Orangi Pilot Project, Karachi, Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

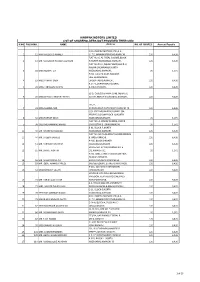

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

Services for the Urban Poor a People-Centred Approach by George Mcrobie

Services for the Urban Poor A People-centred Approach by George McRobie George McRobie was educated in Scotland. At the age Contents of 17 he began to work in the coal mines. He studied as an evening student and earned a degree at London Preface 4 School of Economics in his 20s. In 1956 he became assistant to E.F. Schumacher, then Acknowledgements 4 Economic Adviser to the National Coal Board, and 10 1 Introduction 4 years later helped him form the Intermediate Technol- Problem 4 ogy Group in London. He left the Coal Board to work Method 5 on small industry development in India, and during his Organization of the Report 5 three years there, started the Appropriate Technology Development Association of India. In 1968 he returned 2 General Considerations 5 to London as an executive Director of the Intermediate The Urban Poor and Health 5 Technology Group. On Schumacher’s death in 1977, Different Strategies for Providing Services 6 McRobie became Chairman of the Group and published Appropriate Technologies for Service Provision 7 Small is Possible, a sequel to Schumacher’s Small is Water Supply 7 Beautiful. Sanitation 8 He has worked for many years as a consultant on ap- Household Garbage 10 propriate technology and rural development in Africa, Costs of Service Options 11 Asia and Latin America. He serves on the governing bodies of Intermediate Technology, the India Develop- 3 Recommendations 12 ment Group, the New Economics Foundation and the Community Involvement and the Role of Soil Association, and two non-profit companies promot- Government 12 ing appropriate technologies in Europe and the Third Design of a Community-Based Programme 13 World, Technology Exchange and the Bureau of Knowl- Implementation of a Community- edge and Finance. -

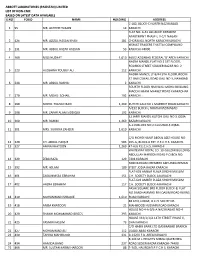

Hinopak Motors Limited List of Shareholders Not Provided Their Cnic S.No Folio No

HINOPAK MOTORS LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS NOT PROVIDED THEIR CNIC S.NO FOLIO NO. NAME Address NO. OF SHARES Amount Payable C/O HINOPAK MOTORS LTD.,D-2, 1 12 MIR MAQSOOD AHMED S.I.T.E.,MANGHOPIR ROAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO. 6, AL-FAZAL SQUARE,BLOCK- 2 13 MR. MANZOOR HUSSAIN QURESHI H,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO.19-O, IQBAL PLAZA,BLOCK-O, NAGAN CHOWRANGI,NORTH 3 18 MISS NUSRAT ZIA NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 20 1,071 H.NO. E-13/40,NEAR RAILWAY LINE,GHARIBABAD, 4 19 MISS FARHAT SABA LIAQUATABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 R.177-1,SHARIFABADFEDERAL 5 24 MISS TABASSUM NISHAT B.AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 52-D, Q-BLOCK,PAHAR GANJ, NEAR LAL 6 28 MISS SHAKILA ANWAR FATIMA KOTTHI,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 171/2, 7 31 MISS SAMINA NAZ AURANGABAD,NAZIMABAD,KARACHI-18. 120 6,426 C/O. SYED MUJAHID HUSSAINP-394, PEOPLES COLONYBLOCK-N, NORTH 8 32 MISS FARHAT ABIDI NAZIMABADKARACHI, 20 1,071 FLAT NO. A-3FARAZ AVENUE, BLOCK- 9 38 SYED MOHAMMAD HAMID 20GULISTAN-E-JOHARKARACHI, 20 1,071 B-91, BLOCK-P,NORTH 10 40 MR. KHURSHID MAJEED NAZIMABAD,KARACHI. 120 6,426 FLAT NO. M-45,AL-AZAM SQUARE,FEDRAL 11 44 MR. SALEEM JAWEED B. AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 A-485, BLOCK-DNORTH 12 51 MR. FARRUKH GHAFFAR NAZIMABADKARACHI. 120 6,426 HOUSE NO. D/401,KORANGI NO. 5 13 55 MR. SHAKIL AKHTAR 1/2,KARACHI-31. 20 1,071 H.NO. 3281, STREET NO.10,NEW FIDA HUSSAIN SHAIKHA 14 56 MR. -

