Quantitative and Qualitative Research: Conflicting Paradigms Or Perfect Partners?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Open University MBA 2015/2016 Foreword by Professor Rebecca Taylor, Dean, OU Business School (OUBS)

The Open University MBA 2015/2016 Foreword by Professor Rebecca Taylor, Dean, OU Business School (OUBS) The global marketplace is more challenging than ever before. Organisations need executives who are agile, resilient and can work across boundaries; who can understand the theory of management and business and apply this in the real world; and who can spot and react to new threats and opportunities. These are the executives who will drive growth and success in the future. At the OU Business School, we offer a cutting-edge, practice-based MBA programme developed by leading business academics. We work alongside businesses and our students to deliver an MBA that builds executive business skills while you continue to operate in the workplace. This ensures that you critically assess and apply new skills as they are learned and it means that we can support you in taking the next step in your career. The OU’s vast experience of developing study programmes, allied with our individual approach to business education, enables the OU Business School to offer a tailored and effective MBA that is uniquely placed to assist you in your journey to becoming a highly effective executive. This allows sponsoring employers to see an immediate return on investment while also helping to retain valued and skilled individuals. 3 Values, vision and mission The OU Business School has over 30 years’ experience in helping businesses and ambitious executives across the globe achieve their true potential through innovative practice-based study programmes. Our values Responsive By listening to students and organisations we have been able to: Inclusive • respond to the needs of individuals, employers and the communities in which they live and work Our ability to offer a wide range of support services to students and a championing of ethical standards means that we are • dedicate resources to support our students’ learning success. -

Course Entry Requirement Statement for 2021 Entry

Course Entry Requirements Statement for 2021 Entry Course Entry Requirement Statement for 2021 Entry Contents Scope and Purpose ........................................................................................ 3 UK QUALIFICATIONS ......................................................................................... 4 GCSEs and equivalent qualifications .................................................................... 4 A’Levels and equivalent qualifications ................................................................. 4 EU AND INTERNATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS .............................................................. 19 Maritime Courses ........................................................................................ 31 ENGLISH LANGUAGE REQUIREMENTS .................................................................... 29 APPENDIX A: EXEMPTIONS AND EXCEPTIONS ......................................................... 29 APPENDIX B: ACCEPTABLE ENGLISH LANGUAGE QUALIFICATIONS FOR STUDENTS REQUIRING A STUDENT ROUTE VISA ................................................................................... 32 APPENDIX C: EUROPEAN SCHOOL LEAVING/MATRICULATION CERTIFICATES EQUIVALENT TO IELTS (ACADEMIC) 6.0 OVERALL ....................................................................... 38 External Relations | Admissions and Enrolment 2 Updated April 2021 Course Entry Requirements Statement for 2021 Entry Scope and Purpose 1. This document is designed for use by Solent University (SU) staff when evaluating applicants for entry -

Conference Programme

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Please refer to session descriptions for further information about the workshops Monday 20th July 2.00pm – 5.00pm Registration and networking Session This is an opportunity register for the conference, meet and network with other delegates and NADP Directors, gather information about the conference and the City of Manchester Delegates arriving on Tuesday 21st July should first register for the conference. The Registration Desk will be open from 8.00am. Tuesday 21st July 9.00am – 9.30am Welcome to the conference Paddy Turner, Chair of NADP Professor Dame Nancy Rothwell, President of University of Manchester 9.30am – 10.15am Keynote Presentation Scott Lissner, AHEAD and Ohio State University 10.15am – 10.45am Refreshment break 10.45am – 11.45am Parallel workshop session 1 Workshop 1 Inclusive HE beyond borders Claire Ozel, Middle East Technical University, Turkey Workshop 2 Emergency preparedness: maintaining equity of access Stephen Russell, Christchurch Polytechnic, New Zealand Workshop 3 Supporting graduate professional students: an overview of an independent disability services programme with an emphasis on mental illness Laura Cutway and Mitchell C Bailin, Georgetown University Law Centre. USA This programme may be subject to change Workshop 4 This workshop will consist of two presentations Disabled PhD students reflections on living and learning in an academic pressure cooker and the need for a sustainable academia Dieuwertje Dyi Juijg, University of Manchester Great expectations? Disabled students post- graduate -

