Draft Water Allocation Plan for the River Murray Prescribed Watercourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overland Trails

Overland Trails Words: Miriam Blaker e arrived on dusk under a the years patrons of this historic pub have moody sky. Outside the hotel reported strange noises, old time fiddle music were stables, a lock-up and and unexplained goings on. According to the W wagons and I half expected current managers the hotel’s resident ghost a gun slinging bushranger to saunter out. is nicknamed ‘George’ and is a friendly ghost Originally an isolated frontier pub, the known to enjoy playing the jukebox. Overland Corner Hotel still has a feeling of Whether or not you believe in ghosts yesteryear with its walls of fossilised limestone the Overland Corner Hotel is a fascinating some 1.5 metres thick and floors lined with place. It’s just 700 metres from the Murray Clockwise from far left: pine and local red gum. Today it’s a popular River where rigs of all sizes can camp out Pelicans are constant visitors to Lake Bonney. Photo: Miriam Blaker. Banrock Station Wine and Wetland Centre. Photo: Miriam Blaker. The ruins of the old Lake Bonney Hotel. Photo: haunt for travellers who enjoy drover-sized the back of the hotel or down by the river, Miriam Blaker. Relaxing on the pier at Barmera. Photo: Doug Blaker. Exploring near the meals in a unique setting, a massive beer providing easy access to the delights of the historic Overland Corner. Photo: Miriam Blaker. garden, walls that just ooze history, a museum pub – just as the drovers would have done and a resident ghost. It’s a great place to enjoy years ago. -

Northern and Yorke Natural Resources Management Region

Department for Environment and Heritage Northern and Yorke Natural Resources Management Region Estuaries Information Package www.environment.sa.gov.au Contents Overview ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. What is an estuary? ................................................................................................................................. 3 3. Estuaries of the NY NRM region ............................................................................................................. 4 3.1 Estuary classification ......................................................................................................................... 4 3.2 Regional NRM groups ....................................................................................................................... 4 3.3 Coastal councils ............................................................................................................................... 4 4. Surface water, groundwater and marine areas .................................................................................. 8 4.1 Environmental flows .......................................................................................................................... 8 4.2 Groundwater influence................................................................................................................... -

River Health in the Mid North the Map Provides an Overall Assessment of the Health of Individual Sites in the Region

Mayfly nymph (Koorrnonga inconspicua) Aquatic macroinvertebrates in the Mid North The region is biologically diverse, with over 380 types of aquatic macroinvertebrates having been collected from 1994–1999. The most common members include amphipod crustaceans (e.g. Pseudomoera species and Austrochiltonia australis), blackfly larvae (Simulium ornatipes), oligochaetes (worms), chironomid midge larvae (Chironomus species), molluscs (hydrobiid snails) and nematodes (roundworms). A number of rare and uncommon macroinvertebrates are also found in the region. They include bristle worms (polychaete worms from the family Syllidae) found in the main channel of the Broughton River, as well as from the lower Rocky River and Mary Springs. These worms are normally found in marine and estuarine environments and their widespread presence in the Broughton catchment was unexpected. Other interesting records include horsehair worms (Gordiidae) from Skillogallee Creek, and planorbid snails (Gyraulus species) from the Light River at Mingays Waterhole. There are also three rare blackfly larvae that occur in the region: Austrosimulium furiosum from the Broughton River, Simulium melatum from Mary Springs and Paracnephia species from Belalie Creek. Among the rarer midges in the area are Podonomopsis from Eyre Creek, Apsectrotanypus from the Light River at Kapunda and Harrissius from the Wakefield River. Mayflies such as Offadens sp. 5 and Centroptilum elongatum, from the Broughton River and Mary Springs respectively, were unusual records, as were the presence of several caddisflies (e.g. Apsilochorema gisbum, Taschorema evansi, Orphninotrichia maculata and Lingora aurata) from Skillogallee and Eyre creeks, Mary Springs and the lower Broughton River. Mayfly nymphs (e.g. Koorrnonga inconspicua) have flattened bodies that allow them to cling to rocks in flowing streams. -

