Dakota Skipper Conservation Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Grasses Benefit Butterflies and Moths Diane M

AFNR HORTICULTURAL SCIENCE Native Grasses Benefit Butterflies and Moths Diane M. Narem and Mary H. Meyer more than three plant families (Bernays & NATIVE GRASSES AND LEPIDOPTERA Graham 1988). Native grasses are low maintenance, drought Studies in agricultural and urban landscapes tolerant plants that provide benefits to the have shown that patches with greater landscape, including minimizing soil erosion richness of native species had higher and increasing organic matter. Native grasses richness and abundance of butterflies (Ries also provide food and shelter for numerous et al. 2001; Collinge et al. 2003) and butterfly species of butterfly and moth larvae. These and moth larvae (Burghardt et al. 2008). caterpillars use the grasses in a variety of ways. Some species feed on them by boring into the stem, mining the inside of a leaf, or IMPORTANCE OF LEPIDOPTERA building a shelter using grass leaves and silk. Lepidoptera are an important part of the ecosystem: They are an important food source for rodents, bats, birds (particularly young birds), spiders and other insects They are pollinators of wild ecosystems. Terms: Lepidoptera - Order of insects that includes moths and butterflies Dakota skipper shelter in prairie dropseed plant literature review – a scholarly paper that IMPORTANT OF NATIVE PLANTS summarizes the current knowledge of a particular topic. Native plant species support more native graminoid – herbaceous plant with a grass-like Lepidoptera species as host and food plants morphology, includes grasses, sedges, and rushes than exotic plant species. This is partially due to the host-specificity of many species richness - the number of different species Lepidoptera that have evolved to feed on represented in an ecological community, certain species, genus, or families of plants. -

Ottoe Skipper (Hesperia Ottoe) in Canada

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Ottoe Skipper (Hesperia ottoe) in Canada Ottoe Skipper ©R. R. Dana 2010 About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)? SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.” What is recovery? In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species’ persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured. What is a recovery strategy? A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage. Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies — Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada — under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/approach/act/default_e.cfm) outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series. -

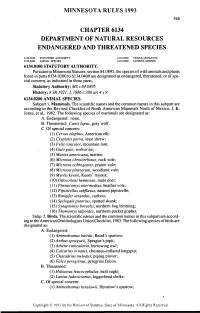

Chapter 6134 Department of Natural Resources Endangered and Threatened Species

MINNESOTA RULES 1993 546 CHAPTER 6134 DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENDANGERED AND THREATENED SPECIES 6134.0100 STATUTORY AUTHORITY. 6134.0300 VASCULAR PLANTS. 6134.0200 ANIMAL SPECIES. 6134.0400 LICHENS; MOSSES. 6134.0100 STATUTORY AUTHORITY. Pursuant to Minnesota Statutes, section 84.0895, the species of wild animals and plants listed in parts 6134.0200 to 6134.0400 are designated as endangered, threatened, or of spe cial concern, as indicated in those parts. Statutory Authority: MS s 84.0895 History: 8SR 1921;L 1986 c386art4s9 6134.0200 ANIMAL SPECIES. Subpart 1. Mammals. The scientific names and the common names in this subpart are according to the Revised Checklist of North American Mammals North of Mexico, J. K. Jones, et al., 1982. The following species of mammals are designated as: A. Endangered: none. B. Threatened: Canis lupus, gray wolf. C. Of special concern: (1) Cervus elaphus, American elk; (2) Cryptotis parva, least shrew; (3) Felis concolor, mountain lion; (4) Gulo gulo, wolverine; (5) Martes americana, marten; (6) Microtus chrotorrhinus, rock vole; (7) Microtus ochrogaster, prairie vole; (8) Microtus pinelorum, woodland vole; (9) Myotis keenii, Keens' myotis; (10) Odocoileus hemionus, mule deer; (11) Phenacomys intermedius, heather vole; (12) Pipistrellus subflavus, eastern pipistrelle; (13) Rangifer tarandus, caribou; (14) Spilogale putorius, spotted skunk; (15) Synaptomys borealis, northern bog lemming; (16) Thomomys talpoides, northern pocket gopher. Subp. 2. Birds. The scientific names and the common names in this subpart are accord ing to the American Ornithologists Union Checklist, 1983. The following species of birds are designated as: A. Endangered: (1) Ammodramus bairdii, Baird's sparrow; (2) Anthus spragueii, Sprague's pipit; (3) Athene cunicularia, burrowing owl; (4) Calcarius ornatus, chestnut-collared longspur; (5) Charadrius melodus, piping plover; (6) Falco peregrinus, peregrine falcon. -

Recovery Strategy for the Dakota Skipper (Hesperia Dacotae) in Canada

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae) in Canada Dakota Skipper 2007 About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)? SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.” What is recovery? In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species’ persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured. What is a recovery strategy? A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage. Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies — Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada — under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/the_act/default_e.cfm) outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series. -

The Status of Dakota Skipper (Hesperia Dacotae Skinner) in Eastern South Dakota and the Effects of Land Management

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020 The Status of Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae Skinner) in Eastern South Dakota and the Effects of Land Management Kendal Annette Davis South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Kendal Annette, "The Status of Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae Skinner) in Eastern South Dakota and the Effects of Land Management" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3914. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/3914 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STATUS OF DAKOTA SKIPPER (HESPERIA DACOTAE SKINNER) IN EASTERN SOUTH DAKOTA AND THE EFFECTS OF LAND MANAGEMENT BY KENDAL ANNETTE DAVIS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Major in Plant Sciences South Dakota State University 2020 ii THESIS ACCEPTANCE PAGE KENDAL ANNETTE DAVIS This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investigation by a candidate for the master’s degree and is acceptable for meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this does not imply that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. Paul Johnson Advisor Date David Wright Department Head Date Dean, Graduate School Date iii AKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank my advisor, Dr. -

Common Kansas Butterflies ■ ■ ■ ■ ■

A POCKET GUIDE TO Common Kansas Butterflies ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ By Jim Mason Funded by Westar Energy Green Team, Glenn Springs Holdings, Inc., Occidental Chemical Corporation and the Chickadee Checkoff Published by the Friends of the Great Plains Nature Center Table of Contents • Introduction • 2 • Butterflies vs. Moths • 4 • Observing Butterflies • 4 Family Papilionidae - Swallowtails ■ Pipevine Swallowtail • 6 ■ Zebra Swallowtail • 7 ■ Black Swallowtail • 8 ■ Giant Swallowtail • 9 ■ Eastern Tiger Swallowtail • 10 Family Pieridae – Whites & Sulphurs ■ Checkered White • 11 ■ Cabbage White • 12 ■ Clouded Sulphur • 13 ■ Orange Sulphur • 14 ■ Cloudless Sulphur • 15 ■ Sleepy Orange • 16 ■ Little Yellow • 17 ■ Dainty Sulphur • 18 ■ Southern Dogface • 19 Family Lycaenidae – Gossamer-Wings ■ Gray Copper • 20 ■ Bronze Copper • 21 ■ Coral Hairstreak • 22 ■ Gray Hairstreak • 23 ■ Juniper Hairstreak • 24 ■ Reakirts' Blue • 25 ■ Eastern Tailed-Blue • 26 ■ Spring Azure and Summer Azure • 27 Family Nymphalidae – Brushfoots ■ American Snout • 28 ■ Variegated Fritillary • 29 ■ Great Spangled Fritillary • 30 ■ Regal Fritillary • 31 ■ Gorgone Checkerspot • 32 ■ Silvery Checkerspot • 33 ■ Phaon Crescent • 34 ■ Pearl Crescent • 35 ■ Question Mark • 36 ■ Eastern Comma • 37 ■ Mourning Cloak • 38 ■ American Lady • 39 ©Greg Sievert ■ Painted Lady • 40 ■ Red Admiral • 41 ■ Common Buckeye • 42 ■ Red-spotted Purple • 43 ■ Viceroy • 44 ■ Goatweed Leafwing • 45 ■ Hackberry Emperor • 46 ■ Tawny Emperor • 47 ■ Little Wood Satyr • 48 ■ Common Wood Nymph • 49 ■ Monarch • 50 Family -

Ottoe Skipper (Hesperia Ottoe)

