3 the Black Death in Norway: Arrival, Spread, Mortality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report and Sustainability Report 2019 2 01 Year 2019 02 About 03 Sustainability 04 Corporate 05 Directors’ Report and KONGSBERG Governance Financial Statements

ANNUAL REPORT AND SUSTAIN ABILITY REPORT 2019 01 Year 2019 02 About 03 Sustainability 04 Corporate 05 Directors’ Report and KONGSBERG Governance Financial Statements CORPORATE YEAR 2019 01 04 GOVERNANCE 4 Key Figures 2019 93 The Board’s Report on Corporate 7 Important milestones 2019 Governance 8 President and CEO Geir Håøy 94 Policy 95 Articles of Association 96 Board of Directors 97 The Board’s Report relating to “The Norwegian Code of Practice for Corporate Governance” DIRECTORS’ REPORT ABOUT KONGSBERG AND FINANCIAL 02 05 STATEMENTS 13 This is KONGSBERG 110 Directors’ Report 2019 15 Strategy and ambitions 128 Financial Statements and Notes 16 Vision 203 Statement from the Board 17 Our values 204 Auditor’s Report 2019 18 Corporate Executive Management 208 Financial calendar 19 Business areas 208 Contact details 29 The world of KONGSBERG 03 SUSTAINABILITY 36 About the Sustainability Report 41 Framework for the preparation of Sustainability Report 42 Organisation and Management Systems 43 Responsible Business Conduct 45 Responsible Tax – our Tax Policy 47 Focus areas 2019-2020 90 Auditor’s Report, Sustainability KONGSBERG Annual Report and Sustainability Report 2019 2 01 Year 2019 02 About 03 Sustainability 04 Corporate 05 Directors’ Report and KONGSBERG Governance Financial Statements Key Figures 2019 Important milestones 2019 President and CEO Geir Håøy 01 YEAR 2019 KONGSBERG Annual Report and Sustainability Report 2019 3 01 Year 2019 02 About 03 Sustainability 04 Corporate 05 Directors’ Report and KONGSBERG Governance Financial Statements -

Saami and Scandinavians in the Viking

Jurij K. Kusmenko Sámi and Scandinavians in the Viking Age Introduction Though we do not know exactly when Scandinavians and Sámi contact started, it is clear that in the time of the formation of the Scandinavian heathen culture and of the Scandinavian languages the Scandinavians and the Sámi were neighbors. Archeologists and historians continue to argue about the place of the original southern boarder of the Sámi on the Scandinavian peninsula and about the place of the most narrow cultural contact, but nobody doubts that the cultural contact between the Sámi and the Scandinavians before and during the Viking Age was very close. Such close contact could not but have left traces in the Sámi culture and in the Sámi languages. This influence concerned not only material culture but even folklore and religion, especially in the area of the Southern Sámi. We find here even names of gods borrowed from the Scandinavian tradition. Swedish and Norwegian missionaries mentioned such Southern Sámi gods such as Radien (cf. norw., sw. rå, rådare) , Veralden Olmai (<Veraldar goð, Frey), Ruona (Rana) (< Rán), Horagalles (< Þórkarl), Ruotta (Rota). In Lule Sámi we find no Scandinavian gods but Scandinavian names of gods such as Storjunkare (big ruler) and Lilljunkare (small ruler). In the Sámi languages we find about three thousand loan words from the Scandinavian languages and many of them were borrowed in the common Scandinavian period (550-1050), that is before and during the Viking Age (Qvigstad 1893; Sammallahti 1998, 128-129). The known Swedish Lapponist Wiklund said in 1898 »[...] Lapska innehåller nämligen en mycket stor mängd låneord från de nordiska språken, av vilka låneord de äldsta ovillkorligen måste vara lånade redan i urnordisk tid, dvs under tiden före ca 700 år efter Kristus. -

Product Manual

PRODUCT MANUAL The Sami of Finnmark. Photo: Terje Rakke/Nordic Life/visitnorway.com. Norwegian Travel Workshop 2014 Alta, 31 March-3 April Sorrisniva Igloo Hotel, Alta. Photo: Terje Rakke/Nordic Life AS/visitnorway.com INDEX - NORWEGIAN SUPPLIERS Stand Page ACTIVITY COMPANIES ARCTIC GUIDE SERVICE AS 40 9 ARCTIC WHALE TOURS 57 10 BARENTS-SAFARI - H.HATLE AS 21 14 NEW! DESTINASJON 71° NORD AS 13 34 FLÅM GUIDESERVICE AS - FJORDSAFARI 200 65 NEW! GAPAHUKEN DRIFT AS 23 70 GEIRANGER FJORDSERVICE AS 239 73 NEW! GLØD EXPLORER AS 7 75 NEW! HOLMEN HUSKY 8 87 JOSTEDALSBREEN & STRYN ADVENTURE 205-206 98 KIRKENES SNOWHOTEL AS 19-20 101 NEW! KONGSHUS JAKT OG FISKECAMP 11 104 LYNGSFJORD ADVENTURE 39 112 NORTHERN LIGHTS HUSKY 6 128 PASVIKTURIST AS 22 136 NEW! PÆSKATUN 4 138 SCAN ADVENTURE 38 149 NEW! SEIL NORGE AS (SAILNORWAY LTD.) 95 152 NEW! SEILAND HOUSE 5 153 SKISTAR NORGE 150 156 SORRISNIVA AS 9-10 160 NEW! STRANDA SKI RESORT 244 168 TROMSØ LAPLAND 73 177 NEW! TROMSØ SAFARI AS 48 178 TROMSØ VILLMARKSSENTER AS 75 179 TRYSILGUIDENE AS 152 180 TURGLEDER AS / ENGHOLM HUSKY 12 183 TYSFJORD TURISTSENTER AS 96 184 WHALESAFARI LTD 54 209 WILD NORWAY 161 211 ATTRACTIONS NEW! ALTA MUSEUM - WORLD HERITAGE ROCK ART 2 5 NEW! ATLANTERHAVSPARKEN 266 11 DALSNIBBA VIEWPOINT 1,500 M.A.S.L 240 32 DESTINATION BRIKSDAL 210 39 FLØIBANEN AS 224 64 FLÅMSBANA - THE FLÅM RAILWAY 229-230 67 HARDANGERVIDDA NATURE CENTRE EIDFJORD 212 82 I Stand Page HURTIGRUTEN 27-28 96 LOFOTR VIKING MUSEUM 64 110 MAIHAUGEN/NORWEGIAN OLYMPIC MUSEUM 190 113 NATIONAL PILGRIM CENTRE 163 120 NEW! NORDKAPPHALLEN 15 123 NORWEGIAN FJORD CENTRE 242 126 NEW! NORSK FOLKEMUSEUM 140 127 NORWEGIAN GLACIER MUSEUM 204 131 STIFTELSEN ALNES FYR 265 164 CARRIERS ACP RAIL INTERNATIONAL 251 2 ARCTIC BUSS LOFOTEN 56 8 AVIS RENT A CAR 103 13 BUSSRING AS 47 24 COLOR LINE 107-108 28 COMINOR AS 29 29 FJORD LINE AS 263-264 59 FJORD1 AS 262 62 NEW! H.M. -

Beinfunn Og Observasjoner Av Villsvin I Østfold GEIR HARDENG

Beinfunn og observasjoner av villsvin i Østfold GEIR HARDENG Hardeng, G. 2004. Beinfunn og observasjoner av villsvin i Østfold. Natur i Østfold 23(1-2): 14-17. Det gis en kort oversikt over sikre og mer usikre beinfunn av villsvin i Østfold, antatt fra yngre steinalder. I Østfold fi nnes ikke veideristninger etter steinalder-fangstmannens byttedyr. Her er jordbruksristninger enerådende. En bronsealder-ristning fra Skjeberg kan mulig tolkes som svin. Noen observasjoner av ville dyr foreligger fra Idd, Halden i 1994, antatt dyr kommer over fra Sverige. Villsvin og hybridsvin (tamsvin x villsvin) kan også opptre. Arten er utsatt i Sverige i ny tid, men er uønsket i Norge. Geir Hardeng, Fuglevik platå 19, 1673 Kråkerøy. e-post: [email protected] Innvandring Villsvinet Sus scrofa antas å ha innvandret til Norge således ikke til stede ved beinfunn fra boplasser via Danmark og Mellom-Sverige i begynnelsen fra yngre steinalder i Østfold. av postglacial varmetid etter istiden, da også en På en steinalder-boplass med funn av rekke varmkjære plantearter, den såkalte kristtorn- hasselnøtter datert til ca 6.200 f. Kr. ved Tørkop fl oraen, bokstavelig talt slo rot i Norge (Collett i Idd, Halden, ble det i 1974 gjort beinfunn av svin 1911-12). Villsvinet var utbredt i kyststrøk av (Sørensen 1974). Dateringen tilsvarer slutten av Sør-Norge i steinalderens varmere perioder, i boreal tid, nettopp i den mest hasselrike perioden såkalt atlantisk tid (Tapes-tiden) for ca. 7000 år i Idd (Mikkelsen 1975). siden. Arten var den gang et viktig jaktobjekt og var knyttet til varmekjær edelløvskog, særlig eik- og hasselskog, som den gang hadde en langt videre utbredelse enn nå. -

Stortingsvalget 1965. Hefte II Oversikt

OGES OISIEE SAISIKK II 199 SOIGSAGE 6 EE II OESIK SOIG EECIOS 6 l II Gnrl Srv SAISISK SEAYÅ CEA UEAU O SAISICS O OWAY OSO 66 Tidligere utkommet. Statistik vedkommende Valgmandsvalgene og Stortingsvalgene 1815-1885: NOS III 219, 1888: Medd. fra det Statist. Centralbureau 7, 1889, suppl. 2, 1891: Medd. fra det Statist. Centralbureau 10, 1891, suppl. 2, 1894 III 245, 1897 III 306, 1900 IV 25, 1903 IV 109. Stortingsvalget 1906 NOS V 49, 1909 V 128, 1912 V 189, 1915 VI 65, 1918 VI 150, 1921 VII 66, 1924 VII 176, 1927 VIII 69, 1930 VIII 157, 1933 IX 26, 1936 IX 107, 1945 X 132, 1949 XI 13, 1953 XI 180, 1957 XI 299, 1961 XII 68, 1961 A 126. Stortingsvalget 1965 I NOS A 134. MARIENDALS BOKTRYKKERI A/S, GJØVIK Forord I denne publikasjonen er det foretatt en analyse av resultatene fra stortings- valget 1965. Opplegget til analysen er stort sett det samme som for stortings- valget 1961 og bygger på et samarbeid med Chr. Michelsens Institutt og Institutt for Samfunnsforskning. Som tillegg til oversikten er tatt inn de offisielle valglister ved stortingsvalget i 1965. Detaljerte talloppgaver fra stortingsvalget er offentliggjort i Stortingsvalget 1965, hefte I (NOS A 134). Statistisk Sentralbyrå, Oslo, 1. juni 1966. Petter Jakob Bjerve Gerd Skoe Lettenstrom Preface This publication contains a survey of the results of the Storting elections 1965. The survey appears in approximately the same form as the survey of the 1961 elections and has been prepared in co-operation with Chr. Michelsen's Institute and the Institute for Social Research. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2021

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2021 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. The Prayer Diary is updated once a year. For corrections and updates, please contact Ecumenical Officer, Maria Bergstrand, Ms., Stockholm Diocese, Church of Sweden, E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 3/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Sarah Mullally, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe, Bishop Joanne Grenfell. Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Olav Fykse Tveit, Bishop Herborg Oline Finnset 10/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Jukka Keskitalo Church of Norway: Diocese of Sør-Hålogaland (Bodø), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

Download the Full Reportpdf, 6.1 MB

VKM Report 2018: 16 Factors that can contribute to spread of CWD – an update on the situation in Nordfjella, Norway Opinion of the Panel on biological hazards of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment Report from the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment (VKM) 2018: 16 Factors that can contribute to spread of CWD – an update on the situation in Nordfjella, Norway Opinion of Panel on biological hazards of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment 13.12.2018 ISBN: 978-82-8259-316-8 ISSN: 2535-4019 Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment (VKM) Po 222 Skøyen 0213 Oslo Norway Phone: +47 21 62 28 00 Email: [email protected] vkm.no vkm.no/English Cover photo: Wild reindeer visiting a mineral lick in early spring. Aerial photo by Roy Andersen, NINA. Suggested citation: VKM, Bjørnar Ytrehus, Danica Grahek-Ogden, Olav Strand, Michael Tranulis, Atle Mysterud, Marina Aspholm, Solveig Jore, Georg Kapperud, Trond Møretrø, Truls Nesbakken, Lucy Robertson, Kjetil Melby, Taran Skjerdal. (2018) Factors that can contribute to spread of CWD – an update on the situation in Nordfjella, Norway. Opinion of the Panel on biological hazards. ISBN: 978-82-8259-316-8. Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment (VKM), Oslo, Norway. VKM Report 2018: 16 Factors that can contribute to spread of CWD – an update on the situation in Nordfjella, Norway Preparation of the opinion The Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment (Vitenskapskomiteen for mat og miljø, VKM) appointed a project group to answer the request from the Norwegian Food Safety Authority. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2021

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2021 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. The Prayer Diary is updated once a year. For corrections and updates, please contact Ecumenical Officer, Cajsa Sandgren, Ms., Ecumenical Department, Church of Sweden, E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 10/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Sarah Mullally, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe, Bishop Joanne Grenfell. Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Olav Fykse Tveit, Bishop Herborg Oline Finnset 17/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Jukka Keskitalo Church of Norway: Diocese of Sør-Hålogaland (Bodø), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

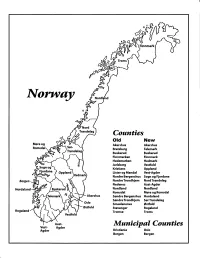

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Annual Report 2015 / 10-Year Anniversary Booklet

DEMOCRACY BUILDING IN A TURBULENT WORLD THE OSLO CENTER 10 YEAR ANNIVERSARY 2006 – 2016 Peace Democracy Human Rights CONTENT FOREWORD PAGE 5 INTRODUCTION PAGE 6 THE VISION BEHIND THE OSLO CENTER PAGE 6 MAKING IDEAS FLY PAGE 7 THE WAY FORWARD PAGE 9 DEMOCRACY ASSISTANCE PAGE 10 THE OSLO CENTER APPROACH PAGE 17 ARTICLES PAGE 19 HUMAN RIGHTS IN NORWAY’S FOREIGN AND DEVELOPMENT POLICY PAGE 19 INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE PAGE 24 CURRENT PROJECTS PAGE 31 SOMALIA – Small but important steps towards democracy PAGE 31 KENYA – Strengthening democratic processes PAGE 33 SOUTH SUDAN – Youth dialogue as a way to inclusive participation PAGE 36 BURMA/MYANMAR – Youth engagement: a prerequisite for democracy PAGE 38 NEPAL – Strengthening democracy through effective implementation of the new Constitution PAGE 41 UKRAINE – Cross party cooperation and coalition building PAGE 42 THE KYRGYZ REPUBLIC - Strengthening democratic processes and human rights PAGE 45 SUSTAINABLE MANGEMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES - Underpinning democracy and economic growth PAGE 46 THE UNIVERSAL CODE OF CONDUCT ON HOLY SITES – Inter-religious efforts to protect holy sites PAGE 48 CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT – Oslo Center publications, handbooks and guides PAGE 50 FORMER PROJECTS PAGE 54 UN MISSION TO THE HORN OF AFRICA - Special Humanitarian Envoy to the region PAGE 54 DIALOGUE FOR RESPECT AND UNDERSTANDING – The islamic world and the west PAGE 56 RELIGION AND DEVELOPMENT - Greater expertize needed on how religion influences societal development PAGE 58 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT ON ERITREA - Report on -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Habituation Responses in Wild Reindeer Exposed to Recreational Activities

Habituation responses in wild reindeer exposed to recreational activities Eigil Reimers1,2, Knut H. Røed2, Øystein Flaget3, & Eivind Lurås3 1 Department of Biology, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1066 Blindern, 0316 Oslo, Norway ([email protected]). 2 Department of Basic Sciences and Aquatic Medicine, The Norwegian School of Veterinary Science, P.O. Box 8146 Dep., 0033 Oslo, Norway. 3 Høgskolen i Hedmark, Avdeling for skog- og utmarksfag, Evenstad, Norway. Abstract: Displacement is the effect most often predicted when recreational activities in wild reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) areas are discussed. Wild reindeer in Blefjell (225 km2) are exposed to humans more frequently than in Har- dangervidda (8200 km2), from which the Blefjell herd originate. We recorded fright and flight response distances of groups of reindeer in both herds to a person directly approaching them on foot or skis during winter, summer, and autumn post-hunting and rutting season in 2004-2006. The response distances sight, alert, flight initiation and escape were shorter in Blefjell than in Hardangervidda while the probability of assessing the observer before flight tended to be greater in Blefjell. To test whether these results could be due to habituation or genetic influence of semi-domestic reindeer previously released in the Blefjell region, we compared the genetic variation of the Blefjell reindeer with previously reported variation in semi-domestic reindeer and in the wild reindeer from Hardangervidda. Microsatellite analyses revealed closer genetic ancestry of the Blefjell reindeer to the wild Hardangervidda reindeer and not to the semi-domestic reindeer at both the herd and the individual level.