Murray and Mallee Local Government Association

MURRAY AND MALLEE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION. ANNUAL REPORT - 2003/2004. Comprising – The Berri Barmera Council; Coorong District Council; District Council of Karoonda East Murray; District Council of Loxton Waikerie; Mid Murray Council; The Rural City of Murray Bridge; Renmark Paringa Council; and Southern Mallee District Council. 2 PRESIDENT’S ANNUAL REPORT. Having been given the honour of being the President of the Murray & Mallee Local Government Association (M&MLGA) in June 2003, I would like to say a big thank you to those who served before me. The previous Mayor of Loxton-Waikerie, Jan Cass did a lot of work in her role as President of the M&MLGA and I would like to acknowledge her great contribution to our organization. We have been kept busy on the M&MLGA front with bimonthly meetings held in our Region that have been well supported by the member councils and we have enjoyed great communications from our LGA Executive. One of the main topics lately has been the Natural Resource Management Bill. We are all waiting to find out how it will all work and the input from State Executive has been great. Thank you. Ken Coventry has continued to serve the M&MLGA well as he organises all our guest speakers and represents us on a lot of other committees. He has, however, now indicated he wishes to retire as Chief Executive Officer of the M&MLGA and will stay in place until we appoint a new CEO. On behalf of the M&MLGA I would like to say a big thank you to Ken for his untiring work and dedication to his duty and he will be sorely missed. -

Minutes of Loxton High School Annual General

LOXTON HIGH SCHOL GOVERNING COUNCIL ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING MINUTES HELD ON TUESDAY 19 NOVEMBER 2019 AT 7.00PM @ LHS LIBRARY Meeting Opened: 7.05pm Welcome: Principal, Mr David Garrett and then handover to Mrs Margaret Wormald, current Governing Council chairperson to run meeting until executive positions declared vacant and election of new members. Acknowledgement of Country: We would like to acknowledge the custodians of the land and waters of the River Murray and Mallee Region. These clans comprise seven neighbouring groups known as the Ngaiawang, the Ngawait, the Ngaralte, the Ngarkat, the Ngagkuruku, the Ngintait and the Erawirung. These clans were one nation. Today we are meeting on the traditional lands of the Erawirung people and we feel welcome. Present: David Garrett, Tom Fielke Apologies: Leanne Priest, Shannon Tootell, Scott Gillett, Jill Obst Minutes of Previous Meeting: Held on 20 November 2018 at 7.00pm. Moved and seconded: Moved Kerry Albrecht-Szabo, Seconded Shannon Tootell Carried Reports: 1. Principal’s Report – Mr David Garrett. Moved by Julie-ann Phillips and seconded by Mel Morena Carried 2. High School Governing Council Chairman’s Report – Mr Tom Fielke Moved by Kerry Albrecht and seconded by Scott Gillett Carried 3. Financial Statements – Ms Lesley Peterson • Loxton High School Council Inc. Consolidated Account • Loxton High School Canteen Trading Statement • Motion to accept the 2020 budget as an interim budget with final budget to be handed down in March 2020 Lesley advised accounts are still subject to Audit. Statements attached. All Financial Statements Moved by Lesley Peterson and seconded by Scott Gillett Carried Elections: Principal, David Garrett to hold election (if necessary) Election of Governing Council Members Those remaining on Council: Rebecca Knowles, Melinda Morena, Tom Fielke, Kylie O’Shaughnessy, Ian Schneider. -

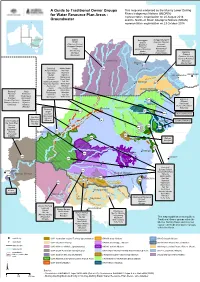

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups For

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Th is m ap w as e nd orse d by th e Murray Low e r Darling Rive rs Ind ige nous Nations (MLDRIN) for Water Resource Plan Areas - re pre se ntative organisation on 20 August 2018 Groundwater and th e North e rn Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) re pre se ntative organisation on 23 Octobe r 2018 Bidjara Barunggam Gunggari/Kungarri Budjiti Bidjara Guwamu (Kooma) Guwamu (Kooma) Bigambul Jarowair Gunggari/Kungarri Euahlayi Kambuwal Kunja Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Mandandanji Mandandanji Murrawarri Giabel Bigambul Mardigan Githabul Wakka Wakka Murrawarri Githabul Guwamu (Kooma) M Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a r a Kambuwal !(Charleville n o Ro!(ma Mandandanji a GW21 R i «¬ v Barkandji Mutthi Mutthi GW22 e ne R r i i «¬ am ver Barapa Barapa Nari Nari d on Bigambul Ngarabal C BRISBANE Budjiti Ngemba k r e Toowoomba )" e !( Euahlayi Ngiyampaa e v r er i ie Riv C oon Githabul Nyeri Nyeri R M e o r Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Tati Tati n o e i St George r !( v b GW19 i Guwamu (Kooma) Wadi Wadi a e P R «¬ Kambuwal Wailwan N o Wemba Wemba g Kunja e r r e !( Kwiambul Weki Weki r iv Goondiwindi a R Barkandji Kunja e GW18 Maljangapa Wiradjuri W n r on ¬ Bigambul e « Kwiambul l Maraura Yita Yita v a r i B ve Budjiti Maljangapa R i Murrawarri Yorta Yorta a R Euahlayi o n M Murrawarri g a a l rr GW15 c Bigambul Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngarabal u a int C N «¬!( yre Githabul R Guwamu (Kooma) Ngemba iv er Kambuwal Kambuwal Wailwan N MoreeG am w Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wiradjuri o yd Barwon River i R ir R Kwiambul !(Bourke iv iv Barkandji e er GW13 C r GW14 Budjiti -

