Adapt to Changes: Lessons from Two Irrigation Systems in Ezhou, China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landscape Analysis of Geographical Names in Hubei Province, China

Entropy 2014, 16, 6313-6337; doi:10.3390/e16126313 OPEN ACCESS entropy ISSN 1099-4300 www.mdpi.com/journal/entropy Article Landscape Analysis of Geographical Names in Hubei Province, China Xixi Chen 1, Tao Hu 1, Fu Ren 1,2,*, Deng Chen 1, Lan Li 1 and Nan Gao 1 1 School of Resource and Environment Science, Wuhan University, Luoyu Road 129, Wuhan 430079, China; E-Mails: [email protected] (X.C.); [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (L.L.); [email protected] (N.G.) 2 Key Laboratory of Geographical Information System, Ministry of Education, Wuhan University, Luoyu Road 129, Wuhan 430079, China * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel: +86-27-87664557; Fax: +86-27-68778893. External Editor: Hwa-Lung Yu Received: 20 July 2014; in revised form: 31 October 2014 / Accepted: 26 November 2014 / Published: 1 December 2014 Abstract: Hubei Province is the hub of communications in central China, which directly determines its strategic position in the country’s development. Additionally, Hubei Province is well-known for its diverse landforms, including mountains, hills, mounds and plains. This area is called “The Province of Thousand Lakes” due to the abundance of water resources. Geographical names are exclusive names given to physical or anthropogenic geographic entities at specific spatial locations and are important signs by which humans understand natural and human activities. In this study, geographic information systems (GIS) technology is adopted to establish a geodatabase of geographical names with particular characteristics in Hubei Province and extract certain geomorphologic and environmental factors. -

Download Article

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 70 International Conference on Economy, Management and Entrepreneurship(ICOEME 2018) Research on the Path of Deep Fusion and Integration Development of Wuhan and Ezhou Lijiang Zhao Chengxiu Teng School of Public Administration School of Public Administration Zhongnan University of Economics and Law Zhongnan University of Economics and Law Wuhan, China 430073 Wuhan, China 430073 Abstract—The integration development of Wuhan and urban integration of Wuhan and Hubei, rely on and Ezhou is a strategic task in Hubei Province. It is of great undertake Wuhan. Ezhou City takes the initiative to revise significance to enhance the primacy of provincial capital, form the overall urban and rural plan. Ezhou’s transportation a new pattern of productivity allocation, drive the development infrastructure is connected to the traffic artery of Wuhan in of provincial economy and upgrade the competitiveness of an all-around and three-dimensional way. At present, there provincial-level administrative regions. This paper discusses are 3 interconnected expressways including Shanghai- the path of deep integration development of Wuhan and Ezhou Chengdu expressway, Wuhan-Ezhou expressway and from the aspects of history, geography, politics and economy, Wugang expressway. In terms of market access, Wuhan East and puts forward some suggestions on relevant management Lake Development Zone and Ezhou Gedian Development principles and policies. Zone try out market access cooperation, and enterprises Keywords—urban regional cooperation; integration registered in Ezhou can be named with “Wuhan”. development; path III. THE SPACE FOR IMPROVEMENT IN THE INTEGRATION I. INTRODUCTION DEVELOPMENT OF WUHAN AND EZHOU Exploring the path of leapfrog development in inland The degree of integration development of Wuhan and areas is a common issue for the vast areas (that is to say, 500 Ezhou is lower than that of central urban area of Wuhan, and kilometers from the coastline) of China’s hinterland. -

A Simple Model to Assess Wuhan Lock-Down Effect and Region Efforts

A simple model to assess Wuhan lock-down effect and region efforts during COVID-19 epidemic in China Mainland Zheming Yuan#, Yi Xiao#, Zhijun Dai, Jianjun Huang & Yuan Chen* Hunan Engineering & Technology Research Centre for Agricultural Big Data Analysis & Decision-making, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, Hunan, 410128, China. #These authors contributed equally to this work. * Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Y.C. (email: [email protected]) (Submitted: 29 February 2020 – Published online: 2 March 2020) DISCLAIMER This paper was submitted to the Bulletin of the World Health Organization and was posted to the COVID-19 open site, according to the protocol for public health emergencies for international concern as described in Vasee Moorthy et al. (http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.251561). The information herein is available for unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is properly cited as indicated by the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Intergovernmental Organizations licence (CC BY IGO 3.0). RECOMMENDED CITATION Yuan Z, Xiao Y, Dai Z, Huang J & Chen Y. A simple model to assess Wuhan lock-down effect and region efforts during COVID-19 epidemic in China Mainland [Preprint]. Bull World Health Organ. E-pub: 02 March 2020. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.254045 Abstract: Since COVID-19 emerged in early December, 2019 in Wuhan and swept across China Mainland, a series of large-scale public health interventions, especially Wuhan lock-down combined with nationwide traffic restrictions and Stay At Home Movement, have been taken by the government to control the epidemic. -

