AUSTRALIA NOTES for READING GROUPS Michael Mcgirr BYPASS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outer Sydney Orbital, Bells Line of Road Castlereagh Connection And

Corridor Preservation Outer Sydney Orbital Bells Line of Road - Castlereagh Connection South West Rail Link Extension July 2015 Long term transport master plan The Bells Line of Road – Castlereagh Connection, The Outer Sydney Orbital and the South West Rail Link Extension are three of the 19 major transport corridors identified across Sydney for preservation for future transport use. The corridors would provide essential cross-regional connections with access to the growth centres and the Broader Western Sydney Employment Area with connections to the Western Sydney Airport. 2 Bells line of Road – Castlereagh Connection study area The Bells Line of Road – Castlereagh Connection (BLoR - CC) is a corridor to provide a connection from Kurrajong to Sydney’s motorway network, and provide an alternate route across the Blue Mountains. Preservation of a corridor for BLoR – CC was a recommendation of the Bells Line of Road Long Term Strategic Corridor Plan. 3 Outer Sydney Orbital study area OSO is a multi-modal transport corridor connecting the Hunter and Illawarra region. Stage 1 – from the Hume Highway to Windsor Road, approximately 70km comprising of a: • Motorway with interchanges with major east/west roads • Freight corridor with connections to the main western rail line and a potential IMT • Where practical passenger rail The Outer Sydney Orbital is also included in: • NSW Freight and Ports Strategy • NSW State Infrastructure Strategy • The Broader Western Sydney Employment Area draft Structure Plan The Outer Sydney Orbital three stage approach includes: Study stage 1. Hume Motorway & main Southern Rail Line to Windsor Rd 2. Hume Motorway and main Southern Rail to Illawarra 3. -

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’S Guide

New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Important: This Operator’s Guide is for three Notices separated by Part A, Part B and Part C. Please read sections carefully as separate conditions may apply. For enquiries about roads and restrictions listed in this document please contact Transport for NSW Road Access unit: [email protected] 27 October 2020 New South Wales Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicle Operator’s Guide Contents Purpose ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 NSW Travel Zones .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Part A – NSW Class 1 Load Carrying Vehicles Notice ................................................................................................ 9 About the Notice ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 1: Travel Conditions ................................................................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Pilot and Escort Requirements .......................................................................................................................... -

MEDIA STATEMENT 29 July 2019 Australia's Major Highway Now a Conveyor Belt for Big Trucks

MEDIA STATEMENT 29 July 2019 Media contact: Paul Hitchins 0419 315 001 Australia’s major highway now a conveyor belt for big trucks 700,000 B-double truck trips on Hume Highway each year Rail freight on its deathbed between Melbourne & Sydney In a disturbing development, Australia’s largest rail freight operator, Pacific National has declared rail freight is on its deathbed between Melbourne and Sydney. Pacific National CEO Dean Dalla Valle said less than 1 per cent of 20-million tonnes of palletised and containerised freight transported between Melbourne and Sydney is now hauled by trains. “Australia’s busiest freight corridor by volume has become a conveyor belt of 700,000 B-double equivalent return truck trips each year along the Hume Highway1,” said Mr Dalla Valle. Mr Dalla Valle said excessive government charges applied to rail freight services and a build-up of red tape2 is suffocating the haulage of goods by rail between Australia’s two biggest cities. “Bizarrely, at a time when Australians want safer roads, less traffic congestion during their daily commute3, reduced vehicle emissions, and properly maintained roads4, government policies are geared to rolling out bigger and heavier trucks5 on more roads,” said Mr Dalla Valle. A 2016 report by Australian Automobile Association ranked sections of the Hume Highway as some of the nation’s most dangerous roads6, while a 2017 Deloitte Access Economics report found, for every tonne of freight hauled a kilometre, trucks produce 14 times greater accident costs than trains7. Mr Dalla Valle said trucks may not be the root cause of most accidents, but the sheer size, weight and momentum of a truck crashing with a car often results in casualties or fatalities. -

The Old Hume Highway History Begins with a Road

The Old Hume Highway History begins with a road Routes, towns and turnoffs on the Old Hume Highway RMS8104_HumeHighwayGuide_SecondEdition_2018_v3.indd 1 26/6/18 8:24 am Foreword It is part of the modern dynamic that, with They were propelled not by engineers and staggering frequency, that which was forged by bulldozers, but by a combination of the the pioneers long ago, now bears little or no needs of different communities, and the paths resemblance to what it has evolved into ... of least resistance. A case in point is the rough route established Some of these towns, like Liverpool, were by Hamilton Hume and Captain William Hovell, established in the very early colonial period, the first white explorers to travel overland from part of the initial push by the white settlers Sydney to the Victorian coast in 1824. They could into Aboriginal land. In 1830, Surveyor-General not even have conceived how that route would Major Thomas Mitchell set the line of the Great look today. Likewise for the NSW and Victorian Southern Road which was intended to tie the governments which in 1928 named a straggling rapidly expanding pastoral frontier back to collection of roads and tracks, rather optimistically, central authority. Towns along the way had mixed the “Hume Highway”. And even people living fortunes – Goulburn flourished, Berrima did in towns along the way where trucks thundered well until the railway came, and who has ever through, up until just a couple of decades ago, heard of Murrimba? Mitchell’s road was built by could only dream that the Hume could be convicts, and remains of their presence are most something entirely different. -