Fathers' Perception of Child Health: a Case Study

Health Transition Review 5, 1995, 191 - 206 Fathers’ perception of child health: a case study in a squatter settlement of Karachi, Pakistan* Albrecht Jahna and Asif Aslamb aUniversity of Heidelberg, Institute of Tropical Medicine and Public Health bUNICEF Pakistan, Karachi, formerly Aga Khan University, Karachi Abstract This study looks at child health from a father’s perspective. While the close relationship between children and mothers has been acknowledged, and brought about the concept of Mother and Child Health (MCH), little attention has been paid to the role of fathering. In Pakistan, where the study was undertaken, a high infant and under-five mortality coincides with a low acceptance of MCH services and a tradition of female seclusion, , which severely limits women’s movements in public. Purdah is often cited as an important cause for the low MCH-coverage, indicating an inappropriate design of established MCH-services with its exclusive focus on mothers, and prompting the questions taken up in this study: what is the role of fathers in child health, how do they define child health needs and how do they participate in child care? The study was undertaken in the squatter settlement Orangi in Karachi where the Aga Khan University is involved in a PHC program. A set of qualitative methods was used including key informant interviews, focus group interviews with fathers, group interviews with women and community health workers with a total of 61 informants, and observation of father-child interaction. Apart from their basic role as breadwinners, most fathers participate directly in child care. As far as working hours allow, fathers spend time with their children by taking them out or playing with them. -

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

Global Urban Poverty: Setting the Agenda

GLOBAL URBAN POVER Comparative Urban Studies Project GLOBAL URBAN POVERTY SETTING THE AGENDA TY : SETTING THE AGENDA CONTRIBUTORS Victor Barbiero, Anne Line Dalsgaard, Diane Davis, Edesio Fernandes, Karen Tranberg Hansen, Arif Hasan, Loren B. Landau, Gordon McGranahan, Diana Mitlin, Richard Stren, Karen Valentin, Vanessa Watson This publication is made possible through support provided by the Urban Programs Team of the Office of Poverty Reduction in the Bureau of Economic Growth, Agriculture and Trade, U.S. Agency for International Development under the terms of the Cooperative Agreement No. GEW-A-00-02-00023-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not nec- essarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the Woodrow Wilson Center. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Comparative Urban Studies Program Edited by ALLISON M. GARLAND, 1300 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. Washington, DC 20004 Tel. (202) 691-4000 Fax (202) 691-4001 MEJGAN MASSOUMI www.wilsoncenter.org and BLAIR A. RUBLE GLOBAL URBAN POVERTY: SETTING THE AGENDA Edited by Allison M. Garland, Mejgan Massoumi and Blair A. Ruble WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by providing a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and col- laboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and international affairs. -

The Early Marriage: Origin of Domestic Violence and Reproductive Health Challenges (With Special Reference to Orangi Town –Karachi)

The Early Marriage: Origin of Domestic Violence and Reproductive Health Challenges (With Special Reference to Orangi Town –Karachi) Nisar Ahmed Nisar* Zubair Latif* Saeeda Khan* Sumera Ishrat** Abstract This traditional practice affecting not only the reproductive health of young girls but it is a major cause of domestic violence as well. This issue has been calling the care of national and international organizations in modern societies, containing Pakistan. Numerous issues which support this belief include poverty, lake of education, the perception of “virginity” of a single girl as key to a family‟s honor, family building (whether joint family or nuclear family), spiritual clarification of being an adult, and short employment opportunities consequence in whole necessity of these girls on their manlike blood relatives. However, the present literature review revealed that there is no comprehensive study on child marriages and its impact on girls‟ reproductive health common in Pakistan. The objectives of the present study were to study the causes of early marriages, domestic violence, and reproductive health problems as well as evaluate socio-economic features on this practice. Orangi Town then the oldest slum settlement of Karachi city was treated as the research universe in the present study while it‟s UC-12 „Mujahidabad‟ and UC-13 „Baloch Goth‟ was the target areas. This research was a qualitative study where the researchers selected the mixed-method strategy for data collection. The snowball sampling and convenience sampling techniques were adopted. A tailor-made Questionnaire was used for data collection. The data was analyzed in tabular form and relevant case studies were also incorporated. -

