THESIS Tom LANGIE 2014.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5129P Sell Sheets.Qxd 8/3/17 8:12 AM Page 1

At A Glance _5129P Sell sheets.qxd 8/3/17 8:12 AM Page 1 North America Nestlé Waters Nestlé Waters is part of the Nestlé NFeosrt léF oWuarte Drse Ncoartdhe As merica Inc.’s S.A. family of companies, headquartered At A Ghisltorya begann in 1976c with juest one 2i0n Vevey1, Switze7 rland. Founded by Henri brand, Perrier ® Sparkling Natural Nestlé in 1866, Nestlé S.A. celebrated its Mineral Water. Today we are the 150th anniversary and is the leading food third largest non-alcoholic beverage and beverage company in the world, company in the U.S. by volume and with more than 335,000 employees offer 11 bottled water brands and worldwide. Consumers know Nestlé best three ready-to-drink tea brands to for its respected brands, including ® ® our discerning and loyal consumers. Nescafé coffee, Gerber Foods, ® ® Our affiliate, Nestlé Waters Canada, Stouffer’s and Lean Cuisine frozen ® offers five bottled water brands to its foods and Purina pet products. Canadian consumers. Nestle aims to enhance people’s quality of life and contribute to a healthier future. Nestlé is the largest Our Commitments private funder of health and nutrition The Healthy Hydration Company TM Creating shared value for the business, the environment and communities is research globally. Its desire to provide brought to life every day by our of more consumers with “the very best” food than 8,500 employees and demonstrated throughout their lives is reflected in the by our positive work culture, high-quality famous Nestlé logo depicting a mother products, ever increasing responsibility bird feeding her young in the nest. -

Mexico Is the Number One Consumer of Coca-Cola in the World, with an Average of 225 Litres Per Person

Arca. Mexico is the number one Company. consumer of Coca-Cola in the On the whole, the CSD industry in world, with an average of 225 litres Mexico has recently become aware per person; a disproportionate of a consolidation process destined number which has surpassed the not to end, characterised by inventors. The consumption in the mergers and acquisitions amongst USA is “only” 200 litres per person. the main bottlers. The producers WATER & CSD This fizzy drink is considered an have widened their product Embotelladoras Arca essential part of the Mexican portfolio by also offering isotonic Coca-Cola Group people’s diet and can be found even drinks, mineral water, juice-based Monterrey, Mexico where there is no drinking water. drinks and products deriving from >> 4 shrinkwrappers Such trend on the Mexican market milk. Coca Cola Femsa, one of the SMI LSK 35 F is also evident in economical terms main subsidiaries of The Coca-Cola >> conveyor belts as it represents about 11% of Company in the world, operates in the global sales of The Coca Cola this context, as well as important 4 installation. local bottlers such as ARCA, CIMSA, BEPENSA and TIJUANA. The Coca-Cola Company These businesses, in addition to distributes 4 out of the the products from Atlanta, also 5 top beverage brands in produce their own label beverages. the world: Coca-Cola, Diet SMI has, to date, supplied the Coke, Sprite and Fanta. Coca Cola Group with about 300 During 2007, the company secondary packaging machines, a worked with over 400 brands and over 2,600 different third of which is installed in the beverages. -

Nestlé and Water Sustainability, Protection, Stewardship Nestlé and Water Sustainability, Protection, Stewardship

