kambah Health Centre, 1973, also features an internal expression of story that starts in Canberra with the National Athletics Stadium and becomes a structure, with a large central timber truss creating an open-span working successful and influential approach for major sports buildings, perhaps best environment. demonstrated by the Sydney Football Stadium of 1988. This path also reveals a strong interest in an Australian ‘functional tradition’ of construction, structural The Bruce stadium was considerably extended in the 1990s when it was innovation such as the emerging ‘high tech’ work in England, the tensile converted from an athletics venue to a more general-purpose stadium, home experimental buildings of Frei Otto, and a tradition of structural expression in now to Canberra’s rugby teams and a rectangular pitch. The original black and Australian architecture. Of particular interest is the practice's 'white stadia white photographs of this exceptional project show the stadium’s careful expressionism', which, after 1988, is adopted by other architects and becomes integration into the bushy landscape of the Canberra suburb of Bruce. -

MICHAEL RAYNER AM Barch(Hons1) UNSW, LFRAIA, FTSE, RIBA

MICHAEL RAYNER AM BArch(Hons1) UNSW, LFRAIA, FTSE, RIBA DIRECTOR CONTACT BACKGROUND PROFESSIONAL M. +61 417 711 418 Michael Rayner is a Director of Blight Michael is a Past President of the E. [email protected] Rayner Architecture formed in 2016. He Australian Institute of Architects was previously Principal Director of Cox Queensland Chapter (2000-02). He Rayner Architects which he established has served on several Queensland in Brisbane in 1990. In both capacities, Government Boards and Councils, EDUCATION Michael has contributed widely to the including the Premier’s Smart State Bachelor of Architecture (Honours 1), urban design quality of Queensland, Council (2006-12), Queensland Design University of New South Wales, 1980 and he has been integral in the Council (2009-12) and Creative Industries creation of major international public Leadership Group (2004-12). He was buildings such as the National Maritime a representative of the Health sector Museum of China in Tianjin and the at the Australian Government’s Ideas MEMBERSHIPS + AFFILIATIONS Helix Pedestrian Bridge in Singapore. Summit in Canberra in 2008, and a Member of the Order of Australia (AM) Councillor of the Australian Business Michael is a Life Fellow of the Australian Fellow, Australian Academy of Arts Foundation (1997-2011). He has Institute of Architects and a Fellow of Technological Sciences + Engineering been a member of the Brisbane Lord the Academy of Technological Sciences Life Fellow, Australian Institute of Architects Mayor’s Urban Futures Board (2008-12) and Engineering. In 2011, he was Associate, Royal Institute of British Architects and Independent Design Advisory Panel appointed a Member of the Order of (2006-12). -

Student Biennale Prize Winners 1985 – 2010

Student Biennale Prize Winners 1985 – 2010 Year Prize Winners/Commendations Finalists/Exhibited entries Jury Entries 1985 No outright winner, 6 RAIA Paul Evans , RMIT Danny Nutter , Immediate 42 Student Biennale Awards Richard Francis-Jones , University of Past President RAIA Sydney Daniel Callaghan , Lecturer in Janelle Plummer , University of Sydney Architecture, Queensland Reg Lark , University of New South Wales Institute of Technology Peter Greiner , Tasmania CAE Gordon Holden , Biennale Jillo Shelton , Un iversity of Western Australia Coordinator RAIA ArchitectureRAIA Students Biennale Design and Awards Exhibition 1987 RAIA Student Biennale Sue Royle , RMIT Alice Hampson , University of Gordon Holden , Panel 125 Award & Project: A museum to exhibit the treasures Queensland Chairman; Director BHP Steel Building of Tutankhamun Annabel Lahz , University of Architecture Students Products Award for a Queensland Biennale Awards, Brisbane Project of Outstanding Stephen Penney , NSW Institute of Philip Cox , Chairman, RAIA Merit Technology National Education Yat Weng Chan , University of New Committee, Sydney RAIA Student Biennale Graeme Dix , Canberra College of Advanced South Wales Graham Hulme , Immediate Award Education George Yiontis , RMIT Past President RAIA Sue McRobbie , University of Queensland Ian McDougall , Architect Alan Johnson , Public Works Department, Melbourne NSW Tim Penny , Senior Student, Caroline Diesner , Department of Housing Tasmania State Institute of and Construction, ACT, University of Sydney Technology RAIA -

