Functions of Foliar Nyctinasty: a Review and Hypothesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1977 A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Lackey, James Andrew, "A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) " (1977). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5832. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5832 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Fruits and Seeds of Genera in the Subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae)

Fruits and Seeds of United States Department of Genera in the Subfamily Agriculture Agricultural Faboideae (Fabaceae) Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1890 Volume I December 2003 United States Department of Agriculture Fruits and Seeds of Agricultural Research Genera in the Subfamily Service Technical Bulletin Faboideae (Fabaceae) Number 1890 Volume I Joseph H. Kirkbride, Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L. Weitzman Fruits of A, Centrolobium paraense E.L.R. Tulasne. B, Laburnum anagyroides F.K. Medikus. C, Adesmia boronoides J.D. Hooker. D, Hippocrepis comosa, C. Linnaeus. E, Campylotropis macrocarpa (A.A. von Bunge) A. Rehder. F, Mucuna urens (C. Linnaeus) F.K. Medikus. G, Phaseolus polystachios (C. Linnaeus) N.L. Britton, E.E. Stern, & F. Poggenburg. H, Medicago orbicularis (C. Linnaeus) B. Bartalini. I, Riedeliella graciliflora H.A.T. Harms. J, Medicago arabica (C. Linnaeus) W. Hudson. Kirkbride is a research botanist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, BARC West Room 304, Building 011A, Beltsville, MD, 20705-2350 (email = [email protected]). Gunn is a botanist (retired) from Brevard, NC (email = [email protected]). Weitzman is a botanist with the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, Washington, DC. Abstract Kirkbride, Joseph H., Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L radicle junction, Crotalarieae, cuticle, Cytiseae, Weitzman. 2003. Fruits and seeds of genera in the subfamily Dalbergieae, Daleeae, dehiscence, DELTA, Desmodieae, Faboideae (Fabaceae). U. S. Department of Agriculture, Dipteryxeae, distribution, embryo, embryonic axis, en- Technical Bulletin No. 1890, 1,212 pp. docarp, endosperm, epicarp, epicotyl, Euchresteae, Fabeae, fracture line, follicle, funiculus, Galegeae, Genisteae, Technical identification of fruits and seeds of the economi- gynophore, halo, Hedysareae, hilar groove, hilar groove cally important legume plant family (Fabaceae or lips, hilum, Hypocalypteae, hypocotyl, indehiscent, Leguminosae) is often required of U.S. -

A Subfamília Faboideae (Fabaceae Lindl.) No Parque Estadual Do Guartelá, Município De Tibagi, Estado Do Paraná

ANNA LUIZA PEREIRA ANDRADE A SUBFAMÍLIA FABOIDEAE (FABACEAE LINDL.) NO PARQUE ESTADUAL DO GUARTELÁ, MUNICÍPIO DE TIBAGI, ESTADO DO PARANÁ Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre, pelo Curso de Pós-Graduação em Ciências - Área Botânica, Setor de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Paraná. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Élide Pereira dos Santos Curitiba - Paraná 2008 ii Dedico este trabalho aos meus pais, Zunir e Eliete, e ao Raphael, que com amor, fizeram com que cada passo da minha vida fosse ainda mais especial. iii AGRADECIMENTOS Desejo dedicar aqui meus sinceros agradecimentos àqueles que, de alguma forma, participaram e colaboraram para a realização deste trabalho. À Universidade Federal do Paraná, e ao Programa de Pós Graduação em Botânica. À Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa por viabilizar o transporte para excursões à área de estudo e infra-estrutura para herborização do material botânico coletado. A CAPES, pela bolsa concedida para a realização deste trabalho. À Profa. Dra. Élide P. dos Santos pela orientação, confiança, sugestões e discussões durante a realização deste trabalho. À Profa. Dra. Marta R. B. do Carmo pela grande ajuda nos trabalhos de campo, pelo incentivo e sugestões, pela amizade e toda a convivência, enfim, por tudo o que me ensinou. À Profa. Dra. Sílvia S. T. Miotto pela recepção na Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, pelo fornecimento de bibliografias, conselhos e sugestões de extrema importância para a realização deste trabalho. Às pessoas mais importantes da minha vida, meus pais Zunir e Eliete, pelo “porto seguro” que sempre representaram na minha vida, por todo o apoio, força, amor e confiança que sempre me dedicaram e que jamais conseguirei retribuir. -

