Internet Companies in Japan After the Collapse of the Internet Bubble -An Analysis of Internet Companies and Their Cluster-

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

210419 Testimony of Tareq Amin FINAL

Testimony of Tareq Amin Representative Director, Executive Vice President and CTO of Rakuten Mobile Hearing on “Leading the Wireless Future: Securing American Network Technology” U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce, Subcommittee on Communications and Technology April 21, 2021 Good morning, Chairmen Pallone and Doyle, Ranking Members McMorris Rodgers and Latta, and Members of the Subcommittee. Thank you for the opportunity to testify today on this important topic. I am Tareq Amin, Representative Director, Executive Vice President and CTO of Rakuten Mobile. To start, let me say Rakuten doesn’t think of itself as a mobile operator. We are a technology company, with both Japanese and American DNA, committed to bringing the best of what the technology sector offers to advance the agility, security, and affordability of the wireless networks and services. In fact, Rakuten Mobile is its own first customer. Running on our open cloud-based Rakuten Communications Platform (or RCP), our mobile network in Japan proves that cloud-based wireless networks are no longer a vision that merits discussion. They are not just a proof of concept, they are a reality. We are driving a more diverse supply chain, with continuing innovation across multiple technologies, and providing significant consumer benefit. And, the majority of our network components come from U.S. suppliers. In today’s testimony I want to help you see through my eyes and those of our employees, executives, and customers how we decided to revolutionize mobile and wireless networks and the advantages of such an architecture for American networks. Almost seven years ago, I had an opportunity to visit the data centers of one of America’s top Internet platforms and I was shocked to see how they engineered, how they built, and how they architected their systems. -

Factset-Top Ten-0521.Xlsm

Pax International Sustainable Economy Fund USD 7/31/2021 Port. Ending Market Value Portfolio Weight ASML Holding NV 34,391,879.94 4.3 Roche Holding Ltd 28,162,840.25 3.5 Novo Nordisk A/S Class B 17,719,993.74 2.2 SAP SE 17,154,858.23 2.1 AstraZeneca PLC 15,759,939.73 2.0 Unilever PLC 13,234,315.16 1.7 Commonwealth Bank of Australia 13,046,820.57 1.6 L'Oreal SA 10,415,009.32 1.3 Schneider Electric SE 10,269,506.68 1.3 GlaxoSmithKline plc 9,942,271.59 1.2 Allianz SE 9,890,811.85 1.2 Hong Kong Exchanges & Clearing Ltd. 9,477,680.83 1.2 Lonza Group AG 9,369,993.95 1.2 RELX PLC 9,269,729.12 1.2 BNP Paribas SA Class A 8,824,299.39 1.1 Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. 8,557,780.88 1.1 Air Liquide SA 8,445,618.28 1.1 KDDI Corporation 7,560,223.63 0.9 Recruit Holdings Co., Ltd. 7,424,282.72 0.9 HOYA CORPORATION 7,295,471.27 0.9 ABB Ltd. 7,293,350.84 0.9 BASF SE 7,257,816.71 0.9 Tokyo Electron Ltd. 7,049,583.59 0.9 Munich Reinsurance Company 7,019,776.96 0.9 ASSA ABLOY AB Class B 6,982,707.69 0.9 Vestas Wind Systems A/S 6,965,518.08 0.9 Merck KGaA 6,868,081.50 0.9 Iberdrola SA 6,581,084.07 0.8 Compagnie Generale des Etablissements Michelin SCA 6,555,056.14 0.8 Straumann Holding AG 6,480,282.66 0.8 Atlas Copco AB Class B 6,194,910.19 0.8 Deutsche Boerse AG 6,186,305.10 0.8 UPM-Kymmene Oyj 5,956,283.07 0.7 Deutsche Post AG 5,851,177.11 0.7 Enel SpA 5,808,234.13 0.7 AXA SA 5,790,969.55 0.7 Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Japanese E-Commerce Contract Software & Comp Services

