(Skinner) (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) Iowa, Minneso

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV Maps and Descriptions Denis White March 2020

Ecological Regions of Minnesota: Level III and IV maps and descriptions Denis White March 2020 (Image NOAA, Landsat, Copernicus; Presentation Google Earth) A contribution to the corpus of materials created by James Omernik and colleagues on the Ecological Regions of the United States, North America, and South America The page size for this document is 9 inches horizontal by 12 inches vertical. Table of Contents Content Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Geographic patterns in Minnesota 1 Geographic location and notable features 1 Climate 1 Elevation and topographic form, and physiography 2 Geology 2 Soils 3 Presettlement vegetation 3 Land use and land cover 4 Lakes, rivers, and watersheds; water quality 4 Flora and fauna 4 3. Methods of geographic regionalization 5 4. Development of Level IV ecoregions 6 5. Descriptions of Level III and Level IV ecoregions 7 46. Northern Glaciated Plains 8 46e. Tewaukon/BigStone Stagnation Moraine 8 46k. Prairie Coteau 8 46l. Prairie Coteau Escarpment 8 46m. Big Sioux Basin 8 46o. Minnesota River Prairie 9 47. Western Corn Belt Plains 9 47a. Loess Prairies 9 47b. Des Moines Lobe 9 47c. Eastern Iowa and Minnesota Drift Plains 9 47g. Lower St. Croix and Vermillion Valleys 10 48. Lake Agassiz Plain 10 48a. Glacial Lake Agassiz Basin 10 48b. Beach Ridges and Sand Deltas 10 48d. Lake Agassiz Plains 10 49. Northern Minnesota Wetlands 11 49a. Peatlands 11 49b. Forested Lake Plains 11 50. Northern Lakes and Forests 11 50a. Lake Superior Clay Plain 12 50b. Minnesota/Wisconsin Upland Till Plain 12 50m. Mesabi Range 12 50n. Boundary Lakes and Hills 12 50o. -

Pollinator Butterfly Habitat

The ecology and conservation of grassland butterflies in the central U.S. Dr. Ray Moranz Moranz Biological Consulting 4514 North Davis Court Stillwater, Oklahoma 74075 Outline of the Presentation, Part I • Basic butterfly biology • Butterflies as pollinators • Rare butterflies of Kansas Outline of the Presentation, Part 2 • Effects of fire and grazing on grassland butterflies • Resources to learn more about butterflies • 15 common KS butterflies Life Cycle of a Painted Lady, Vanessa cardui Egg Larva Adult Chrysalis Some butterflies migrate The Monarch is the best-known migratory butterfly Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, North Dakota Fall migratory pathways of the Monarch The Painted Lady is another migrant Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico Other butterflies are non- migratory Such as this regal fritillary, seen in Anderson County, Kansas Implications of migratory status -migratory butterflies aren’t vulnerable to prescribed burns in winter and early spring (they haven’t arrived yet) -full-year resident butterflies ARE vulnerable to winter and spring fires -migratory butterflies may need lots of nectar sources on their flyway to fuel their flight Most butterfly caterpillars are host plant specialists Implications of host plant specialization • If you have the host plant, you probably have the butterfly • If you plant their host, the butterfly may follow • If you and your neighbors lack the host plants, you are unlikely to see the butterflies except during migration Butterflies as pollinators • Bees pollinate more plant -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Chapter 85

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 85.011 CHAPTER 85 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION STATE PARKS, RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES 85.06 SCHOOLHOUSES IN CERTAIN STATE PARKS. 85.011 CONFIRMATION OF CREATION AND 85.20 VIOLATIONS OF RULES; LITTERING; PENALTIES. ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE PARKS, STATE 85.205 RECEPTACLES FOR RECYCLING. RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES. 85.21 STATE OPERATION OF PARK, MONUMENT, 85.0115 NOTICE OF ADDITIONS AND DELETIONS. RECREATION AREA AND WAYSIDE FACILITIES; 85.012 STATE PARKS. LICENSE NOT REQUIRED. 85.013 STATE RECREATION AREAS AND WAYSIDES. 85.22 STATE PARKS WORKING CAPITAL ACCOUNT. 85.014 PRIOR LAWS NOT ALTERED; REVISOR'S DUTIES. 85.23 COOPERATIVE LEASES OF AGRICULTURAL 85.0145 ACQUIRING LAND FOR FACILITIES. LANDS. 85.0146 CUYUNA COUNTRY STATE RECREATION AREA; 85.32 STATE WATER TRAILS. CITIZENS ADVISORY COUNCIL. 85.33 ST. CROIX WILD RIVER AREA; LIMITATIONS ON STATE TRAILS POWER BOATING. 85.015 STATE TRAILS. 85.34 FORT SNELLING LEASE. 85.0155 LAKE SUPERIOR WATER TRAIL. TRAIL PASSES 85.0156 MISSISSIPPI WHITEWATER TRAIL. 85.40 DEFINITIONS. 85.016 BICYCLE TRAIL PROGRAM. 85.41 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI PASSES. 85.017 TRAIL REGISTRY. 85.42 USER FEE; VALIDITY. 85.018 TRAIL USE; VEHICLES REGULATED, RESTRICTED. 85.43 DISPOSITION OF RECEIPTS; PURPOSE. ADMINISTRATION 85.44 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI TRAIL GRANT-IN-AID 85.019 LOCAL RECREATION GRANTS. PROGRAM. 85.021 ACQUIRING LAND; MINNESOTA VALLEY TRAIL. 85.45 PENALTIES. 85.04 ENFORCEMENT DIVISION EMPLOYEES. 85.46 HORSE -