Matk Barcode Database of Legumes

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/241703; this version posted January 1, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. FabElm_BarcodeDb: matK barcode database of legumes Bharat Kumar Mishra , Sakshi Chaudhary, Jeshima Khan Yasin * *corresponding author- [email protected] authors contributed equally Bharat Kumar Mishra†, Division of Genomic Resources ICAR-NBPGR PUSA campus, New Delhi India- 110012 Present address: Department of Biology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, AL, USA AL 35294-1170 [email protected] Sakshi Chaudhary, Division of Genomic Resources ICAR-NBPGR PUSA campus, New Delhi India- 110012 [email protected] Jeshima Khan Yasin * Division of Genomic Resources ICAR-NBPGR PUSA campus, New Delhi India- 110012 [email protected]; [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/241703; this version posted January 1, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract Background DNA barcoding is an imperative implementation of chloroplast rbcL and matK regions exploited as standard molecular barcodes for species identification. MatK is highly conserved in plants and has been used extensively as a phylogenetic marker for classification of plants. In this study matK sequences of Leguminosae were retrieved for variant analysis and phylogentics. -

A New Subfamily Classification of The

LPWG Phylogeny and classification of the Leguminosae TAXON 66 (1) • February 2017: 44–77 A new subfamily classification of the Leguminosae based on a taxonomically comprehensive phylogeny The Legume Phylogeny Working Group (LPWG) Recommended citation: LPWG (2017) This paper is a product of the Legume Phylogeny Working Group, who discussed, debated and agreed on the classification of the Leguminosae presented here, and are listed in alphabetical order. The text, keys and descriptions were written and compiled by a subset of authors indicated by §. Newly generated matK sequences were provided by a subset of authors indicated by *. All listed authors commented on and approved the final manuscript. Nasim Azani,1 Marielle Babineau,2* C. Donovan Bailey,3* Hannah Banks,4 Ariane R. Barbosa,5* Rafael Barbosa Pinto,6* James S. Boatwright,7* Leonardo M. Borges,8* Gillian K. Brown,9* Anne Bruneau,2§* Elisa Candido,6* Domingos Cardoso,10§* Kuo-Fang Chung,11* Ruth P. Clark,4 Adilva de S. Conceição,12* Michael Crisp,13* Paloma Cubas,14* Alfonso Delgado-Salinas,15 Kyle G. Dexter,16* Jeff J. Doyle,17 Jérôme Duminil,18* Ashley N. Egan,19* Manuel de la Estrella,4§* Marcus J. Falcão,20 Dmitry A. Filatov,21* Ana Paula Fortuna-Perez,22* Renée H. Fortunato,23 Edeline Gagnon,2* Peter Gasson,4 Juliana Gastaldello Rando,24* Ana Maria Goulart de Azevedo Tozzi,6 Bee Gunn,13* David Harris,25 Elspeth Haston,25 Julie A. Hawkins,26* Patrick S. Herendeen,27§ Colin E. Hughes,28§* João R.V. Iganci,29* Firouzeh Javadi,30* Sheku Alfred Kanu,31 Shahrokh Kazempour-Osaloo,32* Geoffrey C. -

(Fabaceae Lindl.) No Parque Estadual Do Guartelá, Paraná, Brasil

Hoehnea 36(4): 737-768, 9 fig., 2009 737 A subfamília Faboideae (Fabaceae Lindl.) no Parque Estadual do Guartelá, Paraná, Brasil Anna Luiza Pereira Andrade1, Sílvia Teresinha Sfoggia Miotto2 e Élide Pereira dos Santos1,3 Recebido: 19.06.2008; aceito: 30.12.2009 ABSTRACT - (The subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae Lindl.) in the Parque Estadual do Guartelá, Paraná State, Brazil). This paper consists of asurvey of the Fabaceae subfamily Faboideae in the Parque Estadual do Guartelá, Tibagi, Paraná State, Brazil. Intensive collections were made from October 2006 to October 2007. Thirty-two species and 19 genera of Faboideae were detected. The most diverse genera were Stylosanthes Sw. (five species),Eriosema (DC.) Desv., Crotalaria L. and Desmodium Desv. (three species), Centrosema (DC.) Benth., Machaerium Pers. and Zornia J.F. Gmel. (two species). Aeschynomene L., Camptosema Hook. & Arn., Clitoria L., Collaea DC., Dalbergia L. f., Erythrina L., Galactia P. Br., Indigofera L., Leptolobium Vogel, Ormosia Jacks., Periandra Mart. ex Benth. and Rhynchosia Lour. were each represented by a single species. Descriptions, identification keys, notes and illustrations for the taxa found in the area are provided. Key words: Grassland, Leguminosae, Taxonomy RESUMO - (A subfamília Faboideae (Fabaceae Lindl.) no Parque Estadual do Guartelá, Paraná, Brasil). Este trabalho consiste no levantamento dos representantes de Fabaceae subfamília Faboideae no Parque Estadual do Guartelá (PEG), município de Tibagi, Paraná, Brasil. Foram realizadas coletas mensais no período de outubro de 2006 a outubro de 2007. Trinta e duas espécies e 19 gêneros foram registrados. Os gêneros com maior representatividade foram Stylosanthes Sw. (cinco espécies), Eriosema (DC.) Desv., Crotalaria L. e Desmodium Desv. -

Plant Diversity in Burapha University, Sa Kaeo Campus

doi:10.14457/MSU.res.2019.25 ICoFAB2019 Proceedings | 144 Plant Diversity in Burapha University, Sa Kaeo Campus Chakkrapong Rattamanee*, Sirichet Rattanachittawat and Paitoon Kaewhom Faculty of Agricultural Technology, Burapha University Sa Kaeo Campus, Sa Kaeo 27160, Thailand *Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Plant diversity in Burapha University, Sa Kaeo campus was investigated from June 2016–June 2019. Field expedition and specimen collection was done and deposited at the herbarium of the Faculty of Agricultural Technology. 400 plant species from 271 genera 98 families were identified. Three species were pteridophytes, one species was gymnosperm, and 396 species were angiosperms. Flowering plants were categorized as Magnoliids 7 species in 7 genera 3 families, Monocots 106 species in 58 genera 22 families and Eudicots 283 species in 201 genera 69 families. Fabaceae has the greatest number of species among those flowering plant families. Keywords: Biodiversity, Conservation, Sa Kaeo, Species, Dipterocarp forest Introduction Deciduous dipterocarp forest or dried dipterocarp forest covered 80 percent of the forest area in northeastern Thailand spreads to central and eastern Thailand including Sa Kaeo province in which the elevation is lower than 1,000 meters above sea level, dry and shallow sandy soil. Plant species which are common in this kind of forest, are e.g. Buchanania lanzan, Dipterocarpus intricatus, D. tuberculatus, Shorea obtusa, S. siamensis, Terminalia alata, Gardenia saxatilis and Vietnamosasa pusilla [1]. More than 80 percent of the area of Burapha University, Sa Kaeo campus was still covered by the deciduous dipterocarp forest called ‘Khok Pa Pek’. This 2-square-kilometers forest locates at 13°44' N latitude and 102°17' E longitude in Watana Nakorn district, Sa Kaeo province. -

COPYRIGHT and CITATION CONSIDERATIONS for THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION O Attribution — You Must Give Appropriate Credit, Provide

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012). Title of the thesis or dissertation (Doctoral Thesis / Master’s Dissertation). Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/102000/0002 (Accessed: 22 August 2017). STUDIES ON THE MEDICINALLY IMPORTANT RHYNCHOSIA (PHASEOLEAE, FABACEAE) SPECIES: TAXONOMY, ETHNOBOTANY, PHYTOCHEMISTRY AND ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY BY MASHIANE SONNYBOY MOTHOGOANE Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Botany In Botany and Plant Biotechnology Faculty of Science University of Johannesburg Supervisor: Professor A.N. Moteetee April, 2019 DECLARATION I Mashiane Sonnyboy Mothogoane, declare that this dissertation submitted by me for the degree of Masters in Botany at the Department of Botany and Plant Biotechnology in the Faculty of Science at the University of Johannesburg is my own work in design and execution. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination at this or any other academic institution and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. 15/04/2019 ________________________ _____________________ SIGNATURE DATE (MR M S MOTHOGOANE) i DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this work to my family, parents, Sejeng Magdeline Mothogoane and Mmile William (late) for all the encouragement throughout my school years. -

Microsoft Word

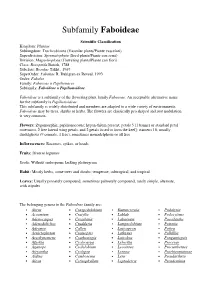

Subfamily Faboideae Scientific Classification Kingdom: Plantae Subkingdom: Tracheobionta (Vascular plants/Piante vascolari) Superdivision: Spermatophyta (Seed plants/Piante con semi) Division: Magnoliophyta (Flowering plants/Piante con fiori) Class: Rosopsida Batsch, 1788 Subclass: Rosidae Takht., 1967 SuperOrder: Fabanae R. Dahlgren ex Reveal, 1993 Order: Fabales Family: Fabaceae o Papilionacee Subfamily: Faboideae o Papilionoideae Faboideae is a subfamily of the flowering plant family Fabaceae . An acceptable alternative name for the subfamily is Papilionoideae . This subfamily is widely distributed and members are adapted to a wide variety of environments. Faboideae may be trees, shrubs or herbs. The flowers are classically pea shaped and root nodulation is very common. Flowers: Zygomorphic, papilionaceous; hypan-thium present; petals 5 [1 banner or standard petal outermost, 2 free lateral wing petals, and 2 petals fused to form the keel]; stamens 10, usually diadelphous (9 connate, 1 free), sometimes monadelphous or all free Inflorescences: Racemes, spikes, or heads Fruits: Diverse legumes Seeds: Without endosperm; lacking pleurogram Habit: Mostly herbs, some trees and shrubs; temperate, subtropical, and tropical Leaves: Usually pinnately compound, sometimes palmately compound, rarely simple, alternate, with stipules The belonging genera to the Faboideae family are: • Abrus • Craspedolobium • Kummerowia • Podalyria • Acosmium • Cratylia • Lablab • Podocytisus • Adenocarpus • Crotalaria • Laburnum • Poecilanthe • Adenodolichos • Cruddasia -

Classification of the Leguminosae-Papilionoideae: a Numerical Re-Assessment

Available online at www.notulaebiologicae.ro Print ISSN 2067-3205; Electronic 2067-3264 Notulae Scientia Biologicae Not Sci Biol, 2013, 5(4):499-507 Classification of the Leguminosae-Papilionoideae: A Numerical Re-assessment Adel EL-GAZZAR1, Monier Abd EL-GHANI2*, Nahed EL-HUSSEINI2, Adel KHATTAB2 1 Department of Biological and Geological Sciences, Faculty of Education, Suez Canal University, N. Sinai, Egypt 2 Department of Botany , Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza 12613, Egypt; [email protected] (*corresponding author) Abstract The subdivision of the Leguminosae-Papilionoideae into taxa of lower rank was subject for major discrepancies between traditional classifications while more recent phylogenetic studies provided no decisive answer to this problem. As a contribution towards resolving this situation, 81 morphological characters were recorded comparatively for 226 species and infra-specific taxa belonging to 75 genera representing 21 of the 32 tribes currently recognized in this subfamily. The data matrix was subjected to cluster analysis using the Sørensen distance measure and Ward’s clustering method of the PC-ord version-5 package of programs for Windows. This combination was selected from among the 56 combinations available in this package because it produced the taxonomically most feasible arrangement of the genera and species. The 75 genera are divided into two main groups A and B, whose recognition requires little more than the re-alignment of a few genera to resemble tribes 1-18 (Sophoreae to Hedysareae) and tribes 19-32 (Loteae to Genisteae), respectively, in the currently accepted classification. Only six of the 21 tribes represented by two or more genera seem sufficiently robust as the genera representing each of them hold together in only one of the two major groups A and B. -

Flowering Plants of Africa 65 (2017) a B Flowering Plants of Africa 65 (2017) Flowering Plants of Africa

Flowering Plants of Africa 65 (2017) a b Flowering Plants of Africa 65 (2017) Flowering Plants of Africa A peer-reviewed journal containing colour plates with descrip- tions of flowering plants of Africa and neighbouring islands Edited by Alicia Grobler with assistance of Gillian Condy Volume 65 Pretoria 2017 ii Flowering Plants of Africa 65 (2017) Editorial board R.R. Klopper South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA P.C. Zietsman National Museum, Bloemfontein, RSA Referees and other co-workers on this volume R.H. Archer, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA S.P. Bester, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA G.J. Bredenkamp, Eco-Agent, Pretoria, RSA G. Germishuizen, ex South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA C.A. González-Martínez, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico A. Grobler, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA D. Goyder, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK L. Henderson, Agricultural Research Council, Pretoria, RSA P.P.J. Herman, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA T.P. Jaca, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA R.R. Klopper, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA M.M. le Roux, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA T. Manyelo, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J.J. Meyer, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA S.M. Mothogoane, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA T. Nkonki, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA T.G. Rebelo, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA E. Retief, ex South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA S.J. Siebert, North-West University, Potchefstroom, RSA V. -

The Bean Bag

The Bean Bag A newsletter to promote communication among research scientists concerned with the systematics of the Leguminosae/Fabaceae Issue 63, Year 2016 CONTENT Page Letter from the Editor 2 Reports of 2016 Happenings 3 A Look into 2017 7 Legume Shots of the Year 10 Legume Bibliography under the Spotlight 12 Publication News from the World of Legume Systematics 14 1 Letter from the Editor Dear Bean Bag Fellow Happy New Year!! My deepest apologies for getting after delay this issue to you. But, as you will very soon see, this is an extra-large issue that needed some extra dedication. It has been a year of many events in the legume world. Starting with the news that past Bean Bag issues are now available online in the BHL repository. Continuing with glimpses from the International Year of Pulses often extended to the entire family, and the looking forward into 2017 where the new legume submfamily classification will be published and a legume symposium is being organized at the International Botanical Congress in China! Then, some beautiful photographs of papilionoid flowers, the highlights from the world of publications on legumes, more special issues available and on the way, and new floristic books. Concluding, as always, with the traditional list of legume bibliography. This is now the second year that the Bean Bag newsletter and important communications have been and still will be sent out through the new BB Google Group to which BB members have been added in 2015. As a reminder, this is the only purpose of the google group.