Boku New contract Japanese e-commerce contract Software & Comp Services 26 September 2018 Boku has widened its reach in the domestic Japanese market through a new agreement to provide direct carrier billing (DCB) services to a Rakuten Price 172.0p e-commerce business. The contract is significant in that it demonstrates Market cap £369m Boku’s ability to support physical as well as digital goods, as well as for its potential to be expanded to support additional Rakuten services. Net cash ($m) at end H118 28.4 Shares in issue 214.2m Revenue EBITDA* EPS* DPS P/E EV/EBITDA Year end ($m) ($m) ($) ($) (x) (x) Free float 45.4% 12/17 24.4 (2.3) (0.03) 0.0 N/A N/A Code BOKU 12/18e 34.8 5.4 0.01 0.0 207.4 85.4 12/19e 42.0 11.6 0.03 0.0 68.9 39.8 Primary exchange AIM 12/20e 49.9 19.1 0.06 0.0 37.4 24.2 Secondary exchange N/A Note: *EBITDA and EPS (diluted) are normalised, excluding amortisation of acquired intangibles, exceptional items and share-based payments. Share price performance Boku has signed an initial deal to provide direct carrier billing for Rakuten Collection, an e-commerce site focused on limited edition, collectibles trading in Japan, and a division of Rakuten Group (Tokyo listed, market cap ¥1.2tn/£8.3bn). This represents Boku’s first major agreement for physical e-commerce in Japan. We note that the Rakuten Group operates more than 70 services, including an e- commerce shopping mall (Rakuten Ichiba), streaming video (Rakuten TV) and e- books (Rakuten Kobo). -

Impact of COVID-19 on Consumer Behaviour

Impact of COVID-19 on Consumer Behaviour April 2020 Our Proprietary Panels Japan (JP) China (CN) South Korea (KR) 2,200,000 3,204,500 640,000 Taiwan (TW) Hong Kong (HK) Singapore (SG) 120,000 52,000 80,000 Thailand (TH) Malaysia (MY) Indonesia (ID) 550,000 196,000 550,000 India (IN) Vietnam (VN) Philippines (PH) 650,000 300,000 315,000 • Markets: China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Survey Thailand, United States, Vietnam Methodology & Sample size: 1,000 respondents per market, 13,000 in total Notes • • Profile of respondents: 20+ y.o. respondents from Rakuten Insight proprietary panels, with good distribution on age, gender, region & occupation • Survey timing April 2020 Sources of information News on traditional forms of media, TV, radio Marked contrast between Japan & China when it comes to continues to be a highly trusted source of trusting experts & influencers on social media with trust information even in the digital age much higher in China & lower in Japan Korea relatively low trust in many sources of While people spend more time watching TV news or information with the most highly trusted reading news websites, the time spent on following source being TV news (71%) influencers or celebrities on social media is less than usual Consumers from around the world rely on These times of uncertainty & gravity appear to have led to information from TV news & government consumers to spend their time on more serious & reliable websites. A slight decrease can be observed in sources of information trusting the information on social media How much do you trust the following sources of information? International consumers rely on information from Government websites and TV news. -

Japan Corporate Credit Spotlight

Makiko Yoshimura Japan Corporate Director Corporate Ratings Credit Spotlight Katsuyuki Nakai Director October 22, 2020 Corporate Ratings Hiroki Shibata Senior Director Corporate Ratings Advertising; Electronics; IT Services; E-Commerce; Telecom And Investment Holding Companies This report does not constitute a rating action. Japan Corporate Credit Spotlight Sector Comments Pages 3 - 13 Advertising Electronics Appendix IT Services Pages 14 - 16 E-Commerce Telecom And Investment Holding Companies All graphics show data for companies studied. Sector Comments Pages 3 - 13 Advertising Outlook: Negative Gradual Recovery After Temporary COVID-19 Hit Trend And Changes – Advertising revenue, which is vulnerable to economic downturns, will contract more sharply than Japan's GDP during the COVID-19 pandemic. – Digital media will likely lead a recovery thanks to cost advantages and demand for marketing data. – Companies in this study are among domestic leaders in digital advertising and media. – Competitive differences among Japan-based and overseas advertisers will not change significantly as all face similar conditions. – Future creditworthiness of the companies studied largely hinges on their financial standings. Key Assumptions – Total advertising revenue in Japan in fiscal 2021 will not recover to fiscal 2019 levels, despite the contribution from internet advertising. – Profitability of the companies studied will not recover to pre-COVID-19 levels in the coming one to two years despite cost reductions. – COVID-19's degree of impact on the companies studied will differ according to their financial health before the crisis. 4 Advertising Risks And Key Credit Drivers: – A resurgence of COVID-19 further souring advertising clients' appetites. – Priorities for use of cash flow, such as growth investments and shareholder returns, under difficult conditions. -

Strong in the New Normal 2.0

Strong in the New Normal 2.0 CORPORATE REPORT 2020 MISSION Contribute to society by creating value through innovation and entrepreneurship Our Philosophy Empowering people to realize their hopes and dreams. Embracing new thinking. The Rakuten Group’s mission is to contribute Rakuten changes the world through innovation. to society by creating value through innova- tion and entrepreneurship. By providing high-quality services that help our users and partners grow, we aim to VISION advance and enrich society. To fulfill our role as a Global Innovation Global Innovation Company Company, we are committed to maximizing both corporate and shareholder value. At Rakuten, we drive disruptive innovation, engaging knowledge, creativity and passion from around the world to achieve ambitious goals, and help build communities in which people can pursue their dreams and live in happiness. VALUES AND PRINCIPLES Rakuten Shugi (Rakuten Basic Principles) The core values of the Rakuten Group, along with the values and principles understood and practiced by Rakuten employees, embody Rakuten Shugi. The two components it consists of are the Brand Concepts and Five Principles for Success. With Rakuten Shugi as a common foundation, we place high value on the entrepreneurial spirit that drives us to get things done. By working with local communities and nurturing a robust corporate culture enabling each member of our diverse team to perform at their best, the Rakuten Group is committed to boosting corporate value and contributing to progress in society. 2 Rakuten Group, Inc. Corporate Report 2020 Contents Introduction 2 Business Strategies for Further Growth 24 Rakuten’s Governance 47 A Massive Expansion of Rakuten Ecosystem Amidst a Core Businesses 1 Conversation Once-in-a-century Digital Transformation of Society 2 E-commerce services show strong growth alongside Sarah J. -

Cebit2017 Japan Pavilion List of Exhibitors As of 25Th Jan 2017 JETRO Trade Fair Department

CeBIT2017 Japan Pavilion List of exhibitors as of 25th Jan 2017 JETRO Trade Fair Department *alphabetical order by zone Zone Name of Exhibitors URL 1 Life/Office/Society ABEJA, Inc. http://www.abeja.asia/ 2 Life/Office/Society Afro Co., Ltd. https://www.afro.co.jp 3 Life/Office/Society AISIN SEIKI Co., Ltd. http://www.aisin.com 4 Life/Office/Society Asahi Kasei Corp. http://www.asahi-kasei.co.jp/asahi/en/ 5 Life/Office/Society Asterisk, Inc. https://asreader.com/ 6 Life/Office/Society Broadband Tower, Inc. http://www.bbtower.co.jp/en/corporate/ 7 Life/Office/Society Canon Inc. http://global.canon/en/ 8 Life/Office/Society CEATEC JAPAN http://www.ceatec.com/ 9 Life/Office/Society CENOTE Inc. http://cenote.tech 10 Life/Office/Society Cerevo Inc. http://cerevo.com 11 Life/Office/Society Classmethod https://classmethod.jp/company/english/ 12 Life/Office/Society Craftar Inc. http://www.craftar.co.jp/ 13 Life/Office/Society CS-COMMUNICATION Co.,Ltd. http://www.cs-com.co.jp/ 14 Life/Office/Society Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd. http://www.dnp.co.jp/eng 15 Life/Office/Society Data Stadium Inc. https://www.datastadium.co.jp/en/index 16 Life/Office/Society DENSO CORPORATION https://www.denso.com/global/en/ 17 Life/Office/Society Design M Plus, Inc. http://www.design-mplus.com/en 18 Life/Office/Society Dynamic Map Planning Co., Ltd http://dynamic-maps.co.jp 19 Life/Office/Society Epson Europe B.V. http://global.epson.com/ 20 Life/Office/Society Falcon Denshi K.K. http://www.falcon-denshi.co.jp/en/index.shtml 21 Life/Office/Society Forum8 Co., Ltd. -

