Jonathan Webber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Calculation of Doomsday Based on Anno Domini

SCIENTIFIC CULTURE, Vol. 1, No. 2, (2015), pp. 22-32 Copyright © 2015 SC Open Access. Printed in Greece. All Rights Reserved. The calculation of doomsday based on Anno Domini Sepp Rothwangl Waldwirtschaft Hubertushof Scheibsgraben 49, A-8661 Wartberg, Astria (CALENdeRsign.com;[email protected]) Received: 10/01/2015 Accepted: 15/02/2015 ABSTRACT Anno Domini, or the year Christ’s birth, was an invention made some 1400 years ago by Dionysius Exiguus, who adjusted a new Easter Computus in order to avert end time fever with the pretext to solve a dispute upon the correct date of Easter. Right at the beginning of Christianity, early Christians expected in the near future the return of Christ, which was associated with the end of the world, together with the Seventh Day of the Lord. Such a scenario ocurred already in the cosmic year Anno Mundi (AM) 6,000 based upon a teleological concept by interpreting the Bible. AM produced a calendrical end time with its year 6000 due to equating the Six Days of Genesis with the verse of the Bible saying one Day of the Lord was the same as 1000 years of mankind. To combat the end of the world fever caused by this time concept at the beginning of the 6th century Dionysius Exiguus created a new temporal hinge point for counting the years: Anno Domini. Obviously this chronology is not in harmony with ancient historical works, as even former Pope Benedict XVI recognized, but is an end time prophecy by interpreting the Gospel, the Apocalypse, the scientific cosmology of antiquity, and astronomical values. -

Chapter 5 – Date

Chapter 5 – Date Luckily, most of the problems involving time have mostly been solved and packed away in software and hardware where we, and our customers overseas, do not have to deal with it. Thanks to standardization, if a vender in Peking wants to call a customer in Rome, he checks the Internet for the local time. As far as international business goes, it’s generally 24/7 anyway. Calendars on the other hand, are another matter. You may know what time it is in Khövsgöl, Mongolia, but are you sure what day it is, if it is a holiday, or even what year it is? The purpose of this chapter is to make you aware of just how many active calendars there are out there in current use and of the short comings of our Gregorian system as we try to apply it to the rest of the world. There just isn’t room to review them all so think of this as a kind of around the world in 80 days. There are so many different living calendars, and since the Internet is becoming our greatest library yet, a great many ancient ones that must be accounted for as well. We must consider them all in our collations. As I write this in 2010 by the Gregorian calendar, it is 2960 in Northwest Africa, 1727 in Ethopia, and 4710 by the Chinese calendar. A calendar is a symbol of identity. They fix important festivals and dates and help us share a common pacing in our lives. They are the most common framework a civilization or group of people can have. -

IMPORTANT DATES of the YEAR Date-Time of The

IMPORTANT DATES OF THE YEAR Date-Time of the Spring Equinox of the current year Date-Time of the Summer Solstice of the current year Date-Time of the Fall Equinox of the current year Date-Time of the Winter Solstice of the current year Orthodox Easter Catholic Easter THE CURRENT DATE (TODAY) Julian Day Number (JDN): Number of days that have passed since the start of the current Julian period with day 0 the 1st of Jan. 4713 BC (in proletic Julian Calendar). This counting has been introduced by Scaliger in 1583. It gives only the ordinal number of any date independently of following Julian Calendar (before 5/10/1582) or Gregorian Calendar (introduced on 5/10/1582 transformed to 15/10/1582). Ancient Attic (Athenian Calendar): Year numbering from the start of Olympics (776 BC) Roman Calendar based on Nones, Ides, Kalends. Year numbering from the year of creation or Rome: Ab Urbe Condita (AUC) = 753 BC Byzantine Annus Mundi: Year numbering from the creation of the world (1st of Sept.5509 BC) according to Byzantines. Used by the Orthodox Church during the Byzantine Era. Byzantine years start on 1st of Sept. Indiction: The order of a year in a repeated 15-year cycle started in 297-298 AD in Roman Egypt and continues in Byzantines Hebrew Calendar (Anno Mundi): Year numbering from the date of the creation of the world for Jews: proleptic Julian 7th of Oct. 3761 BC. Hijri (Islamic) Calendar: Year numbering from 622 AD (1 AH – year of Hegira). Coptic Calendar (Anno Martyri/ Diocletiani). -

