CHAPTER 5 Competitor Analysis and Intelligence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

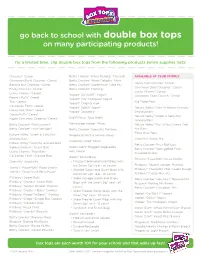

Go Back to School with Double Box Tops on Many Participating Products!

go back to school with double box tops on many participating products! for a limited time, clip double box tops from the following products (while supplies last): Cheerios® Cereal Betty Crocker® Warm Delights® Desserts AVAILABLE AT CLUB STORES: Cinnamon Burst Cheerios® Cereal Betty Crocker® Warm Delights® Minis Honey Nut Cheerios® Cereal Banana Nut Cheerios® Cereal Betty Crocker® SuperMoist® Cake Mix Cinnamon Burst Cheerios® Cereal Fruity Cheerios® Cereal Betty Crocker® Frosting Lucky Charms® Cereal Lucky Charms® Cereal Yoplait® Go-GURT® Yogurt Cinnamon Toast Crunch® Cereal Reese’s Pus® Cereal Yoplait® Trix® Multipack Yogurt Trix® Cereal Kid Triple Pack Yoplait® Original 4-pk Cascadian Farm® Cereal Yoplait® Splitz® Yogurt Nature Valley® Oats ‘N Honey Crunchy Honey Nut Chex® Cereal Yoplait® Smoothie Granola Bars Cocoa Pus® Cereal Nature Valley® Sweet & Salty Nut Apple Cinnamon Cheerios® Cereal Old El Paso® Taco Shells Granola Bars Betty Crocker® Fruit Gushers® Hamburger Helper® Mixes Nature Valley® Fruit & Nut Chewy Trail Betty Crocker® Fruit Roll-Ups® Betty Crocker® Specialty Potatoes Mix Bars Fiber One® Bars Nature Valley® Sweet & Salty Nut Progresso® Rich & Hearty Soups Granola Bars Chex Mix® Snack Mix Suddenly Salad® Mixes Nature Valley® Crunchy Granola Bars Betty Crocker® Fruit Roll-Ups® Golden Graham® Snack Bars Green Giant® Bagged Vegetables Betty Crocker® SpongeBob Fruit- Lucky Charms® Treat Bars with Sauce Flavored Snacks Cascadian Farm® Granola Bars Ziploc® brand Bags : Totino’s® Pizza Rolls® Pizza Snacks Chex Mix® Snack Mix -

Pop-Up Grocery Stores Hospital Implementation Guide Concept Overview

Pop-Up Grocery Stores Hospital Implementation Guide Concept Overview Context: • Many hospitals are limiting or closing their communal cafeteria offerings as protocol to face coronavirus • Doctors, nurses and other hospital staff may find their supermarkets are out of basic necessities when they are able to shop for their families after their hospital shifts • Hospitals still have access to a wide range of items from their foodservice distributors Solution: • Hospitals can convert their unused cafeteria space into temporary, pop-up grocery stores for staff • Stock the shelves with the products you already buy and make simple adjustments to tailor the offering to a grocery setting • See our General Mills category management recommendation in the following slides to bring this concept to life in your hospital, using the products you have on hand to serve the caregivers throughout your hospital Category Management Best Practices • Prioritize “Everyday Essentials” • Milk, Eggs, Cheese, Produce, Paper Products, Meat, Cereal, Bread/Baked Goods Category Reach (Based on Household Penetration & Purchase Frequency) • Consider “Family Entertainment” Options: Targeted Essentials Occasional Essentials Everyday Essentials Diapers Butter/Margarine Milk RTE Cereal • Microwave popcorn, baking mixes, frosting/icing Wine/Beer Coffee Eggs Bread Baby Food Flour Cheese Sugar/Sweeteners Paper Products Laundry Supplies Fresh Produce HH Cleaners Fresh Meat • As shelf/cooler space allows, bring in additional individually saleable foodservice Targeted Staples Occasional -

