In Dire Straits ? the State of the Judiciary Report 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Protecting the Human Rights of Sexual Minorities in Contemporary Africa

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315755719 Protecting the human rights of sexual minorities in contemporary Africa Book · April 2017 CITATION READS 1 471 1 author: Sylvie Namwase University of Copenhagen 4 PUBLICATIONS 2 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Children and former child soldiers as victims and perpetrators of international crimes View project Use of force laws in riot control and crimes against humanity under the ICC Statute View project All content following this page was uploaded by Sylvie Namwase on 03 April 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Protecting the human rights of S E X U A L M I N O R I T I E S in contemporary Africa Sylvie Namwase & Adrian Jjuuko (editors) 2017 Protecting the human rights of sexual minorities in contemporary Africa Published by: Pretoria University Law Press (PULP) The Pretoria University Law Press (PULP) is a publisher at the Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa. PULP endeavours to publish and make available innovative, high-quality scholarly texts on law in Africa. PULP also publishes a series of collections of legal documents related to public law in Africa, as well as text books from African countries other than South Africa. This book was peer reviewed prior to publication. For more information on PULP, see www.pulp.up.ac.za Printed and bound by: BusinessPrint, Pretoria To order, contact: PULP Faculty -

Janmyr Civil Militias in Uganda NJHR Aug 2014.Pdf (150.8Kb)

Nordic Journal of Human Rights, 2014 Vol. 32, No. 3, 199–219, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/18918131.2014.937203 Recruiting Internally Displaced Persons into Civil Militias: The Case of Northern Uganda Maja Janmyr* Researcher, Faculty of Law, University of Bergen, Norway This article explores the state-sanctioned recruitment of internally displaced persons (IDPs) into civil militias in northern Uganda between 1996 and 2006. Drawing upon international and Ugandan domestic law, as well as empirical research in Uganda, it provides an illustrative case study of the circumstances in which IDPs were mobilised into an array of civil militias. By applying a framework elaborated by the UN Commission on Human Rights, it discusses, and subsequently determines, the lawfulness of this mobilisation. When doing so, the article highlights how, in Uganda, civil militias were dealt with completely outside of domestic law, despite repeated calls from Ugandan MPs to establish their lawfulness. It finds that government authorities long denied any liability for the conduct of the militias, and argues that the uncertain position of the civil militias created plenty of room for unmonitored conduct and substantial human rights abuse. Keywords: Military recruitment; forced recruitment; civil militia; civil defence forces; auxiliary forces; internally displaced persons; Uganda 1. Introduction Military recruitment in the context of displacement has taken place on almost every continent and constitutes one of the most problematic security issues within refugee and internally displaced persons (IDP) camps.1 Refugees and IDPs have long been recruited by both state and non-state actors, forced or otherwise. At the same time, from the perspective of international law, one form of recruitment – recruitment into civil militias – is particularly understudied. -

The Uganda Law Society 2Nd Annual Rule of Law

THE UGANDA LAW SOCIETY 2ND ANNUAL RULE OF LAW DAY ‘The Rule of Law as a Vehicle for Economic, Social and Political Transformation’ Implemented by Uganda Law Society With Support from Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and DANIDA WORKSHOP REPORT Kampala Serena Hotel 8th October 2009 Kampala – UGANDA 1 Table of Contents T1.T Welcome Remarks – President Uganda Law Society ....................................3 2. Remarks from a Representative of Konrad Adenauer Stiftung...................3 3. Presentation of Main Discussion Paper – Hon. Justice Prof. G. Kanyeihamba............................................................................................................4 4. Discussion of the Paper by Hon. Norbert Mao ...............................................5 5. Discussion of the Paper by Hon. Miria Matembe...........................................6 6. Keynote Address by Hon. Attorney General & Minister of Justice and Constitutional Affairs Representing H.E the President of Uganda. ...................7 7. Plenary Debates .................................................................................................7 8. Closing...............................................................................................................10 9. Annex: Programme 2 1. Welcome Remarks – President Uganda Law Society The Workshop was officially opened by the President of the Uganda Law Society, Mr. Bruce Kyerere. Mr. Kyerere welcomed the participants and gave a brief origin of the celebration of the Rule of Law Day in Uganda. The idea was conceived -