BIBLE CHRONOLOGY STATED As B.C. and A.M. the Arrangement of Chronology in Our Common Version English Bibles Was Made by Bishop Usher

BIBLE CHRONOLOGY STATED as B.C. and A.M. THE arrangement of Chronology in our Common Version English Bibles was made by Bishop Usher. It begins with the era known as Anno Domini (the year of our Lord--although Usher believed, with many scholars, that our Lord was born 4 years earlier than that era,—and we claim 1-¼ years earlier.) Usher reckons backward from A.D., calling the years B.C. The table below lists the Biblical years according to the common era (B.C.). Since some might prefer to see the counting beginning from Adam’s creation as a zero point, a second column is included known as A.M. (Anno Mundi) or the year of the world. Each Biblical period is advanced from the corresponding B.C. or A.M. points. Dates are noted in customary whole years beginning in January. However, a precise accounting may be reckoned 3 months earlier according to the Hebrew secular calendar, making Adam’s creation in the Autumn of 4129 and 6000 ending in the Autumn of 1872. Page two picks up the fixed point in chronology marked as the covenant with Abraham, and proceeding with the Biblical bridge supplied in Exodus and Galatians extending to the Exodus. Otherwise, we would not know the years between the death of Jacob and the Exodus from Egypt. God created Adam BC 4128 AM 0 Gen.2:7; 5:1 had a son at 130 Gen. 5:3 Seth born BC 3998 AM 130 had a son at 105 Gen. 5:6 Enos born BC 3893 AM 235 had a son at 90 Gen. -

Calendar -Where Are We Now.Pdf

History of the Calendar WHERE ARE WE NOW? WHAT YEAR IS IT REALLY? OUR WESTERN CALENDAR The calendar as we know it has evolved from a Roman calendar established by Romulus, consisting of a year of 304 days divided into 10 months, commencing with March. modified by Numa, added two extra months, January and February, making a year consist of 12 months of 30 and 29 days alternately plus one extra day and thus a year of 355 days. required an Intercalary month of 22 or 23 days in alternate years. In the year 46 B.C. Julius Caesar asked for the help of the Egyptian astronomer Sosigenes, had found that the calendar had fallen into some confusion. led to the adoption of the Julian calendar in 45 B.C. 46 B.C. was made to consist of 445 days to adjust for earlier faults known as the "Year of Confusion". In the Christian system, years are distinguished by numbers before or after the Incarnation denoted by the letters B.C. (Before Christ) and A.D. (Anno Domini). The starting point is the Jewish calendar year 3761 A.M. (Anno Mundi) and the 754th year from the foundation of Rome. said to have been introduced into England by St. Augustine about 596 A.D. not in general use until ordered by the bishops at council of Chelsea 816 A.D. The Julian calendar all centennial years were leap years (ie the years A.D. 1200, 1300, 1400 etc.) end of the 16th century difference of 10 days between the Tropical and calendar years. -

Jewish Calendar in the Roman Period: in Search of a Viable Calendar System

JEWISH CALENDAR IN THE ROMAN PERIOD: IN SEARCH OF A VIABLE CALENDAR SYSTEM Ari Belenkiy Mathematics Department, Bar-Ilan University, Israel Introduction The calendar system which Jews use now was known to Babylonians at least at the end of the 4th cent. BCE. This allows Jewish apologetes to claim that this was the ancient Jewish system copied by the Chaldeans after the conquest of Judea in the 6th century BCE. Even so, after the second national catastrophe in 70 CE, we see a remarkable break with this tradition - Jewish leaders rely on immediate observations of the new moon to fix the first day of the month and the ripeness of fruit to intercalate an additional month in the lunar calendar rather than mathematics. There are no signs that the astronomical achievements of ancient Greece and Babylon were used by Jews in the first five centuries of the Christian Era. Meanwhile, defeats in the two great wars against Rome in 70 and 135 CE caused a flow of refugees to the neighboring countries, mainly to Babylonia. At first the notes about all the decisions rendered by the calendar council were passed by fire signals or by messengers, but soon both systems were inadequate. This caused Jews to look for a fixed calendar system. We discuss here two such systems. They are simple and can be called "arithmetical.c This period is fairly well recorded in the Talmud, albeit with significant omissions, and we have to reconstruct some missing parts of those systems. For this purpose the evidence of Christian authors, contemporaries of these events, are most important. -

Revised Ancient Biblical Timeline

PREFACE When I decided to write this book, I found I had two things to consider. One was what the book would say; and the other was what motivated me to write it. A brief account of why I chose to write this book can help make the nature of the work more understandable. For this reason, I will tackle the second consideration first. Like most Christians, I grew up with bible stories. I came to believe in the truth of what the Bible said. As my education in science developed, I also came to believe in the truth of the scientific model of the universe and the development of the human species. However, I was troubled. There did not seem to be much physical evidence to show that the descriptive picture presented in the Bible actually matched the scientific model. For instance, Noah's flood is a well-known story, and pivotal event in biblical history; but the physical evidence is lacking. People have been looking for Noah's ark without success for over 200 years; and, there seems to be no evidence of flood debris in the Middle East around the time when the Bible says it should be, ~2300 BC. This is just one example of a lack of scientific evidence available to support the biblical account. After much study I discovered, what I believe, shows how both the scientific picture and the biblical picture are telling the same true story. Only the audience is different. I discovered that there really is physical evidence to support biblical events. -

Which Is the Correct Calendar: the Pagan One the Western World Uses

WHICH IS THE CORRECT CALENDAR: THE PAGAN ONE THE WESTERN WORLD USES OR THE BIBLICAL ONE? IS IT TRUE THAT OUR DAY & MONTH NAMES ORIGINATE FROM GODS THE PAGANS DEARLY WORSHIPPED? WE INFORM – YOU CHOOSE PROFESSOR WA LIEBENBERG 0 WHICH IS THE CORRECT CALENDAR: THE PAGAN ONE THE WESTERN WORLD USES OR THE BIBLICAL ONE? By WA Liebenberg Proofread by: Lynette Schaefer All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or copied. Distributed by: Hebraic Roots Teaching Institute Pretoria – South Africa Email: [email protected] Mobile: +27 (0)83 273 1144 Facebook Page: “The Hebraic Roots Teaching Institute” Website: www.hrti.co.za 1 Preface YHWH “God” has called us to do two things. First, we are to never give up studying and seeking the correct interpretation of any given Bible passage. Second, such opportunities are golden moments for us to learn to show grace and love to others whose understanding of a given passage may differ from ours. Throughout the HRTI’s teachings we use a slightly different vocabulary to that which some might be accustomed. We have chosen to use what many refer to as a Messianic vocabulary. The reasons being: Firstly, using Hebraic-sounding words is another way to help you associate with the Hebraic Roots of your faith. Secondly, these words are not merely an outward show for us, they are truly an expression of who we are as Messianic Jews and Gentiles who have "taken hold" of our inheritance with Israel. Instead of saying "Jesus," we call our Saviour "Y’shua," the way His parents would have addressed Him in Hebrew. -

The Essenes Calendar and the Last Days

The Essenes Calendar and The Last Days The Greeks controlled Palestine/Israel from 323BC to 164BE when Judas Maccabees and his brethren revolted against the Greeks and defeated them. The Greeks had imposed their culture on Israel which caused many to leave the customs and traditions but worse than that they also imposed their Calendar upon the people. The Maccabees turned things around, but they did not return to God’s Calendar which had been used since the times of Adam and Eve. Then one of the Maccabean High Priests, John Hyrcanus I took the title of High Priest and King. That was forbidden and caused a deep split in the people. Those who felt that they needed to follow the High Priest no matter what he did or said were known as the Sadducees. These were the “ruling class” and they rejected certain doctrines as “resurrection, judgement for life, existence of angels”. The Jews who refused to follow John Hyrcanus I as High Priest were known as the Pharisees or “the Separated Ones”. They followed a strict, legalistic interpretation of the Law of Moses and the Teachings of the Rabbis. The Sadducees and Pharisees actually fought a War between them that lasted for 8 years from 96- 88BC. Everyone claimed to be the rightful rulers and kept trying to assassinate the leaders of the opposing party. Rome defeated the Jews in 135 and ruled from then on until they placed John Hyrcanus II into power. Civil order was still not restored so the Romans put Herod, an Idumean, as King in 37BC. -

First-Century Chronology

End Times Prophecy 314: First-Century Chronology biblestudying.net Brian K. McPherson and Scott McPherson Copyright 2012 The First-Century Apostolic Understanding of Chronology Below are three premises that we want to discuss and compare in this brief study. 1. The apostles understood the amount of time from creation to Christ to include around 4,000 years. 2. Statements in the New Testament indicate that the apostles felt that Christ’s return could occur in the first century AD. 3. The apostles taught that the creation week which was composed of six days of work followed by a seventh day of rest would be paralleled in the course of history such that the kingdom of Christ would include a millennial reign of Christ on earth which was proceeded by 6,000 years of history starting at creation itself. The first statement is probably taken for granted, but may not often be the focus of much discussion and it may not have much doctrinal significance other than its inclusion under the larger concept that the apostles accurately understood all biblical teaching. The second statement articulates a very common perception that can be derived from certain plain statements that occur in the New Testament. There is no inherent difficulty with simultaneously accepting both these two conclusions. However, once we add the third point into the discussion, contradiction arises. For, if the apostles understood 4,000 years had occurred prior to Christ’s first coming and they believed that Christ could return in the first century AD then they could not have taught that Christ’s return and his kingdom could only occur after 6,000 years of history. -

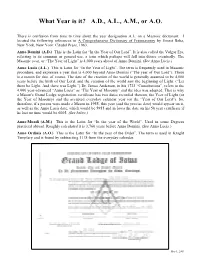

What Year Is It? A.D., A.L., A.M., Or A.O

What Year is it? A.D., A.L., A.M., or A.O. There is confusion from time to time about the year designation A.L. on a Masonic document. I located the following references in A Comprehensive Dictionary of Freemasonry by Ernest Beha, New York, New York: Citadel Press, 1963. Anno Domini (A.D.) This is the Latin for “In the Year of Our Lord”. It is also called the Vulgar Era, referring to its common or general use, a term which perhaps will fall into disuse eventually. The Masonic year, or “The Year of Light” is 4,000 years ahead of Anno Domini. (See Anno Lucis.) Anno Lucis (A.L.) This is Latin for “In the Year of Light”. The term is frequently used in Masonic procedure, and expresses a year that is 4,000 beyond Anno Domini (“The year of Our Lord”). There is a reason for this, of course. The date of the creation of the world is generally assumed to be 4,000 years before the birth of Our Lord, and the creation of the world saw the beginning of Light. (“Let there be Light. And there was Light.”) Dr. James Anderson, in his 1723 “Constitutions”, refers to the 4,000 year-advanced “Anno Lucis” as “The Year of Masonry” and the idea was adopted. That is why a Mason's Grand Lodge registration certificate has two dates recorded thereon, the Year of Light (or the Year of Masonry) and the accepted everyday calendar year (or the “Year of Our Lord”). So, therefore, if a person were made a Mason in 1955, this year (and the precise date) would appear on it, as well as the Anno Lucis date, which would be 5955 and in Iowa the date on his 50 year certificate if he lost no time would be 6005. -

AM Chronology (Anno Mundi “Year of the World”)

A.M. Chronology (Anno Mundi “Year of the World”) Genesis 5, 11:10 A.M. 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 2000 Adam 130 AM 930 AM Adam dies 235 AM 105 yrs + 807 yrs after Enosh’s birth 1042 AM Seth dies Seth @ 912 yrs old 325 AM Enosh 90 yrs + 815 yrs after Cainan’s birth 1130 AM Enosh dies @ 905 yrs old 395 AM Cainan 70yrs + 840 yrs after Mahahalel’s birth 1235 AM Cainan dies @ 910 yrs old 460 AM Mahahalel 65yrs + 830 yrs after Jared’s birth 1290 AM Mahahalel dies @ 895 yrs old 622 AM Jared 162 yrs + 800 yrs after Enoch’s birth 1422 AM Jared dies @ 962 yrs old 687 AM Enoch 65yrs + 300 yrs 987 AM Enoch “taken” @ 365 yrs old 874 AM Methuselah 187 yrs + 782 yrs after Lamech’s birth 1656 AM Methusaleh dies @ 969 yrs old 1056 AM Lamech 182 yrs + 595 yrs after Noah’s birth 1651 AM Lamech dies (Adam died when Lamech was 56 yrs old) @ 777 yrs old 1556 AM 1558 AM 2006 AM Observations : 1656 AM Noah dies 1. Cain may have killed Abel when he was about 128 years old Noah FLOOD @ 950 because Seth was born soon after the murder, when Adam was 130. When Noah was 500 yrs old 2. Methuselah died right before the flood that year. Since this is the line of the covenant Japheth was born first leading up to Noah we know this is a list of godly people.