The Greening of Water Law: Managing Freshwater Resources for People and the Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clarifying State Water Rights and Adjudications

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Two Decades of Water Law and Policy Reform: A Retrospective and Agenda for the Future 2001 (Summer Conference, June 13-15) 6-14-2001 Clarifying State Water Rights and Adjudications John E. Thorson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/water-law-and-policy-reform Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Environmental Law Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, State and Local Government Law Commons, Sustainability Commons, Water Law Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Citation Information Thorson, John E., "Clarifying State Water Rights and Adjudications" (2001). Two Decades of Water Law and Policy Reform: A Retrospective and Agenda for the Future (Summer Conference, June 13-15). https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/water-law-and-policy-reform/10 Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law Center) at the University of Colorado Law School. John E. Thorson, Clarifying State Water Rights and Adjudications, in TWO DECADES OF WATER LAW AND POLICY REFORM: A RETROSPECTIVE AND AGENDA FOR THE FUTURE (Natural Res. Law Ctr., Univ. of Colo. Sch. of Law, 2001). Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law Center) at the University of Colorado Law School. CLARIFYING STATE WATER RIGHTS AND ADJUDICATIONS John E. Thorson Attorney-at-Law & Water Policy Consultant Oakland, California [Formerly Special Master (1990-2000) Arizona General Stream Adjudication] Two Decades of Water Law and Policy Reform: A Retrospective and Agenda for the Future June 13-15, 2001 NATURAL RESOURCES LAW CENTER University of Colorado School of Law Boulder, Colorado CLARIFYING STATE WATER RIGHTS AND ADJUDICATIONS John E. -

A Buyer's Guide to Montana Water Rights

A Buyer’s Guide To Montana Water Rights By Stan Bradshaw Trout Unlimited, Montana Water Project A Cautionary Tale his tale is based on real events. I’ve just changed the names, details of the water right, the specific facts of the dispute, T and the location to avoid undue embarrassment to anyone. In 2002, Michael Hartman looked at a ranch for sale on a major tributary in the upper Missouri river basin. It was 1100 acres with frontage on a trout stream, and it had an active sprinkler-irrigated hay operation on 160 acres. When Hartmann was negotiating the deal, the realtor produced a water rights document entitled “Statement of Existing Water Right Claim” (“Statement of Claim” for our purposes). It included a water right number, identified a flow rate of 10 cubic feet per second (cfs), and 320 irrigated acres, complete with a legal description of the acres irrigated. It seemed like a great deal—nice property right on a famous trout stream, and a whole lot of water rights to work with. What’s not to like? So he bought it. After moving on to the land, Hartman looked at the acres claimed for irrigation in the Statement of Claim, located the 160 acres that weren’t currently being irrigated, and embarked on plans to start irrigating them. When he walked the land, he didn’t notice any sign of ditches or headgates on the quarter section he wanted to irrigate, but he figured, “Hey, it’s listed on the water right, so I have the water for it.” He approached the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) about cost sharing a new center pivot on the land and putting a pump into the ditch serving the other 160 acres, and they seemed interested. -

The Economic Conception of Water

CHAPTER 4 The economic conception of water W. M. Hanemann University of California. Berkeley, USA ABSTRACT: This chapterexplains the economicconception of water -how economiststhink about water.It consistsof two mainsections. First, it reviewsthe economicconcept of value,explains how it is measured,and discusses how this hasbeen applied to waterin variousways. Then it considersthe debate regardingwhether or not watercan, or should,be treatetlas aneconomic commodity, and discussesthe ways in which wateris the sameas, or differentthan, other commodities from aneconomic point of view. While thereare somedistinctive emotive and symbolic featuresof water,there are also somedistinctive economicfeatures that makethe demandand supplyof water different and more complexthan that of most othergoods. Keywords: Economics,value ofwate!; water demand,water supply,water cost,pricing, allocation INTRODUCTION There is a widespread perception among water professionals today of a crisis in water resources management. Water resources are poorly managed in many parts of the world, and many people -especially the poor, especially those living in rural areasand in developing countries- lack access to adequate water supply and sanitation. Moreover, this is not a new problem - it has been recognized for a long time, yet the efforts to solve it over the past three or four decadeshave been disappointing, accomplishing far less than had been expected. In addition, in some circles there is a feeling that economics may be part of the problem. There is a sense that economic concepts are inadequate to the task at hand, a feeling that water has value in ways that economics fails to account for, and a concern that this could impede the formulation of effective approaches for solving the water crisis. -

