Principles of Syndicalism - Tom Brown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union Security and the Right to Work Laws: Is Coexistence Possible?

William & Mary Law Review Volume 2 (1959-1960) Issue 1 Article 3 October 1959 Union Security and the Right to Work Laws: Is Coexistence Possible? J. T. Cutler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons Repository Citation J. T. Cutler, Union Security and the Right to Work Laws: Is Coexistence Possible?, 2 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 16 (1959), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol2/iss1/3 Copyright c 1959 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr UNION SECURITY AND RIGHT-TO-WORK LAWS: IS CO-EXISTENCE POSSIBLE? J. T. CUTLER THE UNION STRUGGLE At the beginning of the 20th Century management was all powerful and with the decision in Adair v. United States1 it seemed as though Congress was helpless to regulate labor relations. The Supreme Court had held that the power to regulate commerce could not be applied to the labor field because of the conflict with fundamental rights secured by the Fifth Amendment. Moreover, an employer could require a person to agree not to join a union as a condition of his employment and any legislative interference with such an agreement would be an arbitrary and unjustifiable infringement of the liberty of contract. It was not until the first World War that the federal government successfully entered the field of industrial rela- tions with the creation by President Wilson of the War Labor Board. Upon being organized the Board adopted a policy for- bidding employer interference with the right of employees to organize and bargain collectively and employer discrimination against employees engaging in lawful union activities2 . -

Governing Body 323Rd Session, Geneva, 12–27 March 2015 GB.323/INS/5/Appendix III

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE Governing Body 323rd Session, Geneva, 12–27 March 2015 GB.323/INS/5/Appendix III Institutional Section INS Date: 13 March 2015 Original: English FIFTH ITEM ON THE AGENDA The Standards Initiative – Appendix III Background document for the Tripartite Meeting on the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87), in relation to the right to strike and the modalities and practices of strike action at national level (revised) (Geneva, 23–25 February 2015) Contents Page Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Decision on the fifth item on the agenda: The standards initiative: Follow-up to the 2012 ILC Committee on the Application of Standards .................. 1 Part I. ILO Convention No. 87 and the right to strike ..................................................................... 3 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 3 II. The Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention, 1948 (No. 87) ......................................................................... 3 II.1. Negotiating history prior to the adoption of the Convention ........................... 3 II.2. Related developments after the adoption of the Convention ........................... 5 III. Supervision of obligations arising under or relating to Conventions ........................ -

Collective Bargaining Agreement the Regional Transportation District

Collective Bargaining Agreement 2018-2021 by and between The Regional Transportation District David A. Genova, General Manager and CEO and Amalgamated Transit Union Local 1001 Julio X. Rivera, President and Business Agent TABLE OF CONTENTS MASTER AGREEMENT ............................................................................................... 10 ARTICLE I ..................................................................................................................... 10 GENERAL PROVISIONS ............................................................................................. 10 SECTION 1 ................................................................................................................... 10 MANAGEMENT-UNION RELATIONS .......................................................................... 10 SECTION 2 ................................................................................................................... 10 TERM OF AGREEMENT .............................................................................................. 10 SECTION 3 ................................................................................................................... 11 RECOGNITION AND BARGAINING UNIT ................................................................... 11 SECTION 4 ................................................................................................................... 11 ADDITIONAL AGREEMENTS BETWEEN THE PARTIES .......................................... 11 SECTION 5 .................................................................................................................. -

The Framework of Democracy in Union Government

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 1982 The Framework of Democracy in Union Government Roger C. Hartley The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Labor and Employment Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Roger C. Hartley, The Framework of Democracy in Union Government, 32 CATH. U. L. REV. 13 (1982). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FRAMEWORK OF DEMOCRACY IN UNION GOVERNMENT* Roger C. Hartley** TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ................................................. 15 II. Broad Contours of the Framework .......................... 18 A. The Dual Union Governments .......................... 18 B. Causes of Doctrinal Fragmentation ...................... 20 III. Unions' Assigned Societal Functions ......................... 26 A. The Roots of Ambivalence .............................. 26 1. English and Colonial American Historical and Legal Precedent ............................................ 26 2. Competing Values Raised in the Conspiracy Trials 28 B. Subsequent Forces Conditioning the Right to Assert G roup Interests ......................................... 30 1. Informal Worker Control of Group Conduct ......... 31 2. The Development of Business Unionism ............. 32 a. Worker Political Movements ..................... 32 b. Cooperative Movements .......................... 32 c. The Ascendancy of the Union Movement ........ 33 3. Recognition of the Need for Unions as a Countervailing Force ................................ 34 a. Emergence of Corporate Power ................. -

