Handout 21: Distributed Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edsger Dijkstra: the Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders

INFERENCE / Vol. 5, No. 3 Edsger Dijkstra The Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders Krzysztof Apt s it turned out, the train I had taken from dsger dijkstra was born in Rotterdam in 1930. Nijmegen to Eindhoven arrived late. To make He described his father, at one time the president matters worse, I was then unable to find the right of the Dutch Chemical Society, as “an excellent Aoffice in the university building. When I eventually arrived Echemist,” and his mother as “a brilliant mathematician for my appointment, I was more than half an hour behind who had no job.”1 In 1948, Dijkstra achieved remarkable schedule. The professor completely ignored my profuse results when he completed secondary school at the famous apologies and proceeded to take a full hour for the meet- Erasmiaans Gymnasium in Rotterdam. His school diploma ing. It was the first time I met Edsger Wybe Dijkstra. shows that he earned the highest possible grade in no less At the time of our meeting in 1975, Dijkstra was 45 than six out of thirteen subjects. He then enrolled at the years old. The most prestigious award in computer sci- University of Leiden to study physics. ence, the ACM Turing Award, had been conferred on In September 1951, Dijkstra’s father suggested he attend him three years earlier. Almost twenty years his junior, I a three-week course on programming in Cambridge. It knew very little about the field—I had only learned what turned out to be an idea with far-reaching consequences. a flowchart was a couple of weeks earlier. -

Reinventing Education Based on Data and What Works • Since 1955

Reinventing Education Based on Data and What Works • Since 1955 Carnegie Mellon is reinventing education and the way we think about leveraging technology through its study of the science of learning – an interdisciplinary effort that we’ve been tackling for more than 50 years with both computer scientists and psychologists. CMU's educational technology innovations have inspired numerous startup companies, which are helping students to learn more effectively and efficiently. 1955: Allen Newell (TPR ’57) joins 1995: Prof. Kenneth R. Koedinger (HSS Prof. Herbert Simon’s research team as ’88,’90) and Anderson develop Practical a Ph.D. student. Algebra Tutor. The program pioneers a new form of computer-aided instruction for high 1956: CMU creates one of the world’s first school students based on cognitive tutors. university computation centers. With Prof. Alan Perlis (MCS ’42) as its head, it is a joint 1995: Prof. Jack Mostow (SCS ’81) undertaking of faculty from the business, develops Project LISTEN, an intelligent tutor Simon, Newell psychology, electrical engineering and that helps children learn to read. The National mathematics departments, and the Science Foundation included Project precursor to computer science. LISTEN’s speech recognition system as one of its top 50 innovations from 1950-2000. 1956: Simon creates a “thinking machine”—enacting a mental process 1995: The Center for Automated by breaking it down into its simplest Learning and Discovery is formed, led steps. Later that year, the term “artificial by Prof. Thomas M. Mitchell. intelligence” is coined by a small group Perlis including Newell and Simon. 1998: Spinoff company Carnegie Learning is founded by CMU scientists to expand 1956: Simon, Newell and J. -

On-The-Fly Garbage Collection: an Exercise in Cooperation

8. HoIn, B.K.P. Determining lightness from an image. Comptr. Graphics and Image Processing 3, 4(Dec. 1974), 277-299. 9. Huffman, D.A. Impossible objects as nonsense sentences. In Machine Intelligence 6, B. Meltzer and D. Michie, Eds., Edinburgh U. Press, Edinburgh, 1971, pp. 295-323. 10. Mackworth, A.K. Consistency in networks of relations. Artif. Intell. 8, 1(1977), 99-118. I1. Marr, D. Simple memory: A theory for archicortex. Philos. Trans. Operating R.S. Gaines Roy. Soc. B. 252 (1971), 23-81. Systems Editor 12. Marr, D., and Poggio, T. Cooperative computation of stereo disparity. A.I. Memo 364, A.I. Lab., M.I.T., Cambridge, Mass., 1976. On-the-Fly Garbage 13. Minsky, M., and Papert, S. Perceptrons. M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1968. Collection: An Exercise in 14. Montanari, U. Networks of constraints: Fundamental properties and applications to picture processing. Inform. Sci. 7, 2(April 1974), Cooperation 95-132. 15. Rosenfeld, A., Hummel, R., and Zucker, S.W. Scene labelling by relaxation operations. IEEE Trans. Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Edsger W. Dijkstra SMC-6, 6(June 1976), 420-433. Burroughs Corporation 16. Sussman, G.J., and McDermott, D.V. From PLANNER to CONNIVER--a genetic approach. Proc. AFIPS 1972 FJCC, Vol. 41, AFIPS Press, Montvale, N.J., pp. 1171-1179. Leslie Lamport 17. Sussman, G.J., and Stallman, R.M. Forward reasoning and SRI International dependency-directed backtracking in a system for computer-aided circuit analysis. A.I. Memo 380, A.I. Lab., M.I.T., Cambridge, Mass., 1976. A.J. Martin, C.S. -

The Advent of Recursion & Logic in Computer Science

The Advent of Recursion & Logic in Computer Science MSc Thesis (Afstudeerscriptie) written by Karel Van Oudheusden –alias Edgar G. Daylight (born October 21st, 1977 in Antwerpen, Belgium) under the supervision of Dr Gerard Alberts, and submitted to the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MSc in Logic at the Universiteit van Amsterdam. Date of the public defense: Members of the Thesis Committee: November 17, 2009 Dr Gerard Alberts Prof Dr Krzysztof Apt Prof Dr Dick de Jongh Prof Dr Benedikt Löwe Dr Elizabeth de Mol Dr Leen Torenvliet 1 “We are reaching the stage of development where each new gener- ation of participants is unaware both of their overall technological ancestry and the history of the development of their speciality, and have no past to build upon.” J.A.N. Lee in 1996 [73, p.54] “To many of our colleagues, history is only the study of an irrele- vant past, with no redeeming modern value –a subject without useful scholarship.” J.A.N. Lee [73, p.55] “[E]ven when we can't know the answers, it is important to see the questions. They too form part of our understanding. If you cannot answer them now, you can alert future historians to them.” M.S. Mahoney [76, p.832] “Only do what only you can do.” E.W. Dijkstra [103, p.9] 2 Abstract The history of computer science can be viewed from a number of disciplinary perspectives, ranging from electrical engineering to linguistics. As stressed by the historian Michael Mahoney, different `communities of computing' had their own views towards what could be accomplished with a programmable comput- ing machine. -

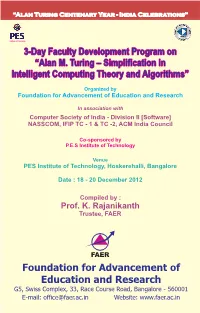

Alan M. Turing – Simplification in Intelligent Computing Theory and Algorithms”

“Alan Turing Centenary Year - India Celebrations” 3-Day Faculty Development Program on “Alan M. Turing – Simplification in Intelligent Computing Theory and Algorithms” Organized by Foundation for Advancement of Education and Research In association with Computer Society of India - Division II [Software] NASSCOM, IFIP TC - 1 & TC -2, ACM India Council Co-sponsored by P.E.S Institute of Technology Venue PES Institute of Technology, Hoskerehalli, Bangalore Date : 18 - 20 December 2012 Compiled by : Prof. K. Rajanikanth Trustee, FAER “Alan Turing Centenary Year - India Celebrations” 3-Day Faculty Development Program on “Alan M. Turing – Simplification in Intelligent Computing Theory and Algorithms” Organized by Foundation for Advancement of Education and Research In association with Computer Society of India - Division II [Software], NASSCOM, IFIP TC - 1 & TC -2, ACM India Council Co-sponsored by P.E.S Institute of Technology December 18 – 20, 2012 Compiled by : Prof. K. Rajanikanth Trustee, FAER Foundation for Advancement of Education and Research G5, Swiss Complex, 33, Race Course Road, Bangalore - 560001 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.faer.ac.in PREFACE Alan Mathison Turing was born on June 23rd 1912 in Paddington, London. Alan Turing was a brilliant original thinker. He made original and lasting contributions to several fields, from theoretical computer science to artificial intelligence, cryptography, biology, philosophy etc. He is generally considered as the father of theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence. His brilliant career came to a tragic and untimely end in June 1954. In 1945 Turing was awarded the O.B.E. for his vital contribution to the war effort. In 1951 Turing was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. -

![Arxiv:1909.05204V3 [Cs.DC] 6 Feb 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9182/arxiv-1909-05204v3-cs-dc-6-feb-2020-359182.webp)

Arxiv:1909.05204V3 [Cs.DC] 6 Feb 2020

Cogsworth: Byzantine View Synchronization Oded Naor, Technion and Calibra Mathieu Baudet, Calibra Dahlia Malkhi, Calibra Alexander Spiegelman, VMware Research Most methods for Byzantine fault tolerance (BFT) in the partial synchrony setting divide the local state of the nodes into views, and the transition from one view to the next dictates a leader change. In order to provide liveness, all honest nodes need to stay in the same view for a sufficiently long time. This requires view synchronization, a requisite of BFT that we extract and formally define here. Existing approaches for Byzantine view synchronization incur quadratic communication (in n, the number of parties). A cascade of O(n) view changes may thus result in O(n3) communication complexity. This paper presents a new Byzantine view synchronization algorithm named Cogsworth, that has optimistically linear communication complexity and constant latency. Faced with benign failures, Cogsworth has expected linear communication and constant latency. The result here serves as an important step towards reaching solutions that have overall quadratic communication, the known lower bound on Byzantine fault tolerant consensus. Cogsworth is particularly useful for a family of BFT protocols that already exhibit linear communication under various circumstances, but suffer quadratic overhead due to view synchro- nization. 1. INTRODUCTION Logical synchronization is a requisite for progress to be made in asynchronous state machine repli- cation (SMR). Previous Byzantine fault tolerant (BFT) synchronization mechanisms incur quadratic message complexities, frequently dominating over the linear cost of the consensus cores of BFT so- lutions. In this work, we define the view synchronization problem and provide the first solution in the Byzantine setting, whose latency is bounded and communication cost is linear, under a broad set of scenarios. -

Mathematical Writing by Donald E. Knuth, Tracy Larrabee, and Paul M

Mathematical Writing by Donald E. Knuth, Tracy Larrabee, and Paul M. Roberts This report is based on a course of the same name given at Stanford University during autumn quarter, 1987. Here's the catalog description: CS 209. Mathematical Writing|Issues of technical writing and the ef- fective presentation of mathematics and computer science. Preparation of theses, papers, books, and \literate" computer programs. A term paper on a topic of your choice; this paper may be used for credit in another course. The first three lectures were a \minicourse" that summarized the basics. About two hundred people attended those three sessions, which were devoted primarily to a discussion of the points in x1 of this report. An exercise (x2) and a suggested solution (x3) were also part of the minicourse. The remaining 28 lectures covered these and other issues in depth. We saw many examples of \before" and \after" from manuscripts in progress. We learned how to avoid excessive subscripts and superscripts. We discussed the documentation of algorithms, com- puter programs, and user manuals. We considered the process of refereeing and editing. We studied how to make effective diagrams and tables, and how to find appropriate quota- tions to spice up a text. Some of the material duplicated some of what would be discussed in writing classes offered by the English department, but the vast majority of the lectures were devoted to issues that are specific to mathematics and/or computer science. Guest lectures by Herb Wilf (University of Pennsylvania), Jeff Ullman (Stanford), Leslie Lamport (Digital Equipment Corporation), Nils Nilsson (Stanford), Mary-Claire van Leunen (Digital Equipment Corporation), Rosalie Stemer (San Francisco Chronicle), and Paul Halmos (University of Santa Clara), were a special highlight as each of these outstanding authors presented their own perspectives on the problems of mathematical communication. -

Verification and Specification of Concurrent Programs

Verification and Specification of Concurrent Programs Leslie Lamport 16 November 1993 To appear in the proceedings of a REX Workshop held in The Netherlands in June, 1993. Verification and Specification of Concurrent Programs Leslie Lamport Digital Equipment Corporation Systems Research Center Abstract. I explore the history of, and lessons learned from, eighteen years of assertional methods for specifying and verifying concurrent pro- grams. I then propose a Utopian future in which mathematics prevails. Keywords. Assertional methods, fairness, formal methods, mathemat- ics, Owicki-Gries method, temporal logic, TLA. Table of Contents 1 A Brief and Rather Biased History of State-Based Methods for Verifying Concurrent Systems .................. 2 1.1 From Floyd to Owicki and Gries, and Beyond ........... 2 1.2Temporal Logic ............................ 4 1.3 Unity ................................. 5 2 An Even Briefer and More Biased History of State-Based Specification Methods for Concurrent Systems ......... 6 2.1 Axiomatic Specifications ....................... 6 2.2 Operational Specifications ...................... 7 2.3 Finite-State Methods ........................ 8 3 What We Have Learned ........................ 8 3.1 Not Sequential vs. Concurrent, but Functional vs. Reactive ... 8 3.2Invariance Under Stuttering ..................... 8 3.3 The Definitions of Safety and Liveness ............... 9 3.4 Fairness is Machine Closure ..................... 10 3.5 Hiding is Existential Quantification ................ 10 3.6 Specification Methods that Don’t Work .............. 11 3.7 Specification Methods that Work for the Wrong Reason ..... 12 4 Other Methods ............................. 14 5 A Brief Advertisement for My Approach to State-Based Ver- ification and Specification of Concurrent Systems ....... 16 5.1 The Power of Formal Mathematics ................. 16 5.2Specifying Programs with Mathematical Formulas ........ 17 5.3 TLA ................................. -

Mount Litera Zee School Grade-VIII G.K Computer and Technology Read and Write in Notebook: 1

Mount Litera Zee School Grade-VIII G.K Computer and Technology Read and write in notebook: 1. Who is called as ‘Father of Computer’? a. Charles Babbage b. Bill Gates c. Blaise Pascal d. Mark Zuckerberg 2. Full Form of virus is? a. Visual Information Resource Under Seize b. Virtual Information Resource Under Size c. Vital Information Resource Under Seize d. Virtue Information Resource Under Seize 3. How many MB (Mega Byte) makes one GB (Giga Byte)? a. 1025 MB b. 1030 MB c. 1020 MB d. 1024 MB 4. Internet was developed in _______. a. 1973 b. 1993 c. 1983 d. 1963 5. Which was the first virus detected on ARPANET, the forerunner of the internet in the early 1970s? a. Exe Flie b. Creeper Virus c. Peeper Virus d. Trozen horse 6. Who is known as the Human Computer of India? a. Shakunthala Devi b. Nandan Nilekani c. Ajith Balakrishnan d. Manish Agarwal 7. When was the first smart phone launched? a. 1992 b. 1990 c. 1998 d. 2000 8. Which one of the following was the first search engine used? a. Google b. Archie c. AltaVista d. WAIS 9. Who is known as father of Internet? a. Alan Perlis b. Jean E. Sammet c. Vint Cerf d. Steve Lawrence 10. What us full form of GOOGLE? a. Global Orient of Oriented Group Language of Earth b. Global Organization of Oriented Group Language of Earth c. Global Orient of Oriented Group Language of Earth d. Global Oriented of Organization Group Language of Earth 11. Who developed Java Programming Language? a. -

The Specification Language TLA+

Leslie Lamport: The Speci¯cation Language TLA+ This is an addendum to a chapter by Stephan Merz in the book Logics of Speci¯cation Languages by Dines Bj¿rner and Martin C. Henson (Springer, 2008). It appeared in that book as part of a \reviews" chapter. Stephan Merz describes the TLA logic in great detail and provides about as good a description of TLA+ and how it can be used as is possible in a single chapter. Here, I give a historical account of how I developed TLA and TLA+ that explains some of the design choices, and I briefly discuss how TLA+ is used in practice. Whence TLA The logic TLA adds three things to the very simple temporal logic introduced into computer science by Pnueli [4]: ² Invariance under stuttering. ² Temporal existential quanti¯cation. ² Taking as atomic formulas not just state predicates but also action for- mulas. Here is what prompted these additions. When Pnueli ¯rst introduced temporal logic to computer science in the 1970s, it was clear to me that it provided the right logic for expressing the simple liveness properties of concurrent algorithms that were being considered at the time and for formalizing their proofs. In the early 1980s, interest turned from ad hoc properties of systems to complete speci¯cations. The idea of speci- fying a system as a conjunction of the temporal logic properties it should satisfy seemed quite attractive [5]. However, it soon became obvious that this approach does not work in practice. It is impossible to understand what a conjunction of individual properties actually speci¯es. -

Using Lamport Clocks to Reason About Relaxed Memory Models

Using Lamport Clocks to Reason About Relaxed Memory Models Anne E. Condon, Mark D. Hill, Manoj Plakal, Daniel J. Sorin Computer Sciences Department University of Wisconsin - Madison {condon,markhill,plakal,sorin}@cs.wisc.edu Abstract industrial product groups spend more time verifying their Cache coherence protocols of current shared-memory mul- system than actually designing and optimizing it. tiprocessors are difficult to verify. Our previous work pro- To verify a system, engineers should unambiguously posed an extension of Lamport’s logical clocks for showing define what “correct” means. For a shared-memory sys- that multiprocessors can implement sequential consistency tem, “correct” is defined by a memory consistency model. (SC) with an SGI Origin 2000-like directory protocol and a A memory consistency model defines for programmers the Sun Gigaplane-like split-transaction bus protocol. Many allowable behavior of hardware. A commonly-assumed commercial multiprocessors, however, implement more memory consistency model requires a shared-memory relaxed models, such as SPARC Total Store Order (TSO), a multiprocessor to appear to software as a multipro- variant of processor consistency, and Compaq (DEC) grammed uniprocessor. This model was formalized by Alpha, a variant of weak consistency. Lamport as sequential consistency (SC) [12]. Assume that This paper applies Lamport clocks to both a TSO and an each processor executes instructions and memory opera- Alpha implementation. Both implementations are based on tions in a dynamic execution order called program order. the same Sun Gigaplane-like split-transaction bus protocol An execution is SC if there exists a total order of memory we previously used, but the TSO implementation places a operations (reads and writes) in which (a) the program first-in-first-out write buffer between a processor and its orders of all processors are respected and (b) a read returns cache, while the Alpha implementation uses a coalescing the value of the last write (to the same address) in this write buffer. -

Should Your Specification Language Be Typed?

Should Your Specification Language Be Typed? LESLIE LAMPORT Compaq and LAWRENCE C. PAULSON University of Cambridge Most specification languages have a type system. Type systems are hard to get right, and getting them wrong can lead to inconsistencies. Set theory can serve as the basis for a specification lan- guage without types. This possibility, which has been widely overlooked, offers many advantages. Untyped set theory is simple and is more flexible than any simple typed formalism. Polymorphism, overloading, and subtyping can make a type system more powerful, but at the cost of increased complexity, and such refinements can never attain the flexibility of having no types at all. Typed formalisms have advantages too, stemming from the power of mechanical type checking. While types serve little purpose in hand proofs, they do help with mechanized proofs. In the absence of verification, type checking can catch errors in specifications. It may be possible to have the best of both worlds by adding typing annotations to an untyped specification language. We consider only specification languages, not programming languages. Categories and Subject Descriptors: D.2.1 [Software Engineering]: Requirements/Specifica- tions; D.2.4 [Software Engineering]: Software/Program Verification—formal methods; F.3.1 [Logics and Meanings of Programs]: Specifying and Verifying and Reasoning about Pro- grams—specification techniques General Terms: Verification Additional Key Words and Phrases: Set theory, specification, types Editors’ introduction. We have invited the following