Knowledge and Subjectivity in Maritain, Stravinsky, and Messiaen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IGOR STRAVINSKY Symphony of Psalms

IGOR STRAVINSKY Symphony of Psalms BORN: June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum (now Lomonosov), Saint Petersburg, Russia DIED: April 6, 1971, in New York City WORK COMPOSED: 1930 WORLD PREMIERE: December 13, 1930, at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, Belgium; Société Philharmonique de Bruxelles, Ernest Ansermet conducting The latter years of the 1920s were an emotionally trying time for Stravinsky. He was carrying on an open affair with his mistress in Paris while his wife Katya was in the south of France dying of tuberculosis. (Katya was Stravinsky’s cousin, they married in 1906. She was diagnosed with the disease in 1914 after the birth of their fourth child and was confined to a sanatorium in the Alps where she died in March 1939.) He also was finding little success with his works from this time. Vivid musical evocations of disease, deterioration, debilitation, decay and denial abound in his 1927 work Oedipus Rex, which was a failure at its premiere in Paris. Serge Koussevitzky, Stravinsky’s publisher and conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (also a virtuoso double bassist!), made a suggestion to Stravinsky that he should write something popular in order to have a success. The thought was for Stravinsky to write something the people could understand. However, Stravinsky thought it should be about something universally admired; he felt that society had lost the ability to share a sacred experience. Stravinsky was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church during most of his life. No doubt that this inspired him to compose the Symphony of Psalms. Even though it is a large choral piece, he called it a symphony to appease Koussevitzky because the request was for an orchestral work. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Mengjiao Yan Phd Thesis.Pdf

The University of Sheffield Stravinsky’s piano works from three distinct periods: aspects of performance and latitude of interpretation Mengjiao Yan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music The University of Sheffield Jessop Building, Sheffield, S3 7RD, UK September 2019 1 Abstract This research project focuses on the piano works of Igor Stravinsky. This performance- orientated approach and analysis aims to offer useful insights into how to interpret and make informed decisions regarding his piano music. The focus is on three piano works: Piano Sonata in F-Sharp Minor (1904), Serenade in A (1925), Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1958–59). It identifies the key factors which influenced his works and his compositional process. The aims are to provide an informed approach to his piano works, which are generally considered difficult and challenging pieces to perform convincingly. In this way, it is possible to offer insights which could help performers fully understand his works and apply this knowledge to performance. The study also explores aspects of latitude in interpreting his works and how to approach the notated scores. The methods used in the study include document analysis, analysis of music score, recording and interview data. The interview participants were carefully selected professional pianists who are considered experts in their field and, therefore, authorities on Stravinsky's piano works. The findings of the results reveal the complex and multi-faceted nature of Stravinsky’s piano music. The research highlights both the intrinsic differences in the stylistic features of the three pieces, as well as similarities and differences regarding Stravinsky’s compositional approach. -

MTO 13.1: Francis, Review of Carr

Volume 13, Number 1, March 2007 Copyright © 2007 Society for Music Theory Kimberly A. Francis KEYWORDS: Igor Stravinsky, sketch studies, neo-classicism, Greek, Apollo Musagète, Oedipus Rex, Perséphone, Orpheus ABSTRACT: Igor Stravinsky composed four neo-classical dramatic works based on Greek subjects between 1926 and 1948. Maureen Carr explores the philosophical tenets behind his neo-classical aesthetic, especially the commonplace metaphor of the mask, and what this reveals about Stravinsky’s compositional ethos. After establishing this framework, she examines both the compositional and collaborative processes involved in the creation of these four works, drawing on extensive sketch studies and primary sources. Received February 2007 [1] In 1926, Igor Stravinsky began work on the first of what would become four works on subjects from Classical Greek literature, his opera-oratorio Oedipus Rex. In the following two decades, he completed Apollo Musagète (1927–28), Perséphone (1933–34), and Orpheus (1947–48). All four of these staged works lie squarely within Stravinsky’s neoclassical period, and each offers particular insight into the myriad elements that define this segment of Stravinsky’s oeuvre. In Multiple Masks: Neoclassicism in Stravinsky’s Works on Greek Subjects, Maureen Carr addresses the compositional processes involved in the creation of these pieces, drawing extensively from the respective drafts and sketches owned by the Paul Sacher Stiftung and the Library of Congress. Aligning her sketch studies with excerpts from diaries, letters, and other primary sources, Carr interrogates the philosophical underpinnings of Stravinsky’s neoclassical endeavors and questions the composer’s own statements about his compositional processes. In particular, Carr concerns herself with the metaphor of the “mask” and how it is central to the rhetoric of the neoclassical period, used both to herald a new artistic ethos and to sublimate Stravinsky’s own individualism and compositional techniques. -

Plays of Sophocles

E A TEACHER’S GuidE TO THE SiGNET CLASSiCS EDITiON OF SOPHOCLES: THE COMPLETE PLAYS by Laura reis Mayer SerieS editorS: Jeanne M. McGlinn and JaMeS e. McGlinn TEACHER’S Guid 2 A Teacher’s Guide to the Signet Classics Edition of Sophocles: The Complete Plays TabLe of ConTenTs introduction ........................................................................................................................3 list of characters .............................................................................................................3 SynopSiS of the oEdipuS triloGy ..............................................................................4 prereadinG activiTies .......................................................................................................5 DURING READING ACTIVITiES..........................................................................................10 AfTER READING ACTIVITiES .............................................................................................14 ABOUT THE AuTHoR OF THiS GUIDE ...........................................................................19 ABOUT THE EDIToRS OF THiS GUIDE ...........................................................................19 Copyright © 2010 by Penguin Group (USa) For additional teacher’s manuals, catalogs, or descriptive brochures, please email [email protected] or write to: PenGUin GroUP (USa) inC. in Canada, write to: academic Marketing department PenGUin BooKS CANADA LTD. 375 Hudson Street academic Sales new York, nY 10014-3657 90 eglinton -

Notes on the Oedipus Works

Notes on the Oedipus Works Matthew Aucoin The Orphic Moment a dramatic cantata for high voice (countertenor or mezzo-soprano), solo violin, and chamber ensemble (15 players) The story of Orpheus is music’s founding myth, its primal self-justification and self-glorification. On Orpheus’s wedding day, his wife, Eurydice, is fatally bitten by a poisonous snake. Orpheus audaciously storms the gates of Hell to plead his case, in song, to Hades and his infernal gang. The guardians of death melt at his music’s touch. They grant Eurydice a second chance at life: she may follow Orpheus back to Earth, on the one condition that he not turn to look at her until they’re above ground. Orpheus can’t resist his urge to glance back; he turns, and Eurydice vanishes. The Orpheus myth is typically understood as a tragedy of human impatience: even when a loved one’s life is at stake, the best, most heroic intentions are helpless to resist a sudden instinctive impulse. But that’s not my understanding of the story. Orpheus, after all, is the ultimate aesthete: he’s the world’s greatest singer, and he knows that heartbreak and loss are music’s favorite subjects. In most operas based on the Orpheus story – and there are many – the action typically runs as follows: Orpheus loses Eurydice; he laments her loss gorgeously and extravagantly; he descends to the underworld; he gorgeously and extravagantly begs to get Eurydice back; he is granted her again and promptly loses her again; he laments even more gorgeously and extravagantly than before. -

Download Program Notes

L’Oiseau de feu (The Firebird) (complete ballet score) Igor Stravinsky s musicians go, Igor Stravinsky was a Nightingale (1914), Pulcinella (1920), Mavra A rather late bloomer. He didn’t begin pia- (1922), Reynard (1922), The Wedding (1923), no lessons until he was nine, but these were Oedipus Rex (1927), and Apollo (1928). soon supplemented by private tutoring in The Ballets Russes made a specialty of harmony and counterpoint. His parents sup- pieces inspired by Russian folklore (pri- ported his musical inclinations, all the more meval Russian history being a cultural ob- laudable since they knew what their teenag- session of the moment) and The Firebird er was getting into. (Stravinsky’s father was a was perfectly suited to the company’s de- bass singer at the opera houses of Kiev and, signs. The tale involves the dashing Prince later, St. Petersburg; his mother was an accom- Ivan (Ivan Tsarevich), who finds himself plished amateur pianist.) One of Stravinsky’s one night wandering through the garden friends at school was the son of the celebrat- of King Kashchei, an evil monarch whose ed composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. When power resides in a magic egg that he guards Stravinsky’s father died, in December 1902, in an elegant box. In Kashchei’s garden, the Rimsky-Korsakov became a mentor, both per- Prince captures a Firebird, which pleads sonal and musical, to the aspiring composer. for its life. The Prince agrees to spare it if By 1907 Stravinsky (already 25 years old) was it gives him one of its magic tail feathers, ready to bestow an opus number on one of his which it consents to do. -

Download Program Notes

Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) Igor Stravinsky gor Stravinsky, son of an esteemed bass elegant (and remains so), although its decora - I singer at St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky The - tive appointments were very up-to-date in atre, received a firm grounding in composi - 1913, enough to alarm a public accustomed to tion from Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, with imbibing culture in neo-Renaissance sur - whom he studied from 1902 until Rimsky- roundings. The theater’s initial bout of pro - Korsakov’s death, in 1908. He achieved sev - gramming was far from scurrilous (though the eral notable works during those student mid-May premiere of Debussy’s Jeux caused years, but his breakthrough to fame arrived anxiety through its suggestions of a ménage à when he embarked on a string of collabora - trois ). When the spring season concluded with tions with the ballet impresario Sergei Dia- the “saison russe” of opera and ballet, Dia- ghilev, whose Ballets Russes, launched in ghilev’s productions alternated with the pre - Paris in 1909, became quickly identified with miere performances of Gabriel Fauré’s opera the cutting edge of the European arts scene. Pénélope , on a double-bill with a ballet setting Stravinsky’s first Diaghilev project was of Debussy’s Nocturnes , both of which tem - modest: a pair of Chopin orchestrations for the pered their adventurous ideas with an over - 1909 production of Les Sylphides . The produc - riding lyricism. tion was a success, although some critics com - By May 29 the audience was ready to let plained that the troupe’s choreographic and loose, and it had been prepared to do so by scenic novelty was not matched by its conser - advance press reports that not only ensured a vative musical selection. -

Theory of Music-Stravinsky

Theory of Music – Jonathan Dimond Stravinsky (version October 2009) Introduction Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was one of the most internationally- acclaimed composer conductors of the 20th Century. Like Bartok, his compositional style drew from the country of his heritage – Russia, in his case. Both composers went on to spend time in the USA later in their careers also, mostly due to the advent of WWII. Both composers were also exposed to folk melodies early in their lives, and in the case of Stravinsky, his father sang in Operas. Stravinsky’s work influenced Bartok’s – as it tended to influence so many composers working in the genre of ballet. In fact, Stravinsky’s influence was so broad that Time Magazine named him one of th the most influential people of the 20 Century! http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Igor_Stravinsky More interesting, however, is the correlation of Stravinsky’s life with that of Schoenberg, who were contemporaries of each other, yet had sometimes similar and sometimes contradictory approaches to music. The study of their musical output is illuminated by their personal lives and philosophies, about which much has been written. For such writings on Stravinsky, we have volumes of work created by his long-term companion and assistant, the conductor/musicologist Robert Craft. {See the Bibliography.} Periods Stravinsky’s compositions fall into three distinct periods. Some representative works are listed here also: The Dramatic Russian Period (1906-1917) The Firebird (1910, revised 1919 and 1945) Petrouchka (1911, revised 1947)) -

Oedipus Rex with Symphony of Psalms

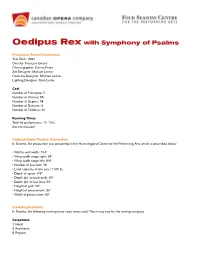

Oedipus Rex with Symphony of Psalms Production Rental Information Year Built: 1997 Director: François Girard Choreographer: Donna Feore Set Designer: Michael Levine Costume Designer: Michael Levine Lighting Designer: Alain Lortie Cast Number of Principals: 7 Number of Chorus: 55 Number of Supers: 78 Number of Dancers: 5 Number of Children: 10 Running Times Total for performance: 1h 12m (no intermission) Original/Home Theatre Information In Toronto, the production was presented in the Hummingbird Centre for the Performing Arts which is described below: • Wall to wall width: 104’ • Wing width stage right: 24’ • Wing width stage left: N/A • Number of line sets: 79 • Load capacity of line sets: 1100 lb. • Depth of apron: 4’6” • Depth (p.l. to back wall): 60’ • Depth (p.l. to last line): 50’ • Height of grid: 72’ • Height of proscenium: 30’ • Width of proscenium: 60’ Crew Requirements In Toronto, the following running crew sizes were used. These may vary for the renting company. Carpenters 1 Head 2 Assistants 8 Regular Electricians 2 Heads 2 Assistants 3 Regular 6 Special Operators Props 1 Head 4 Regular Wardrobe 1 Head 1 Assistant 14 Regular Wigs & Make-up 14 Set/Technical Information • Number and size of trucks: 3 x 48’ • Film/video effects. • Flame effect; smoke throughout. • Body mic (The Speaker). Properties Information Properties are available with rental. Costume Information Costumes are available with rental. Principal Costumes: 6 Male 1 Female Chorus Costumes: 35 Male 20 Female Supers Costumes: 33 Male 36 Female Dancers Costumes: 0 Male 5 Female Children’s Costumes: 5 Male 4 Female Wig & Make-up Information • Partial to full body make-up “mud” and “ash” for all supers. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 59,1939-1940, Trip

[Harvard University'} '% *m BOSTON symphony orchestra FOUNDED IN 1881 BY HENRY L. HIGGINSON FIFTY-NINTH SEASON 1939-1940 [7] Thursday Evening, March 28 at 8 o'clock BERKSHIRE SYMPHONIC FESTIVAL OF 1940 at "Tanglewood" (Between Stockbridge and Lenox, Mass.) Boston^ Symphony Orchestras SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Nine Concerts on Thursday and Saturday Eves., and Sunday Afts. Series A: August 1, 3, 4 The First Symphonies of Beethoven, Schumann and Sibelius. The C major Symphony of Schubert, the Second Sym- phony of Brahms, and the Third of Roy Harris. Other works include Bach's Passacaglia (orchestrated by Respighi), Faure's Suite "Pelleas et Melisande," Stravinsky's "Capriccio" (Soloist J. M. Sanroma, Piano), Prokofieff's "Classical" Symphony, and Ravel's "Daphnis et Chloe" (Second Suite). Series B: August 8, 10, 11 A TCHAIKOVSKY FESTIVAL (Celebrating the 100th anniversary of the composer's birth) The Second, Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Symphonies. The Violin Concerto (Albert Spalding, Soloist). The Overture "Romeo and Juliet," Serenade for Strings, Second Suite and other works to be announced. Artur Rodzinski will conduct one of the three programmes. Series C: August 15, 17, 18 The Third ("Eroica") Symphony of Beethoven, the First of Brahms, and a Symphony of Haydn. Other works include Wagner excerpts, Hindemith's "Mathis der Maler," arias by Dorothy Maynor and BACH'S MASS IN B MINOR with the Festival Chorus of the Berkshire Music Center and Soloists to be announced Subscription blanks may be secured by applying to the Berkshire Symphonic Festival, Inc., Stockbridge, Mass. §>atttorfi 3Itf?atr£ • Harvard University • (Eatttbrtftg? FIFTY-NINTH SEASON, 1939-1940 Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Richard Burgin, Assistant Conductor Concert Bulletin of the Seventh Concert THURSDAY EVENING, March 28 with historical and descriptive notes by John N.