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Ottoe Skipper Hesperia ottoe in Canada ENDANGERED 2005 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2005. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Ottoe Skipper Hesperia ottoe in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 26 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Dr. Reginald P. Webster for writing the status report on the Ottoe Skipper Hesperia ottoe prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Theresa Fowler, the COSEWIC Arthropods Species Specialist Subcommittee Co-chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Ếgalement disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur de l'hespérie ottoé (Hesperia ottoe) au Canada. Cover illustration: Ottoe skipper — Male (top) and female (bottom) of Hesperia ottoe. Photos provided by the author. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2005 Catalogue No. CW69-14/448-2005E-PDF ISBN 0-662-40660-5 HTML: CW69-14/448-2005E-HTML 0-662-40661-3 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – May 2005 Common name Ottoe Skipper Scientific name Hesperia ottoe Status Endangered Reason for designation This species has been found at very few locations in the Canadian prairies where it is associated with fragmented and declining mixed-grass prairie vegetation. -

Butterflies (Lepidoptera) on Hill Prairies of Allamakee County, Iowa: a Comparison of the Late 1980S with 2013 Nicole M

114 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST Vol. 47, Nos. 3 - 4 Butterflies (Lepidoptera) on Hill Prairies of Allamakee County, Iowa: A Comparison of the Late 1980s With 2013 Nicole M. Powers1 and Kirk J. Larsen1* Abstract In the late 1980s, several hundred butterflies were collected by John Nehnevaj from hill prairies and a fen in Allamakee County, Iowa. Nehnevaj’s collection included 69 species, 14 of which are currently listed in Iowa as species of greatest conservation need (SGCN). The goal of this study was to revisit sites surveyed in the 1980s and survey three additional sites to compare the species present in 2013 to the species found by Nehnevaj. A primary objective was to document the presence of rare prairie specialist butterflies (Lepidoptera), specifi- cally the ottoe skipper (Hesperia ottoe W.H. Edwards; Hesperiidae), which was thought to be extirpated from Iowa. Twelve sites were surveyed 4 to 7 times between June and September 2013 using a meandering Pollard walk technique. A total of 2,860 butterflies representing 58 species were found; eight of these species were SGCN’s, including the hickory hairstreak (Satyrium caryaevorum McDunnough; Lycaenidae), and Leonard's skipper (Hesperia leonardus Harris; Hesperiidae), species not collected in the 1980s, and the ottoe skipper and Balti- more checkerspot (Euphydryas phaeton Drury; Nymphalidae), both species also found by Nehnevaj. Species richness for the sites ranged from 14 to 33 species, with SGCNs found at 11 of the 12 sites. Significant landscape changes have occurred to hill prairies in Allamakee County over the past 25 years. Invasion by red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) has reduced hill prairie an average of 55.4% at these sites since the 1980s, but up to 100% on some of the sites surveyed by Nehnevaj. -

Implementation Guide to the DRAFT

2015 Implementation Guide to the DRAFT As Prescribed by The Wildlife Conservation and Restoration Program and the State Wildlife Grant Program Illinois Wildlife Action Plan 2015 Implementation Guide Table of Contents I. Acknowledgments IG 1 II. Foreword IG 2 III. Introduction IG 3 IV. Species in Greatest Conservation Need SGCN 8 a. Table 1. SummaryDRAFT of Illinois’ SGCN by taxonomic group SGCN 10 V. Conservation Opportunity Areas a. Description COA 11 b. What are Conservation Opportunity Areas COA 11 c. Status as of 2015 COA 12 d. Ways to accomplish work COA 13 e. Table 2. Summary of the 2015 status of individual COAs COA 16 f. Table 3. Importance of conditions for planning and implementation COA 17 g. Table 4. Satisfaction of conditions for planning and implementation COA 18 h. Figure 1. COAs currently recognized through Illinois Wildlife Action Plan COA 19 i. Figure 2. Factors that contribute or reduce success of management COA 20 j. Figure 3. Intersection of COAs with Campaign focus areas COA 21 k. References COA 22 VI. Campaign Sections Campaign 23 a. Farmland and Prairie i. Description F&P 23 ii. Goals and Current Status as of 2015 F&P 23 iii. Stresses and Threats to Wildlife and Habitat F&P 27 iv. Focal Species F&P 30 v. Actions F&P 32 vi. Focus Areas F&P 38 vii. Management Resources F&P 40 viii. Performance Measures F&P 42 ix. References F&P 43 x. Table 5. Breeding Bird Survey Data F&P 45 xi. Figure 4. Amendment to Mason Co. Sands COA F&P 46 xii. -

