Declines of Prairie Butterflies in the Midwestern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pollinator Butterfly Habitat

The ecology and conservation of grassland butterflies in the central U.S. Dr. Ray Moranz Moranz Biological Consulting 4514 North Davis Court Stillwater, Oklahoma 74075 Outline of the Presentation, Part I • Basic butterfly biology • Butterflies as pollinators • Rare butterflies of Kansas Outline of the Presentation, Part 2 • Effects of fire and grazing on grassland butterflies • Resources to learn more about butterflies • 15 common KS butterflies Life Cycle of a Painted Lady, Vanessa cardui Egg Larva Adult Chrysalis Some butterflies migrate The Monarch is the best-known migratory butterfly Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, North Dakota Fall migratory pathways of the Monarch The Painted Lady is another migrant Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico Other butterflies are non- migratory Such as this regal fritillary, seen in Anderson County, Kansas Implications of migratory status -migratory butterflies aren’t vulnerable to prescribed burns in winter and early spring (they haven’t arrived yet) -full-year resident butterflies ARE vulnerable to winter and spring fires -migratory butterflies may need lots of nectar sources on their flyway to fuel their flight Most butterfly caterpillars are host plant specialists Implications of host plant specialization • If you have the host plant, you probably have the butterfly • If you plant their host, the butterfly may follow • If you and your neighbors lack the host plants, you are unlikely to see the butterflies except during migration Butterflies as pollinators • Bees pollinate more plant -

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations Revised Report and Documentation Prepared for: Department of Defense U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Submitted by: January 2004 Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations: Revised Report and Documentation CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary..........................................................................................iii 2.0 Introduction – Project Description................................................................. 1 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NatureServe Data................................................................................................ 3 3.2 DOD Installations............................................................................................... 5 3.3 Species at Risk .................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Results................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Nationwide Assessment of Species at Risk on DOD Installations..................... 8 4.2 Assessment of Species at Risk by Military Service.......................................... 13 4.3 Assessment of Species at Risk on Installations ................................................ 15 5.0 Conclusion and Management Recommendations.................................... 22 6.0 Future Directions............................................................................................. -

Conservation of the Arogos Skipper, Atrytone Arogos Arogos (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) in Florida Marc C

Conservation of the Arogos Skipper, Atrytone arogos arogos (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) in Florida Marc C. Minno St. Johns River Water Management District P.O. Box 1429, Palatka, FL 32177 [email protected] Maria Minno Eco-Cognizant, Inc., 600 NW 35th Terrace, Gainesville, FL 32607 [email protected] ABSTRACT The Arogos skipper is a rare and declining butterfly found in native grassland habitats in the eastern and mid- western United States. Five distinct populations of the butterfly occur in specific parts of the range. Atrytone arogos arogos once occurred from southern South Carolina through eastern Georgia and peninsular Florida as far south as Miami. This butterfly is currently thought to be extirpated from South Carolina and Georgia. The six known sites in Florida for A. arogos arogos are public lands with dry prairie or longleaf pine savanna having an abundance of the larval host grass, Sorghastrum secundum. Colonies of the butterfly are threat- ened by catastrophic events such as wild fires, land management activities or no management, and the loss of genetic integrity. The dry prairie preserves of central Florida will be especially important to the recovery of the butterfly, since these are some of the largest and last remaining grasslands in the state. It may be possible to create new colonies of the Arogos skipper by releasing wild-caught females or captive-bred individuals into currently unoccupied areas of high quality habitat. INTRODUCTION tered colonies were found in New Jersey, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, and Mississippi. The three re- gions where the butterfly was most abundant included The Arogos skipper (Atrytone arogos) is a very locally the New Jersey pine barrens, peninsular Florida, and distributed butterfly that occurs only in the eastern and southeastern Mississippi. -

