United Svc Jnl 1832-3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Colours Part 1: the Regular Battalions

The Colours Part 1: The Regular Battalions By Lieutenant General J. P. Riley CB DSO PhD MA FRHistS 1. The Earliest Days At the time of the raising of Lord Herbert’s Regiment in March 1689,i it was usual for a regiment of foot to hold ten Colours. This number corre- sponded to the number of companies in the regiment and to the officers who commanded these companies although the initial establishment of Herbert’s Regiment was only eight companies. We have no record of the issue of any Colours to Herbert’s Regiment – and probably the Colo- nel paid for their manufacture himself as he did for much of the dress and equipment of his regiment. What we do know however is that each Colour was the rallying point for the company in battle and the symbol of its esprit. Colours were large – generally six feet square although no regulation on size yet existed – so that they could easily be seen in the smoke of a 17th Century battlefield for we must remember that before the days of smokeless powder, obscuration was a major factor in battle. So too was the ability of a company to keep its cohesion, deliver effec- tive fire and change formation rapidly either to attack, defend, or repel cavalry. A company was made up of anywhere between sixty and 100 men, with three officers and a varying number of sergeants, corporals and drummers depending on the actual strength. About one-third of the men by this time were armed with the pike, two-thirds with the match- lock musket. -

The Kings Royal Rifle Corps

A B R IEF HISTORY T I ’ FL CORPS HE K NG S ROYAL RI E , 1 755 T O 1 9 1 5 . C O MP I L E D A N D E DI T E D B Y L I E UT E N A N T G E N E R A L S I R E DW A R D B UT T O N , hem-m am o the H i sto om mittee C f ry C . X C E L E R E T A UDA . L ouisber uebec 1 Martini ue 1 62 H avannah g, Q , 759 q , 7 , , " N o rth A m erica 1 6 — R o ica Vim iera Ma tini ue T a a ve a , 7 3 4 , l . , r q , l r , " " ' " " E nsa c F uentes d O nor A lbuhera C iuda d R odri o B ada oz o. , g , j , " " “ " " S alamanm “ Vittoria P nees N ive e N ive O thes T ou ouse . yre , ll , . r . l , P eninsu a Mo ltan G oo erat P unaub S outh A frica 1 8 1 —2 l . o . j . i , . 5 " " “ " “ De hi T aku F orts P ekin S outh A frica r8 A hm ad K he l , , , , 79, l, “ “ " K a nd ha A f hanista n1 8 8 T el- el- K ebi E t 1 882 a r, g , 7 r. gyp , , " " " “ — C hit a Def nc of L ad smith R i f of L a d sm ith S outh A frica 1 8 1 0 2 . -

1 Old, Unhappy, Far-Off Things a Little Learning

1 Old, Unhappy, Far-off Things A Little Learning I have not been in a battle; not near one, nor heard one from afar, nor seen the aftermath. I have questioned people who have been in battle - my father and father-in-law among them; have walked over battlefields, here in England, in Belgium, in France and in America; have often turned up small relics of the fighting - a slab of German 5.9 howitzer shell on the roadside by Polygon Wood at Ypres, a rusted anti-tank projectile in the orchard hedge at Gavrus in Normandy, left there in June 1944 by some highlander of the 2nd Argyll and Sutherlands; and have sometimes brought my more portable finds home with me (a Minie bullet from Shiloh and a shrapnel ball from Hill 60 lie among the cotton-reels in a painted papier-mache box on my drawing-room mantelpiece). I have read about battles, of course, have talked about battles, have been lectured about battles and, in the last four or five years, have watched battles in progress, or apparently in progress, on the television screen. I have seen a good deal of other, earlier battles of this century on newsreel, some of them convincingly authentic, as well as much dramatized feature film and countless static images of battle: photographs and paintings and sculpture of a varying degree of realism. But I have never been in a battle. And I grow increasingly convinced that I have very little idea of what a battle can be like. Neither of these statements and none of this experience is in the least remarkable. -