Michigan Laborlabor Law:Law: Whatwhat Everyevery Citizencitizen Shouldshould Knowknow

August 1999 A Mackinac Center Report MichiganMichigan LaborLabor Law:Law: WhatWhat EveryEvery CitizenCitizen ShouldShould KnowKnow by Robert P. Hunter, J. D., L L. M Workers’ and Employers’ Rights and Responsibilities, and Recommendations for a More Government-Neutral Approach to Labor Relations The Mackinac Center for Public Policy is a nonpartisan research and educational organization devoted to improving the quality of life for all Michigan citizens by promoting sound solutions to state and local policy questions. The Mackinac Center assists policy makers, scholars, business people, the media, and the public by providing objective analysis of Michigan issues. The goal of all Center reports, commentaries, and educational programs is to equip Michigan citizens and other decision makers to better evaluate policy options. The Mackinac Center for Public Policy is broadening the debate on issues that has for many years been dominated by the belief that government intervention should be the standard solution. Center publications and programs, in contrast, offer an integrated and comprehensive approach that considers: All Institutions. The Center examines the important role of voluntary associations, business, community and family, as well as government. All People. Mackinac Center research recognizes the diversity of Michigan citizens and treats them as individuals with unique backgrounds, circumstances, and goals. All Disciplines. Center research incorporates the best understanding of economics, science, law, psychology, history, and morality, moving beyond mechanical cost/benefit analysis. All Times. Center research evaluates long-term consequences, not simply short-term impact. Committed to its independence, the Mackinac Center for Public Policy neither seeks nor accepts any government funding. It enjoys the support of foundations, individuals, and businesses who share a concern for Michigan’s future and recognize the important role of sound ideas. -

Issue No. 45, August, 1977

NUMBER 45 AUGUST 1977 TWENTY CENTS Defend pickets, bans, closed shops o Ilrightll to scab!I From the massive open-cut mines of t·he Pilbara to rai sed by the SUA) working shorter hours at no loss in the wharves of Queensland, the recent outbreak of pay plus full parity at the highest international level. class battles has manifested the bourgeoisie~s deter The legislative attacks on union rights have been mination to cripple the trade-union movement. The tory accompanied by an increasingly shrill propaganda cam governments of Charles Court in West Australia and Joh paign to whip up pOPlliar anti-union sentiment. During Bjelke-Petersen in Queensl and have spearheaded a the Mt Newman strike in West Australia, Court sent let deliberate campaign of open provocation and repressive ters to every householder in the Pilbara encouraging legislation designed to strip organised labour of its their involvement in "restoring industrial peace" -- at only effective weapon against the bosses: the ability a government eXPense of over $800! Following mass to organise and effect a shutdown of production. The union mobilisationsin defence of the arrested Fre closed shop and the right to picket have been threat mantle pi cketers, over 2000 avowedly middl e-class ened by legislative attacks and a barrage of propaganda marchers, organised by a liberal Party member, demon in the bosses' press aimed at mobilising an anti-union strated against "irresponsible unionism" in Perth. And hysteria and glorifying common scabs as heroic "rebels" during the Fremantle conflict, a little-known Women's and "victims" of the "powerful", "militant" unions. -

1.3 Recent Board & Department of Labor Activity on Union Organizing

ABOUT THE AUTHORS Michael G. Pedhirney is a shareholder in the San Francisco office of Littler Mendelson, P.C., the largest U.S.-based law firm exclusively devoted to representing management in labor and employment law. Michael focuses on the representation of management in a broad range of labor and employment law matters, particularly collective bargaining and matters before the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). In addition to appearing in state and federal courts and before the NLRB, Michael also represents employers in collective bargaining and handles arbitrations and mediations. Karen A. Sundermier, in her current role as a Knowledge Management Counsel for Littler, helped design Littler LaborSmart™, an interactive, online tool that allows in-house legal and labor relations professionals to access all of their company’s collective bargaining agreements in a structured, searchable database. The tool allows companies to swiftly identify and compare language for contract administration, grievance, and negotiation purposes. Prior to turning her focus to offering strategic and innovative legal service solutions, Karen represented employers in a broad spectrum of employment and labor matters and assisted employers with representation elections and collective bargaining as a Littler associate and in- house employment counsel. She currently serves as an editor for Littler’s publications on labor relations topics. © 2018 LITTLER MENDELSON, P.C. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. i COVERAGE Scope of Discussion. This publication explains union election procedures and the NLRB’s role in overseeing elections. It also explores NLRB precedent on objectionable conduct by different parties that may result in election results being overturned. Also included is information concerning actions employers are permitted to take and are prohibited from taking in advance of and in response to union organizing drives. -

Waiver of Beck Rights and Resignation Rights: Infusing the Union- Member Relationship with Individualized Commitment

Catholic University Law Review Volume 43 Issue 1 Fall 1993 Article 6 1993 Waiver of Beck Rights and Resignation Rights: Infusing the Union- Member Relationship With Individualized Commitment Heidi Marie Werntz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Heidi M. Werntz, Waiver of Beck Rights and Resignation Rights: Infusing the Union-Member Relationship With Individualized Commitment, 43 Cath. U. L. Rev. 159 (1994). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol43/iss1/6 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS WAIVER OF BECK RIGHTS AND RESIGNATION RIGHTS: INFUSING THE UNION-MEMBER RELATIONSHIP WITH INDIVIDUALIZED COMMITMENT* "[T]he struggle of man against power has been the struggle of memory against forgetting."1 Traditionally, the obligation to pay dues' has been considered to arise from only two sources: union membership3 and union security agree- ments.4 Union membership requires the employee to contribute dues in * First Place, John H. Fanning Labor Law Writing Competition, Columbus School of Law, the Catholic University of America, 1992. 1. MILAN KUNDERA, THE BOOK OF LAUGHTER AND FORGETrING 3 (Michael H. Heim trans., Penguin Books 1986) (1978). 2. Unions garner the bulk of their revenue from the payment of dues and assess- ments by the employees they represent. See Jennifer Friesen, The Costs of "Free Speech"-Restrictions on the Use of Union Dues to Fund New Organizing, 15 HAsTINGS CONST. -

NFIB Guide to Managing Unionization Efforts | One

www.NFIB.com/unionizationguide nFIB guIde to ManagIng unIonIzatIon eFForts 1. What to Do When Facing an Organizing de I Campaign » Know your rights » Understand the National Labor Relations Act » Be familiar with the National Labor Relations Board What’s Ins 2. Allowing Unions Access to Your Employees ✔ » Rules regarding the solicitation of your employees » Distribution of pro-union materials 3. What You Can Say to Your Employees » Communicating the disadvantages of union membership » Talking about strikes 4. What You Cannot Say to Your Employees » Consider their perspective » Six guidelines to remember 5. What to Do When Your Rights the Union Arrives » Avoid costly missteps During a Union Organizing Campaign DEVELOPED BY SMALL BUSINESS LEGAL CENTER www.NFIB.com/unionizationguide A Message from the President Dear NFIB Member: ✔ With membership on the decline for decades, unions are scrambling to boost their numbers any way they can. More than ever before, unions are targeting small and independent businesses. Expedited election regulations, mandatory paid time off and expansion of the Family Medical Leave Act are big ticket items with which they hope to turn the tide back in their favor. We are the leading voice fighting these initiatives. We believe that you should be free to offer the policies and benefit plans that best suit your business and your employees. We believe that one-size-fits-all employment policies don’t work for small businesses. You need flexible workplace policies to juggle your em- aBout nFIB guIde to ManagIng ployees’ needs, as well as your own. unIonIzatIon eFForts To help you, the NFIB Small Business Legal Center has developed Our third installation in a series of guides for small the NFIB Guide to Labor Relations: Your Rights During a Union businesses, the NFIB Guide to Managing Unionization Organizing Campaign, where you’ll discover information on what Efforts features information on what to do when facing to do when facing unionization, including when and where unions unionization. -