Minutes from the Poweshiek Skipperling Workshop

2011 Minutes from the Poweshiek Skipperling Workshop Photo: J. Dupont Winnipeg, Manitoba March 24th and 25th The minutes below represent the collective views captured and opinions of the experts who gathered to discuss the Poweshiek Skipperling. The views expressed in this document don’t represent the views of any one participant. The Workshop was led by the Nature Conservancy of Canada, Manitoba Region, and the minutes were summarized from audio recording and written notes by Jaimée Dupont. We would like to extend huge thank you to all of the individuals and organizations that attended and contributed to the workshop. We would also like to thank our sponsors: Abstract The objectives of this workshop were to bring together the Poweshiek Skipperling experts and those responsible for managing the species’ habitat from across its range, and open the lines of communication between them. Key goals of this workshop included identifying common trends amongst populations, discussing potential causes of these trends, identifying key research gaps and discussing how to fill these gaps. Workshop discussions provided immediate feedback and direction for National Recovery Planning and Implementation efforts that are currently underway in Canada and the USA. Conservation actions that should occur (range-wide and locally) were identified to ensure ongoing persistence of the species. The dramatic and seemingly concurrent declines seen locally were, unfortunately, echoed by participants from across the range (with the exception of Michigan). Workshop participants identified several potential causes of the species’ range- wide decline. Several potential factors that may be operating on a range-wide scale were discussed, and several lines of investigation were identified as critical research needs. -

Native Grasses Benefit Butterflies and Moths Diane M

AFNR HORTICULTURAL SCIENCE Native Grasses Benefit Butterflies and Moths Diane M. Narem and Mary H. Meyer more than three plant families (Bernays & NATIVE GRASSES AND LEPIDOPTERA Graham 1988). Native grasses are low maintenance, drought Studies in agricultural and urban landscapes tolerant plants that provide benefits to the have shown that patches with greater landscape, including minimizing soil erosion richness of native species had higher and increasing organic matter. Native grasses richness and abundance of butterflies (Ries also provide food and shelter for numerous et al. 2001; Collinge et al. 2003) and butterfly species of butterfly and moth larvae. These and moth larvae (Burghardt et al. 2008). caterpillars use the grasses in a variety of ways. Some species feed on them by boring into the stem, mining the inside of a leaf, or IMPORTANCE OF LEPIDOPTERA building a shelter using grass leaves and silk. Lepidoptera are an important part of the ecosystem: They are an important food source for rodents, bats, birds (particularly young birds), spiders and other insects They are pollinators of wild ecosystems. Terms: Lepidoptera - Order of insects that includes moths and butterflies Dakota skipper shelter in prairie dropseed plant literature review – a scholarly paper that IMPORTANT OF NATIVE PLANTS summarizes the current knowledge of a particular topic. Native plant species support more native graminoid – herbaceous plant with a grass-like Lepidoptera species as host and food plants morphology, includes grasses, sedges, and rushes than exotic plant species. This is partially due to the host-specificity of many species richness - the number of different species Lepidoptera that have evolved to feed on represented in an ecological community, certain species, genus, or families of plants. -

Ottoe Skipper (Hesperia Ottoe) in Canada

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Ottoe Skipper (Hesperia ottoe) in Canada Ottoe Skipper ©R. R. Dana 2010 About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)? SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.” What is recovery? In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species’ persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured. What is a recovery strategy? A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage. Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies — Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada — under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/approach/act/default_e.cfm) outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series. -

