Dutchman's Pipe –Aristolochia Macrophylla Lam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Volume 12 - Number 1 March 2005

Utah Lepidopterist Bulletin of the Utah Lepidopterists' Society Volume 12 - Number 1 March 2005 Extreme Southwest Utah Could See Iridescent Greenish-blue Flashes A Little Bit More Frequently by Col. Clyde F. Gillette Battus philenor (blue pipevine swallowtail) flies in the southern two- thirds of Arizona; in the Grand Canyon (especially at such places as Phantom Ranch 8/25 and Indian Gardens 12/38) and at its rims [(N) 23/75 and (S) 21/69]; in the low valleys of Clark Co., Nevada; and infrequently along the Meadow Valley Wash 7/23 which parallels the Utah/Nevada border in Lincoln Co., Nevada. Since this beautiful butterfly occasionally flies to the west, southwest, and south of Utah's southwest corner, one might expect it to turn up now and then in Utah's Mojave Desert physiographic subsection of the Basin and Range province on the lower southwest slopes of the Beaver Dam Mountains, Battus philenor Blue Pipevine Swallowtail Photo courtesy of Randy L. Emmitt www.rlephoto.com or sporadically fly up the "Dixie Corridor" along the lower Virgin River Valley. Even though both of these Lower Sonoran life zone areas reasons why philenor is not a habitual pipevine species.) Arizona's of Utah offer potentially suitable, resident of Utah's Dixie. But I think interesting plant is Aristolochia "nearby" living conditions for Bat. there is basically only one, and that is watsonii (indianroot pipevine), which phi. philenor, such movements have a complete lack of its larval has alternate leaves shaped like a not often taken place. Or, more foodplants in the region. -

Reconstructing the Basal Angiosperm Phylogeny: Evaluating Information Content of Mitochondrial Genes

55 (4) • November 2006: 837–856 Qiu & al. • Basal angiosperm phylogeny Reconstructing the basal angiosperm phylogeny: evaluating information content of mitochondrial genes Yin-Long Qiu1, Libo Li, Tory A. Hendry, Ruiqi Li, David W. Taylor, Michael J. Issa, Alexander J. Ronen, Mona L. Vekaria & Adam M. White 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, The University Herbarium, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1048, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence). Three mitochondrial (atp1, matR, nad5), four chloroplast (atpB, matK, rbcL, rpoC2), and one nuclear (18S) genes from 162 seed plants, representing all major lineages of gymnosperms and angiosperms, were analyzed together in a supermatrix or in various partitions using likelihood and parsimony methods. The results show that Amborella + Nymphaeales together constitute the first diverging lineage of angiosperms, and that the topology of Amborella alone being sister to all other angiosperms likely represents a local long branch attrac- tion artifact. The monophyly of magnoliids, as well as sister relationships between Magnoliales and Laurales, and between Canellales and Piperales, are all strongly supported. The sister relationship to eudicots of Ceratophyllum is not strongly supported by this study; instead a placement of the genus with Chloranthaceae receives moderate support in the mitochondrial gene analyses. Relationships among magnoliids, monocots, and eudicots remain unresolved. Direct comparisons of analytic results from several data partitions with or without RNA editing sites show that in multigene analyses, RNA editing has no effect on well supported rela- tionships, but minor effect on weakly supported ones. Finally, comparisons of results from separate analyses of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes demonstrate that mitochondrial genes, with overall slower rates of sub- stitution than chloroplast genes, are informative phylogenetic markers, and are particularly suitable for resolv- ing deep relationships. -

Ecological and Evolutionary Consequences of Variation in Aristolochic Acids, a Chemical Resource, for Sequestering Specialist Troidini Butterflies

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2013 Ecological and evolutionary consequences of variation in aristolochic acids, a chemical resource, for sequestering specialist Troidini butterflies Romina Daniela Dimarco University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Dimarco, Romina Daniela, "Ecological and evolutionary consequences of variation in aristolochic acids, a chemical resource, for sequestering specialist Troidini butterflies. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2567 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Romina Daniela Dimarco entitled "Ecological and evolutionary consequences of variation in aristolochic acids, a chemical resource, for sequestering specialist Troidini butterflies." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. James -

Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees

Selecting juglone-tolerant plants Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees Black walnut trees (Juglans nigra) can be very attractive in the home landscape when grown as shade trees, reaching a potential height of 100 feet. The walnuts they produce are a food source for squirrels, other wildlife and people as well. However, whether a black walnut tree already exists on your property or you are considering planting one, be aware that black walnuts produce juglone. This is a natural but toxic chemical they produce to reduce competition for resources from other plants. This natural self-defense mechanism can be harmful to nearby plants causing “walnut wilt.” Having a walnut tree in your landscape, however, certainly does not mean the landscape will be barren. Not all plants are sensitive to juglone. Many trees, vines, shrubs, ground covers, annuals and perennials will grow and even thrive in close proximity to a walnut tree. Production and Effect of Juglone Toxicity Juglone, which occurs in all parts of the black walnut tree, can affect other plants by several means: Stems Through root contact Leaves Through leakage or decay in the soil Through falling and decaying leaves When rain leaches and drips juglone from leaves Nuts and hulls and branches onto plants below. Juglone is most concentrated in the buds, nut hulls and All parts of the black walnut tree produce roots and, to a lesser degree, in leaves and stems. Plants toxic juglone to varying degrees. located beneath the canopy of walnut trees are most at risk. In general, the toxic zone around a mature walnut tree is within 50 to 60 feet of the trunk, but can extend to 80 feet. -

Native Plants for Wildlife Habitat and Conservation Landscaping Chesapeake Bay Watershed Acknowledgments

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Native Plants for Wildlife Habitat and Conservation Landscaping Chesapeake Bay Watershed Acknowledgments Contributors: Printing was made possible through the generous funding from Adkins Arboretum; Baltimore County Department of Environmental Protection and Resource Management; Chesapeake Bay Trust; Irvine Natural Science Center; Maryland Native Plant Society; National Fish and Wildlife Foundation; The Nature Conservancy, Maryland-DC Chapter; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center; and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office. Reviewers: species included in this guide were reviewed by the following authorities regarding native range, appropriateness for use in individual states, and availability in the nursery trade: Rodney Bartgis, The Nature Conservancy, West Virginia. Ashton Berdine, The Nature Conservancy, West Virginia. Chris Firestone, Bureau of Forestry, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Chris Frye, State Botanist, Wildlife and Heritage Service, Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Mike Hollins, Sylva Native Nursery & Seed Co. William A. McAvoy, Delaware Natural Heritage Program, Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Mary Pat Rowan, Landscape Architect, Maryland Native Plant Society. Rod Simmons, Maryland Native Plant Society. Alison Sterling, Wildlife Resources Section, West Virginia Department of Natural Resources. Troy Weldy, Associate Botanist, New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Graphic Design and Layout: Laurie Hewitt, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office. Special thanks to: Volunteer Carole Jelich; Christopher F. Miller, Regional Plant Materials Specialist, Natural Resource Conservation Service; and R. Harrison Weigand, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Maryland Wildlife and Heritage Division for assistance throughout this project. -

An Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials This Page Intentionally Left Blank an Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials

An Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials This page intentionally left blank An Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials W. George Schmid Timber Press Portland • Cambridge All photographs are by the author unless otherwise noted. Copyright © 2002 by W. George Schmid. All rights reserved. Published in 2002 by Timber Press, Inc. Timber Press The Haseltine Building 2 Station Road 133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite 450 Swavesey Portland, Oregon 97204, U.S.A. Cambridge CB4 5QJ, U.K. ISBN 0-88192-549-7 Printed in Hong Kong Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schmid, Wolfram George. An encyclopedia of shade perennials / W. George Schmid. p. cm. ISBN 0-88192-549-7 1. Perennials—Encyclopedias. 2. Shade-tolerant plants—Encyclopedias. I. Title. SB434 .S297 2002 635.9′32′03—dc21 2002020456 I dedicate this book to the greatest treasure in my life, my family: Hildegarde, my wife, friend, and supporter for over half a century, and my children, Michael, Henry, Hildegarde, Wilhelmina, and Siegfried, who with their mates have given us ten grandchildren whose eyes not only see but also appreciate nature’s riches. Their combined love and encouragement made this book possible. This page intentionally left blank Contents Foreword by Allan M. Armitage 9 Acknowledgments 10 Part 1. The Shady Garden 11 1. A Personal Outlook 13 2. Fated Shade 17 3. Practical Thoughts 27 4. Plants Assigned 45 Part 2. Perennials for the Shady Garden A–Z 55 Plant Sources 339 U.S. Department of Agriculture Hardiness Zone Map 342 Index of Plant Names 343 Color photographs follow page 176 7 This page intentionally left blank Foreword As I read George Schmid’s book, I am reminded that all gardeners are kindred in spirit and that— regardless of their roots or knowledge—the gardening they do and the gardens they create are always personal. -

Fv{Âçä~|ÄÄ Géãçá{|Ñ CHESTER COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA

fv{âçÄ~|ÄÄ gÉãÇá{|Ñ CHESTER COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA cxÇÇáçÄätÇ|t fàtàx YÄÉãxÜ `ÉâÇàt|Ç _tâÜxÄ NATIVE PLANT LIST A RESIDENT’S GUIDE 2017 fv{âçÄ~|ÄÄ gÉãÇá{|Ñ CHESTER COUNTY NATIVE PLANT LIST A Resident’s Guide Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 So what exactly is a Native Plant? ................................................................. 1 Go native with these 6 basics: ........................................................................ 2 In Summary ....................................................................................................... 4 NATIVE PLANT LIST OVERVIEW ............................................................................. 5 TREES ................................................................................................................. 6 EVERGREEN ................................................................................................... 6 DECIDUOUS ................................................................................................... 6 FLOWERING ................................................................................................... 7 SHRUBS .............................................................................................................. 8 EVERGREEN ................................................................................................... 8 DECIDUOUS .................................................................................................. -

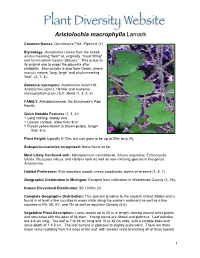

Aristmacr ARIS FINAL

Aristolochia macrophylla Lamark Common Names: Dutchman’s Pipe, Pipevine (1) Etymology: Aristolochia comes from the Greek aristos meaning "best" or, originally, "most fitting" and lochia which means “delivery.” This is due to its original use to expel the placenta after childbirth. Macrophylla is also from Greek, where macros means “long, large” and phylo meaning “leaf” (4, 7, 8). Botanical synonyms: Aristolochia durior Hill, Aristolochia sipho L’Heritier and Isotrema macrophyllum (Lam.) C.F. Reed (1, 3, 4, 5). FAMILY: Aristolochiaceae, the Dutchman’s Pipe Family Quick Notable Features (1, 3, 4): ¬ Long twining, woody vine ¬ Leaves cordate, wider than 9cm ¬ Flower yellow-brown to brown-purple, longer than 3cm. Plant Height: typically 5-10m, but can grow to be up to 20m long (9). Subspecies/varieties recognized: None found so far. Most Likely Confused with: Menispermum canadaense, SIcyos angulatus, Echinocystis lobata, Dioscorea villosa, and Hedera helix as well as non-climbing species in the genus Aristolochia. Habitat Preference: Rich mountain woods, mesic woodlands, banks of streams (1, 6, 7). Geographic Distribution in Michigan: Escaped from cultivation in Washtenaw County (3, 16). Known Elevational Distribution: 50-1300m (4) Complete Geographic Distribution: This species is native to the eastern United States and is found in at least a few counties in every state along the eastern seaboard as well as a few counties in PA, MI, KY, and TN as well as southern Ontario (5,6). Vegetative Plant Description: Liana, woody up to 20 m in length, twining around other plants and structures with the apex of its stem. Young stems are ribbed and glabrous. -

