Unter-Regional Ties in Costa Rican Prehistoryj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

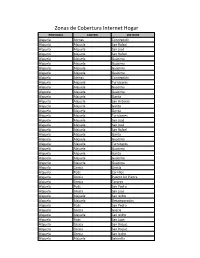

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

Codigo Nombre Dirección Regional Circuito Provincia

CODIGO NOMBRE DIRECCIÓN REGIONAL CIRCUITO PROVINCIA CANTON 0646 BAJO BERMUDEZ PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE ACOSTA 0614 JUNQUILLO ARRIBA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0673 MERCEDES NORTE PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0645 ELOY MORUA CARRILLO PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0689 JOSE ROJAS ALPIZAR PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0706 RAMON BEDOYA MONGE PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0612 SANTA CECILIA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0615 BELLA VISTA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0648 FLORALIA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0702 ROSARIO SALAZAR MARIN PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0605 SAN FRANCISCO PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0611 BAJO BADILLA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0621 JUNQUILLO ABAJO PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0622 CAÑALES ARRIBA PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL JUAN LUIS GARCIA 0624 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL GONZALEZ 0691 SALAZAR PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL DARIO FLORES 0705 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL HERNANDEZ 3997 LICEO DE PURISCAL PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 4163 C.T.P. DE PURISCAL PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL SECCION NOCTURNA 4163 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL C.T.P. DE PURISCAL 4838 NOCTURNO DE PURISCAL PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL CNV. DARIO FLORES 6247 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL HERNANDEZ LICEO NUEVO DE 6714 PURISCAL 01 SAN JOSE PURISCAL PURISCAL 0623 CANDELARITA PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0679 PEDERNAL PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0684 POLKA PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0718 SAN MARTIN PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0608 BAJO LOS MURILLO PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0626 CERBATANA PURISCAL 02 SAN JOSE PURISCAL 0631 -

Municipality of Nicoya the Municipal Council of Nicoya, Approves: As

Date: 30 de diciembre, 2019 This translation was prepared by NCA staff for informational purposes- The NCA assumes no responsibility for any misunderstanding that may occur as a result of this translation. The original document is available upon request. Municipality of Nicoya The Municipal Council of Nicoya, Approves: As established in article 43 of the Municipal Code, publish in the Official Gazette the Draft Regulation for the granting of building permits in the buffer zone of the Ostional National Wildlife Refuge to initiate non-binding public consultation for a period of ten business days, starting the day after the publication in the official Gazette, comments will be received at the email address [email protected]. In exercise of the powers conferred on us by article 50, 89 and 169 of the Political Constitution; the Inter-American Convention for the Protection of Sea Turtles, approved by Law No. 7906 of August 23, 1999, articles 3, 4 subsection 1) and 13 subsection a), c) and p) and 43 of the Municipal Code, Law No. 7794; Articles 15, 19, 20 subsection g) and 21 subsection e) of the Urban Planning Law, Law No. 4240; Articles 28 and 46 of the Organic Law of the Environment, Law No. 7554; and article 11.1, 16 and 113 of the General Law of Public Administration, Law No. 6227, 11 22 and 27 subsection a) of the Biodiversity Law No. 7788, Wildlife Conservation Law, No. 6919, Law of Ostional Wildlife Refuge, No. 9348, Executive Decrees No. 16531-MAG, No. 22551-MIRENEM, and No. 34433-MINAE. Considering: 1º-That Article 50 of the Political Constitution of Costa Rica establishes that the State must guarantee the right of every person to a healthy and ecologically balanced environment. -

Mapa De Valores De Terrenos Por Zonas Homogéneas Provincia 6 Puntarenas Cantón 01 Puntarenas Distrito 11 Cóbano

