Ricardo Spinelli V for VENDETTA: from BOOKS and BOOK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Construção Histórica Na Graphic Novel V for Vendetta: Aspectos Políticos, Sociais E Culturais Na Inglaterra (1982-1988)

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PELOTAS INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA Dissertação A construção histórica na graphic novel V for Vendetta: aspectos políticos, sociais e culturais na Inglaterra (1982-1988). Felipe Radünz Krüger Pelotas, 2014 2 Felipe Radünz Krüger A construção histórica na graphic novel V for Vendetta: aspectos políticos, sociais e culturais na Inglaterra (1982-1988). Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em História da Universidade Federal de Pelotas, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em História. Orientadora: Profª Drª Larissa Patron Chaves Pelotas, 2014 3 4 Felipe Radünz Krüger A construção histórica na graphic novel V for Vendetta: aspectos políticos, sociais e culturais na Inglaterra da década de 1980 Dissertação aprovada, como requisito parcial, para obtenção do grau de Mestre em História, Programa de Pós-Graduação em História, Universidade Federal de Pelotas. Data da Defesa: 11/04/2014 Banca examinadora: Prof. Dr. Larissa Patron Chaves (Orientador) Doutora em História pela Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos Prof. Dr. Arthur Lima de Avila Doutor em História pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Prof. Dr. Nádia da Cruz Senna Doutora em Ciências da Comunicação pela Universidade de São Paulo Prof. Dr. Aristeu Elisandro Machado Lopes Doutor em História pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul 5 Agradecimentos Após o termino da escrita, pensei finalmente ter acabado meu trabalho. Todavia, ao iniciar a formatação do texto, deparei-me com o espaço direcionado aos agradecimentos e comecei automaticamente a lembrar das pessoas responsáveis pela minha formação pessoal e profissional. Após alguns minutos, conclui que por mais que me esforce, não tenho como agradecer a todos os que ajudaram a formar o indivíduo e o historiador que sou hoje. -

Die Wahrheit Liegt Auf Dem Platz

Gratis-Comic von Panini zum 1. internationalen Batman-Tag Fans bekommen den Batman-Comic am 26. September bei allen teilnehmenden Fachhändlern in Deutschland geschenkt Stuttgart, 31. August 2015 – Premiere zu Ehren des Dunklen Rit- ters: Am 26. September lädt DC Entertainment dazu ein, den 1. in- ternationalen Batman-Tag rund um den Globus zu feiern. Panini bietet den Fans als exklusiver DC Comics-Lizenznehmer in Deutschland eine ganze Reihe an Besonderheiten: Alle teilneh- menden Comic-Fachhändler verschenken an diesem Tag einen eigens von Panini produzierten 32-seitigen Batman-Comic. Das Heft wartet mit einer Leseprobe der aktuellen Bestseller- Geschichte „Todesspiel“ (US-Original: „Endgame“) auf. Diese ist von Oktober an in der regulären Batman-Serie nachzulesen. Zu- dem enthält der Sondercomic eine komplette, abgeschlossene Batman-Geschichte – entnommen aus dem Batman Megaband 1. Der Stuttgarter Verlag stellt dem Handel darüber hinaus für den 26. September gratis Papiermasken mit den Motiven Batman, Batman of the Future, Joker und dessen Ex-Geliebte Harley Quinn zur Verfügung. „Nachdem der erste deutschlandweite Panini-Batman-Tag zum 75. Geburtstag der Figur im vergangenen Jahr so erfolgreich war, wollten wir in diesem Jahr noch eine Schippe für die Fans draufle- gen und schließen uns den internationalen Festivitäten an“, sagt Thorsten Kleinheinz von Panini. Panini und DC Comics eint eine ungewöhnlich lange Zeit der ge- schäftlichen Verbundenheit: Bereits seit 2001 veröffentlicht Panini deutsche Versionen der amerikanischen DC- und damit auch Batman-Comics. Der Superheld war von Beginn an das DC- Flaggschiff mit einer eigenen Heftserie, die monatlich bei Panini erscheint. In diesem Jahr gibt es sogar eine zusätzliche zweite Batman-Heftserie mit dem Titel „Batman Eternal“, die aufgrund der großen Nachfrage nach den Geschichten des Dunklen Ritters 14- täglich erscheint. -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

V for Vendetta’: Book and Film

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS “9 into 7” Considerations on ‘V for Vendetta’: Book and Film. Luís Silveiro MESTRADO EM ESTUDOS INGLESES E AMERICANOS (Estudos Norte-Americanos: Cinema e Literatura) 2010 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS “9 into 7” Considerations on ‘V for Vendetta’: Book and Film. Luís Silveiro Dissertação orientada por Doutora Teresa Cid MESTRADO EM ESTUDOS INGLESES E AMERICANOS (Estudos Norte-Americanos: Cinema e Literatura) 2010 Abstract The current work seeks to contrast the book version of Alan Moore and David Lloyd‟s V for Vendetta (1981-1988) with its cinematic counterpart produced by the Wachowski brothers and directed by James McTeigue (2005). This dissertation looks at these two forms of the same enunciation and attempts to analise them both as cultural artifacts that belong to a specific time and place and as pseudo-political manifestos which extemporize to form a plethora of alternative actions and reactions. Whilst the former was written/drawn during the Thatcher years, the film adaptation has claimed the work as a herald for an alternative viewpoint thus pitting the original intent of the book with the sociological events of post 9/11 United States. Taking the original text as a basis for contrast, I have relied also on Professor James Keller‟s work V for Vendetta as Cultural Pastiche with which to enunciate what I consider to be lacunae in the film interpretation and to understand the reasons for the alterations undertaken from the book to the screen version. An attempt has also been made to correlate Alan Moore‟s original influences into the medium of a film made with a completely different political and cultural agenda. -

Overthrowing Vengeance: the Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta

Overthrowing Vengeance: The Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta Pedro Moreira University of Porto, Portugal Citation: Pedro Moreira, ”Overthrowing Vengeance: The Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta ”, Spaces of Utopia: An Electronic Journal , nr. 4, Spring 2007, pp. 106-112 <http://ler.letras.up.pt > ISSN 1646-4729. Introduction The emergence of the critical dystopia genre in the 1980s allowed for the appearance of a body of literature capable of both informing and prompting readers to action. The open-endness of these works, coupled with the sense of critique, becomes a key element in performing a catalyst function and maintaining hope within the text. V for Vendetta , by Alan Moore, with illustrations by David Lloyd, first published in serial form between 1982 and 1988 and, later, in 1990, as a graphic novel is one of such works. Appearing during the political climate of Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government, it became a cult classic amongst graphic novels readers and collectors. A film adaptation was released in 2006, from a screenplay by the Wachowski brothers, to different reactions from the graphic novel’s creators; Moore withdrew his support and denied any involvement in the adaptation while David Lloyd publicly confessed his admiration for the movie. I first became interested in the series due to its gritty realism, and the enigmatic, cultured figure of the protagonist. In fact, V for Vendetta ’s universe is quite distant from the comic book genre, which is dominated by God-like figures such as Superman or Spiderman. Also, the sheer scope of reference in the work, ranging from Blake and Shakespeare to the Rolling Stones and The Velvet Underground, added to my interest, making it the subject of this paper. -

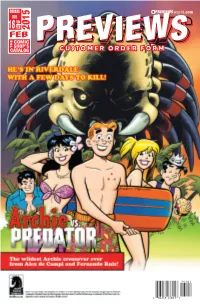

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

Alan Moore V for Vendetta

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons Early draft of essay eventually published in Sexual Ideology in the Works of Alan Moore Comer 1 “Body Politics: Unearthing an Embodied Ethics in V for Vendetta” Todd A. Comer In light of the oft-made allegation that superheroes are in many respects carbon copies of the fascist world that they were consciously or unconsciously intended to oppose, V for Vendetta may be Alan Moore’s most direct commentary on the superheroic body and its desires. Intimations of fascism, of course, are everywhere in Moore’s work. The German soldier who shatters Alice’s mirror in Lost Girls, William Gull’s bird-like transcendence in From Hell, Superman’s repression of the too-earthy Swamp Thing in “The Jungle Line,” Moriarty’s cavorite- fueled journey toward heaven (and death) in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen—all speak to Moore’s critique of the superheroic tendency to marginalize the world and others. Moore and David Lloyd’s graphic novel is the most direct commentary on the superhero body if only because the body of the hero and villain are obnoxiously present, even as they strangely absent themselves. The novel appears to ground agency to an embodied totalitarian world in terms of (dis)embodiment. Agency is, of course, an issue of the body and its representation, but Moore and Lloyd get it wrong, at least on one overt level, by misunderstanding the ultimate goal of fascism and reproducing a notion of agency that merely reproduces on another level the (ontological) state that it presumes to counter. -

Absolute Swamp Thing by Alan Moore Volume 2 Ebook, Epub

ABSOLUTE SWAMP THING BY ALAN MOORE VOLUME 2 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alan Moore | 464 pages | 27 Oct 2020 | DC Comics | 9781779502827 | English | United States Absolute Swamp Thing by Alan Moore Volume 2 PDF Book Bissette , John Totleben , Various. Taking off from the end of Brightest Day , the series follows a resurrected Alec Holland who wants to put the memories of the Swamp Thing behind him. The supplemental material for this volume is reprinted from the limited edition Watchmen hardcover published by Graphitti Designs in Marshall McCune rated it really liked it Jan 31, Add to Watchdog. He never will be Alec Holland. Release date: TBA. Alan Moore is an English writer most famous for his influential work in comics, including the acclaimed graphic novels Watchmen, V for Vendetta and From Hell. Released on December 7, Arcane returns and arranges an abduction of Abby to force Tefe to use her powers to grow him a healthy body. Satyajit Chetri rated it really liked it Nov 16, Geraldine Viswanathan and Dacre Montgomery star in this romantic comedy written and directed by Natalie Krinsky. Hendrik rated it it was amazing Oct 24, Gabriel Morato rated it really liked it Oct 18, After the completion of this storyline, the Swamp Thing sought to resolve his need for vengeance against those who had "killed" him during his showdown in Gotham City, culminating in a showdown with Lex Luthor and Superman in Swamp Thing vol. Moore resides in central England. Jamie Delano. Currently out of print. Shop Now. The Swamp Thing would not appear again until Mike Carey 's run on Hellblazer in issues — and —, leading into the fourth Swamp Thing series. -

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons's Watchmen

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators Reading Questions: Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons's Watchmen 1. What different themes does this book explore? Be as detailed and exhaustive as possible. 2. Pick a panel and analyze how Moore and Gibbons combine text and visuals to their utmost effect. 3. Pick a page and analyze its overall layout. How does the page as a whole make use of the comic book format to achieve meaning and impact. You might find it helpful to consider the larger themes of Watchmen. 4. Visual motifs are recurrent images that take on specific meanings relevant to a given work. What visual motifs appear throughout Watchmen and what meanings do they suggest? 5. How does the issue of crimefighting evolve over time in the world imagined in Watchmen? 6. Consider the names "Rorschach" and "Ozymandias." Why are these particularly appropriate names for these two characters? 7. Which character or characters do you sympathize with most? Why? 8. What does Chapter IV, "Watchmaker," reveal to us about Dr. Manhattan? How does he experience time? What are his interests? How would you summarize his view of existence? 9. How do Moore and Gibbons use the imagined history in Watchmen to comment on real events in 20th century America? 10. Look closely at Chapter V, "Fearful Symmetry." How does the idea of "symmetry" play out in this chapter in both form and content? 11. What are the worldviews of Dr. Manhattan, Rorschach, and Adrian Veidt? Where do these worldviews intersect? Where do they differ? 12. What does Watchmen suggest about masked crimefighters and their costumes? Which characters bring these ideas most clearly into focus? 13. -

Psychogeography in Alan Moore's from Hell

English History as Jack the Ripper Tells It: Psychogeography in Alan Moore’s From Hell Ann Tso (McMaster University, Canada) The Literary London Journal, Volume 15 Number 1 (Spring 2018) Abstract: Psychogeography is a visionary, speculative way of knowing. From Hell (2006), I argue, is a work of psychogeography, whereby Alan Moore re-imagines Jack the Ripper in tandem with nineteenth-century London. Moore here portrays the Ripper as a psychogeographer who thinks and speaks in a mystical fashion: as psychogeographer, Gull the Ripper envisions a divine and as such sacrosanct Englishness, but Moore, assuming the Ripper’s perspective, parodies and so subverts it. In the Ripper’s voice, Moore emphasises that psychogeography is personal rather than universal; Moore needs only to foreground the Ripper’s idiosyncrasies as an individual to disassemble the Grand Narrative of English heritage. Keywords: Alan Moore, From Hell, Jack the Ripper, Psychogeography, Englishness and Heritage ‘Hyper-visual’, ‘hyper-descriptive’—‘graphic’, in a word, the graphic novel is a medium to overwhelm the senses (see Di Liddo 2009: 17). Alan Moore’s From Hell confounds our sense of time, even, in that it conjures up a nineteenth-century London that has the cultural ambience of the eighteenth century. The author in question is wont to include ‘visual quotations’ (Di Liddo 2009: 450) of eighteenth- century cultural artifacts such as William Hogarth’s The Reward of Cruelty (see From Hell, Chapter Nine). His anti-hero, Jack the Ripper, is also one to flaunt his erudition in matters of the long eighteenth century, from its literati—William Blake, Alexander Pope, and Daniel Defoe—to its architectural ideal, which the works of Nicholas Hawksmoor supposedly exemplify. -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats.