A Call to Act.Witness.Testimony.Politicalrenewal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Perceived Alignment Between Managers' Words and Deeds As A

Behavioral Integrity: The Perceived Alignment Between Managers’ Words and Deeds as a Research Focus Tony Simons: Cornell University, School of Hotel Administration, Statler Hall 538, Ithaca, New York 4853-6902 Abstract This paper focuses on the perceived pattern of alignment between a manager's words and deeds, with special attention to promise keeping, and espoused and enacted values. It terms this perceived pattern of alignment "Behavioral Integrity." The literatures on trust, psychological contracts, and credibility combine to suggest important consequences for this perception, and literatures on hypocrisy, social accounts, social cognition, organizational change, and management fashions suggest key antecedents to it. The resulting conceptual model highlights an issue that is problematic in today's managerial environment, has important organizational outcomes, and is relatively unstudied. 1 A rapidly growing body of literature recognizes that trust plays a central role in employment relationships. Though scholars have varied somewhat in their specific definitions of trust, there is substantial agreement that a perception that another's words tend to align with his deeds is critically important for the development of trust (e.g., McGregor 1967). Credibility has received recent attention in the practitioner literature (Kouzes and Posner 1993) as a critical managerial attribute that is all too often undermined by managers' word-deed misalignment. In a similar vein, psychological contracts research has proliferated in recent years, due in part to its relevance in the recent managerial environment of widespread downsizing and restructuring because these processes are often understood by workers as violations of employers' commitments (Robinson 1996). This paper contends that the perceived pattern of managers' word- deed alignment or misalignment- with regard to a variety of issues-is it• self an important organizational phenomenon because it is a critical antecedent to trust and credibility. -

Words That Work: It's Not What You Say, It's What People Hear

ï . •,";,£ CASL M T. ^oÛNTAE À SUL'S, REVITA 1ENT, HASSLE- NT_ MAIN STR " \CCOUNTA ;, INNOVAT MLUE, CASL : REVITA JOVATh IE, CASL )UNTAE CO M M XIMEN1 VlTA • Ml ^re aW c^Pti ( °rds *cc Po 0 ^rof°>lish lu*t* >nk Lan <^l^ gua a ul Vic r ntz °ko Ono." - Somehow, W( c< Words are enorm i Jheer pleasure of CJ ftj* * - ! love laag^ liant about Words." gM °rder- Franl< Luntz * bril- 'Frank Luntz understands the power of words to move public Opinion and communicate big ideas. Any Democrat who writes off his analysis and decades of experience just because he works for the other side is making a big mistake. His les sons don't have a party label. The only question is, where s our Frank Luntz^^^^^^^™ îy are some people so much better than others at talking their way into a job or nit of trouble? What makes some advertising jingles cut through the clutter of our crowded memories? What's behind winning campaign slogans and career-ending political blunders? Why do some speeches resonate and endure while others are forgotten moments after they are given? The answers lie in the way words are used to influence and motivate, the way they connect thought and emotion. And no person knows more about the intersection of words and deeds than language architect and public-opinion guru Dr. Frank Luntz. In Words That Work, Dr. Luntz not only raises the curtain on the craft of effective language, but also offers priceless insight on how to find and use the right words to get what you want out of life. -

Consistency of Words and Deeds

that, while human nature had rotted from sin, Christ came, and His achievement was to deliver it from the rottenning of sins. While calling Christians salt, He showed that He entrusts to them as a painful care, that humanity not return again to rottening. So what is sought for, is our response to the title of Christian faith, in a manner in which we will honor and not undermine it. The value of Christianity is inconceivably great for the demeriting of the falls of Christians to undermine, and so for this reason it is 63RD YEAR OCTOBER 18, 2015 PAMPHLET # 42 (3255) something for which we will give account! CONSISTENCY OF WORDS AND DEEDS Archimandrite I. N When our Christ wanted to focus His people’s attention of on the necessity of being distinguished by consistency of words and deeds, He spoke about the majesty of spiritual life, but also about the tragedy of spiritually missing the mark, mainly as regards its effect on the rest of the people. “Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith shall it be salted? it is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to SUNDAY, OCTOBER 18 , Luke the Evangelist, Marinos the Martyr be trodden under foot of men.” (Mt. 5:13). In other words, you TONE OF THE WEEK: Tone Third disciples of Mine are the spiritual salt of people on the earth, EOTHINON Nineth Eothinon because you have the destiny of making life pleasant and of EPISTLE St. Paul's Letter to the Colossians 4:5-11, 14-18 preventing moral and spiritual rottenning. -

Words and Deeds Truly Please Our Lord

This book is a must-read. The quotations from experts in many fields are priceless. The reader will meet himself or herself several times in this book, and each meeting will leave the reader a better person who understands others better. Regardless of whether you are an employer or employee, military or civilian, you will be a better person after applying the insights in this book, and consequently, you’ll better perform the job with which you have been entrusted. LT. JIM DOWNING, author of The Other Side of Infamy As a pastor who wants to equip the men in my church to better serve their God, Christ’s church, their families, and our community, I’m so grateful for this book and Charles Causey’s practical, engaging, and scriptural call for men to live congruent lives—lives where our words and deeds truly please our Lord. ARRON CHAMBERS, pastor and author, Eats with Sinners: Loving like Jesus Our own fathers or grandfathers may not have needed this book. But we do. I do. We live in an age of spin. Talking a good game matters more than living a good life, and the art of persuasion is more valued than plain speech and honest action. Charles Causey steps into the muddle and issues a clear call for men to say what we mean, mean what we say, and do what we promise. It’s too bad we need this reminder. But it’s so good that it comes in this form— so clear, so simple, so sane, so direct. -

Crime, Media, Culture

Crime, Media, Culture http://cmc.sagepub.com/ Shakespeare and criminology Jeffrey R. Wilson Crime Media Culture 2014 10: 97 originally published online 18 June 2014 DOI: 10.1177/1741659014537655 The online version of this article can be found at: http://cmc.sagepub.com/content/10/2/97 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Crime, Media, Culture can be found at: Email Alerts: http://cmc.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://cmc.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav OnlineFirst Version of Record - Jun 18, 2014 What is This? Downloaded from cmc.sagepub.com by guest on August 20, 2014 CMC0010.1177/1741659014537655Crime Media CultureWilson 537655research-article2014 Article Crime Media Culture 2014, Vol. 10(2) 97 –114 Shakespeare and criminology © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1741659014537655 cmc.sagepub.com Jeffrey R. Wilson Harvard University, USA Abstract This paper suggests that Shakespeare’s plays offer an embryonic version of criminology, and that they remain a valuable resource for the field, both a theoretical and a pedagogical resource. On the one hand, for criminology scholars, Shakespeare can open up new avenues of theoretical consideration, for the criminal events depicted in his plays reflect complex philosophical debates about crime and justice, making interpretations of those events inherently theoretical; reading a passage from Shakespeare can be the first step in building a new theory of criminology. On the other hand, for criminology students, Shakespeare can initiate and sustain an intellectual transition that is fundamental to their professionalization, namely the transition from what I call a “simplistic” to a “skeptical” model of criminology. -

The House Oflovely Tull 5 Gibbs '

Thursday, March 22, 4 THE SPOK NE WOMAN 1928 SHORT SERMON FOR LENT Why Westmore Teachers’ Agency By Rev. Louis B. Egan, S. J. Imitation the highest form of praise. Christinns—followers of Chrisi Can Serve YOU Better —xseeking to imitate His example, conforming in a limited way their lives to on earth in Gallilee! His withdrawal for forty days snd nighis His days | Large Western Agency | Attractive Vacancies of fasting and prayer in the desert. The Christian curtailing even Reported Early certain legitimate pleasures and adding self-imposed vesirictions the nore {l Fourteen Years of to prove fealty to the Way, the Truth and the Life. Experience Used by Western The tilled fields reclothe the barredess of wiater with foilage of Superintendents by {| Abundant Direct Calls . .. strives repair sensons of negleet and apathy green, . , The soul to | Many Teachers Promoted turning again to its duties to God and affuirs spiritual, . Habits un- for Teachers worthy of a Christian to be lopped off; Thoughts, words and deeds des- tined to bring forth a rieh harvest to be impianied in their place, the tider FREE REGISTRATION benefitting by the universal spirit spurred on by the example of others Main of prayer and abnegation occasoined by the season of Lent. 715-716 Old National Bank Bldg. 3169 Even the most delectable pleasures pei! if incessant. ... To impose SPOKANE, WASH. some sacrifices on oneself during a few weeks should not prove too onerous, necessity Such a change is salutary, even in the natura! ovder, but of a where Greedy enchancing # the welfare of the soui is concerned. -

Words and Deeds

CRAINSNEW YORK BUSINESS NEW YORK BUSINESS Midtown East’s biggest landlords P. 6 | NYU’s answer to Cornell Tech P. 12 | Local bakers on the rise P. 26 CRAINS NEW YORK BUSINESS® SEPTEMBER 11 - 17, 2017 | PRICE $3.00 WORDS AND DEEDS VOL. XXXIII, NO. 37 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM Candidate Bill de Blasio pledged bold changes that would benet “all New Yorkers.” Our annual Stats and the City issue examines how well Mayor de Blasio delivered on those promises PAGE 14 NEWSPAPER P001_CN_20170911.indd 1 9/8/17 4:13 PM TWO • NINETY • TWO MADISON AVENUE Owner: Exclusive Leasing Agent: CN018347.indd 1 8/31/17 12:33 PM SEPTEMBER 11 - 17, 2017 CRAINSNEW YORK BUSINESS FROM THE NEWSROOM | JEREMY SMERD | EDITOR IN THIS ISSUE No longer just an island 4 AGENDA 5 IN CASE YOU MISSED IT THIS WEEK MARKS the ocial opening of Cornell Tech’s 6 WHO OWNS THE BLOCK A new tool campus on Roosevelt Island and a major milestone in the could help evolution of New York’s tech sector. If you haven’t been to 7 REAL ESTATE you save 8 ASKED & ANSWERED money on the campus yet, go. (You can now get there by ferry, in addi- medical bills. tion to the F line and the tram.) 9 HEALTH CARE I was there a few weeks ago to see the rst three build- 10 VIEWPOINTS ings on the 12-acre campus, which has turned the island FEATURES into a destination. ese buildings—the House, a luxurious apartment tower for students and faculty; the Bridge, which 12 NYU’S TECH EXPANSION has spaces for both instruction and collaboration; and the 14 STATS AND THE CITY Bloomberg Center, an academic building funded in large In the six years it 24 STEERING UBER part by the former mayor—total 850,000 square feet. -

Aesthetic Interpretation and the Claim to Community in Cavell

CONVERSATIONS 5 Seeing Selves and Imagining Others: Aesthetic Interpretation and the Claim to Community in Cavell JON NAJARIAN Politics is aesthetic in principle. JACQUES RANCIÈRE From his early childhood, Stanley Cavell learned to tread carefully the intervening space between twin pillars: of aesthetic sensibility on the one hand, and political be- longing on the other. Early in his memoir Little Did I Know, Cavell establishes a set of differences between his mother and father that far exceed both gender and age (his father was ten years older than his mother), as he notes the starkly contrasting dis- pensations of their respective families: The artistic temperament of my mother’s family, the Segals, left them on the whole, with the exception of my mother and her baby brother, Mendel, doubt- fully suited to an orderly, successful existence in the new world; the orthodox, religious sensibility of my father’s family, the Goldsteins, produced a second generation—some twenty-two first cousins of mine—whose solidarity and se- verity of expectation produced successful dentists, lawyers, and doctors, pillars of the Jewish community, and almost without exception attaining local, some of them national, some even a certain international, prominence.1 From his mother’s family, Cavell would inherit the musical sensibility that, had he not ventured into the world of academic philosophy, might have led him towards a career as a musician or in music. In his father’s family Cavell observes a religious belonging that, in the decades in which Cavell is raised, becomes morally inseparable from politi- $1. Cavell, Little Did I Know: Excerpts from Memory (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010), 3. -

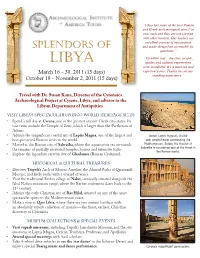

Splendors of and Made Themselves Accessible for Questions.”

“Libya has some of the best Roman and Greek archaeological sites I’ve ever seen and they are not overrun with other tourists. Our leaders are excellent sources of information SplendorS of and made themselves accessible for questions.” “Excellent tour—the sites, people, libya guides and cultural experiences were wonderful. It’s a must see and March 16 – 30, 2011 (15 days) experience tour. Thanks for an out- October 19 – November 2, 2011 (15 days) standing experience.” Travel with Dr. Susan Kane, Director of the Cyrenaica Archaeological Project at Cyrene, Libya, and advisor to the Libyan Department of Antiquities. VISIT LIBYA’S SPECTACULAR UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITES: • Spend a full day at Cyrene, one of the greatest ancient Greek city-states. Its vast ruins include the Temple of Zeus, which is larger than the Parthenon of Athens. • Admire the magnificent coastal site of Leptis Magna, one of the largest and Above, Leptis Magna’s 16,000 seat amphitheater overlooking the best-preserved Roman cities in the world. Mediterranean. Below, the theater at • Marvel at the Roman city of Sabratha, where the aquamarine sea surrounds Sabratha is considered one of the finest in the remains of partially excavated temples, houses and extensive baths. the Roman world. • Explore the legendary caravan city of Ghadames (Roman Cydamus). HISTORICAL & CULTURAL TREASURES • Discover Tripoli’s Arch of Marcus Aurelius, the Ahmad Pasha al Qaramanli Mosque, and lively souks with a myriad of wares. • Visit the traditional Berber village of Nalut, scenically situated alongside the Jabal Nafusa mountain range, where the Berber settlement dates back to the 11th century. -

Naked and Unashamed: a Study of the Aphrodite

Naked and Unashamed: A Study of the Aphrodite Anadyomene in the Greco-Roman World by Marianne Eileen Wardle Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Sheila Dillon, Supervisor ___________________________ Mary T. Boatwright ___________________________ Caroline A. Bruzelius ___________________________ Richard J. Powell ___________________________ Kristine Stiles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosopy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 ABSTRACT Naked and Unashamed: A Study of the Aphrodite Anadyomene in the Greco-Roman World by Marianne Eileen Wardle Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Sheila Dillon, Supervisor ___________________________ Mary T. Boatwright ___________________________ Caroline A. Bruzelius ___________________________ Richard J. Powell ___________________________ Kristine Stiles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosopy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright by Marianne Eileen Wardle 2010 Abstract This dissertation presents a study of the Aphrodite Anadyomene type in its cultural and physical contexts. Like many other naked Aphrodites, the Anadyomene was not posed to conceal the body, but with arms raised, naked and unashamed, exposing the goddess’ body to the gaze. Depictions of the Aphrodite Anadyomene present the female body as an object to be desired. The Anadyomene offers none of the complicated games of peek-a- boo which pudica Venuses play by shielding their bodies from view. Instead, the goddess offers her body to the viewer’s gaze and there is no doubt that we, as viewers, are meant to look, and that our looking should produce desire. -

Art and Emancipation: Habermas's

New German Critique Art and Emancipation: Habermas’s “Die Moderne— ein unvollendetes Projekt” Reconsidered Gili Kliger The Fate of Aesthetics While, by Habermas’s own admission, his remarks on aesthetic modernity always had a “secondary character to the extent that they arose only in the context of other themes,” aesthetics and aesthetic modernity do occupy an important position in his overall oeuvre.1 Much of Habermas’s work is charac- terized by an effort to restore the modern faith in reason first articulated by Enlightenment thinkers. It was, on Habermas’s terms, problematic that the cri- tique of reason launched by the first generation of Frankfurt School theorists, notably Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer, left them without a basis on which any reasoned critique of society could be pursued.2 For those theo- rists, Adorno especially, aesthetic experience held the promise of a reconciled relation between the sensual and the rational, posing as an “other” to the dom- inating force of instrumental reason in modern society and offering a way to I wish to thank Martin Ruehl, the Department of German at the University of Cambridge, Peter Gordon, John Flower, and the anonymous reviewers for their indispensable guidance and helpful suggestions. 1. Jürgen Habermas, “Questions and Counterquestions,” in Habermas and Modernity, ed. Rich- ard J. Bernstein (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985), 199. 2. Jürgen Habermas, Der philosophische Diskurs der Moderne (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1985), 138–39. New German Critique 124, Vol. 42, No. 1, February -

The Fear of Aesthetics in Art and Literary Theory Sam Rose

The Fear of Aesthetics in Art and Literary Theory Sam Rose New Literary History, Volume 48, Number 2, Spring 2017, pp. 223-244 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2017.0011 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/663805 Access provided at 2 May 2019 15:33 GMT from University of St Andrews The Fear of Aesthetics in Art and Literary Theory Sam Rose eading the preface to the new edition of the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, one might think that the battle over the status of aes- Rthetics is over. According to the narrative of its editor Michael Kelly, aesthetics, held in generally low esteem at the time of the 1998 first edition, has now happily overcome its association with “an alleg- edly retrograde return to beauty,” or its representation as “an ideology defending the tastes of a dominant class, country, race, gender, sexual preference, ethnicity, or empire.”1 The previously “rather pervasive anti- aesthetic stance” of the 1990s passed away with that decade.2 Defined as “critical reflection on art, culture, and nature,” aesthetics is now a respectable practice once again.3 The publication of the Encyclopedia’s latest iteration is a timely moment to review the current state of its much-maligned subject. The original edi- tion of 1998 faced major difficulties, with Kelly writing that his requests for contributions were greeted not only with silence from some, but also with responses from angry callers keen to tell him how misguided the entire project was.4 And while Kelly emphasizes the change toward a more positive view, in some critics, it seems, the fear of aesthetics in art and literary theory has only increased.