To Prairie Preserves

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp (Funding for document digitization was provided, in part, by a grant from the Minnesota Historical & Cultural Heritage Program.) A GUIDE TO MINNESOTA PRAIRIES By Keith M. Wendt Maps By Judith M. Ja.cobi· Editorial Assistance By Karen A. Schmitz Art and Photo Credits:•Thorn_as ·Arter, p. 14 (bottom left); Kathy Bolin, ·p: 14 (top); Dan Metz, pp. 60, 62; Minnesota Departme'nt of Natural Resources, pp. '35 1 39, 65; U.S. Department of Agriculture, p. -47; Keith Wendt, cover, pp~ 14 (right), 32, 44; Vera Wohg, PP· 22, 43, 4a. · · ..·.' The Natural Heritage Program Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Box 6, Centennial Office Building . ,. St. Paul; MN 55155 ©Copyright 1984, State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resource.s CONTENTS PREFACE .......................................... Page 3 INTRODUCTION .................................... Page 5 MINNESOTA PRAIRIE TYPES ........................... Page 6 PROTECTION STATUS OF MINNESOTA PRAIRIES ............ Page 12 DIRECTORY OF PRAIRIE PRESERVES BY REGION ............ Page 15 Blufflands . Page 18 Southern Oak Barrens . Page 22 Minnesota River Valley ............................. Page 26 Coteau des Prairies . Page 32 Blue Hills . Page 40 Mississippi River Sand Plains ......................... Page 44 Red River Valley . Page 48 Aspen Parkland ................................... Page 62 REFERENCES ..................................... Page 66 INDEX TO PRAIRIE PRESERVES ......................... Page 70 2 PREFACE innesota has established an outstanding system of tallgrass prairie preserves. No state M in the Upper Midwest surpasses Minnesota in terms of acreage and variety of tallgrass prairie protected. Over 45,000 acres of native prairie are protected on a wide variety of landforms that span the 400 mile length of the state from its southeast to northwest corner. -

Explore Minnesota S Prairies

Explore Minnesota s Prairies A guide to selected prairies around the state. By Peter Buesseler ECAUSE I'M the Depart- ment of Natural Re- sources state prairie biologist, people of- Bten ask me where they can go to see a prairie. Fortunately, Minnesota has established an outstanding system of prai- rie preserves. No state in the upper Midwest surpasses Minnesota in terms of acre- age and variety of tallgrass prairie protected. There is Among the prairies to explore are spectacular probably native prairie closer bluffland prairies located just a few hours south to you than you think. of the Twin Cities along the Mississippi River. When is the best time to visit a prairie? From the first pasque Read about the different prairie flowers and booming of prairie chick- regions and preserves described be- ens in April, to the last asters and low, then plan an outing with family bottle gentians in October, the prairie or friends. The most important thing is a kaleidoscope of color and change. is not when or where to go—just go! So don't worry. Every day is a good The following abbreviations are day to see prairie. used in the list of prairie sites: SNA 30 THE MINNESOTA VOLUNTEER means the prairie is a state scientific wildlife refuge. My personal favorites and natural area; TNC means the are marked with an asterisk (*). Have prairie is owned by The Nature Con- fun exploring your prairie heritage. servancy, a private, nonprofit conser- Red River Valley vation organization; WMA means the During the last ice age (10,000 to site is a state wildlife management 12,000 years ago), a great lake area; and NWR stands for national stretched from Wheaton, Minn., to the JULY-AUGUST 1990 31 Our Prairie Heritage sandy beach ridges of Glacial Lake Agassiz. -