{DOWNLOAD} Sharpes Skirmish: Richard Sharpe and the Defence

SHARPES SKIRMISH: RICHARD SHARPE AND THE DEFENCE OF THE TORMES, AUGUST 1812 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bernard Cornwell | 64 pages | 03 Sep 2002 | The Sharpe Appreciation Society | 9780972222006 | English | Nottingham, United Kingdom Bernard Cornwellwhere do I start? | Originally published in Blackwood's magazine. Partially in Spain including the battles of Cuidad Rodrigo and Badajoz. Editions Londdon: S. Brereton, Captn. Brereton was a prolific author of fiction for boys, modeled after G. Brew, Margaret W. Campbell, Dr. Campbell, K. Capes, B. A Castle in Spain : being certain memoirs, thus entitled, of Robin Lois, ex-major of His Majesty's th regiment of foot Capes was a prolific late Victorian author; lately some of his ghost stories have been reprinted. Editions London: Smith, Elder. Martin's Press. Connell, F. Cornwell, Bernard Sharpe's Enemy. Amazon New York: Penguin Books. Cornwell, Bernard Sharpe's company. Cornwell, Bernard Sharpe's eagle. Cornwell, Bernard Sharpe's gold. Cornwell, Bernard Sharpe's havoc. Cornwell, Bernard Sharpe's honor. New York: Penguin Books. Cornwell, Bernard Sharpe's revenge. Cornwell, Bernard Sharpe's rifles. Cornwell, Bernard Sharpe's siege. Cornwell, Bernard Sharpe's skirmish. Revised and extended edition. Cornwell, Bernard Sharpe's sword. Crockett, S. It is included because the book is included in a short listing of fiction of the Peninsular War at Manchester Polytechnic Library. The book itself has very slight reference to the Peninsular War, but is of that time period. Editions London: Ward Lock. Dallas Alexander R. Felix Alvarez, or, Manners in Spain Containing descriptive accounts of some of the prominent events of the late Peninsular War; and authentic anecdotes illustrative of the Spanish character; interspersed with poetry, original and from the Spanish - from the title page. -

Regimental Associations

Regimental Associations Organisation Website AGC Regimental Association www.rhqagc.com A&SH Regimental Association https://www.argylls.co.uk/regimental-family/regimental-association-3 Army Air Corps Association www.army.mod.uk/aviation/ Airborne Forces Security Fund No Website information held Army Physical Training Corps Assoc No Website information held The Black Watch Association www.theblackwatch.co.uk The Coldstream Guards Association www.rhqcoldmgds.co.uk Corps of Army Music Trust No Website information held Duke of Lancaster’ Regiment www.army.mod.uk/infantry/regiments/3477.aspx The Gordon Highlanders www.gordonhighlanders.com Grenadier Guards Association www.grengds.com Gurkha Brigade Association www.army.mod.uk/gurkhas/7544.aspx Gurkha Welfare Trust www.gwt.org.uk The Highlanders Association No Website information held Intelligence Corps Association www.army.mod.uk/intelligence/association/ Irish Guards Association No Website information held KOSB Association www.kosb.co.uk The King's Royal Hussars www.krh.org.uk The Life Guards Association No website – Contact [email protected]> The Blues And Royals Association No website. Contact through [email protected]> Home HQ the Household Cavalry No website. Contact [email protected] Household Cavalry Associations www.army.mod.uk/armoured/regiments/4622.aspx The Light Dragoons www.lightdragoons.org.uk 9th/12th Lancers www.delhispearman.org.uk The Mercian Regiment No Website information held Military Provost Staff Corps http://www.mpsca.org.uk -

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 by Luke Diver, M.A

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 By Luke Diver, M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Head of Department: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisors of Research: Dr David Murphy Dr Ian Speller 2014 i Table of Contents Page No. Title page i Table of contents ii Acknowledgements iv List of maps and illustrations v List of tables in main text vii Glossary viii Maps ix Personalities of the South African War xx 'A loyal Irish soldier' xxiv Cover page: Ireland and the South African War xxv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (October - December 1899) 19 Chapter 2: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (January - March 1900) 76 Chapter 3: The ‘Irish’ Imperial Yeomanry and the battle of Lindley 109 Chapter 4: The Home Front 152 Chapter 5: Commemoration 198 Conclusion 227 Appendix 1: List of Irish units 240 Appendix 2: Irish Victoria Cross winners 243 Appendix 3: Men from Irish battalions especially mentioned from General Buller for their conspicuous gallantry in the field throughout the Tugela Operations 247 ii Appendix 4: General White’s commendations of officers and men that were Irish or who were attached to Irish units who served during the period prior and during the siege of Ladysmith 248 Appendix 5: Return of casualties which occurred in Natal, 1899-1902 249 Appendix 6: Return of casualties which occurred in the Cape, Orange River, and Transvaal Colonies, 1899-1902 250 Appendix 7: List of Irish officers and officers who were attached -

Contents the Royal Front Cover: Caption Highland Fusiliers to Come

The Journal of Contents The Royal Front Cover: caption Highland Fusiliers to come Battle Honours . 2 The Colonel of the Regiment’s Address . 3 Royal Regiment of Scotland Information Note – Issues 2-4 . 4 Editorial . 5 Calendar of Events . 6 Location of Serving Officers . 7 Location of Serving Volunteer Officers . 8 Letters to the Editor . 8 Book Reviews . 10 Obituaries . .12 Regimental Miscellany . 21 Associations and Clubs . 28 1st Battalion Notes . 31 Colour Section . 33 2006 Edition 52nd Lowland Regiment Notes . 76 Volume 30 The Army School of Bagpipe Music and Highland Drumming . 80 Editor: Army Cadet Force . 83 Major A L Mack Regimental Headquarters . 88 Assistant Editor: Regimental Recruiting Team . 89 Captain K Gurung MBE Location of Warrant Officers and Sergeants . 91 Regimental Headquarters Articles . 92 The Royal Highland Fusiliers 518 Sauchiehall Street Glasgow G2 3LW Telephone: 0141 332 5639/0961 Colonel-in-Chief HRH Prince Andrew, The Duke of York KCVO ADC Fax: 0141 353 1493 Colonel of the Regiment Major General W E B Loudon CBE E-mail: [email protected] Printed in Scotland by: Regular Units IAIN M. CROSBIE PRINTERS RHQ 518 Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow G2 3LW Beechfield Road, Willowyard Depot Infantry Training Centre Catterick Industrial Estate, Beith, Ayrshire 1st Battalion Salamanca Barracks, Cyprus, BFPO 53 KA15 1LN Editorial Matter and Illustrations: Territorial Army Units The 52nd Lowland Regiment, Walcheren Barracks, Crown Copyright 2006 122 Hotspur Street, Glasgow G20 8LQ The opinions expressed in the articles Allied Regiments Prince Alfred’s Guard (CF), PO Box 463, Port Elizabeth, of this Journal are those of the South Africa authors, and do not necessarily reflect the policy and views, official or The Royal Highland Fusiliers of Canada, Cambridge, otherwise, of the Regiment or the Ontario MoD. -

The J O U R N a L O F the M I D D L E S E X R E G I M E N T

V it e THE JOURNAL OF THE MIDDLESEX REGIMENT a nie oj- Oambriclÿe i Own) VOL. XIII No. 1 SEPTEMBER, 1957 PRICE V- THE MIDDLESEX REGIMENT (DUKE Of CAMBRIDGE'S OWN) (57th and 77th) The Plume of the Prince of Wales. In each of the four comers the late Duke of Cambridge's Cypher and Coronet. “ Mysore," “ Seringapatam,” “ Albuhera,” “ Ciudad Rodrigo," “ Badajoz,” “ Vittoria," “ Pyrenees,” “ Nivelle,” " Nive," “ Peninsular,” "A lm a,” " Inkerman,” “ Sevastopol," “ New Zealand,” “ South Africa, 1879," “ Relief of Ladysmith,” “ South Africa 1900-02." The Great War—46 Battalions—“ Mons," “ Le Cateau,” “ Retreat from Mons,” “ Marne, 1914," “ Aisne, 1914, ’i8," " La Bassée, 1914,” “ Messines, 1914, ’17, ’18,” “ Armentières, 1914," “ Neuve Chapelle,'' “ Ypres, 1915, ’17, ’18," “ GravenstafeL,” “ St. Julien,” “ Frezenberg,” “ Bellewaarde, ’ “ Aubers,” “ Hooge, 1915,” “ Loos," “ Somme," 1916, ’18,” "Albert, 1916, ’18,” “ Bazentin,” " Delville Wood,” “ Pozières,” “ Ginchy,” “ Flers-Courcelette,” “ Morval,” " Thiepval,” “ Le Transloy,” “ Ancre Heights,” " Ancre, 1916, ’iS,” " Bapaume, 1917, ’18,” “ Arras, 1917, ’18,” “ Vimy, 1917,” “ Scarpe, 1917, ’i8,” “ Arleux,” " Pilckem,” “ Langemarck, 1917,” “ Memn Road,” ‘‘Polygon Wood,” “ Broodseinde," “ Poelcappelle,” “ Passchendaele,” " Cambrai, 1917, ’18,” "St. Quentin,” “ Rosières,” “ Avre,” “ Villers Bretonneux,” “ Lys,” “ Estaires,” “ Hazebrouck,” " Bailleul,” “ Kemmel," “ Scherpenberg," “ Hindenburg Line,” “ Canal du Nord,” “ St. Quentin Canal,” “ Courtrai,” “ Selle,” “ Valenciennes,” “ Sambre,” “ France and Flanders, 1914-18,” “ Italy, 1917-18,” “ Struma," “ Doiran, 1918,” “ Macedonia, 1915-18,” “ Suvla," “ Landing at Suvla,” “ Scimitar Hül,” “ Gallipoli, 1915." “ Rumani,” “ Egypt, 1915-17,” “ Gaza,” “ El Mughar,” “ Jerusalem," “ Jericho,” "Jo rd an ,” “ Tell ’Asur,” “ Palestine 1917-18,” “ Mesopotamia, 1917-18,” “ Murman ,1919.” “ Dukhovskaya,” “ Siberia, 1918-19.” Regular Battalion Dominion and Colonial Alliance 1st Bn. (Amalgamated with 2nd Bn. 1948). C a n a d a . -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 28Th July 1964 6399

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 28TH JULY 1964 6399 FUSILIER BRIGADE HIGHLAND BRIGADE R. War. F. Camerons REGULAR ARMY TERRITORIAL ARMY Lt. M. ROSS-THOMAS (459314) to be Capt, 27th Lt. R. J. AITKEN (465654) to be Capt., 4th July July 1964. 1964. Lt. J. M. G. GRANT (454304) is granted the actg. R.F. rank of Capt., 4th July 1964. REGULAR ARMY Short Serv. Commn. PARACHUTE REGIMENT 14482058 W.O. Cl. 1 William George PETTIFAR TERRITORIAL ARMY RESERVE OF OFFICERS (476978) to be Lt. (Q.M.), 26th June 1964. Maj. C. A. AMOORE (140048) having attained the age limit, ceases to belong to the T.A. Res. L.F. of Offrs. 28th July 1964, retaining the rank of Maj. TERRITORIAL ARMY Maj. K. M. WALTON (425740) is placed on the BRIGADE OF GURKHAS Unatt'd List, 1st June 1964. 6 G.R. REGULAR ARMY EAST ANGLIAN BRIGADE The undermentioned to be Lts. (Q.G.O.) on the dates shown: S.C. 21145200 C/Sgt. BHADRE BURA (477051), 23rd TERRITORIAL ARMY RESERVE OF OFFICERS Apr. 1964. Capt. (Hon. Maj.) P. F. RODWELL, M.B.E., T.D. 21136418 C/Sgt. TEKBAHADUR GURUNO (477052), (51377) having attained the age limit, ceases to 24th Apr. 1964. belong to the T.A. Res. of Offrs., 28th July 1964, 21136915 W.O. Cl. I BIRKHARAJ GURUNG retaining the hon. rank of Maj. (477053), 25th Apr. 1964. 21136329 W.O. C3. II GAMBAHADUR GURUNG 2 E. Anglian (477048), 14th Apr. 1964. REGULAR ARMY 21143478 W.O'. Cl. IT NARDHOJ THAPA (477049), 2nd Lt. N. T. -

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

Mention in Despatches Queen's Commendation for Bravery Queen's

THE LONDON GAZETTE FRIDAY 22 MARCH 2013 SUPPLEMENT No. 2 5739 Craftsman Geoffrey John Salt, Corps of Royal ROYAL AIR FORCE Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, 24870675. Corporal Kurt Lee, Royal Air Force, C8507936. MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Queen’s Commendation for Bravery Whitehall, London SW1 22 March 2013 The Queen has been graciously pleased to give orders for ARMY the publication of the names of the following as having Lance Corporal Simon David Dent, Grenadier Guards, been Mentioned in Despatches, Commended for Bravery 30068858. or Commended for Valuable Service in recognition of Private Lewis John Murphy, The Yorkshire Regiment, gallant and distinguished services in Afghanistan during 30131767. the period 1 April 2012 to 30 September 2012: Fusilier John Michael Rushton, The Royal Welsh, 30059326. Mention in Despatches Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Service ARMY Guardsman Danny Lee Bentley, Grenadier Guards, ARMY 30038982. Lance Corporal Kyle Alexanders, Intelligence Corps, Corporal Christopher Richard Brown, The King’s 25184887. Royal Hussars, 25177700. Staff Sergeant Gary Anderson, Adjutant General’s Guardsman James Robert Cornish, Grenadier Guards, Corps (Staff and Personnel Support Branch), 30055751. 24839221. Private Liam Downs, Royal Gibraltar Regiment, Lieutenant Benjamin Nigel Harrison Bardsley, Welsh GR8442. Guards, 30095044. Acting Captain Jonathan William Mortimer Hendry, Colonel John Henry Bowron, DSO OBE, late The The Parachute Regiment, 25231896. Rifles, 529717. Lance Sergeant Ashley John Hendy, Grenadier Guards, Major Charles Michael Barnard Carver, The Royal 25204996. Welsh, 548344. Sergeant Antony Craig Holland, The King’s Royal Major Andrew David Cox, MBE, The Mercian Hussars, 25093027. Regiment, 545417. Lance Corporal Adam James Jackson, The Royal Welsh, Lieutenant Jonathan Nicholas Kume-Davy, The 30034318. -

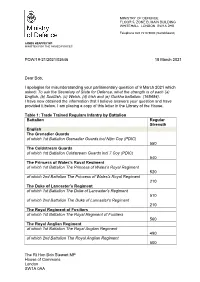

The Rt Hon Bob Stewart MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA PQW

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE FLOOR 5, ZONE B, MAIN BUILDING WHITEHALL LONDON SW1A 2HB Telephone 020 7218 9000 (Switchboard) JAMES HEAPPEY MP MINISTER FOR THE ARMED FORCES PQW/19-21/2021/02646 18 March 2021 Dear Bob, I apologise for misunderstanding your parliamentary question of 9 March 2021 which asked: To ask the Secretary of State for Defence, what the strength is of each (a) English, (b) Scottish, (c) Welsh, (d) Irish and (e) Gurkha battalion. (165484). I have now obtained the information that I believe answers your question and have provided it below. I am placing a copy of this letter in the Library of the House. Table 1: Trade Trained Regulars Infantry by Battalion Battalion Regular Strength English The Grenadier Guards of which 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards incl Nijm Coy (PDIC) 550 The Coldstream Guards of which 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards incl 7 Coy (PDIC) 540 The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment 520 of which 2nd Battalion The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment 210 The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment 510 of which 2nd Battalion The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment 210 The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers of which 1st Battalion The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers 560 The Royal Anglian Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Royal Anglian Regiment 490 of which 2nd Battalion The Royal Anglian Regiment 500 The Rt Hon Bob Stewart MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA The Yorkshire Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Yorkshire Regiment 510