Here's Ration Relief! Finely, and Use for Rolling Chops Or

finely, and use for rolling chops or croquettes. W’heaties make a deli- cious crusty topping, too, for many different casserole dishes. Here’s Ration Relief! ? ? ? By BETTY CROCKER EARLY A. M. BACKER-UPPER! Lady of jn I tfflT.' First Food When your folks roll out, morn- T are having to cut down on cerenl* finnl value* tee nee cl (another B Vitamin), and iron. ings, they’ve been fasting for yOIcert ain foods you’ve boon serv- et'ery tingle tiny, in the diet. Good protein*, 100. Infact,the pro- around twelve hours or more. ing? There’ll a bright side to the ? * ? teins in a bowl of Wheatie* and milk Good Idea to break that fast with picture, however. Not all foods are # CONSIDER MEAT’S FOOD are as valuable as an etjual amount a nourishing whole wheat break- scarce. And you’re clever. You can VALUE. Some of moat’s nutrients of meat proteins! A bowl of Wheaties fast. Big cheery bowls of Wheat- figure out good substitutions. are provided by W heaties those with milkor cream isfinefor lunch or ies, with milkand fruit. Try this ? ? ? crisp toasted whole wheat flakes. supper, occasionally. It's satisfying, tomorrow: # CEREALS FOR INSTANCE. (A “whole grain” cereal that quali- ir * ? ('.hilled Orange Juice (ZerealHare plentiful. Ihey 'jenoi fies under Government's Nutrition #MEAT-EXTENDER,TOO. Add Wheaties with Milk or Cream rot inneil. Ami there* « valuable Food Rules.) Wheaties provide Wheaties to hamburger, or ground Toasted Cinnamon Rolls mntrish men t in whole grain Thiamine (Vitamin 13,), Niacin round steak. -

General Mills General Mills

Annual Report 2008 General Mills Continuing Growth Welcome to General Mills Net Sales by U.S. Retail Division U.S. Retail $9.1 billion in total Our U.S. Retail business segment includes the major marketing divisions 22% Big G Cereals listed to the left. We market our products in a variety of domestic retail 22% Meals outlets including traditional grocery stores, natural food chains, mass 19% Pillsbury USA merchandisers and membership stores. This segment accounts for 14% Yoplait 66 percent of total company sales. 13% Snacks 8% Baking Products 2% Small Planet Foods/Other Net Sales by International Region international $2.6 billion in total We market our products in more than 100 countries outside of the 35% Europe United States. Our largest international brands are Häagen-Dazs ice 27% Canada cream, Old El Paso Mexican foods and Nature Valley granola bars. This 23% Asia/Pacifi c business segment accounts for 19 percent of total company sales. 15% Latin America and South Africa Net Sales by Foodservice Bakeries And Foodservice Customer Segment We customize packaging of our retail products and market them to $2.0 billion in total convenience stores and foodservice outlets such as schools, restaurants 46% Bakery Channels and hotels. We sell baking mixes and frozen dough-based products to 45% Distributors/Restaurants supermarket, retail and wholesale bakeries. We also sell branded food 9% Convenience Stores/Vending products to foodservice operators, wholesale distributors and bakeries. This segment accounts for 15 percent of total company sales. Net Sales by Joint Venture Ongoing Joint Ventures (not consolidated) We are partners in several joint ventures. -

The Brands They Love for Cacfp

the brands they love for cacfp More than 70 eligible products for the Child and Adult Care Food Program all with no artificial flavors, no colors from artificial sources, and no high fructose corn syrup! UPC PRODUCT DESCRIPTION UPC PRODUCT DESCRIPTION ON-THE-GO POUCH CEREAL GOLD MEDALTM MIX 100-16000-31529-4 Whole Grain Variety Mun Mix 100-16000-14401-6 25% Less Sugar Cinnamon Toast Crunch™ Cereal On-The-Go Pouch NEW! 100-16000-31527-0 Whole Grain Complete Pancake Mix BOWLPAK CEREAL YOPLAIT PORTABLE YOGURT 100-16000-32262-9 Cheerios™ 100-70470-49295-4 Simply Go-Gurt Strawberry 2 oz 100-16000-38387-3 Cinnamon Chex™ 100-70470-14914-8 Go Big™ Blueberry 4 oz NEW! 100-16000-29444-5 25% Less Sugar Cinnamon Toast Crunch™ 100-70470-47402-8 Go Big™ Strawberry 4 oz 100-16000-33213-0 Corn Chex™ YOPLAIT YOGURT 4OZ 100-16000-11942-7 Kix™ 000-70470-17725-0 Trix™ Raspberry Rainbow 100-16000-32263-6 Multi Grain Cheerios™ 000-70470-17726-7 Trix™ Strawberry Banana Bash 100-16000-31921-6 Rice Chex™ 100-70470-31077-7 Trix™ Triple Cherry CUP CEREAL 000-70470-17729-8 Yoplait Original Strawberry/Strawberry Banana 25% Less Sugar Cinnamon Toast Crunch™ 000-70470-17728-1 Yoplait Original Red Raspberry/Harvest Peach 100-16000-14886-1 2oz Eq. Grain Cereal NEW! YOPLAIT ORIGINAL YOGURT 6OZ 100-16000-14883-0 Cinnamon Chex™ 2oz Eq. Grain Cereal NEW! 100-70470-00302-0 Original Mountain Blueberry BULK CEREAL 100-70470-00303-7 Original Cherry Orchard 100-16000-11977-9 Cheerios™ 100-70470-00323-5 Original French Vanilla 100-16000-13326-3 Corn Chex™ 100-70470-00306-8 Original -