The Ulster-Scots Language in Education in Northern Ireland

The Ulster-Scots language in education in Northern Ireland European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning hosted by ULSTER-SCOTS The Ulster-Scots language in education in Northern Ireland c/o Fryske Akademy Doelestrjitte 8 P.O. Box 54 NL-8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands T 0031 (0) 58 - 234 3027 W www.mercator-research.eu E [email protected] | Regional dossiers series | tca r cum n n i- ual e : Available in this series: This document was published by the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Ladin; the Ladin language in education in Italy (2nd ed.) and Language Learning with financial support from the Fryske Akademy and the Province Latgalian; the Latgalian language in education in Latvia of Fryslân. Lithuanian; the Lithuanian language in education in Poland Maltese; the Maltese language in education in Malta Manx Gaelic; the Manx Gaelic language in education in the Isle of Man Meänkieli and Sweden Finnish; the Finnic languages in education in Sweden © Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Mongolian; The Mongolian language in education in the People’s Republic of China and Language Learning, 2020 Nenets, Khanty and Selkup; The Nenets, Khanty and Selkup language in education in the Yamal Region in Russia ISSN: 1570 – 1239 North-Frisian; the North Frisian language in education in Germany (3rd ed.) Occitan; the Occitan language in education in France (2nd ed.) The contents of this dossier may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, Polish; the Polish language in education in Lithuania provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to the Mercator European Romani and Beash; the Romani and Beash languages in education in Hungary Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning. -

Lancaster University

RCUK PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT WITH RESEARCH: SCHOOL-UNIVERSITY PARTNERSHIPS INITIATIVE (SUPI) FINAL REPORT - LANCASTER UNIVERSITY SUPI PROJECT NAME: INSPIRING THE NEXT GENERATION NAMES OF CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS REPORT: Ann-Marie Houghton, Jane Taylor, Alison Wilkinson, Catherine Baxendale, Stephanie Bryan, Sharon Huttly Glossary of terms: BOX refers to Research in a BOX which come in a variety of forms, e.g. PCR in a Box, Moot in a Box, Design in a Box, Diet in a Box. EPO Enabling, Process and Outcome indicators used as part of the evaluation framework to identify reasons for success and greater understanding of the challenges encountered, (EPO model developed by Helsby and Saunders 1993) EPQ Extended Project Qualification ECR Early Career Researchers who include PhD, Postdoc and Research Associates LUSU Lancaster University Students’ Union PIs Principle Investigators QES Queen Elizabeth School, Teaching School Alliance including 10 schools who have engaged in activities during the lifetime of Lancaster’s SUPI RinB refers to Research in a BOX which come in a variety of forms, e.g. PCR in a Box, Moot in a Box, Design in a Box, Diet in a Box. SLF South Lakes Federation of which QES is a member, an established strategic network SUPI School University Partnership Initiative funded by RCUK SURE School University Research Engagement the RCUK SUPI legacy project which will include EPQ, Research in a BOX, TURN, and the Brilliant Club, activities developed during the SUPI project TURN Teacher University Research Network that will be one of the SURE project activities UKSRO: Lancaster University’s UK Student Recruitment and Outreach team who have responsibility for marketing, recruitment and widening access outreach. -

The BBA in Management

BBA (HONS) INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT A GUIDE TO YEARS 1 & 2 2019/2020 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION & THE BBA IBM TEAM ................................................................... ………………….…..…2 USEFUL CONTACTS ..................................................................................................... …………………….…3 LUSIPBS, ACCOMMODATION .......................................................................................... …………...….…4 THE ACADEMIC YEAR & ATTENDANCE ............................................................... …............................…5 INTERNSHIPS ............................................................................................................ ……………………..….6 PROGRAMME STRUCTURE PART I, YEAR 1………………………………………………………………………………………7 COMPULSORY MODULES YEAR 1 .............................................................................. ……………………..…7 PROGRAMME STRUCTURE PART II, YEAR 2….……………………………………………………………………………….11 COMPULSORY MODULES YEAR 2………………….………………………………………………………………………………12 US LINK OPTIONAL MODULES YEAR 2..………..………………………………………………………………………………14 LANGUAGE MODULES……………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………..16 EU LINK OPTIONAL MODULES YEAR 2……………..…………………………………………………………………….…….17 ACCOUNTING & FINANCE……………………………………………………………………………………..17 ECONOMICS………………………………………………………………………………………………………….17 ENTREPRENEURSHIP, STRATEGY & INNOVATION………………………………………………….20 MARKETING………………………………………………………………………………………………………….20 MANAGEMENT SCIENCE………………………………………………………………………………….……20 ORGANISATION, WORK & TECHNOLOGY………………………………………………………………22 -