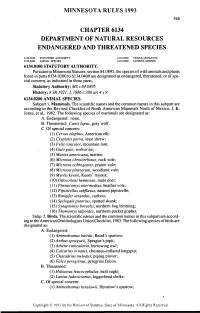

Chapter 6134 Department of Natural Resources Endangered and Threatened Species

MINNESOTA RULES 1993 546 CHAPTER 6134 DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENDANGERED AND THREATENED SPECIES 6134.0100 STATUTORY AUTHORITY. 6134.0300 VASCULAR PLANTS. 6134.0200 ANIMAL SPECIES. 6134.0400 LICHENS; MOSSES. 6134.0100 STATUTORY AUTHORITY. Pursuant to Minnesota Statutes, section 84.0895, the species of wild animals and plants listed in parts 6134.0200 to 6134.0400 are designated as endangered, threatened, or of spe cial concern, as indicated in those parts. Statutory Authority: MS s 84.0895 History: 8SR 1921;L 1986 c386art4s9 6134.0200 ANIMAL SPECIES. Subpart 1. Mammals. The scientific names and the common names in this subpart are according to the Revised Checklist of North American Mammals North of Mexico, J. K. Jones, et al., 1982. The following species of mammals are designated as: A. Endangered: none. B. Threatened: Canis lupus, gray wolf. C. Of special concern: (1) Cervus elaphus, American elk; (2) Cryptotis parva, least shrew; (3) Felis concolor, mountain lion; (4) Gulo gulo, wolverine; (5) Martes americana, marten; (6) Microtus chrotorrhinus, rock vole; (7) Microtus ochrogaster, prairie vole; (8) Microtus pinelorum, woodland vole; (9) Myotis keenii, Keens' myotis; (10) Odocoileus hemionus, mule deer; (11) Phenacomys intermedius, heather vole; (12) Pipistrellus subflavus, eastern pipistrelle; (13) Rangifer tarandus, caribou; (14) Spilogale putorius, spotted skunk; (15) Synaptomys borealis, northern bog lemming; (16) Thomomys talpoides, northern pocket gopher. Subp. 2. Birds. The scientific names and the common names in this subpart are accord ing to the American Ornithologists Union Checklist, 1983. The following species of birds are designated as: A. Endangered: (1) Ammodramus bairdii, Baird's sparrow; (2) Anthus spragueii, Sprague's pipit; (3) Athene cunicularia, burrowing owl; (4) Calcarius ornatus, chestnut-collared longspur; (5) Charadrius melodus, piping plover; (6) Falco peregrinus, peregrine falcon. -

Recovery Strategy for the Dakota Skipper (Hesperia Dacotae) in Canada

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae) in Canada Dakota Skipper 2007 About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)? SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.” What is recovery? In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species’ persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured. What is a recovery strategy? A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage. Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies — Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada — under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/the_act/default_e.cfm) outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series. -

Integrating the Conservation of Plant Species of Concern in the New Jersey State Wildlife Action Plan

Integrating the Conservation of Plant Species of Concern in the New Jersey State Wildlife Action Plan Prepared by Kathleen Strakosch Walz New Jersey Natural Heritage Program New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection State Forestry Services Office of Natural Lands Management 501 East State Street, 4th Floor MC501-04, PO Box 420 Trenton, NJ 08625-0420 For NatureServe 4600 N. Fairfax Drive – 7th Floor Arlington, VA 22203 Project #DDF-0F-001a Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (Plants) June 2013 NatureServe # DDCF-0F-001a Integration of Plants into NJ SWAP Page | 1 Suggested citation: Walz, Kathleen S. 2013. Integrating the Conservation of Plant Species of Concern in the New Jersey State Wildlife Action Plan. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Office of Natural Lands Management, MC501-04, Trenton, NJ 08625 for NatureServe #DDCF-0F-001a, 12p. Cover Photographs: Top Row: Spreading globeflower (Trollius laxus spp. Laxus) in calcareous fen habitat; Appalachian Mountain boltonia ( Boltonia montana) in calcareous sinkhole pond habitat of the Skylands Landscape Regional Landscape (photographs by Kathleen Strakosch Walz) Bottom Row: Bog asphodel (Narthecium americanum) in Pine Barren riverside savanna habitat; Reversed bladderwort (Utricularia resupinata) in coastal plain intermittent pond habitat of the Pinelands Regional Landscape (photographs by Renee Brecht) NatureServe # DDCF-0F-001a Integration of Plants into NJ SWAP Page | 2 PROJECT SUMMARY Overall purpose/intent: New Jersey is the first state projected to reach build-out, and pressure from competing land use interests and associated threats is high on the remaining open space. Therefore it is imperative to strategically protect and manage these natural areas for resiliency, as it is on these lands where the future of conservation lies for plants, animals and their critical habitats. -

