Panels and Prose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R Ev Ista D Ig Ita L Min a Tu R a (S Inc E 1999) November -December # 147

The magazine of the Brief & Fantastic November -December # 147 2015 Revista digital miNatura (Since Revista 1999) miNatura digital 1 The magazine of the Brief & Fantastic November -December # 147 2015 It sounds plausible enough tonight, I was. I tell you, an enchanted but wait until tomorrow. Wait for the garden. I know. And the size? Oh! it common sense of the morning. stretched far and wide, this way and H.G. Wells, The Time Machine. that. I believe there were hills far away. Heaven knows where West Kensington had suddenly got to. And Alone-- it is wonderful how little a somehow it was just like coming man can do alone! To rob a little, to home. hurt a little, and there is the end. H.G. Wells, The door in the wall. H.G. Wells, The Invisible Man. After telephone, kinematograph and phonograph No one would have believed in the last years of had replaced newspaper, book schoolmaster and the nineteenth century that this world was being letter, to live outside the range of the electric watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater cables was to live an isolated savage. than man's and yet as mortal as his own; that as H.G. Wells, The Sleeper Awakes. men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinized and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a The past is only the beginning of a beginning. microscope might scrutinize the transient H.G. Wells, The Crystal Egg and Other Tales. creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

V for Vendetta

Study Guide: V For Vendetta popular in that title; during the 26 issues of Warrior several covers featured V for Vendetta. When the publishers cancelled Warrior in 1985 (with two completed issues unpublished due to the cancellation), several companies attempted to convince Moore and Lloyd to let them publish and complete the story. In 1988 DC Comics published a ten-issue series that reprinted the Warrior stories in color, then continued the series to completion. The first new material appeared in issue #7, which included the unpublished episodes that would have appeared in Warrior #27 and #28. Tony Weare drew one chapter ("Vincent") and contributed additional art to two others ("Valerie" and "The Vacation"); Steve Whitaker and Siobhan Dodds worked as colourists on the entire series. The series, including Moore's "Behind the Painted ! Smile" essay and two "interludes" outside the central continuity, then appeared in collected form as a trade The complete film script of V for Vendetta is paperback, published in the US by DC's Vertigo imprint available from the Internet Movie Script Database: (ISBN 0-930289-52-8) and in the UK by Titan Books http://www.imsdb.com/scripts/V-for-Vendetta.html (ISBN 1-85286-291-2). V for Vendetta is a ten-issue comic book series written by Alan Moore and illustrated mostly by David Background Lloyd, set in a dystopian future United Kingdom David Lloyd's paintings for V for Vendetta in imagined from the 1980s to about the 1990s. A Warrior originally appeared in black-and-white. The DC mysterious masked revolutionary who calls himself "V" Comics version published the artwork "colourised" in works to destroy the totalitarian government, profoundly pastels. -

Ricardo Spinelli V for VENDETTA: from BOOKS and BOOK

Ricardo Spinelli V FOR VENDETTA: FROM BOOKS AND BOOK MARKETS INTO REAL WORLDS. A study of V for Vendetta and its extent provided by translation Dissertation presented to the course at PGET (Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos da Tradução) at Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, as a partial requisite to obtain a Master’s Degree. Advisor: Prof. Dr. José Cyriel Gerard Lambert Florianópolis - SC 2015 Ricardo Spinelli V FOR VENDETTA: FROM BOOKS AND BOOK MARKETS INTO REAL WORDS A study of V for Vendetta and its extent provided by translation Esta Dissertação foi julgada adequada para obtenção do Título de “Mestre em Estudos da Tradução”, e aprovada em sua forma final pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos da Tradução da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Florianópolis, 09 de março de 2015. ____________________________ Prof. Andréia Guerini, Dra. Coordenadora do Curso Banca Examinadora: ___________________________ Prof. Dr. José Cyriel Gerard Lambert (Orientador) Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina - UFSC ___________________________ Prof.ª Marie-Hélène Catherine Torres, Dr.ª. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina – UFSC/PGET __________________________ Prof. Maicon Tenfen, Dr. Fundação Universidade Regional de Blumenau - FURB ___________________________ Prof. Lincoln Fernandes, Dr. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina – UFSC/PGET For my wife, Helena. You have been my lifelong companion. Thank you for believing in this project and being by my side throughout this journey. For my son, Guilherme. Thank you for reintroducing me to the world of Sequential Art years ago. Without it, this dissertation would have never come to life. For my daughter, Bianca. Thank you for your reassuring words when I least expected them – and when I needed them most. -

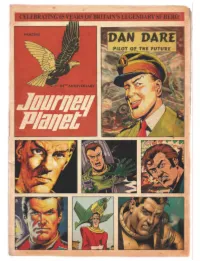

Journey Planet 24 - June 2015 James Bacon ~ Michael Carroll ~ Chris Garcia Great Newseditors Chums! The

I I • • • 1 JOURNEY PLANET 24 - JUNE 2015 JAMES BACON ~ MICHAEL CARROLL ~ CHRIS GARCIA GREAT NEWSEDITORS CHUMS! THE Dan Dare and related characters are (C) the Dan Dare Corporation. All other illustrations and photographs are (C) their original creators. Table of Contents Page 3 - Some Years in the Future - An Editorial by Michael Carroll Dan Dare in Print Page 6 - The Rise and Fall of Frank Hampson: A Personal View by Edward James Page 9 - The Crisis of Multiple Dares by David MacDonald Page 11 - A Whole New Universe to Master! - Michael Carroll looks back at the 2000AD incarnation of Dan Dare Page 15 - Virgin Comics’ Dan Dare by Gary Eskine Page 17 - Bryan Talbot Interviewed by James Bacon Page 19 - Making the Old New Again by Dave Hendrick Page 21 - 65 Years of Dan Dare by Barrie Tomlinson Page 23 - John Higgins on Dan Dare Page 26 - Richard Bruton on Dan Dare Page 28 - Truth or Dare by Peppard Saltine Page 31 - The Bidding War for the 1963 Dan Dare Annual by Steve Winders Page 33 - Dan Dare: My Part in His Revival by Pat Mills Page 36 -Great News Chums! The Eagle Family Tree by Jeremy Briggs Dan Dare is Everywhere! Page 39 - Dan Dare badge from Bill Burns Page 40 - My Brother the Mekon and Other Thrilling Space Stories by Helena Nash Page 45 - Dan Dare on the Wireless by Steve Winders Page 50 - Lego Dan Dare by James Shields Page 51 - The Spacefleet Project by Dr. Raymond D. Wright Page 54 - Through a Glass Darely: Ministry of Space by Helena Nash Page 59 - Dan Dare: The Video Game by James Shields Page 61 - Dan Dare vs. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Moore, Alan. editorial. Embryo 1 (c. September 1970). Moore, Alan. editorial. Embryo 2 (December 1970). Moore, Alan. ‘A Voice of Flame’. Embryo 2 (December 1970). Moore, Alan ‘Deathshead’. Embryo 2 (December 1970). Moore, Alan. ‘Ministry of Love’. Embryo 2 (December 1970). Moore, Alan. “Paranopolis”, Embryo 2 (December 1970). Moore, Alan. ‘The Brain of Night’. Embryo 2 (December 1970). Moore, Alan. editorial. Deliver Us From All Rovel (1971). Moore, Alan. Rupert illustration. Embryo 3 (February 1971). Moore, Alan. ‘Mindfare Neurosis 80’. Embryo 3 (February 1971). Moore, Alan. “Breakdown”. Embryo 4 (c. May 1971). Moore Alan. ‘Once There Were Daemons’. Deliver Us From All Rovel (1971) and Embryo 5 (November 1971). Moore, Alan. ‘The Electric Pilgrim Zone Two’. Bedlam (1973) 18–19. Moore, Alan. ‘Anon E. Mouse’. ANON. Alternative Newspaper of Northampton 3 (Feb/March 1975) p. 9. Moore, Alan. ‘The Adventures of St. Pancras Panda’. Backstreet Bugle 6 (February 7–19, 1978), 12. Moore, Alan. ‘Yoomin’ cartoon. Backstreet Bugle 13 (May 16–June 5, 1978), 2. Moore, Alan. illustration, NME (October 21, 1978), 27. Moore, Alan. illustration, NME (November 11, 1978), 14. Moore, Alan. ‘St. Pancras Panda gets a dose o’ dat Old Time Religion’, Backstreet Bugle 25 (March 1979), 15. Moore, Alan. 'The Avenging Hunchback'. Dark Star 19 (March 1979), 31. Moore, Alan. 'Kultural Krime Komix'. Dark Star 20 (May 1979), 12. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 263 M. Gray, Alan Moore, Out from the Underground, Palgrave Studies in Comics and Graphic Novels, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-66508-5 264 BIBLIOGRAPHY Vile, Curt. -

Utopia and Dystopia Between Scientific Romance and Graphic Novel

DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE DELLA MEDIAZIONE LINGUISTICA E DI STUDI INTERCULTURALI DOTTORATO IN STUDI LINGUISTICI, LETTERARI E INTERCULTURALI IN AMBITO EUROPEO ED EXTRA-EUROPEO XXIX CICLO “THE END WILL BE THE OVER-MAN”: UTOPIA AND DYSTOPIA BETWEEN SCIENTIFIC ROMANCE AND GRAPHIC NOVEL L-LIN/10 Tesi di dottorato di DANIELE CROCI Tutor: Prof. NICOLETTA VALLORANI Coordinatore del Dottorato: Prof. GIULIANA ELENA GARZONE A.A. 2015/16 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. iii Acknowledgments ...................................................................................................................... v Introduction ............................................................................................................................... vi 1 Utopia, Superhumanity and Modernity in H.G. Wells’s Early Scientific Romances ....... 1 1.1 An Extraordinary Gentleman ........................................................................................ 1 1.2 From the Graphic Novel to the Scientific Romance ..................................................... 4 1.3 The Eutopian Superhuman ............................................................................................ 7 1.4 “The Coming Beast”: Evolution or Ethics in The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds ......................................................................................................................... 11 1.5 Evolution, Science and Society -

How to Make It Rain: a Practical Analysis of Storytelling Forms Mira Singer

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2014 How to Make it Rain: A Practical Analysis of Storytelling Forms Mira Singer Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Singer, Mira, "How to Make it Rain: A Practical Analysis of Storytelling Forms" (2014). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 354. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How to Make it Rain 1 How to Make it Rain A Practical Analysis of Storytelling Forms Mira Singer Independent Program May 2014 Senior Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts degree in the Independent Program. ___________________________________________ Adviser, Nancy Bisaha _________________________________________ Adviser, Don Foster How to Make it Rain 2 Abstract The following is an experiment in practical analysis of storytelling media. The project seeks to explore what insights can be gained about media specificity and adaptation theory through the process of constructing a story and adapting it into background notes, a short story, a one-act play, and a comic book. A meta paper analyzes the constraints and opportunities afforded by each media as observed through the process of creation and adaptation. The historical notes will go last before the paper to facilitate more surprise in the reading experience. There are endnotes classified into H/N (historical note), A/N (author’s note), P/S (primary source), ED/N (editing notes), AD/N (adaptation note), as well as notation marking notes to do with form (F), observations (O), and revelations (R). -

Download Grant Morrison: the Early Years, Timothy Callahan, Sequart

Grant Morrison: The Early Years, Timothy Callahan, Sequart Reaearch & Literacy Organization, 2007, 0615140874, 9780615140872, 263 pages. GRANT MORRISON: THE EARLY YEARS by Timothy Callahan studies the celebrated creatorâÂÂs early career. Grant Morrison has redefined comics from his trailblazing creation of ZENITH, through his metatextual innovations on ANIMAL MAN, to his Dadaist super-heroics in DOOM PATROL. Along the way, he also addressed Batman with his multi-layered masterpiece ARKHAM ASYLUM and the literary GOTHIC storyline. This book examines all five works in detail, drawing out their running and evolving themes. Using plain language, Callahan opens up MorrisonâÂÂs sometimes difficult texts and expands the readerâÂÂs appreciation of their significance, creating a study accessible to both Grant Morrison aficionados and those new to his work. An extended interview with Morrison on his early career rounds out the volume.. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/IFWKVA V for vendetta , Alan Moore, David Lloyd, Steve Whitaker, Siobhan Dodds, 1989, Comics & Graphic Novels, 286 pages. In an alternate future in which Germany wins World War II and Britain becomes a fascist state, a vigilante named "V" tries to free England of its ideological chains.. Grant Morrison Combining the Worlds of Contemporary Comics, Marc Singer, 2012, COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS, 323 pages. One of the most eclectic and distinctive writers currently working in comics, Grant Morrison (b. 1960) brings the auteurist sensibility of alternative comics and graphic novels .... The New American Splendor Anthology , , 1991, Comics & Graphic Novels, 300 pages. -

Vertigo Comics and the British Invasion Isabelle Licari-Guillaume

Transatlantic Exchanges and Cultural Constructs: Vertigo Comics and the British Invasion Isabelle Licari-Guillaume To cite this version: Isabelle Licari-Guillaume. Transatlantic Exchanges and Cultural Constructs: Vertigo Comics and the British Invasion. International Journal of Comic Art, Drexel Hill, 2018, 20 (1), pp. 189-203. hal-02168889 HAL Id: hal-02168889 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02168889 Submitted on 5 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Transatlantic Exchanges and Cultural Constructs: Vertigo Comics and the British Invasion Isabelle Licari-Guillaume Introduction Mainstream US comics, with their emphasis on the superhero genre, are often presented as the epitome of Americanness. Indeed, characters such as Superman (self-styled champion of “truth, justice, and the American way”), Captain America (who was depicted punching Hitler on the cover of Captain America Comics #1 in March 1941) or Wonder Woman (who literally wears the Star-Spangled Banner) have come to symbolize American cultural hegemony in an increasingly globalized world. Despite this strong national anchorage, however, the American tradition did not develop in a vacuum: comics scholars have shown how European productions influenced US creators over the years (Gabilliet, 2005; Labarre, 2017), or how the arrival of manga in the 2000s helped transform the industry (Brienza, 2016). -

Books on the Batman Ian N

Student Research Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2013 Hunting the Dark Knight: Books on the Batman Ian N. Fox [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/3 1 Ian Fox | [email protected] 2013 Book Collection Contest Hunting the Dark Knight: Books on the Batman It began as a joke; a novelty that I thought would go nowhere. One warm summer’s night browsing the internet for no good reason, I stumbled across some book called Batman and Philosophy . I’d just written a paper on the film The Dark Knight but I’d never considered actually investing any time or money in the topic of Batman. Just for the novelty, though, I ordered it. But after reading it I did another basic Google search; I found another Batman book. And then another. And then another. But let’s go back to the beginning. In 2008 I, like millions of others, wandered into a dark cubical room with my father and sister to see The Dark Knight . The 16 year old boy in me thought it was awesome, but thought little more about it until one day when I stumbled upon a blog post by a screenwriter in North Carolina analyzing the film. I even remember the last line to this day; Batman “tried to make Gotham a better place, and failed, in every conceivable way. The Joker wins at the end of The Dark Knight and now it’s Gordon’s dogs who chase him.” Once I read that last line, I was hooked. -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Examining Committee Douglas Barbour, English and Film Studies Brad Bucknell, English and Film Studies William Beard, English and Film Studies Steven Harris, Art and Design Bart Beaty, Communications and Culture, University of Calgary This document is the product of work, support, and love from many people, and so there is no one person I could possibly dedicate it to. I would like to thank my parents, Michael Kidder and Joanna Ussner, for giving me both a love of fantasy and the ability to critique it; Dr. Kirsten Uszkalo for suggesting, years ago, that I do a dissertation on comic books at all; Dr.