Announcement of Issuance of New Shares and Disposal of Treasury Stock Through Third-Party Allotment

March 12, 2021 Company name Rakuten, Inc. Representative Hiroshi Mikitani Chairman and CEO (Stock Code: 4755 Tokyo Stock Exchange First Section) Announcement of Issuance of New Shares and Disposal of Treasury Stock through Third-Party Allotment At a Board of Directors meeting held today, Rakuten, Inc., (hereinafter “the Company”), resolved to issue new shares and dispose of treasury stock through third-party allotment (hereinafter the “Third-Party Allotment”), as described below. 1. Details of Offering (1) Payment date From March 29, 2021 to April 30, 2021 (2) Number of new shares to be issued and Total number of common shares as below (1+2): 211,656,500 shares Number of treasury 1. Number of newly issued common shares: 139,737,600 shares stock to be disposed 2. Number of disposed treasury stocks: 71,918,900 shares of (Number of shares offered) (3) Issue price and JPY 1,145 per share Disposal price (4) Amount of proceeds JPY 242,346,692,500 to be raised (5) By the Third-Party Allotment, the Company will allot 131,004,000 Offering and disposal shares to Japan Post Holdings Co., Ltd., 57,382,900 shares to Image method Frame Investment (HK) Limited, 14,536,000 shares to Walmart Inc., (expected allotment) 4,366,800 shares to Mikitani Kosan, Inc. and 4,366,800 shares to Spirit Inc. (6) Each of the above items is subject to the notified entries in force, Others based on the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act. * Note: Payment of the Third-Party Allotment is expected to be on March 29, 2021. -

List of Employers of Graduates

Places of Employment of Graduates from Faculty/Graduate School (Master's Program) (2012) Faculty of Letters/Graduate School of Humanities Faculty of Science/Graduate School of Science ● Tama Home Co., Ltd. ● Hitachi Systems, Ltd. ● Hankyu Travel International Co., Ltd. ● Yamazaki Baking Co., Ltd. ● Daikin Industries, Ltd. ● Nippon Telegraph And Telephone West Corp. ● Noevir Co., Ltd. ● Itochu Corp. ● Nara Women's University ● Toray Industries, Inc. ● Murata Manufacturing Co., Ltd. ● Toyo Corp. ● ShinMaywa Industries, Ltd. ● FamilyMart Co., Ltd. ● Osaka Prefectural High School ● Oji Holdings Corp. ● Sharp Corp. ● Aeon Retail Co., Ltd. ● Nikkei Inc. ● Nissen Corp. ● Kyoto Prefectural High School ● Kao Corp. ● Fujitsu Limited ● The Kyoei Fire and Marine Insurance Co., Ltd. ● The Asahi Shimbun Co. ● Yodobashi Camera Co. ● National Tax Administration Agency ● DIC Corp. ● Hitachi, Ltd. ● Institute of Physical and Chemical Research ● NTT Docomo, Inc. ● The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd. ● Osaka District Court ● Sumitomo Chemical Co., Ltd. ● NGK Insulators, Ltd. ● Sumika Chemical Analysis Service, Ltd. ● Obic Co., Ltd. ● Nippon Life Insurance Co. ● Kobe City Office ● Sumitomo Electric Industries, Ltd. ● TIS ● Aeronautical Radio Operator ● Shinchosha Co. ● Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance Co., Ltd. ● Ashiya City Office ● Kobe Steel,Ltd. ● NEC System Technologies, Ltd. ● Teacher (JH&HS) Faculty of Intercultural Studies/Graduate School of Intercultural Studies Graduate school of Medicine (Biomedical Science) ● ASAHI BREWERIES, LTD. ● Kubota Corp. ● Kobe City Office ● Zenyaku Kogyo Co., Ltd. ● TOYO SHINYAKU CO., LTD. ● IKAGAKU ● Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, Ltd. ● Kobe Steel,Ltd. ● Nippon Travel Agency Co., Ltd. ● Shin Nippon Biomedical Laboratories, Ltd. ● Quintiles Inc. ● Crest CO., Ltd. ● Softbank Corp. ● Mitsui & Co., Ltd. ● Rakuten, Inc. ● Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare ● Mediscience Planning Inc. -

OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS Contents Connecting Bluetooth Devices (Optional)

43/49/55 V58 43/49/55 V68 43/49/55 T68 43/49/50/55/65/75 U68 43/49/50/55/65 U58 49/55 U78 OPERATING INSTRUCTIONS Contents Connecting Bluetooth Devices (optional) .............. 29 Environmental Information....................................... 2 Connectivity Troubleshooting ................................ 29 Disposal Information ................................................ 2 Using Audio Video Sharing Network Service ......... 30 Ultra HD (UHD) ........................................................ 3 Apps ...................................................................... 30 High Dynamic Range (HDR) / Hybrid Log-Gamma Internet Browser .................................................... 30 (HLG) ....................................................................... 3 HBBTV System...................................................... 31 Dolby Vision ............................................................. 3 Smart Center ......................................................... 32 Standby Notifications ............................................... 3 Alexa Ready Feature (optional) ............................. 33 TV Control Switch & Operation................................ 3 Using Main TV Menu ............................................... 4 Inserting the Batteries into the Remote ................... 5 Power Connection ................................................... 5 Antenna Connection ................................................ 5 Remote Control ....................................................... 6 Remote -

High-Speed Ethernet Optics

Japan Update Report – September 2020 The Rakuten Mobile effect or lack thereof… ©Copyright 2020 LightCounting www.lightcounting.org Japan Update Report | September 2020 Table of Contents JAPAN UPDATE REPORT – SEPTEMBER 2020 .............................................................................................................. 1 THE RAKUTEN MOBILE EFFECT OR LACK THEREOF… .............................................................................................. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................................................... 3 KEY TAKEAWAYS .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 RAKUTEN MOBILE IS ENTERING A SATURATED YET DEMANDING MARKET .................................................... 5 2018 WAS THE YEAR JAPAN DECIDED TO SHAKE UP ITS OLIGOPOLISTIC MOBILE MARKET ................................................................ 6 THE ENTRY OF A FOURTH PLAYER WAS LONG OVERDUE ........................................................................................................................... 6 JAPAN IS POISED FOR A RELIANCE JIO REDUX ............................................................................................................................................ -

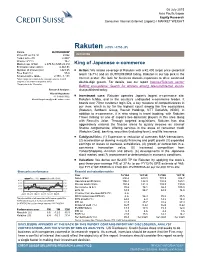

King of Japanese E-Commerce

08 July 2015 Asia Pacific/Japan Equity Research Consumer Internet (Internet (Japan)) / MARKET WEIGHT Rakuten (4755 / 4755 JP) Rating OUTPERFORM* Price (07 Jul 15, ¥) 2,022 INITIATION Target price (¥) 2,400¹ Chg to TP (%) 18.7 Market cap. (¥ bn) 2,878.52 (US$ 23.45) King of Japanese e-commerce Enterprise value (¥ bn) 2,868.91 Number of shares (mn) 1,423.95 ■ Action: We initiate coverage of Rakuten with a ¥2,400 target price (potential Free float (%) 55.0 return 18.7%) and an OUTPERFORM rating. Rakuten is our top pick in the 52-week price range 2,358 - 1,138 *Stock ratings are relative to the coverage universe in each Internet sector. We look for business domain expansion to drive continued analyst's or each team's respective sector. double-digit growth. For details, see our report Internet/Telecom sector: ¹Target price is for 12 months. Battling ecosystems: Search for winners among telecom/Internet stocks, Research Analysts also published today. Hitoshi Hayakawa 81 3 4550 9952 ■ Investment case: Rakuten operates Japan’s largest e-commerce site, [email protected] Rakuten Ichiba, and is the country’s undisputed e-commerce leader. It boasts over 70mn customer login IDs, a key measure of competitiveness in our view, which is by far the highest count among the five ecosystems (Rakuten, Softbank Group, Recruit Holdings, NTT DoCoMo, KDDI). In addition to e-commerce, it is also strong in travel booking, with Rakuten Travel ranking as one of Japan’s two dominant players in this area along with Recruit’s Jalan.