Research on Sustainable Land Use Based on Production–Living–Ecological Function: a Case Study of Hubei Province, China

sustainability Article Research on Sustainable Land Use Based on Production–Living–Ecological Function: A Case Study of Hubei Province, China Chao Wei 1, Qiaowen Lin 2, Li Yu 3,* , Hongwei Zhang 3 , Sheng Ye 3 and Di Zhang 3 1 School of Public Administration, Hubei University, Wuhan 430062, China; [email protected] 2 School of Management and Economics, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China; [email protected] 3 School of Public Administration, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430074, China; [email protected] (H.Z.); [email protected] (S.Y.); [email protected] (D.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-185-7163-2717 Abstract: After decades of rapid development, there exists insufficient and contradictory land use in the world, and social, economic and ecological sustainable development is facing severe challenges. Balanced land use functions (LUFs) can promote sustainable land use and reduces land pressures from limited land resources. In this study, we propose a new conceptual index system using the entropy weight method, regional center of gravity theory, coupling coordination degree model and obstacle factor identification model for LUFs assessment and spatial-temporal analysis. This framework was applied to 17 cities in central China’s Hubei Province using 39 indicators in terms of production–living–ecology analysis during 1996–2016. The result shows that (1) LUFs showed an overall upward trend during the study period, while the way of promotion varied with different dimensions. Production function (PF) experienced a continuous enhancement during the study period. Living function (LF) was similar in this aspect, but showed a faster rising tendency. -

Are China's Water Resources for Agriculture Sustainable? Evidence from Hubei Province

sustainability Article Are China’s Water Resources for Agriculture Sustainable? Evidence from Hubei Province Hao Jin and Shuai Huang * School of Public Economics and Administration, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, Shanghai 200433, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-21-65903686 Abstract: We assessed the sustainability of agricultural water resources in Hubei Province, a typical agricultural province in central China, for a decade (2008–2018). Since traditional evaluation models often consider only the distance between the evaluation point and the positive or negative ideal solution, we introduce gray correlation analysis and construct a new sustainability evaluation model. Our research results show that only one city had excellent sustainable development capacity of agricultural water resources, and the evaluation value of eight cities fluctuated by around 0.5 (the median of the evaluation result), while the sustainable development capacity of agricultural water resources in other cities was relatively poor. Our findings not only reflect the differences in the natural conditions of water resources among various cities in Hubei, but also the impact of the cities’ policies to ensure efficient agricultural water use for sustainable development. The indicators and methods Citation: Jin, H.; Huang, S. Are in this research are not difficult to obtain in most countries and regions of the world. Therefore, the China’s Water Resources for indicator system we have established by this research could be used to study the sustainability of Agriculture Sustainable? Evidence agricultural water resources in other countries, regions, or cities. from Hubei Province. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3510. https://doi.org/ Keywords: water resources; agricultural water resources; sustainability; gray correlation analysis; 10.3390/su13063510 evaluation model Academic Editors: Daniela Malcangio, Alan Cuthbertson, Juan 1. -

Three Kingdoms Unveiling the Story: List of Works

Celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the Japan-China Cultural Exchange Agreement List of Works Organizers: Tokyo National Museum, Art Exhibitions China, NHK, NHK Promotions Inc., The Asahi Shimbun With the Support of: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, NATIONAL CULTURAL HERITAGE ADMINISTRATION, July 9 – September 16, 2019 Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in Japan With the Sponsorship of: Heiseikan, Tokyo National Museum Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd., Notes Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance Co.,Ltd., MITSUI & CO., LTD. ・Exhibition numbers correspond to the catalogue entry numbers. However, the order of the artworks in the exhibition may not necessarily be the same. With the cooperation of: ・Designation is indicated by a symbol ☆ for Chinese First Grade Cultural Relic. IIDA CITY KAWAMOTO KIHACHIRO PUPPET MUSEUM, ・Works are on view throughout the exhibition period. KOEI TECMO GAMES CO., LTD., ・ Exhibition lineup may change as circumstances require. Missing numbers refer to works that have been pulled from the JAPAN AIRLINES, exhibition. HIKARI Production LTD. No. Designation Title Excavation year / Location or Artist, etc. Period and date of production Ownership Prologue: Legends of the Three Kingdoms Period 1 Guan Yu Ming dynasty, 15th–16th century Xinxiang Museum Zhuge Liang Emerges From the 2 Ming dynasty, 15th century Shanghai Museum Mountains to Serve 3 Narrative Figure Painting By Qiu Ying Ming dynasty, 16th century Shanghai Museum 4 Former Ode on the Red Cliffs By Zhang Ruitu Ming dynasty, dated 1626 Tianjin Museum Illustrated -

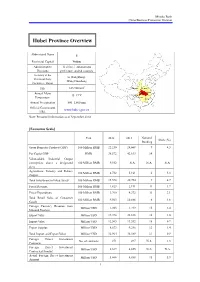

Hubei Province Overview

Mizuho Bank China Business Promotion Division Hubei Province Overview Abbreviated Name E Provincial Capital Wuhan Administrative 12 cities, 1 autonomous Divisions prefecture, and 64 counties Secretary of the Li Hongzhong; Provincial Party Wang Guosheng Committee; Mayor 2 Size 185,900 km Shaanxi Henan Annual Mean Hubei Anhui 15–17°C Chongqing Temperature Hunan Jiangxi Annual Precipitation 800–1,600 mm Official Government www.hubei.gov.cn URL Note: Personnel information as of September 2014 [Economic Scale] Unit 2012 2013 National Share (%) Ranking Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 100 Million RMB 22,250 24,668 9 4.3 Per Capita GDP RMB 38,572 42,613 14 - Value-added Industrial Output (enterprises above a designated 100 Million RMB 9,552 N.A. N.A. N.A. size) Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery 100 Million RMB 4,732 5,161 6 5.3 Output Total Investment in Fixed Assets 100 Million RMB 15,578 20,754 9 4.7 Fiscal Revenue 100 Million RMB 1,823 2,191 11 1.7 Fiscal Expenditure 100 Million RMB 3,760 4,372 11 3.1 Total Retail Sales of Consumer 100 Million RMB 9,563 10,886 6 4.6 Goods Foreign Currency Revenue from Million USD 1,203 1,219 15 2.4 Inbound Tourism Export Value Million USD 19,398 22,838 16 1.0 Import Value Million USD 12,565 13,552 18 0.7 Export Surplus Million USD 6,833 9,286 12 1.4 Total Import and Export Value Million USD 31,964 36,389 17 0.9 Foreign Direct Investment No. -

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data Figures Figure S1 Figure S1 Top cities with the highest migrants before Spring Festival A-C, Top cities with highest migrant on Jan 22, 2020. D-F, Top cities with highest migrant on Jan 23, 2020. G-I, Top cities with highest migrant on Jan 24, 2020. A, D, G, Top 50 hot cities with high export migrants; B, E, H, Top 10 cities with high export migrant; C, F, I, Top 10 cities with high import migrants. Figure S2 Figure S2 Migration and transport index during spring festival A, Emigration from Wuhan City on Jan 23, 2020; B, Emigration from Hubei province on Jan 23, 2020; C, Traffic congestion index during 7-day festival holiday in 2020 and 2019; D, Population mobility index during 7-day festival holiday in 2020 and 2019. Tables Table S1 Hot spot value and relative risk with case number and incidence Case Number Incidence City Name Hot value Relative Risk Hot value Relative Risk Trend Huanggang 0.7201 0.133 0.4678 0.485 Ezhou City 0.5833 0.346 0.4714 0.5067 Suizhou 0.4106 0.8371 0.4739 0.4732 Wuhan 0.7822 1.77E-04 0.4766 0.4987 Yellowstone 0.6053 0.4126 0.4822 0.4702 Xiangyang 0.3047 0.8646 0.4933 0.5275 Xiaogan 0.6284 0.536 0.4941 0.4689 Xianning 0.5739 0.5933 0.4946 0.484 Tianmen 0.4501 0.5174 0.5035 0.4792 Qianjiang 0.3958 0.4191 0.504 0.4736 Shiyan 0.3538 0.8206 0.5064 0.5596 Jingzhou 0.5947 0.2856 0.5101 0.4826 Xiantao 0.5631 0.1536 0.5115 0.4868 Jingmen 0.4774 0.7351 0.5278 0.501 Yichang 0.3634 0.7426 0.5324 0.5537 Enshi 0.369 0.7142 0.5378 0.5239 Table S2 Migration index of Wuhan city and Hubei province in 2020 and -

CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 2202)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 2202) 2019 ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors (the “Board”) of China Vanke Co., Ltd.* (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended 31 December 2019. This announcement, containing the full text of the 2019 Annual Report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcement of annual results. Printed version of the Company’s 2019 Annual Report will be delivered to the H-Share Holders of the Company and available for viewing on the websites of The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk) and of the Company (www.vanke.com) in April 2020. Both the Chinese and English versions of this results announcement are available on the websites of the Company (www.vanke.com) and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk). In the event of any discrepancies in interpretations between the English version and Chinese version, the Chinese version shall prevail, except for the financial report prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards, of which the English version shall prevail. -

Modelling the Effects of Wuhan's Lockdown During COVID-19, China

Research Modelling the effects of Wuhan’s lockdown during COVID-19, China Zheming Yuan,a Yi Xiao,a Zhijun Dai,a Jianjun Huang,a Zhenhai Zhangb & Yuan Chenb Objective To design a simple model to assess the effectiveness of measures to prevent the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) to different regions of mainland China. Methods We extracted data on population movements from an internet company data set and the numbers of confirmed cases of COVID-19 from government sources. On 23 January 2020 all travel in and out of the city of Wuhan was prohibited to control the spread of the disease. We modelled two key factors affecting the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in regions outside Wuhan by 1 March 2020: (i) the total the number of people leaving Wuhan during 20–26 January 2020; and (ii) the number of seed cases from Wuhan before 19 January 2020, represented by the cumulative number of confirmed cases on 29 January 2020. We constructed a regression model to predict the cumulative number of cases in non-Wuhan regions in three assumed epidemic control scenarios. Findings Delaying the start date of control measures by only 3 days would have increased the estimated 30 699 confirmed cases of COVID-19 by 1 March 2020 in regions outside Wuhan by 34.6% (to 41 330 people). Advancing controls by 3 days would reduce infections by 30.8% (to 21 235 people) with basic control measures or 48.6% (to 15 796 people) with strict control measures. Based on standard residual values from the model, we were able to rank regions which were most effective in controlling the epidemic. -

Comparing Chinese and United States Lake Management and Protection As Shared Through a Sister Lakes Program

Comparing Chinese and United States lake management and protection As shared through a sister lakes program Lake Pepin, Minnesota Liangzi Lake, Hubei Province Minnesota Pollution May 2016 Control Agency Authors Steven Heiskary Research Scientist III Water Quality Monitoring Unit Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, Zhiquan Chen Manager Hubei Province Department of Environmental Protection Yiluan Dong Environmental Protection Engineer Hubei Province Department of Environmental Protection Review Pam Anderson Water Quality Monitoring Unit Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Authors Steven Heiskary, Research Scientist III, Water Quality Monitoring Unit, Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Zhiquan Chen, Manager, Hubei Province Department of Environmental Protection Yiluan Dong, Registered Environmental Protection Engineer, Hubei Academy of Environmental Sciences, China Review Pam Anderson, Water Quality Monitoring Unit, Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Editing and graphic design Theresa Gaffey & Paul Andre Minnesota Pollution Control Agency 520 Lafayette Road North | Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 | | 800-657-3864 | Or use your preferred relay service. [email protected] 651-296-6300 | This report is available in alternative formats upon request, and online at www.pca.state.mn.us. Document number: wq-s1-91 Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Degree of Harmony of Urban Land Use and Economic Development: Case Study of Wuhan Metropolitan Area

Journal of Sustainable Development; Vol. 7, No. 4; 2014 ISSN 1913-9063 E-ISSN 1913-9071 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Degree of Harmony of Urban Land Use and Economic Development: Case Study of Wuhan Metropolitan Area Zhu Xiangbo1 & Tan Shukui1 1 College of Public Administration, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China Correspondence: Tan Shukui, College of Public Administration, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. Tel: 86-27-8755-9342. E-mail:[email protected]; [email protected] Received: May 12, 2014 Accepted: May 27, 2014 Online Published: July 31, 2014 doi:10.5539/jsd.v7n4p139 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v7n4p139 Abstract As urban land use is facing more and more severe sustainability challenges, it is essential to make effective and scientific evaluation on relationship between urban land use and economic development. With a series of indicators that drawn from previous literatures and data collected from Wuhan Metropolitan Area, this paper evaluated the degree of harmony, which characterizes the level of sustainable in the eight cities. By methods of cluster analysis and grey rational analysis, degree of harmony was categorized and calculated. Results revealed that harmony degree of different cities had certain gaps which were continually widening and can be divided into four categories. Relative scores on harmony of them are almost consistency with the category. It is found that the difference on land use put significant on the degree of harmony. Some other characteristics including city administrative status, comparative regional advantages also have a large impact. These findings lead further suggestions and recommendations for governments to design relevant policy.