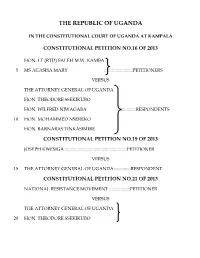

Dissenting Judgment on Expelled NRM

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF UGANDA AT KAMPALA CONSTITUTIONAL PETITION NO.16 OF 2013 HON. LT (RTD) SALEH M.W. KAMBA 5 MS AGASHA MARY :::::::::::::::::::::::::PETITIONERS VERSUS THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF UGANDA HON. THEODORE SSEKIKUBO HON. WILFRED NIWAGABA :::::::::::::::::RESPONDENTS 10 HON. MOHAMMED NSEREKO HON. BARNABAS TINKASIMIRE CONSTITUTIONAL PETITION NO.19 OF 2013 JOSEPH KWESIGA ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::PETITIONER VERSUS 15 THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF UGANDA:::::::::::::::RESPONDENT CONSTITUTIONAL PETITION NO.21 OF 2013 NATIONAL RESISTANCE MOVEMENT ::::::::::::::::::PETITIONER VERSUS THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF UGANDA 20 HON. THEODORE SSEKIKUBO HON. WILFRED NIWAGABA :::::::::::::::::::::RESPONDENTS HON. MOHAMMED NSEREKO HON. BARNABAS TINKASIMIRE 5 CONSTITUTIONAL PETITION NO.25 OF 2013 HON. ABDU KATUNTU :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: PETITIONER VERSUS THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF UGANDA ::::::::::::::::::RESPONDENT CORAM: HON. MR. JUSTICE S.B.K. KAVUMA, AG.DCJ. 10 HON. MR. JUSTICE A.S. NSHIMYE, JA/CC HON. MR. JUSTICE REMMY KASULE, JA/CC HON. LADY JUSTICE FAITH MWONDHA, JA/CC HON. MR. JUSTICE R. BUTEERA, JA/CC DISSENTING JUDGEMENT OF HONOURABLE JUSTICE REMMY 15 KASULE, JUSTICE OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT I am grateful and in agreement with their Lordships of the majority judgement as to the facts constituting the background to the consolidated Constitutional Petitions numbers 16, 19, 21 and 25 of 2013, as well as the principles of constitutional interpretation set out in the said judgement. 2 However, with the greatest respect to their Lordships of the majority judgement, I beg to differ from some of the conclusions they have reached on some of the framed issues. I will, as much as possible deal with the issues following the order they 5 were submitted upon by respective counsel, even though this pattern may be departed from now and then, where the inter-relationship of the issues so demand. -

Office of the Auditor General

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ANNUAL REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2014 VOLUME 2 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT ii Table Of Contents List Of Acronyms And Abreviations ................................................................................................ viii 1.0 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Report And Opinion Of The Auditor General On The Government Of Uganda Consolidated Financial Statements For The Year Ended 30th June, 2014 ....................... 38 Accountability Sector................................................................................................................... 55 3.0 Treasury Operations .......................................................................................................... 55 4.0 Ministry Of Finance, Planning And Economic Development ............................................. 62 5.0 Department Of Ethics And Integrity ................................................................................... 87 Works And Transport Sector ...................................................................................................... 90 6.0 Ministry Of Works And Transport ....................................................................................... 90 Justice Law And Order Sector .................................................................................................. 120 7.0 Ministry Of Justice And Constitutional -

Constitutional & Parliamentary Information

UNION INTERPARLEMENTAIRE INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION CCoonnssttiittuuttiioonnaall && PPaarrlliiaammeennttaarryy IInnffoorrmmaattiioonn Half-yearly Review of the Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments Welcome and presentation on the Vietnamese parliamentary system (NGUYEN Hanh Phuc, Vietnam) Saudi Shura Council Relationship to Society - Hope and Reality (Mohamed AL-AMR, Saudi Arabia) Public Relations of Parliaments: The Case of Turkish Parliament (İrfan NEZİROĞLU, Turkey) Active transparency measures and measures related to citizens right of access to public information in the Spanish Senate (Manuel CAVERO, Spain) The Standing Orders of political parliamentary groups (Christophe PALLEZ, France) Powers and competences of government parties and opposition parties in a multi-party parliament (Geert Jan A. HAMILTON, The Netherlands) Lobbyists and interest groups: the other aspect of the legislative process (General debate) Legislative Consolidation in Portugal: better legislation, closer to the citizens (José Manuel ARAÚJO, Portugal) The formation of government in the Netherlands in 2012 (Geert Jan A. HAMILTON, The Netherlands) When the independence of the Legislature is put on trial: an examination of the dismissal of members of the party in Government from the party vis-à-vis their status in Parliament (Jane L. KIBIRIGE, Uganda) Finding the structure of a parliamentary secretariat with maximum efficiency (General debate) The Committee system in India: Effectiveness in Enforcing Executive Accountability (Anoop MISHRA, India) Review -

Cause List for the Sittings in the Period: 26/08/2013 - 30/08/2013 P

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA In the Court of Appeal of Uganda(COA) at Kampala CIVIL CAUSE LIST FOR THE SITTINGS IN THE PERIOD: 26/08/2013 - 30/08/2013 P. 1 / 13 AUGUST 26, 2013 CORAM: HON. MR. JUSTICE, S.B.K. KAVUMA, JA HON MR. JUSTICE A.S. NSHIMYE, JA HON. MR. JUSTICE REMMY KASULE, JA HON. LADY JUSTICE FAITH E. MWONDHA, JA HON MR. JUSTICE RICHARD BUTEERA, JA Time Case number Parties Claim/Description Sitting type Court/Chamber 109:30 am COA-00-CV-CPC-0016-2013 HON LT (RTD) SALEH M.W KAMBA & ANOR VS MPS who were dismissed from NRM Hearing - COURT1-COA . THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF UGANDA party also to vacate their respective petitioner's case Seats in Parliament. 209:30 am COA-00-CV-CPC-0021-2013 NATIONAL RESISTANCE MOVEMENT VS THE Expelled MPs to retain their seats in Hearing - COURT1-COA . ATTORNEY GENERAL & 4 OTHERS Parliament ontravenes Arts petitioner's case 1(1)(2)(4)2((1)(2),20(1)(2),1 309:30 am COA-00-CV-CPC-0019-2013 JOSEPH KWESIGA VS ATTORNEY GENERAL Declare vacant Seat in Parliament Hearing - . when an elected Member of petitioner's case Parliament is Expelled from Party in acc 409:30 am COA-00-CV-CPC-0025-2013 HON. ABDU KATUNTU VS ATTORNEY GENERAL The Act of the AG advising the Hearing - COURT1-COA . speaker of parliament to expel Mps petitioner's case are in contravation of Article 119 CORAM: HON. MR. JUSTICE KENNETH KAKURU, JA HON. MR. JUSTICE KENNETH KAKURU, JA Time Case number Parties Claim/Description Sitting type Court/Chamber Printed: 23 August 2013 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA In the Court of Appeal of Uganda(COA) at Kampala CIVIL CAUSE LIST FOR THE SITTINGS IN THE PERIOD: 26/08/2013 - 30/08/2013 P. -

THE REPUBLIC of UGANDA in the COURT of APPEAL of UGANDA(COA) at KAMPALA CIVIL REGISTRY CAUSELIST for the SITTINGS of : 27-03-2017 to 31-03-2017