Good Food, Good Life Nestlé and Water Sustainability, Protection, Stewardship Nestlé and Water Sustainability, Protection, Stewardship Table of contents Case studies 3 Message from the CEO 17 From spas to a world market The history of bottled water around the world 5 Water, a scarce and renewable resource 23 France Sustainable development around sources 7 Nestlé, the world’s leading food 24 Argentina and beverage company Strengthening water resource protection 25 France 8 Nestlé’s commitment Preventing forest fires to sustainable water use 28 France 13 The Nestlé Water Policy Préférence, a partnership for sustainable milk production 14 Sustainable economic growth 31 Egypt Closed loop circuits to reduce water 18 Water and the environment and energy consumption 21 The water cycle 31 South Africa 22 Actively protecting water resources Saving water through employee involvement 27 Water in the Nestlé supply chain 32 Italy 44 The Nestlé Environmental Management System Optimising water use in factories 47 Environmental sponsorship 34 India Continuously improving waste water 50 Social aspects management 52 Relations with employees 34 Thailand 54 Meeting consumer needs Recycling suitable water streams 56 Involvement in the community 38 France Innovating the glassmaking process 61 Nestlé Research and Development 40 Vietnam Packaging renovation improves 63 The future environmental performance 40 Saudi Arabia A new life for plastic caps 46 Environmental management system Appointing “Environmental Guards” 48 From Italy to Tibet Cleaning up “the roof of the world” 49 Hungary Preserving Balaton National Park 53 Nestlé Waters Alacarte training to improve performance 57 USA, Mexico, Philippines and France Educating the water stewards of the future 58 South Africa Capacity building in water resource management 59 France, USA, Spain Water education through guided tours and exhibitions Nestlé and Water Sustainability, Protection, Stewardship 2 3 Message from the CEO Water is essential for life. -

Nestlé's Winning Formula for Brand Management

Feature By Véronique Musson Nestlé’s winning formula for brand management ‘Enormous’ hardly begins to describe the trademark that develop products worldwide and are managed from our portfolio of the world’s largest food and drink company headquarters in Vevey, Switzerland or St Louis in the United States,” he explains. So eight trademark advisers, also based in Vevey, advise one – and the workload involved in managing it. But when or more strategic business units on the protection of strategic it comes to finding the best solutions to protect these trademarks, designs and copyrights, while one adviser based in St very valuable assets, Nestlé has found that what works Louis advises the petcare strategic business unit on trademarks and best for it is looking for the answers in-house related issues, as the global petcare business has been managed from St Louis since the acquisition of Ralston Purina in 2001. In parallel, 16 regional IP advisers spread around the world advise the Nestlé Imagine that you start your day with a glass of VITTEL water operating companies (there were 487 production sites worldwide at followed by a cup of CARNATION Instant Breakfast drink. Mid- the end of 2005) on all aspects of intellectual property, including morning you have a cup of NESCAFÉ instant coffee and snack on a trademarks, with a particular focus on local marks. The trademark cheeky KIT KAT chocolate bar; lunch is a HERTA sausage with group also includes a dedicated lawyer in Vevey who manages the BUITONI pasta-and-sauce affair, finished off by a SKI yogurt. -

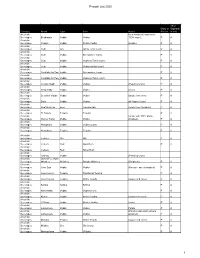

Pesach List 2020 1

Pesach List 2020 All or Dairy or Sephardi Category Brand Type Item Notes Pareve m only Alcoholic from Australia (made from Beverages Bushman's Vodka Vodka 100% cane). P A Alcoholic Beverages Chopin Vodka Potato Vodka (potato). P A Alcoholic Beverages Club Gin Gin & Tonic (corn). P A Alcoholic Beverages Club Vodka Screwdriver (corn). P A Alcoholic Beverages Club Vodka Vodka & Tonic (corn). P A Alcoholic Beverages Club Vodka Vodka Gimlet (corn). P A Alcoholic Beverages Cocktails for Two Vodka Screwdriver (corn). P A Alcoholic Beverages Cocktails for Two Vodka Vodka & Tonic (corn). P A Alcoholic Beverages Crystal Head Vodka Vodka (Peach & Corn) P A Alcoholic Beverages Deep Eddy Vodka Vodka (corn) P A Alcoholic Beverages Devotion Vodka Vodka Vodka (made from corn) P A Alcoholic Beverages Dixie Vodka Vodka all 4 types (corn) P A Alcoholic Beverages Dogfish Head Beer Tweason'ale (made from Sorghum) P A Alcoholic Beverages El Tosoro. Tequila Tequila P A Alcoholic (made with 100% Idaho Beverages Glacier Teton Vodka Vodka potatoes). P A Alcoholic Beverages Hampton's Vodka Vodka (Corn) P A Alcoholic Beverages Herradura. Tequila Tequila P A Alcoholic Beverages Iceberg Gin Gin P A Alcoholic Beverages Iceberg Rum Gold Rum P A Alcoholic Beverages Iceberg Rum Silver Rum Alcoholic Beverages Iceberg Vodka (Peach & Corn) Alcoholic James F.C. Hyde Beverages Whiskey Whiskey Sorgho Whiskey (Sorghum) P A Alcoholic Beverages Jinro Soju Vodka Vodka (Korean - sweet potatoes) P A Alcoholic Beverages Jose Cuervo Tequila Traditional Tequila P A Alcoholic Beverages Jose Cuervo Tequila White Tequila (agave and cane). P A Alcoholic Beverages Kahlua Kahlua Kahlua P A Alcoholic Beverages Kamchatka Vodka Vodka (corn). -

Trade Marks Opposition Decision (O/062/00)

TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF APPLICATION NO. 2105301 BY SAN CARLO GRUPPO ALIMENTARE SpA TO REGISTER THE MARK NESSIE IN CLASSES 29 AND 30 AND IN THE MATTER OF OPPOSITION THERETO UNDER NO. 46163 BY SOCIETE DES PRODUITS NESTLE SA TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF APPLICATION NO. 2105301 BY SAN CARLO GRUPPO ALIMENTARE SpA 5 TO REGISTER THE MARK NESSIE IN CLASSES 29 AND 30 AND 10 IN THE MATTER OF OPPOSITION THERETO UNDER NO. 46163 BY SOCIETE DES PRODUITS NESTLE SA 15 DECISION On 16 July 1996 San Carlo Gruppo Alimentare SpA applied to register the mark NESSIE for the following specifications of goods: 20 Class 29 Preserved, dried and cooked fruits and vegetables, potato products, edible oils and fats, preserves, pickles. Class 30 Farinaceous foods, snacks and foods comprising or containing flour, wheat flour and wheat meal; all included in Class 30. 25 The application is numbered 2105301. On 2 January 1997 Société des Produits Nestlé SA filed notice of opposition to this application. They say that they are the proprietors of numerous trade marks with the prefix 30 NES including, inter alia, NESTLE, NESCAFE and NESQUIK and that these marks have been used on an extensive basis. They also refer to various other registrations standing in their name. It is said that NESTLE, NESCAFE and NESQUIK are entitled to protection under the Paris Convention as well known trade marks. The specific grounds cited are: 35 (i) that the mark applied for does not meet the requirements of Section 1(1) of the Act and therefore falls within the prohibition of Section 3 (1)(a). -

2006 ANNUAL REPORT BUSINESS DESCRIPTION We Are the World’S Largest Marketer, Producer, and Distributor of Coca-Cola Products

2006 ANNUAL REPORT BUSINESS DESCRIPTION We are the world’s largest marketer, producer, and distributor of Coca-Cola products. In 2006, we distributed more than 2 billion physical cases of our products, or 42 billion bottles and cans, representing 19 percent of The Coca-Cola Company’s worldwide volume. We operate in 46 U.S. states and Canada; our territory encompasses approximately 81 percent of the North American population. In addition, we are the exclusive Coca-Cola bottler for all of Belgium, continental France, Great Britain, Luxembourg, Monaco, and the Netherlands. We employ 74,000 people, operate 444 facilities, 55,000 vehicles, and 2.4 million vending machines, beverage dispensers, and coolers. Our stock is traded on the New York Stock Exchange under the “CCE” symbol. TABLE OF CONTENTS Financial Highlights…fold-out Letter to Our Shareowners…1 A Case For Change…5 Financials…25 Shareowner Information…Inside Back Cover TERRITORIES OF OPERATION CANADA 3 Market Units 34 Sales Centers MIDWEST 6 Market Units 59 Sales Centers GREAT LAKES 6 Market Units 39 Sales Centers NORTHEAST 7 Market Units 46 Sales Centers WEST 9 Market Units 46 Sales Centers SOUTHEAST 8 Market Units 55 Sales Centers SOUTHWEST 6 Market Units 41 Sales Centers COCA-COLA ENTERPRISES AT-A-GLANCE GEOGRAPHIC CASE DISTRIBUTION BRAND MIX 42 billion bottles and cans, or 2 billion physical cases NORTH AMERICA 6% 8% 9% 24% 57% 26% 70% GREAT BRITAIN THE NETHERLANDS QUnited States QEurope QCanada QCoca-Cola Trademark QSoft Drink Flavors/Energy BELGIUM QSports Drinks/Juices/Teas QWater LUXEMBOURG EUROPE EUROPEAN CASE DISTRIBUTION BRAND MIX 9 billion bottles and cans, or 480 million physical cases EUROPE FRANCE 3% 10% 10% 18% 46% 19% 68% 26% QGreat Britain QFrance QCoca-Cola Trademark QSoft Drink Flavors/Energy QBelgiumlLuxembourg QThe Netherlands QSports Drinks/Juices/Teas QWater FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Coca-Cola Enterprises Inc. -

Caffeine Content in Foods and Beverages - Uptodate

16/02/2020 Caffeine content in foods and beverages - UpToDate Official reprint from UpToDate® © 2020 UpToDate, Inc. e/ou seus afiliados. Todos os direitos reservados.www.uptodate.com Caffeine content in foods and beverages Coffees Serving size, oz (mL) Caffeine, mg Coffee, brewed 8 (235) 133 (range: 102 to 200) Coffee, generic instant 8 (235) 93 (range: 27 to 173) Coffee, generic decaffeinated 8 (235) 5 (range: 3 to 12) Espresso 1 (30) 40 (range: 30 to 90) Espresso decaffeinated 1 (30) 4 Teas Serving size, oz (mL) Caffeine, mg Tea, brewed 8 (235) 53 (range: 40 to 120) Arizona Iced Tea, black 16 (470) 32 Arizona Iced Tea, green 16 (470) 15 Nestea 12 (355) 26 Snapple, Just Plain Unsweetened 16 (470) 18 Snapple, Kiwi Teawi 16 (470) 10 Snapple, Lemon, Peach, or Raspberry 16 (470) 42 Starbucks Tazo Chai Tea Latte (Grande) 16 (470) 100 Soft drinks Serving size, oz (mL) Caffeine, mg FDA official limit for cola and pepper soft 12 (355) 71 drinks 7-Up, regular or diet 12 (355) 0 Barq's Diet Root Beer 12 (355) 0 Barq's Root Beer 12 (355) 22 Coke, regular or diet 12 (355) 35 to 47 Dr. Pepper, regular or diet 12 (355) 42 to 44 Fanta, all flavors 12 (355) 0 Fresca, all flavors 12 (355) 0 Jolt Cola 12 (355) 72 Mellow Yellow 12 (355) 53 Mountain Dew, regular or diet 12 (355) 54 (20 oz = 90) Mountain Dew MDX, regular or diet 12 (355) 71 (20 oz = 118) Mug Root Beer, regular or diet 12 (355) 0 Pepsi, regular or diet 12 (355) 36 to 38 https://www.uptodate.com/contents/image/print?csi=dc8cf830-1b2b-4faa-9f01-bf4cf6c3967a&source=contentShare&imageKey=OBGYN%2F79304 -

Coffees Serving Size Caffeine (Mg)

Coffees Serving Size Caffeine (mg) Dunkin' Donuts Coffee with Turbo Shot large, 20 fl. oz. 436 Starbucks Coffee venti, 20 fl. oz. 415 Starbucks Coffee grande, 16 fl. oz. 330 Panera Frozen Mocha 16.5 fl. oz. 267 Starbucks Coffee tall, 12 fl. oz. 260 Starbucks Caffè Americano grande, 16 fl. oz. 225 Panera Coffee regular, 16.8 fl. oz. 189 Starbucks Espresso Frappuccino venti, 24 fl. oz. 185 Dunkin' Donuts Coffee medium, 14 fl. oz. 178 Starbucks Caffè Mocha grande, 16 fl. oz. 175 Starbucks Iced Coffee grande, 16 fl. oz. 165 Maxwell House Ground Coffee—100% Colombian, Dark Roast, 2 Tbs., makes 12 fl. Master Blend, or Original Roast oz. 100-160 Dunkin' Donuts Cappuccino large, 20 fl. oz. 151 Starbucks—Caffè Latte, Cappuccino, or Caramel Macchiato grande, 16 fl. oz. 150 Starbucks Espresso doppio, 2 fl. oz. 150 Keurig Coffee K-Cup, all varieties 1 cup, makes 8 fl. oz. 75-150 2 tsp., makes 12 fl. Folgers Classic Roast Instant Coffee oz. 148 Starbucks Doubleshot Energy Coffee, can 15 fl. oz. 146 Starbucks Mocha Frappuccino venti, 24 fl. oz. 140 1 packet, makes 8 fl. Starbucks VIA House Blend Instant Coffee oz. 135 McDonald's Coffee large, 16 fl. oz. 133 2⅔ Tbs., makes 12- Maxwell House International Café, all flavors 16 fl. oz. 40-130 Seattle's Best Coffee—Iced Latte or Iced Mocha, can 9.5 fl. oz. 90 Starbucks Frappuccino Coffee, bottle 9.5 fl. oz. 90 International Delight Iced Coffee 8 fl. oz. 76 2 Tbs., makes 12 fl. Maxwell House Lite Ground Coffee oz. -

Nestlé: Brand Alliances in Developing Markets

NESTLÉ: BRAND ALLIANCES IN DEVELOPING MARKETS Brian A. Vander Schee, Aurora University Timothy W. Aurand, Northern Illinois University Treneice Pickens, Northern Illinois University Mary Ma, Northern Illinois University Anand Ratnakar Girap, Northern Illinois University ABSTRACT Branding concepts often find a place in introductory marketing textbooks. However, given time and space considerations, covering those concepts with a comprehensive industry perspective is typically unachievable. Thus, supplementing textbook content with brief company cases can help students gain a better appreciation for the material with meaningful application. This paper presents a synopsis of brand alliance concepts appropriate for introductory marketing students. It then goes on to provide several examples of how the Nestlé Company uses these alliances as a competitive advantage particularly in developing markets. The conclusion includes questions for class discussion to stimulate further understanding and analysis of brand alliances in the marketplace. INTRODUCTION and Hartline 2010). A brand gives a product a unique identity that differentiates the product from other compet With increasing frequency, companies are undertak ing products in the marketplace. It lessens the risk of ing brand alliance partnerships. This is where two differ purchasing the product in the minds of customers and also ent companies pair their respective brands in a joint signifies quality. Customers remain loyal and committed marketing effort (Kapferer 2008). Co-branding in partic to a brand as long as the perceived value creates a sense of ular is often used as a strategy to establish a competitive satisfaction and benefit. For the company, a brand becomes advantage. It can strengthen the brand portfolio, leverage an asset that can be leveraged to gain a competitive established brand equity, provide a mechanism for the advantage in the marketplace (Armstrong and Kotler brand to enter future growth categories and reach impor 2011). -

Grocery Goliaths

HOW FOOD MONOPOLIES IMPACT CONSUMERS About Food & Water Watch Food & Water Watch works to ensure the food, water and fish we consume is safe, accessible and sustainable. So we can all enjoy and trust in what we eat and drink, we help people take charge of where their food comes from, keep clean, affordable, public tap water flowing freely to our homes, protect the environmental quality of oceans, force government to do its job protecting citizens, and educate about the importance of keeping shared resources under public control. Food & Water Watch California Office 1616 P St. NW, Ste. 300 1814 Franklin St., Ste. 1100 Washington, DC 20036 Oakland, CA 94612 tel: (202) 683-2500 tel: (510) 922-0720 fax: (202) 683-2501 fax: (510) 922-0723 [email protected] [email protected] foodandwaterwatch.org Copyright © December 2013 by Food & Water Watch. All rights reserved. This report can be viewed or downloaded at foodandwaterwatch.org. HOW FOOD MONOPOLIES IMPACT CONSUMERS Executive Summary . 2 Introduction . 3 Supersizing the Supermarket . 3 The Rise of Monolithic Food Manufacturers. 4 Intense consolidation throughout the supermarket . 7 Consumer choice limited. 7 Storewide domination by a few firms . 8 Supermarket Strategies to Manipulate Shoppers . 9 Sensory manipulation . .10 Product placement . .10 Slotting fees and category captains . .11 Advertising and promotions . .11 Conclusion and Recommendations. .12 Appendix A: Market Share of 100 Grocery Items . .13 Appendix B: Top Food Conglomerates’ Widespread Presence in the Grocery Store . .27 Methodology . .29 Endnotes. .30 Executive Summary Safeway.4 Walmart alone sold nearly a third (28.8 5 Groceries are big business, with Americans spending percent) of all groceries in 2012. -

Grocerylist Villaswildernesslod

DISNEY'S WILDERNESS LODGE VILLAS-GROCERY ORDER FORM A $5.00 service charge will be added to all orders ($10.00 effective June 1, 2011). Groceries will be delivered on date of check-in after 5:00 p.m. Check-In Date: Approx. Arrival Time: Please Circle One: Visa Mastercard American Express Discover Guest Name: Credit Card #: Exp. Date: Guest Daytime Phone #: Reservation #: Cardholder's Signature: Item Size Price QTY Item Size Price QTY Item Size Price QTY BAKED GOODS BEVERAGES cont. COFFEE/TEA Entenmann's Chocolate Covered Donuts 8 pk 4.59 Power-Aid Fruit Punch 20 oz. 2.89 Melitta Premium Roast Coffee Filter Pack single 1.45 Entenmann's Variety Softee Pack 12 pk 4.99 Power-Aid Mountain Blast 20 oz. 2.89 Maxwell House Instant Coffee Rich House 2 oz. 4.95 Entenmann's Powdered Mini Donuts 14 oz 3.49 Power-Aid Lemon Lime 20 oz. 2.89 Maxwell House Instant Coffee Regular 2 oz. 4.95 Entenmann's Donut Holes-Glazed 1 lb. 3.99 Fuze Peach Mango 18.5 oz 3.99 Lipton Tea Bags 16 qty. 1.95 Entenmann's Variety Pack Donuts 8 pk 4.59 Illy Cappuccino 8.45 oz 3.99 Disney Blend Coffee 12 oz. 9.95 Entenmann's Little Bites Blueberry Muffins 8.25 oz. 4.29 Full Throttle 16 oz. 3.99 Coffee Filters 50 ct. 1.95 Entenmann's Chocolate Chip Cookies 12 oz. 3.49 Tonic Water 1 liter 2.95 CONDIMENTS Size Price QTY Entenmann's Loaf Cake 2.75 oz 1.49 Ginger Ale 1 liter 2.95 Sugar 20 oz.