OVERVIEW of INDONESIA WATER SYSTEM and POLICIES1 Ir

OVERVIEW OF INDONESIA WATER SYSTEM AND POLICIES1 Ir. M. Donny Azdan, MA., MS., Ph.D2 I. WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT REFORM Water resources management reform which is characterized by the enactment of Law No.7/2004 on Water Resources is intended to anticipate the complexity of water resources development problems and shifting in water resources management paradigm by giving more attention to social functions, environment and economy that is directed to achieve the synergic and harmonic integration of interregional, intersectoral, and intergenerational. Reformation started with the formation of the coordination team of Water Resources Management (TKPSDA) in 2001 in charge of formulating national policies on water resources and various policy tools, as well as encouraging the establishment of the new Water Resources Law. In line with the spirit of democratization, decentralization and openness, fundamental reforms in the Law of No.7/2004 is that the three main pillars of water resource management in the previous Law No.11/1974 which consists of the conservation, utilization and control of destructive force, is supported by three other pillars of community participation, steady institutional and good information systems and data. Principles of water resources management policies, which are contained in the Law of No. 7/2004 are derived into seven government regulations (GR)3, namely Water Resources Management, Irrigation, Development of Drinking Supply System (SPAM), Ground Water, Dams, Rivers, and Swamp. Until the year of 2011, the government has published six regulations except for regulation on swamp4. Principles of water resources reform through Law of No.7/2004 are: 1. Clarity of water resources management responsibilities between central and regional In accordance with the Law No.7/2004, water resources management is conducted based on river basin. -

A Future History of Water

a future history of water Future History a Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 of Water Andrea Ballestero © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Chaparral Pro by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Ballestero, Andrea, [date] author. Title: A future history of water / Andrea Ballestero. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2018047202 (print) | lccn 2019005120 (ebook) isbn 9781478004516 (ebook) isbn 9781478003595 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478003892 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Water rights—Latin America. | Water rights—Costa Rica. | Water rights—Brazil. | Right to water—Latin America. | Right to water—Costa Rica. | Right to water—Brazil. | Water-supply— Political aspects—Latin America. | Water-supply—Political aspects— Costa Rica. | Water-supply—Political aspects—Brazil. Classification:lcc hd1696.5.l29 (ebook) | lcc hd1696.5.l29 b35 2019 (print) | ddc 333.33/9—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047202 Cover art: Nikolaus Koliusis, 360°/1 sec, 360°/1 sec, 47 wratten B, 1983. Photographer: Andreas Freytag. Courtesy of the Daimler Art Collection, Stuttgart. This title is freely available in an open access edition thanks to generous support from the Fondren Library at Rice University. para lioly, lino, rómulo, y tía macha This page intentionally left blank contents ix preface -

Impression Series® Impression Plus Series® Water Filters TABLE of CONTENTS

Impression Series® Impression Plus Series® Water Filters TABLE OF CONTENTS Pre-Installation Instructions for Dealers . 3 Bypass Valve . 4 Installation . 5-7 Programming Procedures . 8 Startup Instructions . 9 Operating Displays and Instructions . 10-11 Replacement Mineral Instructions for Acid Neutralizers . 12 Troubleshooting Guide . 13-16 Replacement Parts . 17-24 Specifications . 25-26 Warranty . 27 Quick Reference Guide . 28 YOUR WATER TEST Hardness _________________________ gpg Iron ______________________________ ppm pH _______________________________ number *Nitrates __________________________ ppm Manganese _______________________ ppm Sulphur ___________________________ yes/no Total Dissolved Solids _______________ *Over 10 ppm may be harmful for human consumption . Water conditioners do not remove nitrates or coliform bacteria, this requires specialized equipment . Your Impression Series water filters are precision built, high quality products . These units will deliver filtered water for many years to come, when installed and operated properly . Please study this manual carefully and understand the cautions and notes before installing . This manual should be kept for future reference . If you have any questions regarding your water softener, contact your local dealer or Water-Right at the following: Water-Right, Inc. 1900 Prospect Court • Appleton, WI 54914 Phone: 920-739-9401 • Fax: 920-739-9406 PRE-INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS FOR DEALERS The manufacturer has preset the water treatment unit’s sequence of cycles and cycle times . The dealer should read this page and guide the installer regarding hardness, day override, and time of regeneration, before installation. For the installer, the following must be used: • Program Installer Settings: Day Override (preset to 3 days) and Time of Regeneration (preset to 12 a .m .) • Read Normal Operating Displays • Set Time of Day • Read Power Loss & Error Display For the homeowner, please read sections on Bypass Valve and Operating Displays and Maintenance . -

