Exploring Coordinative Mechanisms for Environmental Governance in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area: an Ecology of Games Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

Lands Administration Office Lands Department

Lands Administration Office Lands Department Practice Note Issue No. 7/2019 Provision of Transitional Housing in Converted Existing Industrial Building This Practice Note supplements (i) Lands Department ("LandsD") Lands Administration Office ("LAO") Practice Note No. 1/2010 as varied by LandsD LAO Practice Note Nos. I/2010A and 1/2010B (collectively "1/2010 PNs") and supplemented by LandsD LAO Practice Note No. 2/2016; and (ii) LandsD LAO Practice Note No. 6/2019 ("PN 6/20 19"), both of which are in relation to special waiver for conversion of an entire existing industrial building for non-industrial purposes (collectively "Special Waiver"). 2. In accordance with Government's prevailing policy of facilitating community-initiated transitional housing projects, owners may apply for a waiver (as part of or in addition to the application for the Special Waiver, or otherwise) for the conversion of an existing industrial building and for the provision and use of the converted industrial building or part thereof, situated in an area zoned "Commercial", "Comprehensive Development Area", "Other Specified Uses" annotated "Business", or "Residential" according to the statutory town plans prepared pursuant to the Town Planning Ordinance, any regulations made thereunder and any amending legislation (collectively "TPO"), for transitional housing purposes ("Transitional Housing Waiver") for a term of not more than five (5) years provided that: (a) the transitional housing is to be run by a non-profit making organisation 1 or social enterprise2 (collectively "NGOs") and the waiver application is supported by the Transport and Housing Bureau ("THB"). To this end, the Task Force on Transitional Housing ("Task Force") has been established under THB to provide one-stop facilitation; and (b) the temporary use as transitional housing is permitted under the statutory town 3 plans prepared pursuant to the TP0 . -

Development of Catchwater System Management Plan - Prioritisation of Catchwater Systems - Feasibility Study

Water Supplies Department W The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Agreement No. CE 37/2010 (WS) Development of Catchwater System Management Plan - Prioritisation of Catchwater Systems - Feasibility Study Draft BRIEF (7 Apr il 2011) W Water Supplies Department Agreement No. CE 37/2010 (WS) Agreement No. CE 37/2010 (WS) Development of Catchwater System Management Plan - Prioritisation of Catchwater Systems - Feasibility Study DRAFT BRIEF Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................ ................................ ................................ ...................... 1 2. Description of the Project ................................ ................................ ............................... 1 3. Objective s of the Assignment ................................ ................................ ........................ 5 4. Description of the Assignment ................................ ................................ ....................... 5 5. Deliverables ................................ ................................ ................................ ...................... 6 6. Services to be provided by the Consultants ................................ ................................ 13 7. Response to Queries ................................ ................................ ................................ ...... 25 8. Programme of Implementation ................................ ................................ .................... 25 9. Progress Reports ............................... -

As at Early February 2012)

Annex Government Mobile Applications and Mobile Websites (As at early February 2012) A. Mobile Applications Name Departments Tell me@1823 Efficiency Unit Where is Dr Sun? Efficiency Unit (youth.gov.hk) Youth.gov.hk Efficiency Unit (youth.gov.hk) news.gov.hk Information Services Department Hong Kong 2010 Information Services Department This is Hong Kong Information Services Department Nutrition Calculator Food and Environmental Hygiene Department Snack Nutritional Classification Wizard Department of Health MyObservatory Hong Kong Observatory MyWorldWeather Hong Kong Observatory Hongkong Post Hongkong Post RTHK On The Go Radio Television Hong Kong Cat’s World Radio Television Hong Kong Applied Learning (ApL) Education Bureau HKeTransport Transport Department OFTA Broadband Performance Test Office of the Telecommunications Authority Enjoy Hiking Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Hong Kong Geopark Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Hong Kong Wetland Park Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Reef Check Hong Kong Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Quit Smoking App Department of Health Build Up Programme Development Bureau 18 Handy Tips for Family Education Home Affairs Bureau Interactive Employment Service Labour Department Senior Citizen Card Scheme Social Welfare Department The Basic Law Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau B. Mobile Websites Name Departments Tell me@1823 Website Efficiency Unit http://mf.one.gov.hk/1823mform_en.html Youth.gov.hk Efficiency Unit http://m.youth.gov.hk/ -

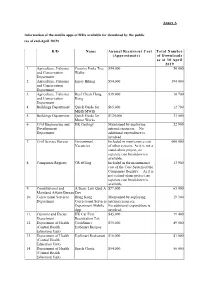

Information of the Mobile Apps of B/Ds Available for Download by the Public (As of End-April 2019)

Annex A Information of the mobile apps of B/Ds available for download by the public (as of end-April 2019) B/D Name Annual Recurrent Cost Total Number (Approximate) of Downloads as at 30 April 2019 1. Agriculture, Fisheries Country Parks Tree $54,000 50 000 and Conservation Walks Department 2. Agriculture, Fisheries Enjoy Hiking $54,000 394 000 and Conservation Department 3. Agriculture, Fisheries Reef Check Hong $39,000 10 700 and Conservation Kong Department 4. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $65,000 12 700 MBIS/MWIS 5. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $120,000 33 000 Minor Works 6. Civil Engineering and HK Geology Maintained by deploying 22 900 Development internal resources. No Department additional expenditure is involved. 7. Civil Service Bureau Government Included in maintenance cost 600 000 Vacancies of other systems. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 8. Companies Registry CR eFiling Included in the maintenance 13 900 cost of the Core System of the Companies Registry. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 9. Constitutional and A Basic Law Quiz A $77,000 65 000 Mainland Affairs Bureau Day 10. Correctional Services Hong Kong Maintained by deploying 19 300 Department Correctional Services internal resources. Department Mobile No additional expenditure is App involved. 11. Customs and Excise HK Car First $45,000 19 400 Department Registration Tax 12. Department of Health CookSmart: $35,000 49 000 (Central Health EatSmart Recipes Education Unit) 13. Department of Health EatSmart Restaurant $16,000 41 000 (Central Health Education Unit) 14. -

Women's Development in Guangdong; Unequal Opportunities and Limited Development in a Market Economy

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2012 Women's Development in Guangdong; Unequal Opportunities and Limited Development in a Market Economy Ying Hua Yue CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/169 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Running head: WOMEN’S DEVELOPMENT IN GUANGDONG 1 Women’s Development in Guangdong: Unequal Opportunities and Limited Development in a Market Economy Yinghua Yue The City College of New York In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology Fall 2012 WOMEN’ S DEVELOPMENT IN GUANGDONG 2 ABSTRACT In the context of China’s three-decade market-oriented economic reform, in which economic development has long been prioritized, women’s development, as one of the social undertakings peripheral to economic development, has relatively lagged behind. This research is an attempt to unfold the current situation of women’s development within such context by studying the case of Guangdong -- the province as forerunner of China’s economic reform and opening-up -- drawing on current primary resources. First, this study reveals mixed results for women’s development in Guangdong: achievements have been made in education, employment and political participation in terms of “rates” and “numbers,” and small “breakthroughs” have taken place in legislation and women’s awareness of their equal rights and interests; however, limitations and challenges, like disparities between different women groups in addition to gender disparity, continue to exist. -

AEPS Summary Report

SUMMARY OF EXPENDITURE ESTIMATES Actual Approved Revised expenditure estimate estimate Estimate HEAD OF EXPENDITURE 2007–08 2008–09 2008–09 2009–10 –––––––––– –––––––––– –––––––––– –––––––––– $’000 $’000 $’000 $’000 21 Chief Executive’s Office ......................... 77,429 79,145 81,406 84,507 22 Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department.......................................... 1,458,086 897,545 1,122,606 930,068 25 Architectural Services Department.......... 1,391,110 1,432,348 1,470,144 1,521,318 24 Audit Commission................................... 114,522 119,263 121,397 122,364 23 Auxiliary Medical Service....................... 59,738 63,633 64,410 70,154 82 Buildings Department.............................. 783,243 825,042 835,750 890,638 26 Census and Statistics Department............ 455,302 484,715 472,098 553,424 27 Civil Aid Service ..................................... 72,324 80,831 82,484 82,067 28 Civil Aviation Department ...................... 605,238 677,479 669,536 712,824 33 Civil Engineering and Development Department.......................................... 1,302,260 1,431,120 1,456,591 2,115,033 30 Correctional Services Department........... 2,484,866 2,539,155 2,624,261 2,698,592 31 Customs and Excise Department............. 2,052,986 2,308,147 2,276,242 2,485,416 37 Department of Health .............................. 3,075,435 3,344,211 3,435,037 4,120,690 92 Department of Justice .............................. 855,181 949,200 941,136 1,004,363 39 Drainage Services Department ................ 1,601,314 1,638,608 1,676,333 1,769,653 42 Electrical and Mechanical Services Department.......................................... 302,889 309,160 319,093 463,722 44 Environmental Protection Department .... 3,254,009 3,349,442 2,552,670 3,202,669 45 Fire Services Department ....................... -

Government Secretariat: Development Bureau (Planning and Lands Branch)

Head 138 — GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT: DEVELOPMENT BUREAU (PLANNING AND LANDS BRANCH) Controlling officer: the Permanent Secretary for Development (Planning and Lands) will account for expenditure under this Head. Estimate 2021–22 .................................................................................................................................... $1,785.5m Establishment ceiling 2021–22 (notional annual mid-point salary value) representing an estimated 195 non-directorate posts as at 31 March 2021 rising by seven posts to 202 posts as at 31 March 2022 .......................................................................................................................................... $155.2m In addition, there will be an estimated 15 directorate posts as at 31 March 2021 and as at 31 March 2022. Commitment balance.............................................................................................................................. $8,749.3m Controlling Officer’s Report Programmes Programme (1) Director of Bureau’s Office This Programme contributes to Policy Area 27: Intra-Governmental Services (Secretary for Development). Programme (2) Buildings, Lands and This Programme contributes to Policy Area 22: Buildings, Planning Lands, Planning, Heritage Conservation, Greening and Landscape (Secretary for Development). Detail Programme (1): Director of Bureau’s Office 2019–20 2020–21 2020–21 2021–22 (Actual) (Original) (Revised) (Estimate) Financial provision ($m) 17.1 17.2 16.8 17.2 (–2.3%) (+2.4%) (or same as 2020–21 Original) -

List of Abbreviations

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AAHK Airport Authority Hong Kong AAIA Air Accident Investigation Authority AFCD Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department AMS Auxiliary Medical Service ASC Aviation Security Committee ASD Architectural Services Department BD Buildings Department CAD Civil Aviation Department CAS Civil Aid Service CCCs Command and Control Centres CEDD Civil Engineering and Development Department CEO Chief Executive’s Office / Civil Engineering Office CESC Chief Executive Security Committee CEU Casualty Enquiry Unit CIC Combined Information Centre CS Chief Secretary for Administration DECC District Emergency Co-ordination Centre DEVB Development Bureau DH Department of Health DO District Officer DSD Drainage Services Department EDB Education Bureau EMSC Emergency Monitoring and Support Centre EMSD Electrical and Mechanical Services Department EPD Environmental Protection Department EROOHK Emergency Response Operations Outside the HKSAR ESU Emergency Support Unit ETCC Emergency Transport Coordination Centre FCC Food Control Committee FCP Forward Control Point FEHD Food and Environmental Hygiene Department FSCC Fire Services Communication Centre FSD Fire Services Department GEO Geotechnical Engineering Office GFS Government Flying Service GL Government Laboratory GLD Government Logistics Department HA Hospital Authority HAD Home Affairs Department HD Housing Department HyD Highways Department HKO Hong Kong Observatory HKPF Hong Kong Police Force HKSAR Hong Kong Special Administrative Region HQCCC Police Headquarters Command -

Strongly Heterogeneous Transmission of COVID–19 in Mainland China: Local and Regional Variation

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.10.20033852; this version posted March 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Strongly heterogeneous transmission of COVID–19 in mainland China: local and regional variation Yuke Wang, MSc1, Peter Teunis, PhD1 March 10, 2020 Summary Background The outbreak of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) started in the city of Wuhan, China, with a period of rapid initial spread. Transmission on a regional and then national scale was promoted by intense travel during the holiday period of the Chinese New Year. We studied the variation in transmission of COVID-19, locally in Wuhan, as well as on a larger spatial scale, among different cities and even among provinces in mainland China. Methods In addition to reported numbers of new cases, we have been able to assemble detailed contact data for some of the initial clusters of COVID-19. This enabled estimation of the serial interval for clinical cases, as well as reproduction numbers for small and large regions. Findings We estimated the average serial interval was 4·8 days. For early transmission in Wuhan, any infectious case produced as many as four new cases, transmission outside Wuhan was less in- tense, with reproduction numbers below two. During the rapid growth phase of the outbreak the region of Wuhan city acted as a hot spot, generating new cases upon contact, while locally, in other provinces, transmission was low. -

Head 91 — LANDS DEPARTMENT

Head 91 — LANDS DEPARTMENT Controlling officer: the Director of Lands will account for expenditure under this Head. Estimate 2002–03................................................................................................................................... $1,727.6m Establishment ceiling 2002–03 (notional annual mid-point salary value) representing an estimated 3 548 non-directorate posts at 31 March 2002 rising by 179 posts to 3 727 posts at 31 March 2003 ..... $1,188.7m In addition there will be an estimated 52 directorate posts at 31 March 2002 and at 31 March 2003. Capital Account commitment balance................................................................................................. $21.1m Controlling Officer’s Report Programmes Programme (1) Land Administration These programmes contribute to Policy Area 21: Transport Programme (2) Survey and Mapping (Secretary for Transport), Policy Area 22: Buildings, Lands and Programme (3) Legal Advice Planning (Secretary for Planning and Lands) and Policy Area 31: Housing (Secretary for Housing). Detail Programme (1): Land Administration 2000–01 2001–02 2001–02 2002–03 (Actual) (Approved) (Revised) (Estimate) Financial provision ($m) 1,041.7 1,152.0 1,149.0 1,242.8 (+10.6%) (–0.3%) (+8.2%) Aim 2 The aim is to administer land in Hong Kong by disposing of land; acquiring private land and clearing private and government land required for the implementation of public works and other projects; managing government leases and unleased land and certain buildings held by the Administration; re-granting and modifying leases; and maintaining man- made slopes on unallocated and unleased government land. Brief Description 3 The Lands Department disposes of land through the Land Sale Programme. It acquires private land and clears private and government land required for public works projects or other approved schemes. -

Circular Letter No. 7/2019 Electronic Submission for Applications for Water Supplies to New Village Type Houses Using Pre-Approved Standard Plumbing Design Drawings

水 務 署 W Water Supplies Department 總部 Headquarters 香港灣仔告士打道七號入境事務大樓 48 樓 48/F, Immigration Tower, 7 Gloucester Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 本署檔號 電話 : (15) in WSD 3318/50 Pt. 7 : 2829 4355 Our ref. Tel. 來函檔號 傳真 : : 2824 0578 Your ref. Fax. 5 September 2019 Distribution: To all Licensed Plumbers and Authorized Persons Dear Sirs, Circular Letter No. 7/2019 Electronic Submission for Applications for Water Supplies to New Village Type Houses using Pre-approved Standard Plumbing Design Drawings Pre-approved Standard Plumbing Design Drawings (“Standard Plumbing Designs”) Owing to the relatively simple nature and high degree of similarity among plumbing designs of village type houses, some LP associations/institutions have developed a number of commonly used plumbing designs for village type houses including standard Vertical Plumbing Line Diagrams and standard meter box arrangements, and have obtained pre-approval from the Water Authority (“WA”) confirming the compliance of these plumbing designs with statutory and WA requirements. A list of the standard plumbing designs for village type houses is given in Appendix A and drawings of the standard designs could be found at the official websites of relevant LP associations/institutions as given in Appendix B. They are the copyright owners of these standard design drawings and have agreed to share these designs for use by LPs in application for water supplies, exchange of technical knowledge and educational purposes. Electronic Submission 2. To enhance the efficiency of processing applications for water supplies to village type houses, the Water Supplies Department (WSD) will allow electronic 2 submission for the application for water supply for new village type houses adopting standard plumbing designs in plumbing proposals.