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 6 PUNTARENAS CANTÓN 01 PUNTARENAS DISTRITO 11 CÓBANO 364000 368500 373000 377500 382000 386500 391000 R í o Q Mapa de Valores de Terrenos B u l e a b n c r a o d por Zonas Homogéneas a Jeringa C Río u b i l Provincia 6 Puntarenas l o R í Q o u S Cantón 01 Puntarenas e b a r n a d Cerro Frío R a a R f A a í Distrito 11 Cóbano tr o e o l c S h o e c Q o Zona Protectora Península de Nicoya - Río Frio Arriba u 1084500 1084500 e b r a d ZONA PROTECTORA PENINSULA DE NICOYA - RIO FRIO ARRIBA a R B ío 6 01 11 R20 í l r o a o F í S n R a n c F a er na n Q LEPANTO d Q o u Q e u u b e r b e a Ministerio de Hacienda r b a r a d d a c a d a e a C Q Q S Órgano de Normalización Técnica D u S a a u a e o a l u e e b l n e d g r t b a d t a a e a d a r r s a a d Y b d V Rí e o a a F a río u d c ZONA PROTECTORA PENINSULA DE NICOYA - CAÑO SECO a a B Q r 6 01 11 R21 u b r e í Río Z o ela BEJUCO u ya Nandayure Plaza a Q Q c PAQUERA Quebrada Vuelta o s uebr æ e ad nm c a S S eca e hancha a rada C S Queb d o a Q r ñ ue b R a br ío e a S C d e u a Pita E co o Q l í Es R p av Quebrada Pita el z aí Queb o R rada Bija Rí gua Zona Protectora Península de Nicoya - Pavones 1080000 Fila Cerital 1080000 ZONA PROTECTORA PENINSULA DE NICOYA - PAVONES 6 01 11 R23 Queb rada B iscoyo l l a t i R r í e o C Cementerio T o u í R í z R Pachanga o o Río RIO FRIO - CAÑO SECO - BAJOS DE ARIO - SAN RAMON - PAVON Q A Vi a ueb s ga Vig 6 01 11 R18/U18 rad tr tero a Pa o Es ZONA PROTECTORA PENINSULA DE NICOYA - PAVON vón B Escuela Pavón la 6 01 11 R22 n nm c Pavón o San Ramón Q nm Cerro Pachanga u o e riceñ b B Q ada r ebr a u u Q d l e oyo a c b o Bis La Angostura r a g V d 0 a ra 6 b n 1 e i l d u a l Q o l ío Pánica n R a a io c B a l Aprobado por: t N S a a o t a í u R Villalta n R Salón La Perla India A n San Antonio t o n Q San Jorge i Ing. -

DREF Operation Costa Rica: Hurricane

DREF Operation Costa Rica: Hurricane Eta DREF Operation MDRCR018 Glide n°: TC-2020-000226-CRI Date of issue: 11 November 2020 Expected timeframe: 3 months Expected end date 28 February 2021 Category allocated to the of the disaster or crisis: Yellow DREF allocated: CHF 345,646 Swiss francs (CHF) Total number of people 25,000 (5,000 families) Number of people to be 7,500 (1,500 families) affected: assisted: Provinces affected: San José, Alajuela, Provinces/Regions Guanacaste, Puntarenas, Heredia, Cartago, targeted: Región Sur1 Puntarenas, Guanacaste, and Limón. Host National Society(ies) presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): The Costa Rican Red Cross (CRRC) has 120 auxiliary committees, 1,147 staff members and some 6,000 volunteers distributed across nine regional offices and the three Headquarters nationwide: Administrative HQ, Operational HQ and Metropolitan Centre HQ. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: National Commission for Risk Prevention and Emergency Care (CNE), 911 Emergency System, Firefighters Brigade, Ministry of Public Infrastructure and Transportation (MOPT), Traffic Police, National Meteorology Institute (IMN), Costa Rican Energy Institute (ICE), Costa Rican Aqueduct and Sewerage Institute (AyA), Municipal Emergency Committees (CME). <Click here for the DREF budget and here for the contact information.> A. Situation analysis Description -