(Skinner) (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) Iowa, Minneso

STATUS ASSESSMENT and CONSERVATION GUIDELINES Dakota Skipper Hesperia dacotae (Skinner) (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) Iowa, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Manitoba Jean Fitts Cochrane and Philip Delphey • U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Twin Cities Field Office January 2002 Disclaimer This document is a compilation of biological data and a description of past, present, and likely future threats to the Dakota skipper (Hesperia dacotae). It does not represent a decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) on whether this species should be designated as a candidate for listing as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will make that decision after reviewing this document, other relevant biological and threat data not including herein, and all relevant laws, regulations, and policies. The results of the decision will be posted on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Region 3 Web site, http://www.fws.gov/r3pao/eco_serv/endangrd/lists/concem.html. If designated as a candidate species, it will subsequently be added to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's candidate species list that is periodically published in the Federal Register and posted on the World Wide Web, http ://endangered.fws. gov/. Even if the species does not warrant candidate status it should benefit from the conservation recommendations contained in this document. — • n TABLE OF CONTENTS Part One: Status Assessment 1 I. Introduction 1 II. Species Information 1 A. Classification and Nomenclature 1 B. Description of the Species 2 C. Summary of Habitat, Biology, and Ecology 3 D. Range and Population Trends 11 EL Population Assessment ."....".....21 A. -

The Status of Iowa's Lepidoptera

Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS Volume 105 Number Article 9 1998 The Status of Iowa's Lepidoptera Dennis W. Schlicht Timothy T. Orwig Morningside College Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright © Copyright 1998 by the Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias Part of the Anthropology Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Schlicht, Dennis W. and Orwig, Timothy T. (1998) "The Status of Iowa's Lepidoptera," Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS, 105(2), 82-88. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/jias/vol105/iss2/9 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the Iowa Academy of Science: JIAS by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jour. Iowa Acad. Sci. 105(2):82-88, 1998 The Status of Iowa's Lepidoptera DENNIS W. SCHLICHT1 and TIMOTHY T. ORWIG2 1 Iowa Lepidoptera Project, 1108 First Avenue, Center Point, Iowa 52213. 2 Morningside College, Sioux City, Iowa 51106. Including strays, 122 species of butterflies have been confirmed in Iowa. However, since European settlement the populations of taxa of Iowa Lepidoptera have declined. While certain generalist species have experienced declines, species with life cycles that include native habitats, especially prairies and wetlands, have been particularly vulnerable. In a 1994 revision of the Iowa endangered and threatened species list, the Natural Resource Commission (NRC) listed two species of butterflies as endangered, five as threatened, and 25 as special concern, using general legal definitions of those rankings (NRC 1994). -

Wisconsin Entomoloqical Society Newsletter

Wisconsin Entomoloqical Society Newsletter Volume 43, Number 1 February 2016 Welcome Dr. Craig Brabant, Academic Curator, UW Insect Research Collection By Daniel K. Young, Ph.D. [email protected] Please join me in welcoming Dr. Craig Brabant, 4th Academic Curator of the University of Wisconsin Insect Research Collection (WIRC), following the long career of Distinguished Curator, Steven During the last four years of his Krauth. Craig will be already well known to degree program, Dr. Brabant was a Research some of you as a former student in my Assistant under an NSF grant I shared with a Systematic Entomology Laboratory where number of other insect collections. This he completed a Master's thesis conducting a grant, attached to the WIRC under my survey of the velvet ants (Hymenoptera: directorship, is entitled "Advancing Mutillidae) if Wisconsin in 2003. With a Digitization of Biodiversity Collections" passion to continue his studies on (ADBC) - part of the InvertNet group Mutillidae, Craig embarked on a doctoral (http://invertnet.org/about). This work research project entitled, required hands-on, day-to-day work in the "Taxonomic Revision and Phylogenetic collection and daily demonstration of a Analysis of the South American robust suite of curatorial skills from Genus Tallium Andre (Hymenoptera: specimen interpolation of incoming new Mutillidae)." Craig defended his dissertation material and handling loan transactions to this past August. taxonomically revising and phylogenetically updating large portions of the collection holdings; from assisting with planning and Our collection website has largely been his carrying out a major move and expansion of product (ht_m_://lab~russell. wisc.edu/~irc/) the collection holdings into our expansion conceptually, in terms of layout, and now facility in the Stock Pavilion, the "WIRC content.