Water: Economics and Policy 2021 – ECI Teaching Module

Water: Economics and Policy By Brian Roach, Anne-Marie Codur and Jonathan M. Harris An ECI Teaching Module on Social and Environmental Issues in Economics Global Development Policy Center Boston University 53 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02155 bu.edu/gdp WATER: ECONOMICS AND POLICY Economics in Context Initiative, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University, 2021. Permission is hereby granted for instructors to copy this module for instructional purposes. Suggested citation: Roach, Brian, Anne-Marie Codur, and Jonathan M. Harris. 2021. “Water: Economics and Policy.” An ECI Teaching Module on Social and Economic Issues, Economics in Context Initiative, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University. Students may also download the module directly from: http://www.bu.edu/eci/education-materials/teaching-modules/ Comments and feedback from course use are welcomed: Economics in Context Initiative Global Development Policy Center Boston University 53 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02215 http://www.bu.edu/eci/ Email: [email protected] NOTE – terms denoted in bold face are defined in the KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS section at the end of the module. 1 WATER: ECONOMICS AND POLICY TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. GLOBAL SUPPLY AND DEMAND FOR WATER.................................................... 3 1.1 Water Demand, Virtual Water, and Water Footprint ................................................. 8 1.2 Virtual Water Trade ................................................................................................. 11 1.3 Water Footprint the Future of Water: -

Florida's Ground Water: Legal Problems in Managing a Precious Resource

University of Miami Law Review Volume 21 Number 4 Article 2 7-1-1967 Florida's Ground Water: Legal Problems in Managing a Precious Resource Frank E. Maloney Sheldon J. Plager Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation Frank E. Maloney and Sheldon J. Plager, Florida's Ground Water: Legal Problems in Managing a Precious Resource, 21 U. Miami L. Rev. 751 (1967) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol21/iss4/2 This Leading Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA'S GROUND WATER: LEGAL PROBLEMS IN MANAGING A PRECIOUS RESOURCEf FRANK E. MALONEY* AND SHELDON J. PLAGER** I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 752 II. HYDROLOGY AND GEOLOGY OF GROUND WATER .............................. 752 A . H ydrology .......................................................... 752 B. Geology-The Aquifers in Florida ..................................... 756 III. GROUND WATER PROBLEMS ............................................... 757 A. Interference Between W ells ........................................... 758 B. Overdraft of the Water-Bearing Bed or Aquifer ........................ 759 C. Contamination ..................................................... -

Berlin Rules on Water Resources

1 INTERNATIONAL LAW ASSOCIATION BERLIN CONFERENCE (2004) WATER RESOURCES LAW Members of the Committee: Dr Gerhard Loibl (Austria): Chair Professor Joseph W Dellapenna (USA): Rapporteur Professor Malgosia Fitzmaurice (UK): Secretary Dr Slavko J Bogdanovic (HQ) Professor Frank Maes (Belgium-Luxembourg) Professor Charles B Bourne (Canada) HE Ambassador A K H Morshed (Bangladesh) Dr Janos Bruhacs (Hungary) Professor Andre Nollkaemper (Netherlands) Dr Stefano Burchi (Italy) Professor Kazimierz Rowny (Poland) Professor Paulo Canelas de Castro (HQ) HE Ambassador Robbie Sabel (Israel) Dr L Del Castillo de Laborde (Argentina) Dr Salman Salman (HQ) Mr Anil B Divan (India) Professor Surya P Subedi (UK) H E Ambassador Aziza Fahmi (HQ) Professor Christoph Vedder (Germany) Professor Robert D Hayton (USA) Dr Patricia Wouters (Canada) Dr Harald Hohmann (Germany) Consultants: Professor Alan E Boyle (UK) Ms Kerstin Mechlem (Germany) FOURTH REPORT PART ONE The Water Resources Committee presented its first report at the 1996 Helsinki Conference of the As- sociation. At that time, the Association, on the recommendation of WRC, adopted two sets of articles, namely the Articles on Private Law Remedies for Transboundary Damage in International Watercourses and the Supplemental Rules on Pollution. The Association also approved the Resolution proposed by the Water Resources Committee on the Further Consideration by the General Assembly of the United Nations of the Draft Articles on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses proposed by the International Law Commission, and requested the Secretary General of the Association to transmit the Resolution to the Secretary General of the United Nations Organization with the suggestion that it be circu- lated to members of the Organization. -