Great Western Highway Upgrade Program Project Benefits Fact Sheet October 2020

Transport for NSW Great Western Highway Upgrade Program Project benefits fact sheet October 2020 The upgrade program will reduce congestion and improve safety on the highway The NSW Government is investing $2.5 billion towards upgrading the Great Western Highway between Katoomba and Lithgow to a four lane carriageway. Once completed, the upgrade will reduce congestion and deliver safer, more efficient and reliable journeys for those travelling in, around and through the Blue Mountains, while also better connecting communities in the Central West. The Great Western Highway Upgrade Program • Enhance liveability and amenity: aims to: maintain and improve local amenity and • Improve safety: reducing safety risks along character, and protect environmental the corridor for all road users and cultural assets • Improve network performance: improve • Improve resilience and future proof: provide congestion and travel time reliability a dependable and adaptable transport network that enables continuity of transport • Improve and drive regional economic and essential services. development and productivity nswroads.work/greatwesternhighway Page 1 of 4 Improve safety Improve network performance The upgrade program aims to reduce crash The Great Western Highway is a key corridor rates between Katoomba and Lithgow, which of national significance and has rising traffic are currently higher than the NSW average for volumes. The daily average traffic volume similar roads. entering/exiting Blackheath is more than Transport for NSW has recorded a 77% 16,000 vehicles. reduction in fatal crashes and a 28% This volume is greater than the daily volumes reduction in casualties between Leura and on already duplicated highways such as the Warrimoo since the highway was duplicated Hume Highway at Goulburn, the Princes and upgraded. -

Regional and Interstate Transport Summary 10.1 Snapshot • Regional and Interstate Transport Infrastructure • a Number of Major Road Programs Are Underway

10.0 Regional and interstate transport Summary 10.1 Snapshot • Regional and interstate transport infrastructure • A number of major road programs are underway. • Long distances, low population densities and the supports the economy and quality of life of These include upgrades to the Pacific Highway nature of regional employment means the demands NSW by allowing people to access employment and Princes Highway. Getting the best value for placed by passengers on the transport networks opportunities, connecting regional communities these major investments is essential. Infrastructure of Regional NSW are very different to those of and supporting freight movements. NSW is concerned that cost estimates for these metropolitan NSW. programs appear very high. • Regional NSW has extensive and well–developed • The road network is the dominant mode for regional regional road and rail networks connecting • Unlocking the key constraints along the road and passenger travel. Over 90 percent of the 7.5 million population and employment centres across rail networks that limit freight movements are likely journeys made each day are by car1. the state. In recent years, the NSW State and to have some of the highest economic benefits in Commonwealth Governments have undertaken the regions. This includes upgrading understrength • There is limited usage of regional and interstate public major investment to improve the quality and road bridges, providing rail passing loops and transport. Regional train services carry less than capacity of these networks. ensuring roads and rail lines are well-maintained 6,000 passengers a day. Regional bus and coach and effectively managed. services transport around almost three times as • The road network is the backbone of regional many, approximately 15,000 passengers a day2. -

Monitoring Fauna Sensitive Road Design in a Woodland Environment – Is There a Conflict Between Short-Term Compliance and Long-Term Research Values?