Water Allocation Plan for the RIVER MURRAY PRESCRIBED WATERCOURSE

This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Natural Resources Management Board. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Regional Director, Natural Resources SA Murray-Darling Basin, PO Box 2343, Murray Bridge SA 5253. The South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Natural Resources Management Board and the Government of South Australia, their employees and their servants do not warrant, or make any representation, regarding the use or results of the information contain herein as to its correctness, accuracy, currency or otherwise. The South Australian Murray-Darling Basin Natural Resources Management Board and the Government of South Australia, their employees and their servants expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice herein. Aboriginal Cultural Knowledge No authority is provided by First Peoples of the River Murray and Mallee, Peramangk and Ngarrindjeri nations for the use of their cultural knowledge contained in this document without their prior written consent. ii Water Allocation Plan FOR THE RIVER MURRAY PRESCRIBED WATERCOURSE iii iv v Acknowledgement The South Australian Government acknowledges and respects Aboriginal people as the state’s first peoples and nations, and recognises Aboriginal people as traditional owners and occupants of land and waters in South Australia. Aboriginal peoples’ spiritual, social, cultural and economic practices come from their lands and waters, and they continue to maintain their cultural heritage, economies, languages and laws which are of ongoing importance. -

Ngarkat Complex of Conservation Parks Management Plan

Ngarkat Complex of Conservation Parks Management Plan This plan of management has been prepared and adopted in pursuance of Section 38 of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972. Published by the Department for Environment and Heritage, Adelaide, Australia Department for Environment and Heritage, 2004 ISBN: 0 75901076 5 Final Edited by staff of Mallee District and Reserve Planning Department for Environment and Heritage Cartography by Reserve Planning and Benno Curth Cover photo clockwise from top left: Silvery phebalium Phabalium bullatum, Little Pygmy Possum Cercartetus lepidus on Leptospermum spp, Silver Goodenia Goodenia willisiana, Mallee Heath, Wallowa Acacia calamifolia, Malleefowl Leipoa ocellata, Mallee Heath and Western Blutongue Tiliqua occipitalis. This document may be cited as ‘Department for Environment and Heritage (2004) Ngarkat Complex of Conservation Parks Management Plan, Adelaide, South Australia’ FIS 17148 •Feb 2004 Department for Environment and Heritage Ngarkat Complex of Conservation Parks Incorporating Ngarkat, Mt Rescue, Mt Shaugh and Scorpion Springs Conservation Parks Management Plan March 2004 Our Parks, Our Heritage, Our Legacy Cultural richness and diversity are the marks of a great society. It is these qualities that are basic to our humanity. They are the foundation of our value systems and drive our quest for purpose and contentment. Cultural richness embodies morality, spiritual well-being, the rule of law, reverence for life, human achievement, creativity and talent, options for choice, a sense of belonging, personal worth and an acceptance of responsibility for the future. Biological richness and diversity are, in turn, important to cultural richness and communities of people. When a community ceases to value and protect its natural landscapes, it erodes the richness and wholeness of its cultural foundation. -

A Snapshot of the Tailem Bend Community Centre Murray Mallee Community Passenger Network

TAILEM BENDCommunity CENTRE INC. A Snapshot of The Tailem Bend Community Centre Murray Mallee Community Passenger Network Providing social interaction, lifelong learning opportunities and transport for the Murraylands community. Tailem Bend Community Centre Snapshot 2019 1 TAILEM BENDCommunity CENTRE INC. Tailem Bend Community Centre (TBCC) Quick Stats Location: Tailem Bend, South Australia (Coorong District Council LGA region) Service Area: Tailem Bend and Murraylands surrounds Employed Staff: 4 staff 2.8 FTE and a contract cleaner Volunteers: 40 Volunteer Hours: 3,136.4 (2017/87) Members: 250 Participants: 300 per month or 3,500 per year CHSP/HACC (Meals) 571 (2017/18) Facilities: Function room (fully equipped), various outbuildings for classes Commercial kitchen and facilities for hire, catering services, community bus hire, medical bus brokerage and community passenger Network Administrative services Activities: Social Support classes 20 per week I.e. exercise, sewing, IT, craft, woodworking, mosaics, leadlight Evidence Based programs for parents/kids -Our Time Parent Child Mother Goose, Tuning into Kids, Seasons for Growth, Drumbeat. Kids activities School term and holiday fun activities and events Transport medical bus and community passenger network Access to Centrelink internet and services Support services advocacy, Food Bank support Community garden and Grow Free produce sharing cart Programs: Commonwealth Home Support Programme (CHSP) ▪ Our Goldie’s meals & transport ▪ Social Support group & individual – i.e. classes, trips -

There Has Been an Italian Presence in the Riverland Since

1 Building blocks of settlement: Italians in the Riverland, South Australia By Sara King and Desmond O’Connor The Riverland region is situated approximately 200 km. north-east of Adelaide and consists of a strip of land on either side of the River Murray from the South Australian-Victorian border westwards to the town of Morgan. Covering more than 20,000 sq. km., it encompasses the seven local government areas of Barmera, Berri, Loxton, Morgan, Paringa, Renmark and Waikerie.1 The region was first identified as an area of primary production in 1887 when two Canadian brothers, George and William Chaffey, were granted a licence to occupy 101,700 hectares of land at Renmark in order to establish an irrigated horticultural scheme. By 1900 a prosperous settlement had developed in the area for the production of vines and fruit, and during the 1890s Depression other ‘village settlements’ were established down river by the South Australian Government to provide work for the city-based unemployed.2 During the years between the foundation of the villages and the First World War there was intense settlement, especially around Waikerie, Loxton, Berri and Barmera, as the area was opened up and increased in value.3 After World War 1, the SA Government made available new irrigation blocks at Renmark and other localities in the Riverland area to assist the resettlement of more than a thousand returned soldiers. A similar scheme operated in New South Wales, where returned servicemen were offered blocks in Leeton and Griffith, in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area.4 The period after World War 2 saw further settlement of returned soldiers on fruit blocks in the Riverland and new irrigation areas were developed to cater for this growth. -

Sent" Austria.I

74 THE S.A. ORNITHOLOGIST July, 1955 ABORIGINAL BIRD NAMES - SOUTH AUSTRALIA Part One By H. T. CONDON, S.A. Museum According to Tindale (1940), at the time considerable number of references to pub- of the first white settlement there were about lished works. In every case the tabulations fifty aboriginal tribes whose territories were (made by writers in all walks of life) have within or" entered the boundaries of what is been checked against known occurrences of now the State of South Australia (fig. 1). the species concerned or mentioned, and a No natives were living on Kangaroo Island, successful attempt has also been made to although relics of human occupation at some identify the maj ority of the numerous vague remote period have since been found. The and descriptive records by writers who had task of recording the vocabularies of the little knowledge of birds. The usual method tribes was commenced almost at once- by the employed by recorders has been to write the settlers, and the literature concerning the native words in a way resembling the English language of the natives is now large and language, and these original spellings (of comprehensive. Information concerning the which there are many variations) have been names used for the birds is widely scattered retained. Certain authors used a phonetic and I am indebted to my colleagues, Messrs. system of some kind and the following list H. M. Cooper and N. B. Tindale, for a therefore contains a mixture of words con- .. Sent" Austria.i. Fig. 1 July, 1955 THE S.A. -

Murray & Mallee LGA Regional Public Health

Acknowledgements This report has been prepared for The Murray Mallee LGA by URS and URPS. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the following members of the Steering Group: Public Health Plan Steering Committee - Gary Brinkworth, Berri Barmera Council - Jim Quinn, Coorong District Council - Stephen Bateman, District Council of Loxton Waikerie - Kevin Goldstone and Caroline Thomas, Mid Murray Council - Katina Nikas, Renmark Paringa Council - Clarry Fisher and Phil Eckert, Rural City of Murray Bridge - Harc Wordsworth, Southern Mallee District Council (also representing District Council of Karoonda East Murray) Cover photos courtesy of Paul White, Loxton Waikerie Council and Bianca Gazzola, Mid Murray Council Contents President’s Message 1 Executive Summary 2 1 Introduction 4 2 What determines Health and Wellbeing? 5 3 Legislative Context 6 South Australian Public Health Act 2011 Local Government Act 1999 4 Policy Context 7 South Australian Public Health Plan Other Strategies and Policies Specified by the Minister 5 The Murray and Mallee Local Government Region 8 6 Developing the Public Health Plan 9 7 Assessment of the State of Health 11 Factors that Influence Health Risks to Health Burden of Disease Summary of the State of Health Priorities for the Region 8 Audit of Existing Plans, Policies and Initiatives- Summary of Outcomes 19 Audit of existing initiatives (gaps and opportunities) Common themes for regional action 9 Strategies for Promoting Health 21 Stronger, Healthier Communities for all generations Increasing Opportunities