An Assessment of Invasive Species Management in Idaho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition AKA exotic, alien, non-native, introduced, non-indigenous, or foreign sp. National Invasive Species Council definition: (1) “a non-native (alien) to the ecosystem” (2) “a species likely to cause economic or harm to human health or environment” Not all invasive species are foreign origin (Spartina, bullfrog) Not all foreign species are invasive (Most US ag species are not native) Definition increasingly includes exotic diseases (West Nile virus, anthrax etc.) Can include genetically modified/ engineered and transgenic organisms Executive Order 13112 (1999) Directed Federal agencies to make IS a priority, and: “Identify any actions which could affect the status of invasive species; use their respective programs & authorities to prevent introductions; detect & respond rapidly to invasions; monitor populations restore native species & habitats in invaded ecosystems conduct research; and promote public education.” Not authorize, fund, or carry out actions that cause/promote IS intro/spread Political, Social, Habitat, Ecological, Environmental, Economic, Health, Trade & Commerce, & Climate Change Considerations Historical Perspective Native Americans – Early explorers – Plant explorers in Europe Pioneers moving across the US Food - Plants – Stored products – Crops – renegade seed Animals – Insects – ants, slugs Travelers – gardeners exchanging plants with friends Invasive Species… …can also be moved by • Household goods • Vehicles -

Abacca Mosaic Virus

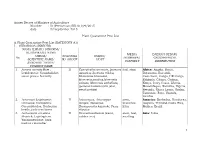

Annex Decree of Ministry of Agriculture Number : 51/Permentan/KR.010/9/2015 date : 23 September 2015 Plant Quarantine Pest List A. Plant Quarantine Pest List (KATEGORY A1) I. SERANGGA (INSECTS) NAMA ILMIAH/ SINONIM/ KLASIFIKASI/ NAMA MEDIA DAERAH SEBAR/ UMUM/ GOLONGA INANG/ No PEMBAWA/ GEOGRAPHICAL SCIENTIFIC NAME/ N/ GROUP HOST PATHWAY DISTRIBUTION SYNONIM/ TAXON/ COMMON NAME 1. Acraea acerata Hew.; II Convolvulus arvensis, Ipomoea leaf, stem Africa: Angola, Benin, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae; aquatica, Ipomoea triloba, Botswana, Burundi, sweet potato butterfly Merremiae bracteata, Cameroon, Congo, DR Congo, Merremia pacifica,Merremia Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, peltata, Merremia umbellata, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Ipomoea batatas (ubi jalar, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, sweet potato) Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo. Uganda, Zambia 2. Ac rocinus longimanus II Artocarpus, Artocarpus stem, America: Barbados, Honduras, Linnaeus; Coleoptera: integra, Moraceae, branches, Guyana, Trinidad,Costa Rica, Cerambycidae; Herlequin Broussonetia kazinoki, Ficus litter Mexico, Brazil beetle, jack-tree borer elastica 3. Aetherastis circulata II Hevea brasiliensis (karet, stem, leaf, Asia: India Meyrick; Lepidoptera: rubber tree) seedling Yponomeutidae; bark feeding caterpillar 1 4. Agrilus mali Matsumura; II Malus domestica (apel, apple) buds, stem, Asia: China, Korea DPR (North Coleoptera: Buprestidae; seedling, Korea), Republic of Korea apple borer, apple rhizome (South Korea) buprestid Europe: Russia 5. Agrilus planipennis II Fraxinus americana, -

Rules Governing Invasive Species and Noxious Weeds

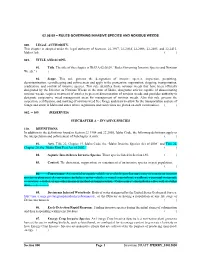

02.06.09 – RULES GOVERNING INVASIVE SPECIES AND NOXIOUS WEEDS 000. LEGAL AUTHORITY. This chapter is adopted under the legal authority of Sections, 22-1907, 22-2004, 22-2006, 22-2403, and 22-2412, Idaho Code. ( ) 001. TITLE AND SCOPE. 01. Title. The title of this chapter is IDAPA 02.06.09, “Rules Governing Invasive Species and Noxious Weeds.” ( ) 02. Scope. This rule governs the designation of invasive species, inspection, permitting, decontamination, recordkeeping and enforcement and apply to the possession, importation, shipping, transportation, eradication, and control of invasive species. This rule identifies those noxious weeds that have been officially designated by the Director as Noxious Weeds in the state of Idaho, designates articles capable of disseminating noxious weeds, requires treatment of articles to prevent dissemination of noxious weeds and provides authority to designate cooperative weed management areas for management of noxious weeds. Also this rule governs the inspection, certification, and marking of noxious weed free forage and straw to allow for the transportation and use of forage and straw in Idaho and states where regulations and restrictions are placed on such commodities. ( ) 002. -- 109. (RESERVED) SUBCHAPTER A – INVASIVE SPECIES 110. DEFINITIONS. In addition to the definitions found in Section 22-1904 and 22-2005, Idaho Code, the following definitions apply in the interpretation and enforcement of Subchapter A only: ( ) 01. Acts. Title 22, Chapter 19, Idaho Code, the “Idaho Invasive Species Act of 2008” and Title 22, Chapter 20, the “Idaho Plant Pest Act of 2002.” ( ) 02. Aquatic Invertebrate Invasive Species. Those species listed in Section 140. ( ) 03. Control. The abatement, suppression, or containment of an invasive species or pest population. -

Micro-Moth Grading Guidelines (Scotland) Abhnumber Code

Micro-moth Grading Guidelines (Scotland) Scottish Adult Mine Case ABHNumber Code Species Vernacular List Grade Grade Grade Comment 1.001 1 Micropterix tunbergella 1 1.002 2 Micropterix mansuetella Yes 1 1.003 3 Micropterix aureatella Yes 1 1.004 4 Micropterix aruncella Yes 2 1.005 5 Micropterix calthella Yes 2 2.001 6 Dyseriocrania subpurpurella Yes 2 A Confusion with fly mines 2.002 7 Paracrania chrysolepidella 3 A 2.003 8 Eriocrania unimaculella Yes 2 R Easier if larva present 2.004 9 Eriocrania sparrmannella Yes 2 A 2.005 10 Eriocrania salopiella Yes 2 R Easier if larva present 2.006 11 Eriocrania cicatricella Yes 4 R Easier if larva present 2.007 13 Eriocrania semipurpurella Yes 4 R Easier if larva present 2.008 12 Eriocrania sangii Yes 4 R Easier if larva present 4.001 118 Enteucha acetosae 0 A 4.002 116 Stigmella lapponica 0 L 4.003 117 Stigmella confusella 0 L 4.004 90 Stigmella tiliae 0 A 4.005 110 Stigmella betulicola 0 L 4.006 113 Stigmella sakhalinella 0 L 4.007 112 Stigmella luteella 0 L 4.008 114 Stigmella glutinosae 0 L Examination of larva essential 4.009 115 Stigmella alnetella 0 L Examination of larva essential 4.010 111 Stigmella microtheriella Yes 0 L 4.011 109 Stigmella prunetorum 0 L 4.012 102 Stigmella aceris 0 A 4.013 97 Stigmella malella Apple Pigmy 0 L 4.014 98 Stigmella catharticella 0 A 4.015 92 Stigmella anomalella Rose Leaf Miner 0 L 4.016 94 Stigmella spinosissimae 0 R 4.017 93 Stigmella centifoliella 0 R 4.018 80 Stigmella ulmivora 0 L Exit-hole must be shown or larval colour 4.019 95 Stigmella viscerella -

Danske Snyltehvepse Og -Fluer Fra Fyrrevikleren, Rhyacionia Buoliana Schiff

Danske snyltehvepse og -fluer fra fyrrevikleren, Rhyacionia buoliana Schiff. (Lepid., Tortricidaey af PETER ESBJERG (With a summary: Danish hymenopterous and dipterous parasites from the pine shoot moth, Rhyacionia buoliana Schiff.). Fyrrevikleren er på grund af sin forstlige betydning blevet fulgt med be tydelig interesse i Europa de senere år. Også i Danmark har den været genstand for øget opmærksomhed, hvad især hænger sammen med den stigende anvendelse af contortafyr (Pinus contorta Loud.) i dansk skov brug (B. Bejer-Petersen, 1966 ). Contortafyrren kan nemlig angribes meget stærkt, da den hører til blandt fyrreviklerens foretrukne værtstræer. Deri mod finder man her i landet sjældent større angreb på andre fyrretræer (Esbjerg og Feilberg, 1970). De fleste udenlandske undersøgelser har vist, at fyrrevikleren ofte er udsat for en ikke ringe parasitering af en række snyltehvepse og -fluer. Naturlige spørgsmål angående det hjemlige fyrreviklerproblem har derfor været, om vor fyrreviklerbestand også parasiteres, og i bekræftende fald da i hvilket omfang, og om parasitterne er de samme som i nabolandene. Undersøgelsen heraf er begrænset til contortafyr med udeladelse af æg• parasitter, der antagelig kun findes i ringe antal. MATERlAL E OG METODIK Indsamling Indsamlingerne er foretaget i juni måned, da de angrebne skud på denne tid er særlig lette at erkende, og klækningen er nært forestående. I materialet indgår 15 lokaliteter, der repræsenterer fyrreviklerangreb af varierende tæthed og styrke, i aldrene 1-1 O år (tabel 1 og fig. 1). Prø verne udtoges systematisk efter groftmasket kvadratnet i årene 1969-70 og for et enkelt områdes vedkommende også i 1968. Der indsamledes ialt ca. 9000 skud. -

Pinus Nigra V

Technical guidelines for genetic conservation and use European black pine Pinus nigra V. Isajev1, B. Fady2, H. Semerci3 and V. Andonovski4 1 Forestry Faculty of Belgrade University, Belgrade, Serbia and Montenegro EUFORGEN 2 INRA, Mediterranean Forest Research Unit, Avignon, France 3 Forest Tree Seeds&Tree Breeding Research Directorate, Ankara,Turkey 4 Faculty of Forestry, Skopje, Macedonia FYR These Technical Guidelines are intended to assist those who cherish the valuable European black pine genepool and its inheritance, through conserving valuable seed sources or use in practical forestry. The focus is on conserving the genetic diversity of the species at the European scale. The recommendations provided in this module should be regarded as a commonly agreed basis to be complemented and further developed in local, national or regional conditions. The Guidelines are based on the available knowledge of the species and on widely accepted methods for the conservation of forest genetic resources. Biology and ecology although seed yield is abundant only every 2–4 years. Trees reach sexual maturity at 15–20 years in The European black pine (Pinus their natural habitat. Flowers nigra Arnold) grows up to 30 appear in May. Female inflores- (rarely 40–50) m tall, with a trunk cences are reddish, and male that is usually straight. The bark catkins are yellow. Fecundation is light grey to dark grey-brown, occurs 13 months after pollina- deeply furrowed longitudinally on tion. Cones are sessile and hori- older trees. The crown is broadly zontally spreading, 4–8 cm long, conical on young trees, umbrel- 2–4 cm wide, yellow-brown or la-shaped on older trees, light yellow and glossy. -

Asparagus Pests and Diseases by Joan Allen

Asparagus Pests and Diseases By Joan Allen Asparagus is one of the few perennial vegetables and with good care a planting can produce a nice crop for 10-15 years. Part of that good care is keeping pest and disease problems under control. Letting them go can lead to weak plants and poor production, even death of the plants in some cases. Stress due to poor nutrition, drought or other problems can make the plants more susceptible to some diseases too. Because of this, good cultural practices, including a good site for new plantings, are the first step in preventing problems. After that, monitor regularly for common pests and diseases so you can catch any problems early and hopefully prevent them from escalating. Weed control is important for a couple of reasons. One, weeds compete with the crop for water and nutrients. More importantly from a disease perspective, they reduce air flow around the plants or between rows and this results in the asparagus spears or foliage remaining wet for a longer period of time after a rain or irrigation event. This matters because moisture promotes many plant diseases. This article will cover some of the most common pests and diseases of asparagus. If you’re not sure what you’ve got, I’ll finish up with resources for assistance. Insect pests include the common and spotted asparagus beetles, asparagus aphid, cutworms, and Japanese beetles. Diseases that will be covered are Fusarium diseases, rust, and purple spot. Both the common and spotted asparagus beetles (CAB and SAB respectively) overwinter in brushy or wooded areas near the field or garden as adults. -

1. Cherry Bark Tortrix (CBT), Cherry Washington. Thetrees Have

III. Stone Fruits a. Biology 1. Cherry Bark Tortrix (CBT), cherry Michael W. Klaus Washington State Department ofAgriculture 2015 S. First Street Yakima, WA 98903 Thefirst U.S. detection of CBT was reported by WSDA on March 29,1991. The find wasa larval collection from an ornamental cherry treeat the PeaceArch StatePark, Blaine, Whatcom County, Washington. Thetrees have extensive tunneling throughout the bark of thetrunk andthe bark ofthe larger limbs. The tunneling has nearly girdled thetrees. Park gardeners consider these sixty yearold Mt. Fuji cherry trees to bea total loss andwill be removing them soon. The cherry bark tortrix (CBT), Enarmonia formosana (Scopoli), isnative to Europe and Siberia. Itwas first mentioned as a pestofstonefruits in Europe by Kollar in 1837 andas a pest in the British Isles byTheobald (1909). CBT has been reported tocause serious damage in stone fruit, apple, pearand other trees(Thomsen 1920, Samal 1926). CBT issometimes locally serious, but is generally considered tobe a pest of minor importance in the British Isles (Massee,1954). Biology and Identification CBT feeds on the bark and sapwood ofa variety ofplants ofthe family Rosaceaeincluding Prunus (cherry, plum, peach, apricot, nectarine and almond), Malus (apple), Pvrus (pear), Pyracantha (firethom), Sorbus(mountain ash) and Cvdonia (quince). Infested hosts identified in Washington to date (via larval collections, voucher specimens in WSDA Yakima collection) havebeen mature cherryand apple trees. A CBT infestation of mountain ash inVancouver, B.C. Canadawas reported in June of 1992. CBT is a moth in the family Tortricidae. It is related to another important tortricid applepest, the codling moth. Codling moth was once named Enarmonia pomonella. -

Coleoptera) (Excluding Anthribidae

A FAUNAL SURVEY AND ZOOGEOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF THE CURCULIONOIDEA (COLEOPTERA) (EXCLUDING ANTHRIBIDAE, PLATPODINAE. AND SCOLYTINAE) OF THE LOWER RIO GRANDE VALLEY OF TEXAS A Thesis TAMI ANNE CARLOW Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 1997 Major Subject; Entomology A FAUNAL SURVEY AND ZOOGEOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS OF THE CURCVLIONOIDEA (COLEOPTERA) (EXCLUDING ANTHRIBIDAE, PLATYPODINAE. AND SCOLYTINAE) OF THE LOWER RIO GRANDE VALLEY OF TEXAS A Thesis by TAMI ANNE CARLOW Submitted to Texas AgcM University in partial fulltllment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Approved as to style and content by: Horace R. Burke (Chair of Committee) James B. Woolley ay, Frisbie (Member) (Head of Department) Gilbert L. Schroeter (Member) August 1997 Major Subject: Entomology A Faunal Survey and Zoogeographic Analysis of the Curculionoidea (Coleoptera) (Excluding Anthribidae, Platypodinae, and Scolytinae) of the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. (August 1997) Tami Anne Carlow. B.S. , Cornell University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Horace R. Burke An annotated list of the Curculionoidea (Coleoptem) (excluding Anthribidae, Platypodinae, and Scolytinae) is presented for the Lower Rio Grande Valley (LRGV) of Texas. The list includes species that occur in Cameron, Hidalgo, Starr, and Wigacy counties. Each of the 23S species in 97 genera is tteated according to its geographical range. Lower Rio Grande distribution, seasonal activity, plant associations, and biology. The taxonomic atTangement follows O' Brien &, Wibmer (I og2). A table of the species occuning in patxicular areas of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, such as the Boca Chica Beach area, the Sabal Palm Grove Sanctuary, Bentsen-Rio Grande State Park, and the Falcon Dam area is included. -

Data Sheets on Quarantine Pests

EPPO quarantine pest Prepared by CABI and EPPO for the EU under Contract 90/399003 Data Sheets on Quarantine Pests Cydia prunivora IDENTITY Name: Cydia prunivora (Walsh) Synonyms: Grapholitha prunivora (Walsh) Enarmonia prunivora Walsh Semasia prunivora Walsh Laspeyresia prunivora Walsh Taxonomic position: Insecta: Lepidoptera: Tortricidae Common names: Lesser appleworm, plum moth (English) Petite pyrale (French) Bayer computer code: LASPPR EPPO A1 list: No. 36 EU Annex designation: II/A1 - as Enarmonia prunivora HOSTS The main natural host is Crataegus spp., especially the larger-fruited species such as C. holmesiana. C. prunivora readily attacks apples, plums and cherries. It has been recorded on peaches, roses and Photinia spp. Larvae may also develop in galls of Quercus and Ulmus. For more information, see Chapman & Lienk (1971). GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION C. prunivora is indigenous on wild Crataegus spp. in eastern North America (north-eastern states of USA and adjoining provinces of Canada) and has spread onto fruit trees in other parts of North America (western Canada and USA). EPPO region: Absent. Asia: China (Heilongjiang only, unconfirmed). The record given for India in the previous edition is erroneous. North America: Canada (British Columbia, eastern provinces), USA (practically throughout). EU: Absent. Distribution map: See CIE (1975, No. 341). BIOLOGY The life and seasonal history is similar to that of the European codling moth, Cydia pomonella. C. prunivora overwinters as a full-grown larva in a cocoon in debris on the ground or in crevices in the trunks of host trees. In the western fruit district of New York State, USA, and in Ontario, Canada, pupation takes place in May and lasts 2-3 weeks. -

Cecidophyopsis Ribis Westw.)

Danish Research Service for Plant and Soil Science Report no. 1880 Research Centre for Plant Proteetion Institute of Pesticides D K-2800 Lyngby Chemicais test e d in the laboratory for the control of ofblack currant gall mite (Cecidophyopsis ribis Westw.) Afprøvning i laboratoriet af bekæmpelsesmidlers virkning mod solbærknopgalmider (Cecidophyopsis ribis Westw.) Steen ~kke Nielsen Summary 32 chemicals were teste d in the laboratory against the black currant gall mite (Cecidophyopsis ribis Westw.). Only 5 chemicals showed an acceptable controlling effect. They were endosulfan, oxamyl, avermectin, lime sulphur and wettable sulphur. 8 pyrethroids, 3 other insecticides and 8 acaricides were all ineffective and the same applied to 8 fun gicides normally used against diseases in black currants. Key words: Chemicals, laboratory test, black currant gal! mite, Cecidophyopsis ribis Westw. Resume 32 pesticider blev afprøvet i laboratoriet for deres virkning mod solbærknopgalmider (Cecidophyopsis ribis Westw.). Kun 5 midler gaven tilfredsstillende virkning. Det var endosulfan, oxamyl, avermectin, svovlkalk og sprøjtesvovl. 8 pyrethroider, 3 andre insekticider og 8 acaricider havde ingen eller en util strækkelig virkning mod solbærknopgalmiderne. Det samme gjaldt for 8 fungicider, der er almindeligt benyttet til bekæmpelse af svampesygdomme i solbær. Nøgleord: Pesticider, laboratorie-test, solbærknopgalmider, Cecidophyopsis ribis Westw. Introduction ternatives. Different types of chemicals were cho The most serious pest in black currants in Den sen to be tested for their con tro Iling effect on the mark is the black currant gall mite. Black currants gall mite: Pyrethroids because of their low mam are a rather small crop, so little effort has been malian toxicity and their repellent action against made to find suitable chemicals to control the gall honeybees; acaricides with harvest intervals of 4 mite. -

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, USDA § 319.56–22

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, USDA § 319.56–22 is free of fruit flies must be treated for Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, such pests in accordance with part 305 South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Wash- of this chapter. If an authorized treat- ington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyo- ment does not exist for a specific fruit ming, the District of Columbia, or the fly, the importation of such apples and U.S. Virgin Islands, or any part of Illi- pears is prohibited. nois, Kentucky, Missouri, or Virginia, north of the 38th parallel, subject to § 319.56–21 Okra from certain coun- the requirements of § 319.56–3. tries. (d) Importations into areas of California Okra from Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, that are not pink bollworm generally in- Guyana, Mexico, Peru, Suriname, Ven- fested or suppressive areas. (1) During ezuela, and the West Indies may be im- January 1 through March 15, inclusive, ported into the United States in ac- okra may be imported into California cordance with this section and all subject to the requirements of § 319.56– other applicable provisions of this sub- 3. part. (2) During March 16 through Decem- (a) Importations into pink bollworm ber 31, inclusive, okra may be imported generally infested or suppressive areas in into California if it is treated for the the United States. Okra may be im- pink bollworm in accordance with part ported into areas defined in § 301.52–2a 305 of this chapter. as pink bollworm generally infested or (e) Imports from Andros Island of the suppressive areas, provided the okra is Bahamas.