Caracterización Del Territorio

2015 CARACTERIZACIÓN DEL TERRITORIO INSTITUTO DE DESARROLLO RURAL DIRECCION REGION PACIFICO CENTRAL OFICINA SUB-REGIONAL DE OROTINA Tel. 2428-8595 / Fax: 2428-8455 INDICE INDICE .................................................................................................................................................. 1 INDICE DE CUADROS ........................................................................................................................... 9 INDICE DE IMÁGENES ........................................................................................................................ 13 GLOSARIO .......................................................................................................................................... 14 CAPITULO 1. ANTECEDENTES HISTORICOS ....................................................................................... 16 1.1 ANTECEDENTES Y EVOLUCIÓN HISTÓRICA DEL TERRITORIO ........................................ 16 1.1.1 PUNTARENAS.................................................................................................................... 16 1.1.2 MONTES DE ORO .............................................................................................................. 17 1.1.3 MONTE VERDE:................................................................................................................. 19 1.1.4 ISLA CABALLO ................................................................................................................... 22 CAPITULO 2. ASPECTOS BIOFÍSICOS -

Mapa Del Cantón Hojancha 11, Distrito 01

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 5 GUANACASTE CANTÓN 11 HOJANCHA 340000 345000 350000 355000 Mapa de Valores de Terrenos R ío M o Nicoya m o l le Centro Urbano Puerto Carrillo jo por Zonas Homogéneas ESCALA 1:7.500 337500 338000 Provincia 5 Guanacaste Campo de Aterrizaje Cantón 11 Hojancha Esquipulas 5 11 01 U13 s Finca Ponderosa esa a M brad Quebrada Mocosa Ebaisæ Que Plaza nm nm Los Cerrillos 5 11 03 R10/U10 pas Barrio Las Vegas da La ebra 5 11 01 R12/U12 Qu El Tajalin Varillal A San José 1091500 Casa Buena Vista Ministerio de Hacienda es 1115000 Los Ángeles ajon 1115000 uebrada L Fila Matambú nm Q Rest. La Posada Plaza æ La Tropicale Beach Lodge Órgano de Normalización Técnica Cabinas Mary Mirador Hotel Nammbú PUERTO CARRILLO s a í Plaza n 5 11 03 R01/U01 a C 5 11 03 R18/U18 a Cementerio Fuerza Pública d ra 58 a b 1 r le al b u C on e a ci Iglesia Católica Salón Comunal u d a nm ra N Q eb ta æ u Ru Queb Q rada 5 11 03 U04 Arena Quebrada Cristina Aserradero Hotel Guanamar 5 11 01 U03 Parque Salón Comunalnm nm Repuestos Hojancha Finca Ángeles 5 11 01 U02 Q u e 5 11 01 U10 nm 1091000 b 5 11 01 U05 r a nm d 5 11 01 R09/U09 æ Q Villa Oasis a 5 11 01 U01 u Barrio Arena T Fila Pita eb r r o a 5 11 03 R06/U06 j 5 11 01 U04 d a nmPlaza a P il 5 11 01 R06/U06 as Palo de Jabón San Gerardo 5 11 03 R09 Plaza 5 11 01 R08/U08 Q nm u Aprobado por: e b r a d a Viveros Hojancha S.A. -

Nombre Del Comercio Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario

Nombre del Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario comercio Almacén Agrícola Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Cruce Del L-S 7:00am a 6:00 pm Aguas Claras Higuerón Camino A Rio Negro Comercial El Globo Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, contiguo L - S de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 al Banco Nacional p.m. Librería Fox Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, frente al L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Liceo Aguas Claras p.m. Librería Valverde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 500 norte L-D de 7:00 am-8:30 pm de la Escuela Porfirio Ruiz Navarro Minisúper Asecabri Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Las Brisas L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 6:00 400mts este del templo católico p.m. Minisúper Los Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, Cuatro L-D de 6 am-8 pm Amigos Bocas diagonal a la Escuela Puro Verde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Porvenir L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Supermercado 100mts sur del liceo rural El Porvenir p.m. (Upala) Súper Coco Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 300 mts L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 7:00 norte del Bar Atlántico p.m. MINISUPER RIO Alajuela AGUAS ALAJUELA, UPALA , AGUAS CLARAS, L-S DE 7:00AM A 5:00 PM NIÑO CLARAS CUATRO BOCAS 200M ESTE EL LICEO Abastecedor El Alajuela Aguas Zarcas Alajuela, Aguas Zarcas, 25mts norte del L - D de 8:00 a.m. -

Partido Nueva República- Grecia Plan De Gobierno 2020-2024

Partido Nueva República- Grecia Plan de Gobierno 2020-2024 JUNTOS POR NUESTRO CANTÓN SOMOS CAMBIO, SOMOS FUTURO Integrantes Gisela Víquez Cubero, Candidata a la Alcaldía Gilfred Bedford Banton, Candidato a la Primera Vice Alcaldía María del Rocío Madrigal Salazar, Candidata a la Segunda Vice Alcaldía Grecia, Alajuela 14 de Noviembre de 2019. 1 Este trabajo fue elaborado con el aporte de muchas personas a quienes únicamente les ha inspirado el bienestar y progreso de nuestro querido Cantón de Grecia. Incapaces de nombrar a cada uno de ellos en este pequeño espacio, solo nos queda manifestarles a todos, un profundo agradecimiento por este esfuerzo y por poner de lado egoísmos e intereses individuales y unir esfuerzos de manera desinteresada para sacar adelante a nuestra comunidad. 2 Índice CAPITULO I: INTRODUCCIÓN E INDICADORES ................................................ 1 1. BREVE RESEÑA ............................................................................................................ 1 2. INDICADORES MAS RELEVANTES DEL CANTÓN ..................................................... 2 CAPITULO II: JUSTIFICACIÓN PLAN DE GOBIERNO ...................................... 3 3. JUSTIFICACION DEL PLAN DE GOBIERNO ............................................................... 3 3.1 CUADRO DE EJES: PLAN DE GOBIERNO ............................................................................. 7 CAPITULO III: PLANTEAMIENTO Y EJECUCIÓN SEGÚN EJES ................... 8 4. EJE #1: SEGURIDAD CIUDADANA .............................................................................. -

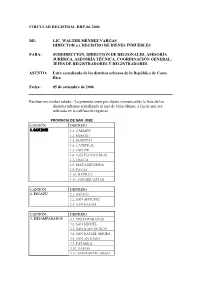

Circular Registral Drp-06-2006

CIRCULAR REGISTRAL DRP-06-2006 DE: LIC. WALTER MÉNDEZ VARGAS DIRECTOR a.i. REGISTRO DE BIENES INMUEBLES PARA: SUBDIRECCIÓN, DIRECCIÓN DE REGIONALES, ASESORÍA JURÍDICA, ASEOSRÍA TÉCNICA, COORDINACIÓN GENERAL, JEFES DE REGISTRADORES Y REGISTRADORES. ASUNTO: Lista actualizada de los distritos urbanos de la República de Costa Rica Fecha: 05 de setiembre de 2006 Reciban mi cordial saludo. La presente tiene por objeto comunicarles la lista de los distritos urbanos actualizada al mes de Julio último, a fin de que sea utilizada en la califiación registral. PROVINCIA DE SAN JOSE CANTÓN DISTRITO 1. SAN JOSE 1.1. CARMEN 1.2. MERCED 1.3. HOSPITAL 1.4. CATEDRAL 1.5. ZAPOTE 1.6. SAN FCO DOS RIOS 1.7. URUCA 1.8. MATA REDONDA 1.9. PAVAS 1.10. HATILLO 1.11. SAN SEBASTIAN CANTÓN DISTRITO 2. ESCAZU 2.1. ESCAZU 2.2. SAN ANTONIO 2.3. SAN RAFAEL CANTÓN DISTRITO 3. DESAMPARADOS 3.1. DESAMPARADOS 3.2. SAN MIGUEL 3.3. SAN JUAN DE DIOS 3.4. SAN RAFAEL ARRIBA 3.5. SAN ANTONIO 3.7. PATARRA 3.10. DAMAS 3.11. SAN RAFAEL ABAJO 3.12. GRAVILIAS CANTÓN DISTRITO 4. PURISCAL 4.1. SANTIAGO CANTÓN DISTRITO 5. TARRAZU 5.1. SAN MARCOS CANTÓN DISTRITO 6. ASERRI 6.1. ASERRI 6.2. TARBACA (PRAGA) 6.3. VUELTA JORCO 6.4. SAN GABRIEL 6.5.LEGUA 6.6. MONTERREY CANTÓN DISTRITO 7. MORA 7.1 COLON CANTÓN DISTRITO 8. GOICOECHEA 8.1.GUADALUPE 8.2. SAN FRANCISCO 8.3. CALLE BLANCOS 8.4. MATA PLATANO 8.5. IPIS 8.6. RANCHO REDONDO CANTÓN DISTRITO 9. -

Mapa De Valores De Terrenos Por Zonas Homogéneas Provincia 4 Heredia Cantón 06 San Isidro

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 4 HEREDIA CANTÓN 06 SAN ISIDRO 494200 497200 Mapa de Valores de Terrenos Centro Urbano de San Isidro por Zonas Homogéneas 1113400 ESCALA 1:2.500 1113400 Provincia 4 Heredia Club del Quesada Autos San Isidro Cantón 06 San Isidro Mini Súper El Paseo Iglesia Cristiana Jesucristo es el Señor a 3 Hogar de Ancianos Alvernia Avenid G Heredia Lavandería Isidrena Abogado y Notario Verdulería La Feria Vázquez de Coronado RÍO TIBÁS NORTE 4 06 01 R07/U07 Ministerio de Hacienda Órgano de Normalización Técnica SAN ISIDRO URBANO Pizzería Napóles Frituras La Teja 4 06 01 U02 EL COLEGIO Finca Helena 4 06 01 R08/U08 z e Abogado y Notario v QUEBRADA CRUCES a h C 4 06 01 R04/U04 Bazar Sami e l s l a Sala de Pooles á C b Moto Decoración i T Megasuper o CEN CINAI Salón Comunal í R Cool Bar El Baúl de AriemArte Tico l Avenida Centra C C a Foto González a l l l l Tienda y Bazar Olga C e e C a C 4 06 03 R07 1 a l l e Iglesia Católica San Isidro l e l n RUTA 112 - SAN ISIDRO e 4 t G r 2 4 06 01 U09 Cancha de Fútbol a Parque Nacional Braulio Carrillo l Aprobado por: Bar El Tenampa Reserva Forestal Cordillera Volcánica Central Café Mil Sabores 4 06 02 R10 Juzgado MUNICIPALIDAD venida 2 Ferretería Frekafa 4 06 01 U24 A Súper Popular Ing. Alberto Poveda Alvarado Director Cadena de Detallistas Comercial Las Delicias 4 06 03 R06 Distribuidora Daniela Órgano Normalización Técnica Depósito San Martín SAN ISIDRO CENTRO Escuela José MartíBanco Nacional n 4 06 01 U01 Picky Puy Restaurante Faisán Dorado Soda La Chozita -

Plan De Desarrollo Distrital, Florencia 2014-2024

Plan de Desarrollo Distrital, Florencia 2014-2024 Contenido AGRADECIMIENTO .............................................................................................................................. 9 PRESENTACIÓN .................................................................................................................................. 10 Miembros de la comisión del Plan de Desarrollo Municipal ............................................................. 12 1 INTRODUCCION .............................................................................................................................. 14 1.1 Naturaleza y Alcance del plan ................................................................................................. 14 1.1.1 Naturaleza ................................................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 Alcance....................................................................................................................................................... 14 2. ASPECTOS GENERALES DEL CANTON ............................................................................................ 15 2.1 Antecedentes sobre su creación, localización geográfica y límites ........................................ 15 2.2 Sinopsis de la historia de San Carlos ....................................................................................... 17 2.3 Sinopsis Geográfica ................................................................................................................