Minnesota State Parks.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Afton State Park 4 2. Banning State Park 6 3. Bear Head Lake State Park 8 4. Beaver Creek Valley State Park 10 5. Big Bog State Park 12 6. Big Stone Lake State Park 14 7. Blue Mounds State Park 16 8. Buffalo River State Park 18 9. Camden State Park 20 10. Carley State Park 22 11. Cascade River State Park 24 12. Charles A. Lindbergh State Park 26 13. Crow Wing State Park 28 14. Cuyuna Country State Park 30 15. Father Hennepin State Park 32 16. Flandrau State Park 34 17. Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park 36 18. Fort Ridgely State Park 38 19. Fort Snelling State Park 40 20. Franz Jevne State Park 42 21. Frontenac State Park 44 22. George H. Crosby Manitou State Park 46 23. Glacial Lakes State Park 48 24. Glendalough State Park 50 25. Gooseberry Falls State Park 52 26. Grand Portage State Park 54 27. Great River Bluffs State Park 56 28. Hayes Lake State Park 58 29. Hill Annex Mine State Park 60 30. Interstate State Park 62 31. Itasca State Park 64 32. Jay Cooke State Park 66 33. John A. Latsch State Park 68 34. Judge C.R. Magney State Park 70 1 35. Kilen Woods State Park 72 36. Lac qui Parle State Park 74 37. Lake Bemidji State Park 76 38. Lake Bronson State Park 78 39. Lake Carlos State Park 80 40. Lake Louise State Park 82 41. Lake Maria State Park 84 42. Lake Shetek State Park 86 43. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota By RICHARD FOSTER FLINT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Prepared as part of the program of the Department of the Interior *Jfor the development-L of*J the Missouri River basin UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $3 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ _ _____-_-_________________--_--____---__ 1 Pre- Wisconsin nonglacial deposits, ______________ 41 Scope and purpose of study._________________________ 2 Stratigraphic sequence in Nebraska and Iowa_ 42 Field work and acknowledgments._______-_____-_----_ 3 Stream deposits. _____________________ 42 Earlier studies____________________________________ 4 Loess sheets _ _ ______________________ 43 Geography.________________________________________ 5 Weathering profiles. __________________ 44 Topography and drainage______________________ 5 Stream deposits in South Dakota ___________ 45 Minnesota River-Red River lowland. _________ 5 Sand and gravel- _____________________ 45 Coteau des Prairies.________________________ 6 Distribution and thickness. ________ 45 Surface expression._____________________ 6 Physical character. _______________ 45 General geology._______________________ 7 Description by localities ___________ 46 Subdivisions. ________-___--_-_-_-______ 9 Conditions of deposition ___________ 50 James River lowland.__________-__-___-_--__ 9 Age and correlation_______________ 51 General features._________-____--_-__-__ 9 Clayey silt. __________________________ 52 Lake Dakota plain____________________ 10 Loveland loess in South Dakota. ___________ 52 James River highlands...-------.-.---.- 11 Weathering profiles and buried soils. ________ 53 Coteau du Missouri..___________--_-_-__-___ 12 Synthesis of pre- Wisconsin stratigraphy. -

S`Jt≈J`§≈J`§ ¢`§Mnln”D: the EVERCHANGING PIPESTONE QUARRIES

The Everchanging Pipestone Quarries Sioux Cultural Landscapes and Ethnobotany of Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota Item Type Report Authors Toupal, Rebecca; Stoffle, Richard, W.; O'Meara, Nathan; Dumbauld, Jill Publisher Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona Download date 05/10/2021 14:10:29 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/292658 S`jt≈j`§≈j`§ ¢`§mnln”d: THE EVERCHANGING PIPESTONE QUARRIES SIOUX CULTURAL LANDSCAPES AND ETHNOBOTANY OF PIPESTONE NATIONAL MONUMENT, MINNESOTA Final Report June 30, 2004 Rebecca S. Toupal Richard W. Stoffle Nathan O’Meara Jill Dumbauld BUREAU OF APPLIED RESEARCH IN ANTHROPOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA S`jt≈j`§≈j`§ ¢`§mnln”d: THE EVERCHANGING PIPESTONE QUARRIES SIOUX CULTURAL LANDSCAPES AND ETHNOBOTANY OF PIPESTONE NATIONAL MONUMENT, MINNESOTA Final Report Prepared by Rebecca S. Toupal Richard W. Stoffle Nathan O’Meara and Jill Dumbauld Prepared for National Park Service Midwest Region Under Task Agreement 27 of Cooperative Agreement H8601010007 R.W. Stoffle and M. N. Zedeño, Principal Investigators Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology University of Arizona Tucson, AZ 86721 June 30, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE................................................................................................................................ iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................................................... vi STUDY OVERVIEW................................................................................................................1 -