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF UGANDA(COA) AT KAMPALA CIVIL REGISTRY CAUSELIST FOR THE SITTINGS OF : 27-03-2017 to 31-03-2017 MONDAY, 27-MAR-2017 CORAM:: HON. MR JUSTICE S.B.K. KAVUMA, DCJ COURT ROOM :: COURT ROOM1 Time Case number Case Category Pares Charge/Claim Sing Type Posion Hearing Criminal FINANCIAL LOSS-CAUSING UNDER 1. 09:30 COA-00-CR-CP-0112-2016 CHRISTOPHER OBEY VS UGANDA applicant's Applicaons FINANCIAL LOSS HEARING case Hearing Criminal UNDER 2. 09:30 COA-00-CR-CP-0011-2017 LWAMAFA JIMMY VS UGANDA CAUSING FINANCIAL LOSS. applicant's Applicaons HEARING case Hearing Criminal LWAMAZA ERONDA JOHN VS UNDER 3. 09:30 COA-00-CR-CP-0003-2017 MURDER applicant's Applicaons UGANDA HEARING case Hearing Criminal KIWANUKA KUNSA STEPHEN VS UNDER 4. 09:30 COA-00-CR-CP-0004-2017 CAUSING FINANCIAL LOSS. applicant's Applicaons UGANDA HEARING case COURT ROOM :: COURT ROOM CORAM:: HON MR JUSTICE RICHARD BUTEERA, JA 2 HON. MR JUSTICE KENNETH KAKURU, JA HON. JUSTICE ALFONSE OWINY DOLLO, JA Time Case number Case Category Pares Charge/Claim Sing Type Posion Hearing - Elecon Peon TUBO CHRISTIAN NAKWANG VS PENDING 1. 09:30 COA-00-CV-EPP-0080-2016 BRIBERY appellant's Appeals AKELLO ROSE LILLY HEARING case ASSISTANT REGISTRAR BAREEBE ROSEMARY COURT ROOM :: ASSISTANT CORAM:: NGABIRANO REGISTRAR CHAMBERS Time Case number Case Category Pares Charge/Claim Sing Type Posion 1 of 6 THAT THE ADOPTION & PASSING Constuonal MUHUMUZA MOSES VS OF THE KAMPALA CAPITAL CITY Scheduling PENDING 1. 10:00 COA-00-CV-CPC-0001-2015 Peon Cases ATTORNEY GENERAL AUTHORITY TO BORROW $ 175 conference HEARING MILLION ON 19/ 12/ Constuonal MUZANYI YUSUF & 3 OTHERS VS Scheduling PENDING 2. -

DPP Recalls Lwakataka PXUGHU Fioh

8 NEW VISION, Friday, August 1, 2014 NATIONAL NEWS Judiciary denies DPP recalls By Hillary Nsambu The Principal Judge, Yorokamu Bamwine, has dismissed as baseless Lwakataka allegations that there are mafias in the Judiciary. He denied that case files disappear from the Judiciary. Julius Speaking from his chambers at the after High Court main building in Kampala he was on Tuesday, Bamwine refuted admitted allegations that appeared in the media shortly on July 7 quoting High Court judge after the Anup Singh Choudry that there were By Davis Buyondo appealed to the presiding incident. mafias in the Judiciary and that court magistrate to adjourn the case Photo case files get lost. The Director of Public until today, so that the charges by Davis Choudry was referring to a case Prosecutions (DPP), Mike can be read to their client once Buyondo file in which he awarded hundreds Chibita, has recalled a murder again. of millions of shillings to farmers case file on prominent rally But Namazzi of Kaweri Coffee Plantations. He driver Ponsiano Lwakataka for objected to the WANTED requested the Acting Chief Justice, re-examination. request, saying Steven Kavuma, to investigate its According to Rachael Namazzi, the murder wakataka disappearance, saying the farmers the Rakai resident state attorney file might not L is had not been refunded sh20m they and Taban Chiriga, the Rakai be available expected in deposited in court as security for CIID officer, the file has been during that court today. a resident of the same murder file. costs. recalled by the DPP for further time because He is charged Binyobirya village in Fred Kiryowa, Mugambe’s brother, However, Bamwine, who was scrutiny before hearing of the the DPP had with nine Bukomansimbi and said they wanted to know why charges flanked by the chief registrar, Paul case can proceed. -

Chief Justice Katureebe's Key Milestones

Issue 06 | May-July 2016 Chief Justice Katureebe’s key milestones 130 judicial appointments, promotions since 2015 INSIDE Commercial Justice 3,000 cases cleared Litigants recover billions Reports launched through Plea Bargaining as SCP reaches 26 courts President Yoweri Museveni (L) receives the Coat of Arms from Chief Justice, Bart M. Katureebe, after swearing-in as the 12th President of the Republic of Uganda on May 12, 2016. INSIDE... Count your blessings name 2 | Chief Justice Katureebe’s key achievements them one by one 4 | 3,000 cases cleared through Plea Bargaining 6 | The Judicature (Plea Bargain) Rules, 2016 any choose to capitalise on what they do not have in- 8 |CJ explains presidential election petition, Dr. Besigye treason case stead of identifying and celebrating what they have. 10 | 80% of election petitions concluded We, at the Judiciary, love to celebrate our milestones with oomph. We look at achievements as stepping 11 | Meet the new judicial officers Mstones for bigger things. 12 | Commercial Justice Reports launched For the first time, the Judiciary launched two Commercial Justice 13 | Chief Inspector of Courts embarks on countrywide tour Reports to highlight how both the Commercial Division of the High Court and the Small Claims Procedure have been a dream-come-true 14 | Pictorial: Judiciary through the lens for the Ugandan business community. 16 | Judges okay adoption of appellate mediation For Small Claims Procedure (SCP) – now operational in 26 of the 38 17 | Courts to get children’s testimonies by audio video link Magisterial Areas across the country in just three years after its launch 18 | Litigants recover billions as SCP reaches 26 courts – is a success story for both the Judiciary the court users. -

Makerere to Assist Students Search for Jobs by Hannington Mutabazi, Cecilia Okoth Added 19Th January 2019 10:57 AM the Vice Chancellor of Makerere University Prof

Makerere to assist students search for jobs By Hannington Mutabazi, Cecilia Okoth Added 19th January 2019 10:57 AM The Vice Chancellor of Makerere University Prof. Barnabas Nawangwe promised to set up a liaisons desk in his office where they will be able to source employment opportunities for graduates. Former Rubaga South MP, Ken Lukyamuzi was one of graduates. He graduated with a degree in Law at Makerere University on January 18, 2019. Photos by Juliet Kasirye EDUCATION KAMPALA - Makerere University students will move with their heads high since the university has promised to help them in the job hunt, which will help them to combat unemployment. The Vice Chancellor of Makerere University Prof. Barnabas Nawangwe promised to set up a liaisons desk in his office where they will be able to source employment opportunities for graduates. Gen. Andrew Gutti and the Vice Chancellor of Makerere University, Prof. Barnabas Nawangwe in a procession during the last day of the 69th Makerere University graduation ceremony He was presiding over the fourth and last day of the 69th Graduation ceremony of Makerere University on Friday where students from the College of Engineering, Design, Art and Technology (CEDAT), College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CHUSS) and School of Law (LAW) were graduating in various disciplines. Nawangwe who applauded the students for their achievement, advised them to move with ideas ahead of them that will help their communities to shrive. The VC also commented on discipline saying the biggest obstacle to development in the country is the indiscipline of the elites. Former Deputy Chief Justice, Steven Kavuma (2nd right) graduated with a Master’s degree in International Relations and Diplomatic Studies However, he boosted of Makerere having the most disciplined students in the country currently.