Shortcomings of the EU State Aid Model from Peripheral Perspective: the Case of Estonian Air

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air Transport Industry Analysis Report

Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2016 Final Report March 2017 European Commission Annual Analyses related to the EU Air Transport Market 2016 328131 ITD ITA 1 F Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2013 Final Report March 2015 Annual Analyses of the EU Air Transport Market 2013 MarchFinal Report 201 7 European Commission European Commission Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate General for Mobility and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract MOVE/E1/5-2010/SI2.579402. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the European Commission's or the Mobility and Transport DG's views. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the information given in the report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. Copyright in this report is held by the European Communities. Persons wishing to use the contents of this report (in whole or in part) for purposes other than their personal use are invited to submit a written request to the following address: European Commission - DG MOVE - Library (DM28, 0/36) - B-1049 Brussels e-mail (http://ec.europa.eu/transport/contact/index_en.htm) Mott MacDonald, Mott MacDonald House, 8-10 Sydenham Road, Croydon CR0 2EE, United Kingdom T +44 (0)20 8774 2000 F +44 (0)20 8681 5706 W www.mottmac.com Issue and revision record StandardSta Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description ndard A 28.03.17 Various K. -

Services Digital

U-SPACE Digital cloudservices Accelerating Estonian U-space as drone usage soars he economic potential of All airspace users must be aware of one multiple drone use cases; from parcel drones is boundless; as Europe another and be contactable. deliveries to search and rescue. announces the adoption of Worldwide, ANSPs are keen to solve The key has always been the integration U-space drone regulations, this dilemma and profit from the clear of air traffic management (ATM) and Maria Tamm, Estonian Air economic benefits of drones. In Estonia unmanned traffic management (UTM) TNavigation Services, UTM Project we are no different and Estonian Air on the same platform, providing shared Manager, explains how digital Navigation Services (EANS) is developing situational awareness for all parties. cloud services will support the growing the concept of operations with (global To push forward with our own plans drone ecosystem: ATM solutions provider) Frequentis for for an Estonian U-space we engaged Drone usage in Estonia is soaring accelerating the roll-out of Estonian Frequentis, who we had worked with on Aerial viewand of theTallinn potential is clear for industry U-space. We have been working on the GOF trials. Frequentis had delivered and infrastructure. But to unleash the this for some time, in various projects, the flight information management possibilities that drones have to offer we including the SESAR Gulf of Finland system (FIMS) for the project, which need a concept to enable them to safely (GOF) U-space project, in 2019, where provides the Common Information share the airspace with manned aviation. we were able to take part in trials for Services (CIS) function and initial Aerial view of Tallinn airport tower, taken during GOF trials 44 ISSUE 2 2021 U-SPACE U-space service provider (USSP) capabilities to the GOF trials. -

Airlines Codes

Airlines codes Sorted by Airlines Sorted by Code Airline Code Airline Code Aces VX Deutsche Bahn AG 2A Action Airlines XQ Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Acvilla Air WZ Denim Air 2D ADA Air ZY Ireland Airways 2E Adria Airways JP Frontier Flying Service 2F Aea International Pte 7X Debonair Airways 2G AER Lingus Limited EI European Airlines 2H Aero Asia International E4 Air Burkina 2J Aero California JR Kitty Hawk Airlines Inc 2K Aero Continente N6 Karlog Air 2L Aero Costa Rica Acori ML Moldavian Airlines 2M Aero Lineas Sosa P4 Haiti Aviation 2N Aero Lloyd Flugreisen YP Air Philippines Corp 2P Aero Service 5R Millenium Air Corp 2Q Aero Services Executive W4 Island Express 2S Aero Zambia Z9 Canada Three Thousand 2T Aerocaribe QA Western Pacific Air 2U Aerocondor Trans Aereos 2B Amtrak 2V Aeroejecutivo SA de CV SX Pacific Midland Airlines 2W Aeroflot Russian SU Helenair Corporation Ltd 2Y Aeroleasing SA FP Changan Airlines 2Z Aeroline Gmbh 7E Mafira Air 3A Aerolineas Argentinas AR Avior 3B Aerolineas Dominicanas YU Corporate Express Airline 3C Aerolineas Internacional N2 Palair Macedonian Air 3D Aerolineas Paraguayas A8 Northwestern Air Lease 3E Aerolineas Santo Domingo EX Air Inuit Ltd 3H Aeromar Airlines VW Air Alliance 3J Aeromexico AM Tatonduk Flying Service 3K Aeromexpress QO Gulfstream International 3M Aeronautica de Cancun RE Air Urga 3N Aeroperlas WL Georgian Airlines 3P Aeroperu PL China Yunnan Airlines 3Q Aeropostal Alas VH Avia Air Nv 3R Aerorepublica P5 Shuswap Air 3S Aerosanta Airlines UJ Turan Air Airline Company 3T Aeroservicios -