Open University Registration Form

Student’s Last Name Student’s Open University Registration Form IMPORTANT: You must obtain signatures from the instructor and department chair on this form in order to add or drop an Open University course. After you have obtained the required signatures, submit the form to the College of Continuing Education in Napa Hall. Please refer to the Open University web page for registration deadlines and withdrawal procedures for each term. PLEASE PRINT CLEARLY ALL INFORMATION BELOW: Sac State ID First Name Year: Fall Spring Legal Name (Last, First, MI) DIRECTORY INFORMATION Street Address Telephone Number Date of Birth (mm/dd/yy) M.I. City, State, Zip Do you currently have a bachelor’s degree? Gender: Male Female Other/Non-Binary Yes No Email Have you ever attended Sac State classes? Yes No Are you an International Student? Yes No If yes, what type of visa do you hold? List Below All Courses You Wish To Register For: * Required Signatures * Office Use Check one Only 1. Add Class # Audit Drop Dept. & Course# Section # Units Print Instructor’s Name Instructor’s Signature Initials Department Chair's Signature 2. Add Class # Audit Drop Dept. & Course# Section # Units Print Instructor’s Name Instructor’s Signature Initials Department Chair's Signature 3. Add Class # Audit Drop Dept. & Course# Section # Units Print Instructor’s Name Instructor’s Signature Initials Department Chair's Signature Office Use Only I understand that this enrollment does not constitute admission to the Date By university. I have read the information and registration procedures and REG CON understand the procedures of withdrawal and fee refund policy. -

This Item Was Submitted to Loughborough's Institutional Repository by the Author and Is Made Available Under the Following

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-nd/2.5/ Paper More to life than Google – a journey for PhD students Ruth Stubbings and Ginny Franklin Loughborough University Abstract Loughborough University Librarians have become concerned that students, both undergraduate and postgraduate, over estimate their information literacy skills. Students therefore lack motivation to attend and interact during information literacy courses. This paper outlines how Loughborough University Library has tried to encourage postgraduate researchers to reflect on their information searching abilities through the use of checklists and online tests. Research postgraduate students then attend appropriate courses relating to their information literacy needs. Keywords Information literacy, Diagnostic tools, CAA, Postgraduate research skills. Setting the scene: PhD information literacy courses at Loughborough University Prior to 2003/2004 Loughborough University ran a PhD training programme for the Social Science and Humanities Faculty. The programme was administered by the Department of Professional Development and included a two hour compulsory workshop, which was delivered by the Library twice a year. The workshops were assessed. The Library also ran three voluntary workshops twice a year for the Faculties of Science and Engineering (Tracing journal articles, Finding research information and Keeping up-to-date), which were relatively well attended. In response to the Roberts’ review “SET for success”(2002), the University made the Professional Development research training programme available to all PhD students. -

Oxford Cambridge Arc Universities Group

OXFORD CAMBRIDGE ARC UNIVERSITIES GROUP We wholeheartedly support the Government’s strategy for investment across the Oxford-Cambridge Arc and recognise its significance as a driver for economic growth in a region of national strategic importance. As the Arc Universities Group, we commit to working together with business and government, and with one another, to foster research, skills and innovation, in order to further unleash potential for growth and prosperity. SIGNED BY: Professor Nick Braisby Bill Rammell Buckinghamshire New University University of Bedfordshire Professor Alistair Fitt Professor Louise Richardson Oxford Brookes University University of Oxford Professor Sir Peter Gregson Sir Anthony Seldon Cranfield University The University of Buckingham Professor Mary Kellett Professor Stephen Toope The Open University University of Cambridge Professor Nick Petford Professor Roderick Watkins University of Northampton Anglia Ruskin University Vice-Chancellors of the ten universities in the Oxford – Cambridge Arc 12 UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE ARC UNIVERSITIES GROUP 2 UNIVERSITY OF UNIVERSITY NORTHAMPTON OF CAMBRIDGE ANGLIA RUSKIN UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF BEDFORDSHIRE CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY THE OPEN UNIVERSITY THE UNIVERSITY OF BUCKINGHAM TEN UNIVERSITIES ONE FUTURE ARC UNIVERSITIES GROUP OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD BUCKINGHAMSHIRE NEW UNIVERSITY GENERATING £5bn £13bn COMBINED TURNOVER FOR THE ECONOMY Leading the way OXFORD UNIVERSITY in global innovation OF CAMBRIDGE CAMBRIDGE Underpinning UK ARC UNIVERSITIES GROUP competitiveness -

Design Education Today Technical Contexts, Programs and Best Practices Edited by D