Water Right – Conserving Our Water, Preserving Our Environment

WATER RIGHT Conserving Our Water Preserving Our Environment Preface WATER Everywhere Dr. H. Marc Cathey It has many names according to how our eyes experi- and recycle water for our plantings and landscape – ence what it can do. We call it fog, mist, frost, clouds, among which, the lawn is often the most conspicuous sleet, rain, snow, hail and user of water. condensate. It is the one Grasses and the surround- compound that all space ing landscape of trees, explorers search for when shrubs, perennials, food they consider the coloniza- plants, herbs, and native tion of a new planet. It is plants seldom can be left to the dominant chemical in the fickleness of available all life forms and can rainfall. With landscaping make almost 99 percent of estimated to contribute an organism’s weight. It approximately 15 percent is also the solvent in to property values, a We call it fog, mist, frost, clouds, sleet, rain, snow and condensation. which all synthesis of new Water is the earth’s primary chemical under its greatest challenge responsible management compounds––particularly • decision would be to make sugars, proteins, and fats––takes This volume provides the best of all water resources. place. It is also the compound that assurance to everyone that the We are fortunate that the techno- is split by the action of light and quality of our environment will logy of hydroponics, ebb and flow, chlorophyll to release and repeat- not be compromised and we can look forward to years of and drip irrigation have replaced edly recycle oxygen. -

The Local and National Politics of Groundwater Overexploitation

www.water-alternatives.org Volume 11 | Issue 3 Molle, F.; López-Gunn, E. and van Steenbergen, F. 2018. The local and national politics of groundwater overexploitation. Water Alternatives 11(3): 445-457 The Local and National Politics of Groundwater Overexploitation François Molle UMR G-Eau, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), Univ Montpellier, France; [email protected] Elena López-Gunn I-CATALIST, S.L., Madrid, Spain; and Visiting Fellow, University of Leeds, UK; [email protected] Frank van Steenbergen MetaMeta Research, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Groundwater overexploitation is a worldwide phenomenon with important consequences and as yet few effective solutions. Work on groundwater governance often emphasises the roles of both formal state- centred policies and tools on the one hand, and self-governance and collective action on the other. Yet, empirically grounded work is limited and scattered, making it difficult to identify and characterise key emerging trends. Groundwater policy making is frequently premised on an overestimation of the power of the state, which is often seen as incapable or unwilling to act and constrained by a myriad of logistical, political and legal issues. Actors on the ground either find many ways to circumvent regulations or develop their own bricolage of patched, often uncoordinated, solutions; whereas in other cases corruption and capture occur, for example in water right trading rules, sometimes with the complicity – even bribing – of officials. Failed regulation has a continued impact on the environment and the crowding out of those lacking the financial means to continue the race to the bottom. Groundwater governance systems vary widely according to the situation, from state-centred governance to co- management and rare instances of community-centred management. -

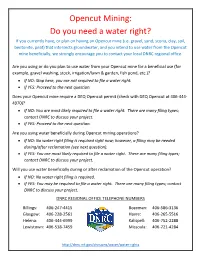

DNRC-Opencut Mining: Do You Need a Water Right?

Opencut Mining: Do you need a water right? If you currently have, or plan on having an Opencut mine (i.e. gravel, sand, scoria, clay, soil, bentonite, peat) that intersects groundwater, and you intend to use water from the Opencut mine beneficially, we strongly encourage you to contact your local DNRC regional office. Are you using or do you plan to use water from your Opencut mine for a beneficial use (for example, gravel washing, stock, irrigation/lawn & garden, fish pond, etc.)? • If NO: Stop here, you are not required to file a water right. • If YES: Proceed to the next question. Does your Opencut mine require a DEQ Opencut permit (check with DEQ Opencut at 406-444- 4970)? • If NO: You are most likely required to file a water right. There are many filing types; contact DNRC to discuss your project. • If YES: Proceed to the next question. Are you using water beneficially during Opencut mining operations? • If NO: No water right filing is required right now; however, a filing may be needed during/after reclamation (see next question). • If YES: You are most likely required to file a water right. There are many filing types; contact DNRC to discuss your project. Will you use water beneficially during or after reclamation of the Opencut operation? • If NO: No water right filing is required. • If YES: You may be required to file a water right. There are many filing types; contact DNRC to discuss your project. DNRC REGIONAL OFFICE TELEPHONE NUMBERS Billings: 406-247-4415 Bozeman: 406-586-3136 Glasgow: 406-228-2561 Havre: 406-265-5516 Helena: 406-444-6999 Kalispell: 406-752-2288 Lewistown: 406-538-7459 Missoula: 406-721-4284 http://dnrc.mt.gov/divisions/water/water-rights .