The Pleasures of Architecture'

Research Collection Conference Paper Architects on the Verge: Distance in Proximity at 'The Pleasures of Architecture' Author(s): Gosseye, Janina; Watson, Donald Publication Date: 2020 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000390856 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library Architects on the Verge: Distance in Proximity at “The Pleasures of Architecture” Janina Gosseye ETH Zurich Donald Watson University of Queensland Between May 23 and 26, 1980, the New South Wales chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects held a conference in Sydney, entitled “The Pleasures of Architecture.” International guests invited to speak at this conference were Michael Graves, George Baird and Rem Koolhaas. To feed the discussion, the conference organisers invited twenty prominent Australian architects to submit a design to fictionally complete Engehurst, an 1830s villa in Paddington (Sydney) originally designed by architect John Verge, which was never completed and of which only a fragment still existed. All schemes were presented in an exhibition that took place in parallel with the conference. The proposed projects were published in full in the April/May 1980 issue of Architecture Australia and were remarkably diverse in their conceptual approach to the completion of Verge’s villa. Recent scholarship pinpoints “The Pleasures of Architecture” conference as a -

Continuing the Lauries Journey

www.slcoldboys.com.au On College Hill Continuing the Lauries Journey The Official Publication of the St Laurence’s College Old Boys’ Association June/July 2019 Mailing Address: SLOBA Registrar SLOBA Registrar Phone: 07 3010 1178 St Laurence’s College Email: [email protected] 82 Stephens Road South Brisbane QLD 4101 A Publication of the St Laurence’s College Old Boys’ Association—June/ July 2019 Page 1 On College Hill Continuing the Laurie’s Journey In this Edition From the Association 3 From the Foundation 4 A Message from Chris—College Principal 5 SLOBACare 6 Q3 /4 2019 Key Dates 7 Save the Date—Reunion Weekend 8 Mikel Mellick (‘89) - The Psychology of Sport 9 Our Latest Honorary Life Members 14 The Runcorn Project Update 17 On the Board at #1—John Dalton (‘52) 17 Back to Runcorn Day Old Boys Challenge 19 Back to Runcorn Function 21 Know your History—Take the Crossword Challenge 23 “Woody Cup” Report 24 College Cultural and Sporting Update 28 College Anzac and Race Day 31 On the Grapevine…. 32 We Pray 33 Plus, Our Service Record, 2021 Year 5 intake deadline, College Corporate Lunch and the 2019 Musical, “The Addams Family” and From the Past…... 2019 Committee: President: Peter Wendt (‘88); Vice-President—Antoni Raiteri (‘84); Secretary—Michael Campbell (‘72); Treasurer—Chris Webster (‘69)/ Michael Campbell (‘72); Junior Vice-President—Jock Scahill (‘10); Registrar—Helen Turner; Committee—Di Taylor (Life Member); Denis Brown (’59), Chris Skelton (‘78), John Dinnen (‘78), Anthony Samios (‘80), Scott Stanford (‘89), Cameron Wigan (‘95), Steve Leszczynski (‘96), John O’Brien (‘98) A Publication of the St Laurence’s College Old Boys’ Association—June/ July 2019 Page 2 On College Hill Continuing the Laurie’s Journey From the Association Peter Wendt (’88) - President Welcome to our mid year newsletter - I hope you find it to be an enjoyable and informative read. -

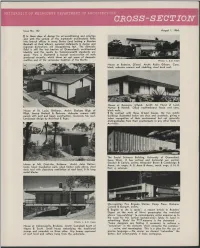

Cross-Section, Aug 1964 (No

NIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE CROSS-S if In these days of design for air-conditioning and prestige and with the spread of the mammoth architectural firms into branch offices in many States (and lacking a Gordon Bunshaft at their elbow), personal statements in design and regional distinctions are disappearing fast. The domestic field is still the last bastion of Queensland's architectural identity and the results by Commonwealth standards are good. Here is illustrated a typical cross-section of work produced recently, which shows an apt sense of domestic realities and of the vernacular tradition of the North: Photo: L. & D. Keen House at Buderim, Q'land. Archt: Robin Gibson. Conc. block, asbestos cement wall cladding, steel deck roof. House at Kenmore, Q'land. Archt: M. Hurst of Lund, Hutton & Newell. Oiled weatherboard fascia and conc. House at St. Lucia, Brisbane. Archt: Graham Bligh of block walls. Bligh, Jessup Bretnall & Partners. Asbestos cement infill By contrast with these Q'land houses, the two public panels with post and beam construction. Concrete tile roof. buildings illustrated below are dour and uncertain, giving a Landscape design by Architect B. Ryan. token recognition of their environment but not generally distinguishable from their counterparts in any other State in Aus+ralia: The Social Sciences Building, University of Queensland, faces West. It has vertical and horizontal sun control. Goodsir & Carlyle, archts; Alexander Brown & Cambridge & House at Mt. Coot-tha, Brisbane. Archt. John Dalton. Assoc., str. engrs; A. E. Axon & Assoc., mech. engr; J. H. B. Conc. block foundation walls, oiled timber walls above, steel Kerr, q. -

Download Sapphire by the Gardens E-Brochure

EXCLUSIVE RESIDENCES 308 EXHIBITION ST MELBOURNE MELBOURNE'S NEWEST ICON ALEXANDra MELBOURNE COLLINS ST CENTRAL BUSINESS RMIT LYGON ST gardENS MUSEUM SHOppING DISTRICT UNIVERSITY ITALIAN PRECINCT PARLIAMENT ROYAL EXHIBITION CARLTON STATE LIBrary MELBOURNE MELBOURNE STATION BUILDING GARDENS OF VICTORIA CENTral CARLTON UNIVERSITY Artist Impression Johnston St WITH COMMANDING VIEWS UNIVERSITY Grattan St OVER THE CARLTON GARDENS SQUARE AND MELBOURNE'S CBD, UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AND THE CITY’S BEST-KNOWN LINCOLN 60 SQUARE DESTINATIONS AT YOUR Peel St DOORSTEP, THIS IS AN ICONIC Lygon St ARGYLE ADDRESS FOR THE WORLD’S NORTH SQUARE 57 MOST LIVEABLE CITY MELBOURNE Queensberry St Rathdowne St CARLTON UNESCO WORLD Dudley St QUEEN HERITAGE VICTORIA MARKET GARDENS 09 FITZROY 42 FLAGSTAFF GARDENS Gertrude35 St 41 59 36 68 37 RMIT Free City Circle Tram La Trobe St UNIVERSITY RETAIL ARTS, CULTURE Flagsta Melbourne STATE LIBRARY Nicholsont St 39 & ENTERTAINMENT 40 01 Melbourne Central Station Central Victoria Parade 41 Royal Exhibition Building Station 56 13 11 02 Qv Centre Lt Lonsdale St 01 38 03 Emporium 42 Melbourne Esplanade Harbour Museum 58 Wurundjeri Way Wurundjeri Brunswick St MELBOURNE QV 12 Napier St 04 Greek Quarter 43 Her Majesty’s Theatre CENTRAL Parliament 05 Chinatown 44 Princess Theatre 02 Lonsdale St Station Alber t St 06 Bourke St Mall 45 Parliament House 46 Old Treasury Building EMPORIUM 07 St Collins Ln MALL 04 34 08 Luxury Brands 47 Regent Theatre 67 03 43 44 48 Federation Square Lt Bourke St 09 Queen Victoria Market 05 CHINA TOWN