Design Education Today Technical Contexts, Programs and Best Practices Edited by D. Schaefer (University of Liverpool), G. Coates (Newcastle University) and C. Eckert (The Open University) CALL FOR CHAPTERS Scope Design is a subject of universal importance. Due to its inherent necessity to combine creativity, cognitive and technological competencies as well as business perspectives, design is one of the few subjects not likely to be replaced by computers in the foreseeable future. In addition, it is often referred to as a key driver of innovation and hence a nation’s prosperity. Good design is human-centred, commercially viable, technologically sound and socially responsible. The experience of good design and the ownership of functional, usable and desirable products is valuable to people across their professional and domestic lives. Our society depends on large-scale design projects being delivered successfully. Design has a significant impact on and is impacted by individuals, groups, societies and cultures. It is both a scientific/technical discipline and an art that provides opportunities for people to realise their goals and aspirations. The purpose of this book is to provide an insight into the key technical design disciplines, education programmes, international best practices and delivery modes aimed at preparing the trans-disciplinary design workforce of near tomorrow, grounded in recent advancements in design research. This includes ancillary topics such as design in the context of public policy, standards for professional registration and design programme accreditation. It is meant to serve as a handbook for design practitioners and managers, educators, curriculum designers, programme leaders, and all those interested in pursuing and/or developing a career related to the more technical aspects of design. -

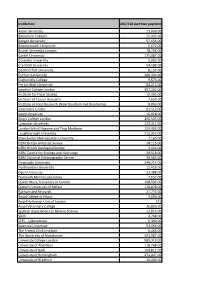

2017-18 Block Grant Awards – Part Two Payments

Institution 2017/18 part two payment Aston University 11,000.00 Babraham Institute 15,095.00 Bangor University 57,656.00 Bournemouth University 5,672.00 Brunel University London 78,766.00 Cardiff University 175,087.00 Coventry University 9,083.00 Cranfield University 54,588.00 De Montfort University 8,137.00 Durham University 200,334.00 Goldsmiths College 9,573.00 Heriot-Watt University 84,213.00 Imperial College London 357,202.00 Institute for Fiscal Studies 10,303.00 Institute of Cancer Research 7,620.00 Institute of Food Research (Now Quadram Inst Bioscience) 8,853.00 John Innes Centre 63,512.00 Keele University 16,918.00 King's College London 296,503.00 Lancaster University 123,311.00 London Sch of Hygiene and Trop Medicine 153,402.00 Loughborough University 212,352.00 Manchester Metropolitan University 7,165.00 NERC British Antarctic Survey 28,115.00 NERC British Geological Survey 3,424.00 NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology 24,518.00 NERC National Oceanography Centre 26,992.00 Newcastle University 248,714.00 Northumbria University 12,456.00 Open University 31,388.00 Plymouth Marine Laboratory 7,657.00 Queen Mary, University of London 198,434.00 Queen's University of Belfast 110,878.00 Rothamsted Research 27,772.00 Royal College of Music 3,690.00 Royal Holloway, Univ of London 215 Royal Veterinary College 26,890.00 Scottish Association For Marine Science 12,814.00 SRUC 4,768.00 STFC - Laboratories 5,390.00 Swansea University 51,494.00 The Francis Crick Institute 6,466.00 The University of Manchester 591,987.00 University College -

Andy Breeze, Ofs John Britton, Cardiff

DISCUSSION AROUND FTE – SECOND PROPOSAL 15 JANUARY 2019, 10:00 CONFERENCE CALL Present: Andy Breeze, OfS John Britton, Cardiff University Chris Carpenter, Loughborough University Christine Couper, The University of Greenwich Suzie Dent, HESA Judith Dutton, Open University Jeanne Farrow, HESA Rachel Fuidge, HESA Debbie Grossman, The University of Greenwich Liz Heal, HEFCW James McLaren, HESA (at the end) Hazel Miles, HESA Daniel Norton, Loughborough University Emma Thomas, Open University Hoa Tu, Open University Ruth Underwood, HESA ACTION POINTS FROM LAST CALL ACTION: OfS / HEFCW to consider if this approach would work for them. Would providers need to submit all their future module data? OUTCOME: Second proposal reached, so this has been considered ACTION: HESA to include a derived field for the last three reference periods of FTE values. OUTCOME: HESA is still considering the options here. ACTION: HESA to communicate FTE proposals to colleagues working with League tables, to make them aware. OUTCOME: this has been done. COMMENTS FROM PROVIDERS AS TO WHETHER OR NOT THIS APPROACH WORKS OfS: took us through the excel spreadsheet they sent around this morning. This shows test data from Greenwich calculated using different methods. OfS will not use the planned FTE as a prediction of the futures, it will only be used retrospectively in case the student drops out. Higher Education Statistics Agency Limited is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England at 95 Promenade, Cheltenham, GL50 1HZ. Page 1 of 4 Registered No. 02766993. Registered Charity No. 1039709. Certified to ISO 27001. The members are Universities UK and GuildHE. Action: OfS to recirculate the spreadsheet with the worked examples with a bit more detail than was currently contained in it.