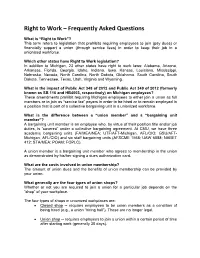

Right to Work – Frequently Asked Questions

Right to Work – Frequently Asked Questions What is “Right to Work”? This term refers to legislation that prohibits requiring employees to join (pay dues) or financially support a union (through service fees) in order to keep their job in a unionized workforce. Which other states have Right to Work legislation? In addition to Michigan, 23 other states have right to work laws: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia and Wyoming. What is the impact of Public Act 348 of 2012 and Public Act 349 of 2012 (formerly known as SB 116 and HB4003, respectively) on Michigan employees? These amendments prohibit requiring Michigan employees to either join a union as full members or to join as “service fee” payers in order to be hired or to remain employed in a position that is part of a collective bargaining unit in a unionized workforce. What is the difference between a “union member” and a “bargaining unit member”? A bargaining unit member is an employee who, by virtue of their position title and/or job duties, is “covered” under a collective bargaining agreement. At CMU, we have three academic bargaining units (FA/MEA/NEA; UTF/AFT-Michigan, AFL/CIO; GSU/AFT- Michigan, AFL/CIO) and six staff bargaining units (AFSCME 1568; UAW 6888; NABET 412; STA/MEA; POAM; FOPLC). A union member is a bargaining unit member who agrees to membership in the union as demonstrated by his/her signing a dues authorization card. -

Union Checkoff Arrangements Under the National Labor Relations Act

DePaul Law Review Volume 39 Issue 3 Spring 1990 Article 4 Union Checkoff Arrangements under the National Labor Relations Act Thomas R. Haggard Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Thomas R. Haggard, Union Checkoff Arrangements under the National Labor Relations Act , 39 DePaul L. Rev. 567 (1990) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol39/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNION CHECKOFF ARRANGEMENTS UNDER THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS ACT Thomas R. Haggard TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION, BACKGROUND, AND OVERVIEW ..................... 568 A. Checkoff Arrangements and Union Security .................569 B. Nature of the Legal Relationship ................................. 571 C. The Relative Importance of the Checkoff to Unions and E mployers ................................................................ 574 II. SECTION 302 REQUIREMENTS ............................................... 575 A. What May Be Checked-Off ........................................ 577 B. Limits on the Right to Revoke .................................... 578 1. Renewal of Authorization .................................... 578 2. Hiatus of Collective Bargaining Agreement ............580 C. Enforcement Mechanisms .......................................... -

Union Security Agreements in Public Employment Patricia N

Cornell Law Review Volume 60 Article 2 Issue 2 January 1975 Union Security Agreements in Public Employment Patricia N. Blair Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Patricia N. Blair, Union Security Agreements in Public Employment, 60 Cornell L. Rev. 183 (1975) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol60/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNION SECURITY AGREEMENTS IN PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT Patricia N. Blairt The number of employees on the public payroll has more than doubled in the past two decades.' Public employee union member- ship has exhibited a commensurate growth record. 2 The recogni- tion by federal and state governments of the right of public employees to bargain collectively has increased correspondingly. Although such uniform national legislation as the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA)3 and the Railway Labor Act of 1926 (RLA),4 which guarantee the right to bargain collectively in the private sector, has no counterpart in the area of public employ- ment, both the federal government and a substantial majority of the states have acted to secure collective bargaining rights for their respective public employees. At the federal level, Executive Order Number 11,4915 and the Postal Reorganization Act of 19706 guarantee United States employees7 the right to bargain collectively.