The Royal Welsh Show

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Colours Part 1: the Regular Battalions

The Colours Part 1: The Regular Battalions By Lieutenant General J. P. Riley CB DSO PhD MA FRHistS 1. The Earliest Days At the time of the raising of Lord Herbert’s Regiment in March 1689,i it was usual for a regiment of foot to hold ten Colours. This number corre- sponded to the number of companies in the regiment and to the officers who commanded these companies although the initial establishment of Herbert’s Regiment was only eight companies. We have no record of the issue of any Colours to Herbert’s Regiment – and probably the Colo- nel paid for their manufacture himself as he did for much of the dress and equipment of his regiment. What we do know however is that each Colour was the rallying point for the company in battle and the symbol of its esprit. Colours were large – generally six feet square although no regulation on size yet existed – so that they could easily be seen in the smoke of a 17th Century battlefield for we must remember that before the days of smokeless powder, obscuration was a major factor in battle. So too was the ability of a company to keep its cohesion, deliver effec- tive fire and change formation rapidly either to attack, defend, or repel cavalry. A company was made up of anywhere between sixty and 100 men, with three officers and a varying number of sergeants, corporals and drummers depending on the actual strength. About one-third of the men by this time were armed with the pike, two-thirds with the match- lock musket. -

Xlvets Members Handbook 2016.Pdf

47383blu_Members Handbook 2015 AW 23/12/2015 15:58 Page 2 2016 Members Handbook www.xlvets.co.uk 47383blu_Members Handbook 2015 AW 23/12/2015 15:58 Page 3 47383blu_Members Handbook 2015 AW 23/12/2015 15:58 Page 4 It’s All About Getting Involved As XLVet members we believe that independent veterinary practices are the powerhouses to achieve XLVets the highest quality of service to our clients. And by working together, sharing experience, knowledge Page 04 Five Pillars for Excellence and skills, we will deliver excellence in veterinary Page 06 XLVets Members’ Mandate practice so that we are seen as experts in animal Page 08 XLVets Values health all over the world. Page 10 XLVets Strategic Plan Page 12 XLVets Business Team XLVets is an organisation of its members, for its members. Page 46 IT Services The Board of XLVets expects all of its members to actively Page 47 Email, Web Forums and Website participate within the group and to share ideas, knowledge Page 50 XLVets Member Services A - Z Guide and experience with other group members. The Board requires members to work in collaboration with other members to achieve positive outcomes. Business Management This booklet is designed to provide a summary of useful information so that you can get involved and take part with Page 14 Business Management Executive XLVets initiatives and also in order to allow you to include Page 15 Business Management Activity Plan these activities in your own practice plans for 2016. Page 17 Marketing Page 18 The Rationale for Preferred Products and Services Page 19 Using the XLVets Brandmark Page 21 Calendar 2015 XLVets members An up to date list of all XLVets member practices including an interactive google map of their locations can be found Farm on the XLVets website www.xlvets.co.uk Page 24 Farm Calendar Farm Activity Plan For further informationon any aspect of your Page 26 Farm Regional Groups XLVets membership contact the XLVets team Page 27 Farm Articles Page 29 Broomhall Buying Services Ltd on 01228 711788. -

Regimental Associations

Regimental Associations Organisation Website AGC Regimental Association www.rhqagc.com A&SH Regimental Association https://www.argylls.co.uk/regimental-family/regimental-association-3 Army Air Corps Association www.army.mod.uk/aviation/ Airborne Forces Security Fund No Website information held Army Physical Training Corps Assoc No Website information held The Black Watch Association www.theblackwatch.co.uk The Coldstream Guards Association www.rhqcoldmgds.co.uk Corps of Army Music Trust No Website information held Duke of Lancaster’ Regiment www.army.mod.uk/infantry/regiments/3477.aspx The Gordon Highlanders www.gordonhighlanders.com Grenadier Guards Association www.grengds.com Gurkha Brigade Association www.army.mod.uk/gurkhas/7544.aspx Gurkha Welfare Trust www.gwt.org.uk The Highlanders Association No Website information held Intelligence Corps Association www.army.mod.uk/intelligence/association/ Irish Guards Association No Website information held KOSB Association www.kosb.co.uk The King's Royal Hussars www.krh.org.uk The Life Guards Association No website – Contact [email protected]> The Blues And Royals Association No website. Contact through [email protected]> Home HQ the Household Cavalry No website. Contact [email protected] Household Cavalry Associations www.army.mod.uk/armoured/regiments/4622.aspx The Light Dragoons www.lightdragoons.org.uk 9th/12th Lancers www.delhispearman.org.uk The Mercian Regiment No Website information held Military Provost Staff Corps http://www.mpsca.org.uk -

W31 27/07/19 – 02/08/19

W31 27/07/19 – 02/08/19 2 Showstoppers: Best of the Royal Welsh 2019 3 Our Lives: Taking on the Irish Sea 4 Warriors: Our Homeless World Cup 5 Keeping Faith 6 Saving Britain’s Worst Zoo 7 Tudur’s TV Flashback Places of interest / Llefydd o ddiddordeb: Aberystwyth 3 Borth 6 Builth Wells / Llanelwedd 2 Llangrannog 3 New Quay / Cei Newydd 3 Port Talbot 4 Swansea / Abertawe 4 Follow @BBCWalesPress on Twitter to keep up with all the latest news from BBC Wales Dilynwch @BBCWalesPress ar Twitter i gael y newyddion diweddaraf am BBC Cymru NOTE TO EDITORS: All details correct at time of going to press, but programmes are liable to change. Please check with BBC Cymru Wales Communications on 029 2032 2115 before publishing. NODYN I OLYGYDDION: Mae’r manylion hyn yn gywir wrth fynd i’r wasg, ond mae rhaglenni yn gallu newid. Cyn cyhoeddi gwybodaeth, cysylltwch â’r Adran Gyfathrebu ar 029 2032 2115 1 SHOWSTOPPERS: BEST OF THE ROYAL WELSH 2019 Sunday, 28 July BBC One Wales, 6.05pm BBC Countryfile’s Sean Fletcher and farmer and broadcaster Gareth Wyn Jones present a special celebration of the very best moments from the biggest agricultural show in Europe – The Royal Welsh Show 2019. Looking back at the event’s one hundredth show, the pair will be joined by well-known faces who’ve been at the showground throughout the week including Keeping Faith star Eve Myles, former Welsh international Shane Williams and Carol Vorderman. They’ll also discover more about the show’s royal connections and catch up on some of the big winners in the week’s fiercely fought competitions. -

The Social Identity of Wales in Question: an Analysis of Culture, Language, and Identity in Cardiff, Bangor, and Aberystwyth

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Fulbright Grantee Projects Office of Competitive Scholarships 8-3-2012 The Social Identity of Wales in Question: An Analysis of Culture, Language, and Identity in Cardiff, Bangor, and Aberystwyth Clara Martinez Linfield College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/fulbright Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the International and Intercultural Communication Commons Recommended Citation Martinez, Clara, "The Social Identity of Wales in Question: An Analysis of Culture, Language, and Identity in Cardiff, Bangor, and Aberystwyth" (2012). Fulbright Grantee Projects. Article. Submission 4. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/fulbright/4 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Article must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Fulbright Summer Institute: Wales 2012 The Social Identity of Wales in Question: An Analysis of Culture, Language, and Identity in Cardiff, Bangor, and Aberystwyth Clara Martinez Reflective Journal Portfolio Fulbright Wales Summer Institute Professors August 3, 2012 Table of Contents Introduction -

SIRE DIRECTORY Welcome to the GENUS ABS BEEF DIRECTORY 2017 - 2018

2017 - 2018 BEEF SIRE DIRECTORY Welcome to the GENUS ABS BEEF DIRECTORY 2017 - 2018 CONTENTS SPECIALIST SYMBOLS PAGE PAGE BREED SIRE NAME BREED SIRE NAME NAME SYMBOL DEFINITION NO. NO. ANGUS Oakchurch DUSTER M109 8 SOUTH DEVON Foxhole MENZIES 41 Sire has at least Nightingale PLOUGHMAN 9 SOUTH DEVON Hawkley Poll INQUEST 41 120 calvings in 60 ROCK SOLID Netherton AMERICANO 10 SOUTH DEVON Hawkley SAS INTREPID 41 dairy herds, whose GENETICS Shadwell Jafar ERIC 11 DEVON Boskenna FERDINAND 42 performance has been ABS PROTEGE 306 12 SHORTHORN HW HAZARD 42 proven on dairy cows. Mosshall Red PHARAOH 12 WAGYU LONGFORD F E0241 42 Haymount WAR SMITH R578 12 SALER THEOREME 42 Sire has produced more BRITISH BLUE than 50,000 progeny Newpole HEARTTHROB 16 SUSSEX Friths GENERAL 42 SAPPHIRE SIRE Newpole EASY 17 to reach the acclaimed PARTHENAIS ATOMIC 43 Sapphire Sire status. Moorsley HERO 18 PARTHENAIS CAMBRIDGE 43 Greystone GOVERNOR 19 DEXTER Canwell SOOTY 43 Moorsley ANDERSON 20 LINCOLN RED Walmer PIPER 43 Sire has produced more Brookfield DEV 21 TH than 100,000 progeny WELSH BLACK Macreth BEDWYR 5 43 DIAMOND SIRE Rosemount HAL 22 to reach the legendary WELSH BLACK Tryfil CAWR 43 Redmires FREDDY 23 Diamond Sire status. MURRAY GREY Ashrose ZEBEDEE 44 Greystone JUPITER 24 BLACK GALLOWAY Blackcraig KODIAC 44 Greystone GLACIER 25 BLACK GALLOWAY Viscount of GLENTURK 44 Sire is eligible for royalty Moorsley DJ 25 BELTED GALLOWAY Cairnsmore FERGUS 44 ROYALTY fee to be paid to breeder Redmires ISAAC 25 HIGHLAND ALASDAIR 4th of Woodneuk 44 APPLICABLE or Genus ABS if progeny Rosemount IGGY 26 is registered as pedigree. -

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

Mention in Despatches Queen's Commendation for Bravery Queen's

THE LONDON GAZETTE FRIDAY 22 MARCH 2013 SUPPLEMENT No. 2 5739 Craftsman Geoffrey John Salt, Corps of Royal ROYAL AIR FORCE Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, 24870675. Corporal Kurt Lee, Royal Air Force, C8507936. MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Queen’s Commendation for Bravery Whitehall, London SW1 22 March 2013 The Queen has been graciously pleased to give orders for ARMY the publication of the names of the following as having Lance Corporal Simon David Dent, Grenadier Guards, been Mentioned in Despatches, Commended for Bravery 30068858. or Commended for Valuable Service in recognition of Private Lewis John Murphy, The Yorkshire Regiment, gallant and distinguished services in Afghanistan during 30131767. the period 1 April 2012 to 30 September 2012: Fusilier John Michael Rushton, The Royal Welsh, 30059326. Mention in Despatches Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Service ARMY Guardsman Danny Lee Bentley, Grenadier Guards, ARMY 30038982. Lance Corporal Kyle Alexanders, Intelligence Corps, Corporal Christopher Richard Brown, The King’s 25184887. Royal Hussars, 25177700. Staff Sergeant Gary Anderson, Adjutant General’s Guardsman James Robert Cornish, Grenadier Guards, Corps (Staff and Personnel Support Branch), 30055751. 24839221. Private Liam Downs, Royal Gibraltar Regiment, Lieutenant Benjamin Nigel Harrison Bardsley, Welsh GR8442. Guards, 30095044. Acting Captain Jonathan William Mortimer Hendry, Colonel John Henry Bowron, DSO OBE, late The The Parachute Regiment, 25231896. Rifles, 529717. Lance Sergeant Ashley John Hendy, Grenadier Guards, Major Charles Michael Barnard Carver, The Royal 25204996. Welsh, 548344. Sergeant Antony Craig Holland, The King’s Royal Major Andrew David Cox, MBE, The Mercian Hussars, 25093027. Regiment, 545417. Lance Corporal Adam James Jackson, The Royal Welsh, Lieutenant Jonathan Nicholas Kume-Davy, The 30034318. -

Inventory of Exchange Schemes for Young Farmers Annex II.1 to the Pilot Project: Exchange Programmes for Young Farmers

Inventory of exchange schemes for young farmers Annex II.1 to the Pilot project: Exchange programmes for young farmers Client: European Commission, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development Rotterdam, 25 September 2015 Inventory of exchange schemes for young farmers Annex II.1 to the Pilot project: Exchange programmes for young farmers Client: European Commission, Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development Marie-Jose Zondag (Ecorys Netherlands) Carolien de Lauwere (LEI-Wageningen UR) Peter Sloot (Aequator Groen & Ruimte) Andreas Pauer (Ecorys Brussels) Rotterdam, 25 September 2015 Disclaimer: The information and views set out in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. About Ecorys At Ecorys we aim to deliver real benefit to society through the work we do. We offer research, consultancy and project management, specialising in economic, social and spatial development. Focusing on complex market, policy and management issues we provide our clients in the public, private and not-for-profit sectors worldwide with a unique perspective and high-value solutions. Ecorys’ remarkable history spans more than 85 years. Our expertise covers economy and competitiveness; regions, cities and real estate; energy and water; transport and mobility; social policy, education, health and governance. We value our independence, integrity and partnerships. Our staff comprises dedicated experts from academia and consultancy, who share best practices both within our company and with our partners internationally. -

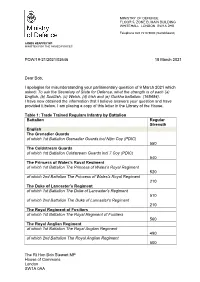

The Rt Hon Bob Stewart MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA PQW

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE FLOOR 5, ZONE B, MAIN BUILDING WHITEHALL LONDON SW1A 2HB Telephone 020 7218 9000 (Switchboard) JAMES HEAPPEY MP MINISTER FOR THE ARMED FORCES PQW/19-21/2021/02646 18 March 2021 Dear Bob, I apologise for misunderstanding your parliamentary question of 9 March 2021 which asked: To ask the Secretary of State for Defence, what the strength is of each (a) English, (b) Scottish, (c) Welsh, (d) Irish and (e) Gurkha battalion. (165484). I have now obtained the information that I believe answers your question and have provided it below. I am placing a copy of this letter in the Library of the House. Table 1: Trade Trained Regulars Infantry by Battalion Battalion Regular Strength English The Grenadier Guards of which 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards incl Nijm Coy (PDIC) 550 The Coldstream Guards of which 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards incl 7 Coy (PDIC) 540 The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment 520 of which 2nd Battalion The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment 210 The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment 510 of which 2nd Battalion The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment 210 The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers of which 1st Battalion The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers 560 The Royal Anglian Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Royal Anglian Regiment 490 of which 2nd Battalion The Royal Anglian Regiment 500 The Rt Hon Bob Stewart MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA The Yorkshire Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Yorkshire Regiment 510 -

49422 MOD Supp 1 26.05.15.Indd

MINSTRY OF DEFENCE Officer Cadet Robert Edmund THOMPSON Grenadier Guards Officer Cadet Guy Dominic HOLDER-WILLIAMS Yorkshire Regiment 30120204 from The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst to be Second 30211007 from The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst to be Second Lieutenant 11 April 2015 Lieutenant 11 April 2015 SCOTTISH DIVISION Officer Cadet Ryan Matthew LECH Yorkshire Regiment 30161383 from The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst to be Second Lieutenant REGULAR ARMY 11 April 2015 Short Service Commissions Officer Cadet George Adam STEELE Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment 30200352 from The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst to be Second Officer Cadet Thomas William CALLARD The Royal Regiment of Lieutenant 11 April 2015 Scotland 30082017 from The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst to be Second Lieutenant 11 April 2015 PRINCE OF WALES’S DIVISION Officer Cadet Guy William Mcauslane CHALK The Royal Regiment of REGULAR ARMY Scotland 30207472 from The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst to be Second Lieutenant 11 April 2015 Short Service Commissions Officer Cadet Christopher Francis GARDNER The Royal Regiment of Officer Cadet Edward Arthur IRELAND Mercian Regiment 30212050 Scotland 30139061 from The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst to be from The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst to be Second Lieutenant Second Lieutenant 11 April 2015 11 April 2015 Officer Cadet Alistair William GIBSON The Royal Regiment of Officer Cadet Matthew James IXER Royal Welsh 30138807 from Scotland 30079717 from The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst to be The Royal Military Academy -

The Great War: the Welsh Guards and the Police of South Wales

HEDDLU DE CYMRU • SOUTH WALES POLICE THE GREAT WAR: THE WELSH GUARDS AND THE POLICE OF SOUTH WALES LED BY IWM LEARN • ENGAG1 E • REMEMBER THE GREAT WAR: THE WELSH GUARDS AND THE POLICE OF SOUTH WALES Glamorgan policemen from Porthcawl who joined the Welsh Guards: Back row left to right: PC DC Grant, PC WJ Thomas and PC D Hayes. Front row sitting left PC W. Richardson, sitting right PC F Trott. Only PC’s Hayes and Richardson survived the war. 1 THE GREAT WAR: THE WELSH GUARDS AND THE POLICE OF SOUTH WALES THE GREAT WAR: THE WELSH GUARDS AND THE POLICE OF SOUTH WALES 2015 sees the centenary of the commemorative booklet for 1915 formation of the Welsh Guards in but in view of the amount of February 1915. material which we have available, As will be seen in the pages which we have produced it as a separate follow, South Wales Police’s booklet. predecessor forces of Glamorgan, We hope that it will provide a Cardiff, Swansea, Merthyr and fitting tribute to those policemen Neath had close connections with from South Wales who served the regiment from its formation. with the regiment during the First It had been our intention to World War and especially those include details of this in our who made the ultimate sacrifice. Gareth Madge OBE Chair, First World War Project Group, October 2015 2 THE GREAT WAR: THE WELSH GUARDS AND THE POLICE OF SOUTH WALES The Welsh Guards is the youngest Notwithstanding the existence of of the Foot Guards Regiments such formations, Lord Kitchener having been formed in 1915 when expressed a wish to see a it joined the Grenadier Guards, regiment of Welsh Foot Guards Coldstream Guards, Scots Guards being raised as well.