5129P Sell Sheets.Qxd 8/3/17 8:12 AM Page 1

At A Glance _5129P Sell sheets.qxd 8/3/17 8:12 AM Page 1 North America Nestlé Waters Nestlé Waters is part of the Nestlé NFeosrt léF oWuarte Drse Ncoartdhe As merica Inc.’s S.A. family of companies, headquartered At A Ghisltorya begann in 1976c with juest one 2i0n Vevey1, Switze7 rland. Founded by Henri brand, Perrier ® Sparkling Natural Nestlé in 1866, Nestlé S.A. celebrated its Mineral Water. Today we are the 150th anniversary and is the leading food third largest non-alcoholic beverage and beverage company in the world, company in the U.S. by volume and with more than 335,000 employees offer 11 bottled water brands and worldwide. Consumers know Nestlé best three ready-to-drink tea brands to for its respected brands, including ® ® our discerning and loyal consumers. Nescafé coffee, Gerber Foods, ® ® Our affiliate, Nestlé Waters Canada, Stouffer’s and Lean Cuisine frozen ® offers five bottled water brands to its foods and Purina pet products. Canadian consumers. Nestle aims to enhance people’s quality of life and contribute to a healthier future. Nestlé is the largest Our Commitments private funder of health and nutrition The Healthy Hydration Company TM Creating shared value for the business, the environment and communities is research globally. Its desire to provide brought to life every day by our of more consumers with “the very best” food than 8,500 employees and demonstrated throughout their lives is reflected in the by our positive work culture, high-quality famous Nestlé logo depicting a mother products, ever increasing responsibility bird feeding her young in the nest. -

Determining Supply Chain Variability at General Mills

Determining Supply Chain Variability at General Mills L to R: Frederick Zhou, Christine England, Teresa Viola, Rajat Bhatia, and Carol German With roots going back to 1856, founded in 1928 and headquartered in Golden Valley, Minnesota, a Minneapolis suburb, General Mills, Inc. is a multinational manufacturer and marketer of branded consumer foods and other packaged goods sold through retail stores in more than 100 countries. The company, which reported 2017 revenue of $15.6 billion, operates approximately 79 food production facilities in a more than The General Mills Tauber team was tasked with a dozen countries, and has approximately 38,000 employees. It determining cumulative effects of common variability manufactures cereals, snacks, yogurt, and other food products under sources on the supply chain performance. such well-known brands as Gold Medal fl our, Annie’s Homegrown, Betty Crocker, Yoplait, Colombo, Totino’s, Pillsbury, Old El Paso, Häagen-Dazs, Nature Valley, Cheerios, Trix, Cocoa Puffs, Wheaties, and Lucky Charms. “These interviews allowed the team members to understand General Mills’ operations with more depth,” said Viola. General Mills supplies major retailers and provides services to its core customers for improving display confi gurations and stocking The Tauber team also created a variability network illustrating cause solutions. The company prides itself on best-in-class customer and effect relationships in the supply chain, and identifi ed key service and continually seeks to improve its service performance. variability sources that affect customer service performance. But over the past three years, variability has increasingly affected “The original project endeavored to establish and quantify linear or customer service performance and cost, while the cumulative nonlinear relationships between variability sources, and intermediate nature of these effects is only partially understood by supply chain and fi nal metrics,” said Viola. -