MONITORING FAUNA SENSITIVE ROAD DESIGN IN A WOODLAND ENVIRONMENT – IS THERE A CONFLICT BETWEEN SHORT-TERM COMPLIANCE AND LONG-TERM RESEARCH VALUES? AMY EVANS MONITORING FAUNA SENSITIVE ROAD DESIGN IN A WOODLAND ENVIRONMENT My Background MONITORING FAUNA SENSITIVE ROAD DESIGN IN A WOODLAND ENVIRONMENT Location (Source: Google Maps, 2014) MONITORING FAUNA SENSITIVE ROAD DESIGN IN A WOODLAND ENVIRONMENT Fauna Mitigation Examples Glider Crossings Rope Bridges Glider Poles MONITORING FAUNA SENSITIVE ROAD DESIGN IN A WOODLAND ENVIRONMENT Fauna Mitigation Examples Nest Boxes MONITORING FAUNA SENSITIVE ROAD DESIGN IN A WOODLAND ENVIRONMENT Fauna Mitigation Examples Bird Underpasses MONITORING FAUNA SENSITIVE ROAD DESIGN IN A WOODLAND ENVIRONMENT Fauna Mitigation Examples Fauna Friendly Culverts MONITORING FAUNA SENSITIVE ROAD DESIGN IN A WOODLAND ENVIRONMENT Fauna Mitigation Examples Widened Median Plantings Coarse Woody Debris Placement MONITORING FAUNA SENSITIVE ROAD DESIGN IN A WOODLAND ENVIRONMENT Examples to Discuss 1. Nest Box Monitoring Program 2. Squirrel Glider Monitoring Program at Thurgoona 3. Landscaping as a mitigation measure MONITORING FAUNA SENSITIVE ROAD DESIGN IN A WOODLAND ENVIRONMENT Nest Box Monitoring Program • The Duplication of the Hume Highway from Sturt Hwy to Tabletop resulted in removal of 231 hollow bearing trees, containing 580 hollows. • The Ministerial Conditions of Approval (MCoA) for the project outline the proponent’s duties with regard to hollow dependent fauna and nest boxes. The MCoA state: “The Proponent -

BP National Diesel Offer to Find Your Nearest BP Site, Visit Bpsitelocator.Com.Au

BP National Diesel Offer To find your nearest BP site, visit bpsitelocator.com.au Business. The clever way. Contents BP National Diesel Offer Icon Legends National Map > Fuels Facilities NSW State Map > BP Ultimate Diesel 24 Shop Showers Sydney Map > Diesel 24 OPT WiFi VIC State Map > AdBlue Pump Truck Parking Drivers Lounge Melbourne Map > QLD State Map > AdBlue Pack Weighbridge Food Offer Brisbane Map > High Flow Toilets Take Away Food SA State Map > Ultra High Flow Laundry Wild Bean Cafe Adelaide Map > WA State Map > Truck Friendly Perth Map > Rigid NT State Map > B-Double ACT State Map > TAS State Map > Road Train To find your nearest BP site, BPBTOM3983 visit bpsitelocator.com.au BP National Diesel Offer Site List 07/20 [2 National Key TruckBP National Routes Diesel Offer New South Wales − Effective June 2020 • Sydney – Brisbane (Pacific Highway - coast) • Sydney – Brisbane (New England Hwy – inland) • Sydney – Melbourne • Sydney – Adelaide • Sydney – Perth • Sydney – Darwin • Melbourne – Adelaide • Melbourne – Perth • Melbourne – Darwin • Melbourne – Brisbane • Adelaide – Perth • Adelaide – Darwin • Adelaide – Brisbane • Perth – Darwin (Inland to Port Hedland, via Newman, then there is only one road to Darwin) • Perth – Brisbane • Darwin – Brisbane • Hobart – Burnie • Perth – Port Hedland (coast, via Carnarvon & Karratha) Back to Contents > To find your nearest BP site, visit bpsitelocator.com.au NSW BP National Diesel Offer New South Wales − Effective May 2021 BP National Diesel Offer Back to Contents > National Map > Sydney Map > To find your nearest BP site, visit bpsitelocator.com.au NSW BP National Diesel Offer New South Wales − Effective May 2021 BP National Diesel Offer Back to Contents > National Map > NSW State Map > To find your nearest BP site, visit bpsitelocator.com.au NSW BP National Diesel Offer New South Wales − Effective May 2021 Max. -

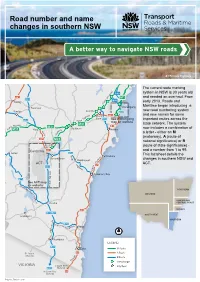

Alpha Numeric Route Number System

Road number and name changes in southern NSW A better way to navigate NSW roads A1 Princes Highway y The current route marking a rw B69 to A41 o system in NSW is 30 years old M M1 B81 e B88 m and needs an overhaul. From Young u H early 2013, we will introduce a Boorowa Wollongong Berrima Harden B65 new road numbering system y A48 a way Moss and new names for some hw gh g i i H Vale B73 See Wollongong H B94 H e u m map on website important routes across the c pi M31 m Highway Oly e A1 state network. The system will m M31 u Goulburn H M31 Yass ay Nowra B w a h include a combination of a r g t i o H n letter - either an M (motorway), A25 H M23 Gundagai l i g A (route of national a h r e w ed a F y significance) orB (route of Canberra A23 state significance) - and a B72 Tumut B52 K i y Ulladulla n a number from 1 to 99. This Queanbeyan g w s h Braidwood ig factsheet details the changes H ACT H ig s A1 B23 h e in southern NSW. wa c y n i r y P a w Batemans Bay h g i H B72 o r See ACT map a n S on website o now M y M o NORTHERN un ta in s WESTERN H ig h w HUNTER AND a y Cooma CENTRAL COAST A1 SYDNEY B72/B23 SOUTH WEST Jindabyne S SOUTHERN n o w y B72 y M a ounta y ins wa Bega w High h g i H o r a n o M Bombala y a LEGEND w B23 h g i Eden M Route H A1 A Route To Orbost (Victoria) s e B Route n c ri P Interchange VICTORIA To Cann River City/Town B23 (Victoria) To Cann River A1 (Victoria) Pub No. -

Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Engineering and Information Faculty of Informatics - Papers (Archive) Sciences 1-1-2007 Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport Philip G. Laird University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Laird, Philip G.: Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport 2007, 1-14. https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/760 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport Abstract This paper shall commence with reference to the draft AusLink Sydney - Brisbane corridor strategy. Section 2 will outline the upgrading of the Pacific Highway, Section 3 will examine the existing Sydney - Brisbane railway whilst Section 4 will outline some 2009 - 2014 corridor upgrade options with particular attention to external costs and energy use as opposed to intercity supply chain costs. The conclusions are given in Section 5. The current population of the coastal regions of the Sydney - Brisbane corridor exceeds 8 million. As shown by Table I, the population is expected to be approaching 11 million by 2031. The draft strategy notes that Brisbane and South East Queensland will become Australia's second largest conurbation by 2026. Keywords land, transport, brisbane, sydney Disciplines Physical Sciences and Mathematics Publication Details Laird, P. G. (2007). Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport. Australasian Transport Research Forum (pp. 1-14). Online www.patrec.org - PATREC/ATRF. This conference paper is available at Research Online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/760 Sydney - Brisbane land transport Sydney - Brisbane Land Transport Philip Laird University of Wollongong, NSW, Australia 1 Introduction This paper shall commence with reference to the draft AusLink Sydney - Brisbane corridor strategy. -

Additional Permit Conditions

ADDITIONAL PERMIT CONDITIONS The following conditions must be complied with in addition to any specific conditions contained elsewhere in the permit document. OD Routes referred to in the permit document are described at the end of the conditions. (a) in the case of a vehicle exceeding 2.5 metres in 1. INTRODUCTION width or 25.0 metres in length– 1.1 In these conditions, unless the contrary intention (i) four bright red, yellow or red and yellow flags; appears– (ii) a rigid OVERSIZE warning sign attached to the front and rear of the vehicle; and (a) “permit vehicle” means the vehicle or combination (b) if the vehicle exceeds 3.0 metres in width, a yellow in respect of which the permit has been issued; warning light; and (b) “operator’ means the person in whose name the (c) if the vehicle exceeds 22.0 metres in length– permit is issued and includes any principal on whose behalf that person has obtained the permit; (i) a rigid OVERSIZE warning sign attached to the rear of the vehicle; (c) “the Regulations” means the Road Safety (Vehicles) Regulations 1999; 2.7 The warning lights and warning signs must meet the (d) words and phrases have the same meaning as in construction standards and specifications set out in the Regulations. Schedule 1 to the Regulations. 1.2 Unless the contrary intention expressly appears in the permit document, this permit does not apply if the permit vehicle is being operated under any other permit or Gazette Notice issued or published under Part 5 of the Regulations. -

Hume Highway Holbrook Bypass

Hume Highway Upgrade Holbrook bypass Environmental assessment 3. Strategic justification This chapter describes the strategic need, justification and objectives for the project. DGRs Where addressed Strategic justification Describe the strategic need, justification and objectives for the Chapter 3. project (including performance indicators), and consistency with the aims and objectives of the relevant National and State planning policies and provisions, such as the National Land Transport Plan (Auslink) and State Infrastructure Strategy — New South Wales 2006-07 to 2015-16. 3.1 Strategic need The Hume Highway is the main road freight corridor between Sydney and Melbourne, carrying over 20 million tonnes of road freight every year. In addition, the corridor is an important part of the NSW State and regional road network. The Hume Highway is 807 kilometres in length from Sydney to Melbourne — 517 kilometres in NSW and 290 kilometres in Victoria. The section of the highway in Victoria is entirely dual carriageway. Within NSW, dual carriageway conditions are over 80 per cent complete. The existing single carriageway sections of the Hume Highway are all located between Sheahan Bridge (Gundagai) and Albury and dual carriageway construction is underway at several locations. Completion of the dual carriageway for the remaining 20 kilometres — comprising the proposed town bypasses of Tarcutta, Holbrook and Woomargama — would provide consistent dual carriageway conditions along the entire Hume Highway from Sydney to Melbourne. 3.1.1 AusLink White Paper and National Land Transport Plan The AusLink White Paper: Building Our National Transport Future (the White Paper) (Federal Government 2004) is the Federal Government’s formal policy statement on land transport.