االسم Public Warehouse Co. األرز للوكاالت البحرية Volga-Dnepr

اﻻسم Public Warehouse Co. اﻷرز للوكاﻻت البحرية Volga-Dnepr Airlines NEPTUNE Atlantic Airlines NAS AIRLINES RJ EMBASSY FREIGHT JORDAN Phetchabun Airport TAP-AIR PORTUGAL TRANSWEDE AIRWAYS Transbrasil Linhas Aereas TUNIS AIR HAITI TRANS AIR TRANS WORLD AIRLINES,INC ESTONIAN AVIATION SOTIATE NOUVELLE AIR GUADELOUP AMERICAN.TRANS.AIR UNITED AIR LINES MYANMAR AIRWAYS 1NTERNAYIONAL LADECO LINEA AEREA DE1 COBRE. TUNINTER KLM UK LIMITED SRI LANKAN AIRLINES LTD AIR ZIMBABWE CORPORATION TRANSAERO AIRLINE DIRECT AIR BAHAMASAIR U.S.AIR ALLEGHENY AIRLINES FLORIDA GULF AIRLINES PIEDMONT AIRLINES INC P.S.A. AIRLINES USAIR EXPRESS UNION DE TRANSPORTS AERIENS AIR AUSTRAL AIR EUROPA CAMEROON AIRLINES VIASA BIRMINGHAM EXECUTIVE AIRWAYS. SERVIVENS...VENEZUELA AEROVIAS VENEZOLANAS AVENSAS VLM ROYAL.AIR.CAMBODGE REGIONAL AIRLINES VIETNAM AIRLINES TYROLEAN.AIRWAYS VIACAO AEREA SAO PAULO SA.VASP TRANSPORTES.AEREOSDECABO.VERDE VIRGIN ATLANTIC AIRWAYS AIR TAHITI AIR IVOIRE AEROSVIT AIRLINES AIRTOURS.INT,L.GUERNSEY. WESTERN PACIFIC AIRLINES WARDAIR CANADA (1975) LTD. CHALLENGE AIR CARGO INC WIDEROE,S FLYVESELSKAP CHINA NORTHWEST AIRLINES SOUTHWEST AIRLINES WORLD AIRWAYS INC. ALOHA ISLANDAIR WESTERN AIR LINES INC. NIGERIA AIRWAYS LTD AIR.SOUTH CITYJET OMAN AVIATION SERVICES BERLIN EUROPEAN U.K.LTD. CRONUS AIRLINES IATA SINGAPORE LOT GROUND SERVICES LTD. ITR TURBORREACTORES S.A. DE CV IATA MIAMI IATA GENEVE GULF AIRCRAFT MAINTENANCE CO. ACCA C.A.L. CARGO AIRLINES LTD. UNIVERSAL AIR TRAVEL PLAN UATP AIR TRANSPORT ASSOSIATION AUSTRALIAN AIR EXPRESS SITA XS 950 AIR.EXEL.NETHERLANDS PRESIDENTIAL AIRWAYS INC. FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES PTY LTD. CYPRUS.TURKISH.AIRLINES HELI.AIR.MONACO AERO LLOYD LUFTVERKEHRS-AG SKYWEST.AIRLINES MESA AIRLINES INC AIR.NOSTRUM.L.A.M.S.A STATE WEST AIRLINES MIDWEST EXPRESS AIRLINES. -

SAS Group Sustainability Report 2005 English

Welcome aboard SAS Group Annual Report & Sustainability Report 2005 Contents The SAS Group 1 Business areas 27 Financial report 54 Results for the year 2 Scandinavian Airlines Businesses 27 Report by the Board of Directors 54 Important events 3 Scandinavian Airlines Danmark 30 The SAS Group President’s comments 4 SAS Braathens 31 - Statement of income, incl. comments 57 Turnaround 2005 fully implemented 6 Scandinavian Airlines Sverige 32 - Summary statement of income 58 Business concept, vision, objectives & values 7 Scandinavian Airlines International 33 - Balance sheet, incl. comments 59 The SAS Group’s strategies & Operational key figures, ten-year overview 34 - Change in shareholders’ equity 60 management model 8 - Cash flow statement, incl. comments 61 The SAS Group’s brand portfolio 9 Subsidiary & Affiliated Airlines 35 - Accounting and valuation policies 62 New business model & greater Spanair 38 - Notes and supplemental information 65 customer value 10 Widerøe 39 Parent Company SAS AB, statement of income The SAS Group’s markets & growth 12 Blue1 40 and balance sheet, cash flow statement, Analysis of the SAS Group’s competitors 13 airBaltic 41 change in shareholders’ equity and notes 82 Alliances 14 Estonian Air 42 Proposed disposition of earnings 84 Quality, safety & business processes 15 Auditors’ Report 84 Airline Support Businesses 43 SAS Ground Services 44 The capital market SAS Technical Services 45 Corporate governance 85 & Investor Relations 17 SAS Cargo Group 46 Corporate Governance Report 85 Share data 18 - Legal structure -

Airport Punctuality

Punctuality for january 2012 per airline Departures scheduled *) Delayed more than 15 minutes. **) Airlines having less than 10 operations. Avg. Planned Flown Cancelled Flown Delayed *) Punctuality Airline delay (number) (number) (number) (%) (number) (%) (min) Aeroflot Russian 31 31 0 100% 1 97% 21 Airlines Air Baltic 92 92 0 100% 11 88% 24 Air Berlin 81 81 0 100% 3 96% 23 Air Canada 13 13 0 100% 7 46% 47 Air France 131 129 2 98% 17 87% 26 Air Greenland 19 19 0 100% 0 100% 0 Atlantic Airways 71 69 2 97% 10 86% 49 Austrian 105 105 0 100% 7 93% 46 Airlines Blue 1 171 165 6 96% 20 88% 46 British Airways 198 196 2 99% 16 92% 71 British Midland 63 61 2 97% 1 98% 18 Brussels 113 111 2 98% 9 92% 44 Airlines Cimber Sterling 1210 1184 26 98% 136 89% 42 Continental 22 22 0 100% 0 100% 0 Airlines Croatia Airlines 22 21 1 95% 11 50% 52 Csa Czechoslovak 56 56 0 100% 16 71% 34 Airlines Easyjet 265 263 2 99% 22 92% 52 Egypt Air 22 22 0 100% 6 73% 31 Emirates 31 31 0 100% 18 42% 29 Estonian Air 80 79 1 99% 5 94% 70 Finnair 103 103 0 100% 6 94% 46 Flybe 24 23 1 96% 2 92% 31 Flyniki 38 38 0 100% 4 89% 35 Gulf Air 18 18 0 100% 3 83% 24 Iberia 30 29 1 97% 16 47% 53 Iceland Express 18 18 0 100% 3 83% 22 Icelandair 58 58 0 100% 6 90% 110 Jat Airways 18 18 0 100% 8 56% 40 1 Klm Royal Dutch 163 158 5 97% 16 90% 49 Airlines Lot Polskie 60 60 0 100% 12 80% 30 Linie Lotnicze Lufthansa 235 235 0 100% 36 85% 29 Malev Hungarian 53 53 0 100% 16 70% 36 Airlines Meeladair S.A. -

Fly America and Open Skies

Fly America and Open Skies For Travel on Federal Sponsored Awards University and Sponsor Travel Policies • Federal regulations require the customary standard commercial airfare (coach or equivalent), or the lowest commercial discount airfare be charged to a federal sponsored award. • The charging of first‐class air travel is not permitted to a federal sponsored award o except for the traveler’s medical need (must be documented with a medical justification supplied by a primary care provider prior to confirming the reservation). • Frequent flyer miles may be used to upgrade tickets to business class as long as : o The lowest commercial discount airfare was purchased and charged o Note: many airfares purchased at the lowest discounted price are not eligible for upgrades. • http://web.uconn.edu/travel/documents/Travel Policy12‐4‐12.pdf OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT FOR RESEARCH University and Sponsor Travel Policies Fly America – requires the use of a U.S. air carrier even if: o A foreign air carrier service is less expensive, or o A foreign air service is preferred by the traveler, or o A foreign air service is more convenient. Fly America Exceptions: o A U.S. air carrier is not available o When the use of a U.S. carrier service would extend travel time (including delay at origin) by 24 hours or more. o When a U.S. carrier does not offer nonstop or direct service between origin and destination. • Increase the number of aircraft changes outside the United States by two or more • Extend travel time by at least six hours or more • Require a connecting time of four hours or more at an overseas interchange point. -

Thai Airways International Public Company Limited (“THAI”), Ms

THAI AIRWAYS INTERNATIONAL PCL: HEDGING STRATEGIES FOR SMOOTH LANDING Vesarach Aumeboonsuke* Abstract On October 17, 2013, in the aftermath of the 3Q2013 Board Meeting of Thai Airways International Public Company Limited (“THAI”), Ms. Parn (hypothetical name), Financial Risk Manager, was asked by the THAI President, Dr. Sorajak Kasemsuvan, to prepare a financial risk management plan with which to fulfill the commitments that the President had made to the board of directors at the same meeting. The meeting had been a contentious one, with the chairman and board of directors having expressed much dissatisfaction with the report on the Company’s performance and the President’s performance during the first three quarter of the year 2013. They had been insistent in their call for prompt action by the President and management team to improve the airline’s performance. In response to the board meeting, the President had stated that he was going to call for the internal meeting with the management team and discuss strategies to improve the airline’s performance. At the internal meeting, the President and the management team had analyzed that the losses resulted from the high competition in the airlines business, the global economic slowdown, the fuel price fluctuation, and the volatility of foreign currencies that were the sources of income and expenses of THAI. By the end of the meeting, the President and management team had developed the strategies on various aspects to deal with such problems -- for example, to create advertisement and marketing campaign in order to be competitive in the airlines business, to reorganize the airlines routes in order to operate in the profitable environments, and to manage financial risk particularly fuel price risk and foreign exchange rate risk in order to protect the company’s profits from the external factors and maintain financial health of the airline. -

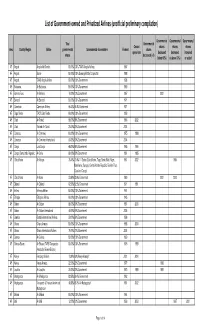

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

When Applying an Exception to the Fly America Act, Documentation (I.E

Travel Policy Fly America Act Compliance Presentation Presented by: Travel Services Agenda • Fly America Act • Exceptions • Open Skies Agreement • Documentation Requirements • Good News and Bad News • CTP demo 3 Travel on Federal Funds Federal regulations require (coach or equivalent), the lowest commercial discount airfare to be charged to a federal sponsored award – No Business Class – No First Class _________________________________________________ Unless a medical exception is noted 4 Fly America Act • Travelers are required by 49 U.S.C. 40118, (Fly America Act), to use U.S. air carrier service for all travel funded by United States Government • Compliance with the Fly America Act is the responsibility of the traveler and department • To ensure compliance with the Fly America Act, travelers are encouraged to use Caltech’s preferred travel agency, CTP or the CardQuest travel portal 5 Fly America Act • Requires the use of a U.S. air carrier for all travel supported by federal funds unless: – A U.S. air carrier is not available – The trip qualifies for an exception as applicable under the Fly America Act 6 Fly America Act Exceptions • Airfare is not funded by U.S. federal funds • Code Share Agreement • Fly America Act Waiver Checklist • No US carrier services a particular leg of route • U.S. carrier involuntarily re-routed traveler • U.S. carrier extends travel time by 6 hours or more hours • Checklist must be submitted with Travel Expense Report (with supporting documentation if necessary) • Open Skies Agreement 7 Fly America Act –Code Share Agreement Compliance with Fly America Act A code share agreement is an arrangement where two or more airlines share the same flight. -