Earth Sciences: Two-Ice-Lobe Model for Kansan Glaciation James S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies 1982 Earth Sciences: Two-Ice-Lobe Model For Kansan Glaciation James S. Aber Emporia State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas Aber, James S., "Earth Sciences: Two-Ice-Lobe Model For Kansan Glaciation" (1982). Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies. 490. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas/490 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Academy of Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1982. Transactions a/the Nebraska Academy a/Sciences, X:25-29. EARTH SCIENCES TWO-ICE-LOBE MODEL FOR KANSAN GLACIATION James S. Aber Geoscience Department Emporia State University Emporia, Kansas 66801 The Kansan glaciation should be representative of Early Pleisto western source area, the so-called Keewatin Center, in the cene glaciations in the Kansas-Nebraska-Iowa-Missouri region. It is region west of Hudson Bay. Frye and Leonard (1952: 11) often assumed the Kansan ice-sheet advanced as a single, broad lobe supported this concept on the basis of distribution of the coming from somewhere in Canada. This simple view contrasts with the known complexities of the younger Wisconsin glaciation, and indeed Sioux Quartzite, a common erratic derived mainly from east there is much evidence that the Kansan glaciation was equally complex. -

References Cited in Dakota Skipper and Poweshiek Skipperling Proposed Listing Rule

References Cited in Dakota skipper and Poweshiek skipperling proposed listing rule Bahm, M. A., T. G. Barnes, and K. C. Jensen. 2011. Restoring Native Plant Communities in Smooth Brome (Bromus inermis)– Dominated Grasslands. Invasive Plant Science and Management 4:239-250. Belcher, J. W. and S. D. Wilson. 1989. Leafy Spurge and the Species Composition of a Mixed- Grass Prairie. Journal of Range Management 42:172-175. Bess, J. A. 1988. An insect survey of eight fens in southern Michigan., Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, MI. Beyers, B. 2012. Killer in a Bottle? Household insecticides may play a role in declining bee populations. University of Minnesota. Blatchley, W. S. 1891. A catalogue of the butterflies known to occur in Indiana. Annual Report of the Indiana State Geologist 17:365-408. Boettcher, J. F., T. B. Bragg, and D. M. Sutherland. 1993. Floristic Diversity in Ten Tallgrass Prairie Remnants of Eastern Nebraska. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas/116 XX:33-40. Borkin, S. S. 1995. 1994 Ecological Studies of the Poweshiek Skipper (Oarisma poweshiek) in Wisconsin. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, WI. Borkin, S. S. 2000. Proposal for outplanting on a state natural area., Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, WI. Borkin, S. S. 1995. 1994 Ecological Studies of the Poweshiek Skipper (Oarisma poweshiek) in Wisconsin. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, WI. Borkin, S. 1996. Ecological studies of the Poweshiek skipper (Oarisma poweshiek) in Wisconsin -1995 Season Summary. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, WI. Bragg, T. B. 1995. The physical environment of Great Plains grasslands. Pages 11-37 in K. -

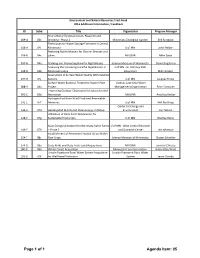

Of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd

Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund 2016 Additional Information / Feedback ID Subd. Title Organization Program Manager Prairie Butterfly Conservation, Research and 009‐A 03c Breeding ‐ Phase 2 Minnesota Zoological Garden Erik Runquist Techniques for Water Storage Estimates in Central 018‐A 04i Minnesota U of MN John Neiber Restoring Native Mussels for Cleaner Streams and 036‐B 04c Lakes MN DNR Mike Davis 037‐B 04a Tracking and Preventing Harmful Algal Blooms Science Museum of Minnesota Daniel Engstrom Assessing the Increasing Harmful Algal Blooms in U of MN ‐ St. Anthony Falls 038‐B 04b Minnesota Lakes Laboratory Miki Hondzo Assessment of Surface Water Quality With Satellite 047‐B 04j Sensors U of MN Jacques Finlay Surface Water Bacterial Treatment System Pilot Vadnais Lake Area Water 088‐B 04u Project Management Organization Brian Corcoran Improving Outdoor Classrooms for Education and 091‐C 05b Recreation MN DNR Amy Kay Kerber Hydrogen Fuel from Wind Produced Renewable 141‐E 07f Ammonia U of MN Will Northrop Center for Energy and 144‐E 07d Geotargeted Distributed Clean Energy Initiative Environment Carl Nelson Utilization of Dairy Farm Wastewater for 148‐E 07g Sustainable Production U of MN Bradley Heins Solar Energy Utilization for Minnesota Swine Farms U of MN ‐ West Central Research 149‐E 07h – Phase 2 and Outreach Center Lee Johnston Establishment of Permanent Habitat Strips Within 154‐F 08c Row Crops Science Museum of Minnesota Shawn Schottler 174‐G 09a State Parks and State Trails Land Acquisitions MN DNR Jennifer Christie 180‐G 09e Wilder Forest Acquisition Minnesota Food Association Hilary Otey Wold Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water System Acquisition Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water 181‐G 09f for Well Head Protection System Jason Overby Page 1 of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd.