Midnight Man Katherine Strine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States' Janus-Faced Approach to Operation Condor: Implications for the Southern Cone in 1976

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2008 The United States' Janus-Faced Approach to Operation Condor: Implications for the Southern Cone in 1976 Emily R. Steffan University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Steffan, Emily R., "The United States' Janus-Faced Approach to Operation Condor: Implications for the Southern Cone in 1976" (2008). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1235 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emily Steffan The United States' Janus-Faced Approach To Operation Condor: Implications For The Southern Cone in 1976 Emily Steffan Honors Senior Project 5 May 2008 1 Martin Almada, a prominent educator and outspoken critic of the repressive regime of President Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay, was arrested at his home in 1974 by the Paraguayan secret police and disappeared for the next three years. He was charged with being a "terrorist" and a communist sympathizer and was brutally tortured and imprisoned in a concentration camp.l During one of his most brutal torture sessions, his torturers telephoned his 33-year-old wife and made her listen to her husband's agonizing screams. -

Read Book DC Halloween Collection

DC HALLOWEEN COLLECTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tim Seeley | 160 pages | 08 Oct 2019 | DC Comics | 9781401294472 | English | United States DC Halloween Collection PDF Book Feb 03, Troy rated it it was amazing. Introduced January Superman: Last Son of Krypton. Nick Cutter Goodreads Author ,. See all 6 - All listings for this product. And that zombie Justice League story! Click here for calendar of events. Howard Chaykin Illustrator ,. The dialogue is kinda dumb at times but other than that a really fun one. Meanwhile, a certain District Attorney named Harvey Dent is also on the case and has a date with destiny Nov 10, Sesana rated it liked it Shelves: comics , superhumans , short-stories. Vita Ayala Goodreads Author ,. Giffen is known for having an unorthodox writing style, often using characters in ways not seen before. JLA Earth 2. The other stories were nice, short Halloween reads and were much more what I was expecting. Lists with This Book. Yeah, it was alright. Ronald Malfi Goodreads Author ,. A great addition for DC Comics fans, or as an addition to your Halloween A couple of stories were rather light-hearted such as the Zatanna yarn in which her and Fables' Bill Willingham show a scared little girl the magic behind Halloween. Some stories will scare you, others will delight, all are spook-tacular fun! Volume 22 DC Comics Trinity. Nov 03, tony dillard jr rated it really liked it. Volume 12 Lex Luthor: Man of Steel. If you can trust anyone to protect your sweet treats, it's the Amazon Princess. This wiki. From the outside, you can't even tell it's makeup, as Hot Topic did such a good job of recreating the Handbook for the Recently Deceased book from the cult-classic film starring Winona Ryder. -

Midnight Man 10-31-07

T H E M I D N I G H T M A N by PATRICK MELTON & MARCUS DUNSTAN 10-31-07 FADE INTO: 1 EXT. GATED COMMUNITY - NIGHT 1 PUSH THROUGH the outside gates, entering an upper-middle class gated community, passing a YOUNG SECURITY GUARD sitting in the GUARD STAND. The front lawns are perfectly groomed. Decorative lamps light the streets. The homes are spacious. All similarly designed. Then, the SOUND of ADULTS GIGGLING creeps in. Sexily. Perhaps a little tipsy. MALE VOICE (V.O.) Ahhhhh...damn it. The power's out. FEMALE VOICE (V.O.) The rest of the block is on... MALE VOICE (V.O.) Nah, it's the workers. They just blew another fucking fuse. An exasperated laugh from the female. FEMALE VOICE (V.O.) At least candles are romantic. MALE VOICE (V.O.) You know, if they had to work past sunset this would never happen. (beat) Can you check the box? FEMALE VOICE (V.O.) Babe, I'm in heels. ONE HOUSE stands out. It's in a cul-de-sac, and it's being refurbished: materials, work boxes, and port-o-potty on the lawn. The lights are all out. MALE VOICE (V.O.) Yeah, well, I'm in-toxicated. The Female Voice lets out a playful GIGGLE. And-- 2 INT. SUBURBAN HOME - FRONT FOYER - NIGHT 2 CLOSE ON: A SPIDER gazes from the corner of its CEILING WEB. A sexy woman in an evening dress slinks up some STAIRS looking back with a mischievous smile. This is GENA WHARTON (30s). 2. -

The Story of Israel at 66 Through the Songs of Arik Einstein

1 The Soundtrack of Israel: The Story of Israel at 66 through the songs of Arik Einstein Israel turns sixty six this year and a so much has happened in this seemingly short lifetime. Every war, every peace treaty, every struggle, and every accomplishment has left its impact on the ever changing character of the Jewish State. But throughout all of these ups and downs, all of the conflicts and all of the progress, there has been one voice that has consistently spoken for the Jewish nation, one voice that has represented Israelis for all 66 years and will continue to represent a people far into the future. That is the voice of Arik Einstein. Einstein’s music, referred to by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as the “soundtrack of Israel,” transcended generations. Einstein often took the words of high-brow Israeli poets such as Chaim Nachman Bialik, Rahel, Nathan Alterman and Avraham Halfi and turned them into rock anthems sung by vibrant Israeli youth. Einstein captured the heart and soul of Israelis old and young. For every Zionist, peacenik, settler, hopeless romantic, nostalgia aficionado and child (or child at heart) in Israel, there is at least one Arik Einstein song that speaks to them. For every historic Israeli moment, there is an Arik Einstein song that represents the emotion of a united nation, or a shuttered people. Although fairly unknown outside of Israel, Arik Einstein was loved by all, and mourned by all after his sudden death in November of 2013, when tens of thousands of Israelis joined together to pay their respects to the iconic Sabra at a memorial service in Rabin Square in Tel Aviv. -

Songleading Major Chord Supplement & Resources

Kutz Camp 2011 Songleading Major Chord Supplement & Resources Compiled by Max Chaiken and Debra Winter [email protected] [email protected] - Kutz Camp Songleading Track 2011 RESOURCES! Compiled with love by Max and Deb Transcontinental Music, Music Publishing branch of the URJ: httllJ/www.transcontinentalm_y_~c.~Qm/home,ghP. Shireinu Complete: htt12J/www.transcontinentalmusic.com/grodu~t.Qh:t!?productid=441 Shireinu Chordster: httg: //www.transcontinentalmusic.com /groduct.phQ ?productid=17 4 2 OySongs, www.oysongs.com -Jewish music downloads, sheet music downloads, and a Jewish-only version of iTunes! Jewish Rock Radio, www.jewishrockradio.com, featuring live streaming radio of American and Israeli Jewish rock and contemporary music, as well as links to artists Hava Nashira, httQ.;.//ot006.urj.net/, "A Jewish Songleaders Resource," featuring chord sheets, information about copyright law, and a plethora of links! Hebrew Songs, www.hebrewsongs.com, A database of Israeli songs and lyrics with translation! Rise Up Singing, bttpJJ_www.singout.org/rus.html , Folk song anthology with hundreds of well-known folk songs for groups to sing! Jewish Guitar Chords, http://jewishguitarchords.com/, A new-ish website with a lot of Conservative and Orthodox Jewish artists' chords! Musicians' Pages: Peter & Ellen Allard, http://peterandellen.com/ -specializing in Jewish children's music! Max Chaiken, http: //www.maxchaiken.com -yours truly© Debbie Friedman, z"l, http_J/www.debbiefriedman.com/ httg://www.youtube.com/user/rememberingdebbie Noam Katz, -

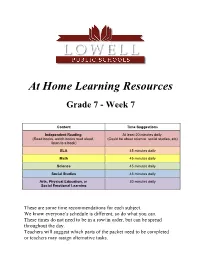

Week 7 Packet

At Home Learning Resources Grade 7 - Week 7 Content Time Suggestions Independent Reading At least 20 minutes daily (Read books, watch books read aloud, (Could be about science, social studies, etc) listen to a book) ELA 45 minutes daily Math 45 minutes daily Science 45 minutes daily Social Studies 45 minutes daily Arts, Physical Education, or 30 minutes daily Social Emotional Learning These are some time recommendations for each subject. We know everyone’s schedule is different, so do what you can. These times do not need to be in a row/in order, but can be spread throughout the day. Teachers will suggest which parts of the packet need to be completed or teachers may assign alternative tasks. Grade 7 ELA Week 7 Your child can complete any of the activities in weeks 1-6. These can be found on the Lowell Public Schools website: https://www.lowell.k12.ma.us/Page/3803 This week begins a focus on memoir reading and writing. Your child should be reading, writing, talking and writing about reading, and exploring new vocabulary each week. Reading: Students need to read each day. They can read the memoir included in this packet and/or read any of the memoir books that they have at home, or can access online at Epic Books, Tumblebooks, the Pollard Library online, or other online books. All resources are on the LPS website. There is something for everyone. Talking and Writing about Reading: As students are reading, they can think about their reading, then talk about their reading with a family member and/or write about their reading using the prompts/questions included. -

"Superman" by Wesley Strick

r "SUPERMAN" Screenplay by Wesley Strick Jon Peters Entertainment Director: Tim Burton Warner Bros. Pictures July 7, 1997 y?5^v First Draft The SCREEN is BLACK. FADE IN ON: INT. UNIVERSITY CORRIDOR - LATE NIGHT A YOUNG PROFESSOR hurries down the empty hall — hotly murmuring to himself, intensely concerned ... A handsome man, about 30, but dressed strangely — are we in some other country? Sometime in the past? Or in the future? YOUNG PROFESSOR It's switched off ... It can't be ... But the readings, what else — The Young Professor reaches a massive steel door, like the hatch of a walk-in safe. Slides an ID card, that's emblazoned with a familiar-looking "S" shield: the door hinges open. The Young Professor pauses — he hadn't noted, till now, the depths of his fear. Then, enters: INT. UNIVERSITY LAB - LATE NIGHT Dark. The Professor tries the lights. Power is off. Cursing, he's got just enough time, as the safe door r swings closed again, to find an emergency flashlight. He flicks it on: plays the beam over all the bizarre equipment, the ultra-advanced science paraphernalia. Now he hears a CREAK. He spins. His voice quavers. YOUNG PROFESSOR I.A.C. ..? His flashlight finds a thing: a translucent ball perched atop a corroding pyramid shape. It appears inanimate. YOUNG PROFESSOR (cont'd) Answer me. And finally, from within the ball, a faint alow. Slyly: BALL How can I? You unplugged me, Jor- El ... Remember? Recall? The Young Professor -- JOR-EL -- looks visibly shaken. y*fi^*\ (CONTINUED) CONTINUED: JOR-EL I did what I had to, I.A.C. -

Released 27Th May 2015 DARK HORSE COMICS MAR150030

Released 27th May 2015 DARK HORSE COMICS MAR150030 CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT #23 MAR150077 CONAN THE AVENGER #14 MAR150064 ELFQUEST FINAL QUEST #9 MAR150014 FIGHT CLUB 2 #1 MACK MAIN CVR MAR150084 FRANKENSTEIN UNDERGROUND #3 JAN150113 GRINDHOUSE DRIVE IN BLEED OUT #5(MR) MAR150061 HALO ESCALATION #18 MAR150027 MISTER X RAZED #4 MAR150028 ORDER OF THE FORGE #2 (MR) MAR150021 PASTAWAYS #3 JAN150142 SAVAGE SWORD OF CONAN TP VOL 19 MAR150062 TOMB RAIDER #16 JAN150173 TONY TAKEZAKIS NEON GENESIS EVANGELION TP DC COMICS FEB150250 BATGIRL TP VOL 05 DEADLINE (N52) MAR150255 BATMAN 66 #23 FEB150269 BATMAN ADVENTURES TP VOL 02 FEB150259 BATMAN LEGENDS OF THE DARK KNIGHT TP VOL 04 MAR150167 CONVERGENCE #8 (NOTE PRICE) MAR150231 CONVERGENCE ACTION COMICS #2 MAR150233 CONVERGENCE BLUE BEETLE #2 MAR150235 CONVERGENCE BOOSTER GOLD #2 MAR150237 CONVERGENCE CRIME SYNDICATE #2 MAR150239 CONVERGENCE DETECTIVE COMICS #2 MAR150241 CONVERGENCE INFINITY INC #2 MAR150243 CONVERGENCE JUSTICE SOCIETY OF AMERICA #2 MAR150245 CONVERGENCE PLASTIC MAN FREEDOM FIGHTERS #2 MAR150247 CONVERGENCE SHAZAM #2 MAR150249 CONVERGENCE WORLDS FINEST COMICS #2 MAR150301 EFFIGY #5 (MR) MAR150260 HE MAN THE ETERNITY WAR #6 MAR150253 INJUSTICE GODS AMONG US YEAR FOUR #2 DEC140262 MULTIVERSITY PAX AMERICANA DIRECTORS CUT #1 MAR150299 SANDMAN OVERTURE #5 COMBO PACK (MR) MAR150295 SANDMAN OVERTURE #5 CVR A (MR) MAR150296 SANDMAN OVERTURE #5 CVR B (MR) MAR150312 SUICIDERS #4 (MR) IDW PUBLISHING MAR150426 EDWARD SCISSORHANDS #8 WHOLE AGAIN MAR150428 EDWARD SCISSORHANDS TP VOL 01 PARTS UNKNOWN MAR150420 -

– EXTRA Level 3 This Level Is Suitable for Students Who Have Been Learning English for at Least Three Years and up to Four Years

S CHOLASTIC ELT READERS A FREE RESOURCE FOR TEACHERS! – EXTRA Level 3 This level is suitable for students who have been learning English for at least three years and up to four years. It corresponds with the Common European Framework level B1. Suitable for users of TEAM magazine. SYNOPSIS moment of her death by a supernatural cat called Midnight. She Patience Philips is young, single and very shy – she’s a designer is reborn still as Patience Philips, but now with an alter ego, a for Hedare Beauty, a top beauty products firm. One evening, super hero with the attributes of a cat – she is fast, dangerous while she is trying to rescue a strange cat from her window-sill, and very agile, and she can see in the dark. Patience is the latest she meets a handsome policeman called Tom Lone, and they in a long line of women who are chosen to be catwomen. are definitely interested in each other. There’s trouble at the The original Catwoman was a small-time criminal who turned office, though; her boss, George Hedare, doesn’t like her designs. good. This new Catwoman walks a thin line between being That night she overhears people talking about problems with good and bad. She steals jewellery, for instance, but then gives Hedare’s new miracle beauty product, Beau-line, which keeps it back … except, not all of it, because one piece is just too nice. skin young-looking. She hears too much and they kill her. The story focuses on cosmetics and how women are exploited The strange cat is actually a magical cat and brings her back by big beauty companies. -

With Great Power: Examining the Representation and Empowerment of Women in DC and Marvel Comics Kylee Kilbourne

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 12-2017 With Great Power: Examining the Representation and Empowerment of Women in DC and Marvel Comics Kylee Kilbourne Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kilbourne, Kylee, "With Great Power: Examining the Representation and Empowerment of Women in DC and Marvel Comics" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 433. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/433 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WITH GREAT POWER: EXAMINING THE REPRESENTATION AND EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN IN DC AND MARVEL COMICS by Kylee Kilbourne East Tennessee State University December 2017 An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment For the Midway Honors Scholars Program Department of Literature and Language College of Arts and Sciences ____________________________ Dr. Phyllis Thompson, Advisor ____________________________ Dr. Katherine Weiss, Reader ____________________________ Dr. Michael Cody, Reader 1 ABSTRACT Throughout history, comic books and the media they inspire have reflected modern society as it changes and grows. But women’s roles in comics have often been diminished as they become victims, damsels in distress, and sidekicks. This thesis explores the problems that female characters often face in comic books, but it also shows the positive representation that new creators have introduced over the years. -

Jack Is Dead

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-16-2008 Jack is Dead Connie Reeder University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Reeder, Connie, "Jack is Dead" (2008). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 669. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/669 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jack is Dead A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Fine Arts In Film, Theatre and Communication Arts Creative Writing by Connie “Conrad” Reeder B. A. Thomas A. Edison State College, 2005 May, 2008 © 2008, Connie “Conrad” Reeder ii Dedication To Cimcie and Ashlee for being alive. iii Acknowledgment I wish to thank the following people for their unwavering support: my husband, Roger Nichols; my daughters, Cimcie and Ashlee; my goddaughter, Daniella; my sisters, Lois, Betty, and Patty; the sisters of my heart, Melinda, Ana Gladys, and Pamela Wolfe—my fellow trickster; and much gratitude to Linda Wolverton for proof reading. -

Abbie Reilly – Song List

Joi Ride | Play List Pre 70s Rock Around the Clock Bill Hayley Shake Your Tailfeather Ray Charles 70s Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Boots/ Whole Lotta mash Dancing Queen ABBA Don’t Stop Fleetwood Mac Dreams Fleetwood Mac Everywhere Fleetwood Mac Fly Too High Janis Ian Funky Music Wild Cherry I Will Survive Gloria Gaynor Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley Mamma Mia ABBA Moondance Van Morrison Night Life Alicia Bridges Reminiscing Little River Band Rock n Roll Led Zeppelin Second Hand News Fleetwood Mac Shakey Ground The Temptations The One That I Want Grease These Boots Are Made for Walkin’ Nancy Sinatra Time Warp Rocky Horror Whole Lotta Love Led Zeppelin 80s Billie Jean Michael Jackson I Wish Stevie Wonder Kiss Prince Love Shack The B52s Smooth Operator Sade Superstition Stevie Wonder Sweet Dreams Eurythmics Teardrops Womack & Womack The Way U Make Me Feel Michael Jackson 90s Can’t Get You Outta My Head Kylie Minogue Groove is in the Heart D’Lite Hanky Panky Madonna Hit Me Baby One More Time Britney Spears Rush You Baby Animals Semi Charmed Life 3rd Eye Blind Sing It Back Moloko Sweet Child O’ Mine Guns n Roses Torn Natalie Imbruglia 2000s Crazy Gnarls Barkley Firework Katy Perry Forget you C D F C// Em Am Dm G Cee Lo Green Funhouse Pink Get Lucky Daft Punk Get the Party Started Pink Knock on Wood Eddie Floyd Price Tag Jesse J Roar Katy Perry So What Pink Treasure Bruno Mars Who Knew Pink Humorous |Themes I Wanna Do Bad Things With You True Blood theme song Roadhouse Blues The Doors Tribute (The Greatest Song in World) Tenacious D 4 Chord Song