IATA ANNUAL REVIEW 2012 Tony Tyler Director General & CEO

IATA ANNUAL REVIEW 2012 Tony Tyler Director General & CEO International Air Transport Association Annual Report 2012 68th Annual General Meeting Beijing, June 2012 Contents IATA Membership 2 Board of Governors 4 Director General’s message 6 The state of the industry 10 Feature: What is the benefit of global connectivity? Safety 18 Feature: How safe can we be? Security 22 Feature: Do I need to take my shoes off? Taxation & regulatory policy 26 Feature: What is right for the passenger? Environment 30 Feature: Can aviation biofuels work? Simplifying the Business 36 Feature: What’s on offer? Cost efficiency 42 Feature: Why does economic regulation matter? Industry settlement systems 48 Aviation solutions 52 Note: Unless specified otherwise, all dollar ($) figures refer to US dollars (US$). This review uses only 100% recycled paper (Cyclus Print) and vegetable inks. # IATA Membership as of 1 May 2012 ABSA Cargo Airline Air Nostrum Blue Panorama Donavia Adria Airways Air One Blue1 Dragonair Aegean Airlines Air Pacific bmi Dubrovnik Airline Aer Lingus Air Seychelles British Airways Egyptair Aero República Air Tahiti Brussels Airlines EL AL Aeroflot Air Tahiti Nui Bulgaria air Emirates Aerolineas Argentinas Air Transat C.A.L. Cargo Airlines Estonian Air Aeromexico Air Vanuatu Cargojet Airways Ethiopian Airlines Aerosvit Airlines Air Zimbabwe Cargolux Etihad Airways Afriqiyah Airways Aircalin Caribbean Airlines Euroatlantic Airways Aigle Azur Airlink Carpatair European Air Transport Air Algérie Alaska Airlines Cathay Pacific Eurowings Air Astana -

Geoff Dixon, CEO, Qantas Airways James Hogan, President and CEO

A MAGAZINE FOR AIRLINE EXECUTIVES 2004 Issue No. 21 T a k i n g y o u r a i r l i n e t o n e w h e i g h t s ANON ALLIEDTHE ROUTE FRON TOT RECOVE R Y A conversation wAi tconversationh … with … Geoff DixoJamesn, CEO, Qantas AirwaysHogan, President and CEO, Gulf Air INSID E Industry Showing 19 Signs of INSIDRecoveryE Low-CostAir France Carrier and KLM Mode forlm 384 ContinuesEurope’s Largest to Evolv Airline e Recent Breakthroughs 1879 Thein Revenue Evolution Managemen of Alliancets A Conversation with oneworld, SkyTeam 26 and Star Alliance © 2009 Sabre Inc. All rights reserved. [email protected] regional Everything to Gain Estonian Air remained profitable during some of the industry’s lowest points, but the carrier still realizes the need to make major adjustments in order to adapt to a changed marketplace. By Tim Ricketts | Ascend Contributor mid a rapidly transforming This year, the carrier plans to add a fifth air- a profit for the third consecutive year. Estonian industry, the past year also craft to its single fleet of Boeing 737-500s. Air, which earned a net profit of €5.2 million marked a period of great change The airline, owned in part by Scandinavian (US$6.6 million) in 2003, more than doubling for Estonian Air. Airlines (49 percent), the Estonian govern- its €2.5 million (US$3.2 million) net result of the ment (34 percent) and Cresco Ltd., an previous year, carried 410,652 passengers for AIn recent months, the national carrier of the year, a 30 percent increase over the previous the Republic of Estonia added four destina- year, and maintained an average load factor of tions, leased an additional aircraft, introduced Our new and considerably lower 59 percent, five points higher than in 2002.