Participating Products ™

powered by For My School PARTICIPATING PRODUCTS ™ ANNIE’S® Minions Cereal Vanilla Vibe REFRIGERATED & DAIRY Nature Valley™ Oatmeal Baking Mix Nature Valley™ Baked Oat LAND O’LAKES® Butter Squares Cereal Bites Oui® by Yoplait® (4-6oz) Nature Valley™ Biscuits Cheesy Rice Nature Valley™ Granola Pillsbury™ Crescents Nature Valley™ Granola Cups Cookies Crunch Pillsbury™ Grands Protein One™ Bars Crackers Nature Valley™ Oat Clusters Pillsbury™ Cookies Nature Valley™ Snack Mix Fruit Snacks Nature Valley™ Protein Pillsbury™ Pizza and Nature Valley™ Wafers Granola Bars Crunchy Granola Pie Crust Nature Valley™ Packed Bars Graham Snacks Nature Valley™ Protein Yoplait® Go-GURT® and Pillsbury™ Soft Baked Bars Soft Baked ® Mac & Cheese Simply Go-GURT Yogurt Nature Valley™ Toasted ® Pasta Quinoa Rice Yoplait Go-gurt Dunkers WHOLESOME PANTRY Oats Muesli ® Pizza Bagels Yoplait Light & Original Wholesome Pantry Organic Oatmeal Crisp™ Pizza Poppers Fridge Packs (8ct) Peanut Butter Peanut Butter Chocolate ® Popcorn Yoplait Kids Yogurt Wholesome Pantry Organic Blasted Shreds™ Multipack Refrigerated Baked Goods Frozen Fruit Raisin Nut Bran Yoplait® Trix™ Yogurt Wholesome Pantry Organic Rice Pasta Chowder ® Reese’s Puffs Multipack Maple Syrup Rice Shell Pasta Rice Chex™ Yoplait® (4-6oz) Wholesome Pantry Almond Snack Mix Strawberry Toast Crunch™ Yoplait® Smoothie Milk Soup Total™ YQ® by Yoplait® Yogurt Trix™ Wheaties™ SHOPRITE BRAND BAKING ShopRite Frozen Appetizers Betty Crocker™ Baking Mixes FROZEN ShopRite Flexible Straws Betty Crocker™ Frosting Green Giant™ -

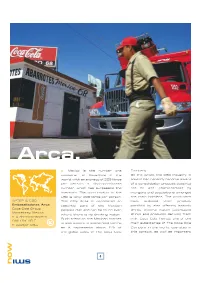

Mexico Is the Number One Consumer of Coca-Cola in the World, with an Average of 225 Litres Per Person

Arca. Mexico is the number one Company. consumer of Coca-Cola in the On the whole, the CSD industry in world, with an average of 225 litres Mexico has recently become aware per person; a disproportionate of a consolidation process destined number which has surpassed the not to end, characterised by inventors. The consumption in the mergers and acquisitions amongst USA is “only” 200 litres per person. the main bottlers. The producers WATER & CSD This fizzy drink is considered an have widened their product Embotelladoras Arca essential part of the Mexican portfolio by also offering isotonic Coca-Cola Group people’s diet and can be found even drinks, mineral water, juice-based Monterrey, Mexico where there is no drinking water. drinks and products deriving from >> 4 shrinkwrappers Such trend on the Mexican market milk. Coca Cola Femsa, one of the SMI LSK 35 F is also evident in economical terms main subsidiaries of The Coca-Cola >> conveyor belts as it represents about 11% of Company in the world, operates in the global sales of The Coca Cola this context, as well as important 4 installation. local bottlers such as ARCA, CIMSA, BEPENSA and TIJUANA. The Coca-Cola Company These businesses, in addition to distributes 4 out of the the products from Atlanta, also 5 top beverage brands in produce their own label beverages. the world: Coca-Cola, Diet SMI has, to date, supplied the Coke, Sprite and Fanta. Coca Cola Group with about 300 During 2007, the company secondary packaging machines, a worked with over 400 brands and over 2,600 different third of which is installed in the beverages. -

Nestlé and Water Sustainability, Protection, Stewardship Nestlé and Water Sustainability, Protection, Stewardship

Good Food, Good Life Nestlé and Water Sustainability, Protection, Stewardship Nestlé and Water Sustainability, Protection, Stewardship Table of contents Case studies 3 Message from the CEO 17 From spas to a world market The history of bottled water around the world 5 Water, a scarce and renewable resource 23 France Sustainable development around sources 7 Nestlé, the world’s leading food 24 Argentina and beverage company Strengthening water resource protection 25 France 8 Nestlé’s commitment Preventing forest fires to sustainable water use 28 France 13 The Nestlé Water Policy Préférence, a partnership for sustainable milk production 14 Sustainable economic growth 31 Egypt Closed loop circuits to reduce water 18 Water and the environment and energy consumption 21 The water cycle 31 South Africa 22 Actively protecting water resources Saving water through employee involvement 27 Water in the Nestlé supply chain 32 Italy 44 The Nestlé Environmental Management System Optimising water use in factories 47 Environmental sponsorship 34 India Continuously improving waste water 50 Social aspects management 52 Relations with employees 34 Thailand 54 Meeting consumer needs Recycling suitable water streams 56 Involvement in the community 38 France Innovating the glassmaking process 61 Nestlé Research and Development 40 Vietnam Packaging renovation improves 63 The future environmental performance 40 Saudi Arabia A new life for plastic caps 46 Environmental management system Appointing “Environmental Guards” 48 From Italy to Tibet Cleaning up “the roof of the world” 49 Hungary Preserving Balaton National Park 53 Nestlé Waters Alacarte training to improve performance 57 USA, Mexico, Philippines and France Educating the water stewards of the future 58 South Africa Capacity building in water resource management 59 France, USA, Spain Water education through guided tours and exhibitions Nestlé and Water Sustainability, Protection, Stewardship 2 3 Message from the CEO Water is essential for life. -

Nestlé's Winning Formula for Brand Management

Feature By Véronique Musson Nestlé’s winning formula for brand management ‘Enormous’ hardly begins to describe the trademark that develop products worldwide and are managed from our portfolio of the world’s largest food and drink company headquarters in Vevey, Switzerland or St Louis in the United States,” he explains. So eight trademark advisers, also based in Vevey, advise one – and the workload involved in managing it. But when or more strategic business units on the protection of strategic it comes to finding the best solutions to protect these trademarks, designs and copyrights, while one adviser based in St very valuable assets, Nestlé has found that what works Louis advises the petcare strategic business unit on trademarks and best for it is looking for the answers in-house related issues, as the global petcare business has been managed from St Louis since the acquisition of Ralston Purina in 2001. In parallel, 16 regional IP advisers spread around the world advise the Nestlé Imagine that you start your day with a glass of VITTEL water operating companies (there were 487 production sites worldwide at followed by a cup of CARNATION Instant Breakfast drink. Mid- the end of 2005) on all aspects of intellectual property, including morning you have a cup of NESCAFÉ instant coffee and snack on a trademarks, with a particular focus on local marks. The trademark cheeky KIT KAT chocolate bar; lunch is a HERTA sausage with group also includes a dedicated lawyer in Vevey who manages the BUITONI pasta-and-sauce affair, finished off by a SKI yogurt. -

Fiscal 2018 Annual Report

FISCAL 2018 ANNUAL REPORT Fiscal 2018 Financial Highlights Change In millions, except per share and 52 weeks ended 52 weeks ended on a constant- profit margin data May 27, 2018 May 28, 2017 Change currency basis* Net Sales $ 15,740 $ 15,620 1% Organic Net Sales* Flat Operating Profit $ 2,509 $ 2,566 (2%) Total Segment Operating Profit* $ 2,792 $ 2,953 (5%) (6%) Operating Profit Margin 15.9% 16.4% -50 basis points Adjusted Operating Profit Margin* 17.2% 18.1% -90 basis points Net Earnings Attributable to General Mills $ 2,131 $ 1,658 29% Diluted Earnings per Share (EPS) $ 3.64 $ 2.77 31% Adjusted Diluted EPS, Excluding Certain $ 3.11 $ 3.08 1% Flat Items Affecting Comparability* Average Diluted Shares Outstanding 586 598 (2%) Dividends per Share $ 1.96 $ 1.92 2% Net Sales Total Segment Adjusted Diluted Free Cash Flow* Dollars in millions Operating Profit* Earnings per Share* Dollars in millions Dollars in millions Dollars $3.11 $3,154 $17,910 $2,218 $17,630 $3,035 $3,000 $3.08 $2,953 $16,563 $2,035 $2,792 $1,959 $15,740 $15,620 $1,936 $1,731 $2.92 $2.86 $2.82 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 *See page 45 of form 10-K herein for discussion of non-GAAP measures. Fiscal 2018 Net Sales $15.7 Billion Total Company Net Sales by Product Platform Total Company Net Sales by Reporting Segment Our portfolio is focused on five global growth In fiscal 2018, we reported net sales in four platforms.