Plants of the Cherokee and Their Uses

PLANTS OF THE CHEROKEE AND THEIR USES Hannah Dinkins Western Carolina University “Each Tree, Shrub, and Herb down to the Grasses and Mosses, agreed to furnish a cure for some one of the diseases named and each said: ‘I shall appear to help Man when he calls upon me in his need’”. ~ Moony History between the land and the Cherokee people the past, present and future. Historically The Cherokee lands were comprised of eight states which ranged as far north as Kentucky and as far south as Georgia and expanded as far east and west as North Carolina to Tennessee. The Cherokee people believe they have lived in this region of the Appalachian Mountains since the beginning of time, because to them all life began here. The original mother town was known as Kituwah, it determined where all Cherokee life and law came from. Scientifically, Archaeologist thought the Cherokee people have been evident in this area for 1200 years, which coincided with the Barren Straight theory. However, current archaeologist digs have provided them with artifacts which support that Cherokee people have been here for at least 1400-1500 years. The Cherokee people historically had a close vital connection to the land. Cherokee diet consisted of a diverse amount of plants, plants were used for foods, medicine and clothing. Cherokee people never had any domesticated animals except for a dog, this was due to how well they managed their natural resource and landscape. The landscape would be manipulated and managed to make mosaic green-ways that allowed them easy availability to animals for hunting purposes, most of their hunting grounds were in Kentucky and Virginia. -

Polydamas Swallowtail, Gold Rim, Tailless Swallowtail, Battus Polydamas Lucayus (Rothschild & Jordan) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Papilionidae: Troidini)1 Donald W

EENY-062 Polydamas Swallowtail, Gold Rim, Tailless Swallowtail, Battus polydamas lucayus (Rothschild & Jordan) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Papilionidae: Troidini)1 Donald W. Hall2 Introduction The name Battus is from Battus I, founder of the ancient Greek colony Cyrenaica and its capital, Cyrene, in Africa. The Polydamas swallowtail is one of only two US swal- The specific epithet polydamas is from Polydamas, a charac- lowtails of the genus Battus. It is our only US swallowtail ter from Greek mythology (Opler and Krizek 1984). without tails (Figure 1). Larvae of the Polydamas swallowtail and those of the other swallowtails belonging to the tribe Troidini feed exclusively on plants in the genus Aristolochia and are commonly referred to as the Aristolochia swallowtails. Distribution In the United States, Battus polydamas lucayus occurs as a regular resident in peninsular Florida and the Florida Keys, and occasional strays wander to other Gulf states and as far north as Missouri and Kentucky (Scott 1986). Subspe- cies polydamas occurs in southern Texas (Figure 2) (dos Figure 1. Polydamas swallowtail (Battus polydamas lucayus [Rothschild Passos 1940). & Jordan]). Credits: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS Nomenclature The Polydamas swallowtail was originally described and named Papilio polydamas by Linnaeus but was later transferred to the genus Battus (Scopoli 1777) and selected as type species of the genus by Lindsey (1925). 1. This document is EENY-062, one of a series of the Entomology and Nematology Department, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date November 1998. Revised July 2010, August 2011, October 2015, August 2016, March 2017 and March 2020. Visit the EDIS website at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. -

Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas Revised & Updated – with More Species and Expanded Control Guidance

Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas Revised & Updated – with More Species and Expanded Control Guidance National Park Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1 I N C H E S 2 Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas, 4th ed. Authors Jil Swearingen National Park Service National Capital Region Center for Urban Ecology 4598 MacArthur Blvd., N.W. Washington, DC 20007 Britt Slattery, Kathryn Reshetiloff and Susan Zwicker U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Chesapeake Bay Field Office 177 Admiral Cochrane Dr. Annapolis, MD 21401 Citation Swearingen, J., B. Slattery, K. Reshetiloff, and S. Zwicker. 2010. Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas, 4th ed. National Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Washington, DC. 168pp. 1st edition, 2002 2nd edition, 2004 3rd edition, 2006 4th edition, 2010 1 Acknowledgements Graphic Design and Layout Olivia Kwong, Plant Conservation Alliance & Center for Plant Conservation, Washington, DC Laurie Hewitt, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office, Annapolis, MD Acknowledgements Funding provided by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation with matching contributions by: Chesapeake Bay Foundation Chesapeake Bay Trust City of Bowie, Maryland Maryland Department of Natural Resources Mid-Atlantic Invasive Plant Council National Capital Area Garden Clubs Plant Conservation Alliance The Nature Conservancy, Maryland–DC Chapter Worcester County, Maryland, Department of Comprehensive Planning Additional Fact Sheet Contributors Laurie Anne Albrecht (jetbead) Peter Bergstrom (European