2012 Edmonton, Alberta

October 2013 ISSN 0071-0709 PROCEEDINGS OF THE 60TH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE Entomological Society of Alberta November 4th-7th 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Entomological Society of Alberta Board of Directors 2012 ....................................... 5 Annual Meeting Committees 2012 ..................................................................................... 5 Program of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of Alberta .... 6 Oral Presentations ................................................................................................................ 12 Poster Presentations ............................................................................................................ 26 Index to Authors..................................................................................................................... 29 Minutes of the Entomological Society of Alberta Executive Meeting .................. 40 DRAFT Minutes of the Entomological Society of Alberta 60th Annual AGM ...... 42 Regional Director’s Report ................................................................................................. 45 Northern Director’s Report ................................................................................................ 47 Central Director’s Report .................................................................................................... 51 Southern Director’s Report ................................................................................................ 53 Webmaster’s Report ............................................................................................................ -

Arogos Skipper (Atrytone Arogos)

REGION 2 SENSITIVE SPECIES EVALUATION FORM Species: Arogos skipper (Atrytone arogos) Criteria Rank Rationale Literature Citations The Arogos skipper is a transient migrant in Wyoming, South Dakota, and Nebraska • www.natureserve.org 1 A and breeds in Colorado and Kansas. Distribution within R2 Confidence in Rank High or Medium or Low The Arogos skipper occurs from Long Island south along the piedmont (in New Jersey • www.natureserve.org 2 C and formerly Pennsylvania only) and coastal plain in a very few isolated colonies to Distribution • citations in references outside R2 peninsular Florida and west along the Gulf to eastern Louisiana. A separate group of populations (subspecies IOWA) occurs on the prairies from southern Minnesota and section adjacent Wisconsin west to eastern Wyoming and south to Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, and northeastern Colorado (Opler and Krizek, 1984). Subspecies IOWA east in isolated colonies to western Arkansas and western Illinois. Very patchy range (Royer and Marrone, 1992) even in the prairie region. Confidence in Rank High or Medium or Low The species is a metapopulation species associated with remnant natural grasslands • citations in references 3 D or savannas eastward (Schweitzer, 2000; Hall, 1999) and unlikely to persist as Dispersal section Capability isolated colonies there. Lack of functioning metapopulation structure may doom some "protected" prairie populations especially with frequent fires superimposed on the fragments. Species may be unable to find isolated patches of prairie. Confidence in Rank High or Medium or Low Local and usually uncommon from New Jersey to Florida, westward to Texas, eastern • www.natureserve.org 4 D Colorado, Wyoming and the Black Hills (Ferris 1981). -

The Status of Dakota Skipper (Hesperia Dacotae Skinner) in Eastern South Dakota and the Effects of Land Management

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020 The Status of Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae Skinner) in Eastern South Dakota and the Effects of Land Management Kendal Annette Davis South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Kendal Annette, "The Status of Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae Skinner) in Eastern South Dakota and the Effects of Land Management" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3914. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/3914 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STATUS OF DAKOTA SKIPPER (HESPERIA DACOTAE SKINNER) IN EASTERN SOUTH DAKOTA AND THE EFFECTS OF LAND MANAGEMENT BY KENDAL ANNETTE DAVIS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Major in Plant Sciences South Dakota State University 2020 ii THESIS ACCEPTANCE PAGE KENDAL ANNETTE DAVIS This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investigation by a candidate for the master’s degree and is acceptable for meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this does not imply that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. Paul Johnson Advisor Date David Wright Department Head Date Dean, Graduate School Date iii AKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I want to thank my advisor, Dr.