Public and Private Control and Contestation of Public Space Amid Violent Conflict in Karachi

Public and private control and contestation of public space amid violent conflict in Karachi Noman Ahmed, Donald Brown, Bushra Owais Siddiqui, Dure Shahwar Khalil, Sana Tajuddin and Gordon McGranahan Working Paper Urban Keywords: November 2015 Urban development, violence, public space, conflict, Karachi About the authors Published by IIED, November 2015 Noman Ahmed, Donald Brown, Bushra Owais Siddiqui, Dure Noman Ahmed: Professor and Chairman, Department of Shahwar Khalil, Sana Tajuddin and Gordon McGranahan. 2015. Architecture and Planning at NED University of Engineering Public and private control and contestation of public space amid and Technology in Karachi. Email – [email protected] violent conflict in Karachi. IIED Working Paper. IIED, London. Bushra Owais Siddiqui: Young architect in private practice in http://pubs.iied.org/10752IIED Karachi. Email – [email protected] ISBN 978-1-78431-258-9 Dure Shahwar Khalil: Young architect in private practice in Karachi. Email – [email protected] Printed on recycled paper with vegetable-based inks. Sana Tajuddin: Lecturer and Coordinator of Development Studies Programme at NED University, Karachi. Email – sana_ [email protected] Donald Brown: IIED Consultant. Email – donaldrmbrown@gmail. com Gordon McGranahan: Principal Researcher, Human Settlements Group, IIED. Email – [email protected] Produced by IIED’s Human Settlements Group The Human Settlements Group works to reduce poverty and improve health and housing conditions in the urban centres of Africa, Asia -

Informal Land Controls, a Case of Karachi-Pakistan

Informal Land Controls, A Case of Karachi-Pakistan. This Thesis is Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Saeed Ud Din Ahmed School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University June 2016 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… i | P a g e STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………………………………………..………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed …………………………………………………………….…………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed …………………………………………………….……………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… ii | P a g e iii | P a g e Acknowledgement The fruition of this thesis, theoretically a solitary contribution, is indebted to many individuals and institutions for their kind contributions, guidance and support. NED University of Engineering and Technology, my alma mater and employer, for financing this study. -

Development of Goverment Schools Based on GIS: a Case Study Of

E-ISSN : 2541-5794 P-ISSN : 2503-216X Journal of Geoscience, Engineering, Environment, and Technology Vol 02 No 04 2017 Development of Goverment Schools Based on GIS: A Case Study of Orangi Town, Karachi Sumaira Zafar 1*, Maha Qaisar1, Zainab Sohail1, Arjumand Zaidi2 1-2 Department of Remote Sensing and GISc, Institute of Space Technology (IST)-Karachi, 2 USAID Advance Center for Water Studies, Mehran University of Engineering and Technology-Jamshoro * Corresponding author : [email protected] Tel.:+92-21-34650765 Ext 2296 Received: June 6, 2017. Revised : Sept 18 2016, Accepted: Oct 09, 2017, Published: 1 Dec 2017 DOI : 10.24273/jgeet.2017.2.4.348 Abstract The primary school system in Pakistan needs improvement in order to provide the basic right of education to all. Government schools are not enough to cater the needs of increasing population of the country. The main goal of this study was to present a methodology for the development of government schools based on geographical information system (GIS) through a case study of Orangi Town in Karachi. In this study, first the adequacy of government schools in the study area was evaluated and then the need for additional schools with their suitable locations were identified. Data regarding school locations and students enrollments were collected from Sindh Basic Education Program of a non-profit NGO iMMAP. School building footprints were digitized from 2001 and 2013 Google Earth archived images. Population in 2013 was estimated by projecting 1998 census data downloaded from the website of the Census Bureau of Pakistan. An educated assumption of 20 % of the total population of Orangi Town was used to calculate number of primary school-aged children. -

Urdu Bazaar a Study on the Acceptability of Alternative Energy Sources for a Book Market in Karachi

Urdu Bazaar A study on the acceptability of alternative energy sources for a book market in Karachi Arif Hasan and Mansoor Raza with Hira Ilyas Bawahab Access to Energy series Series Editor Emma Wilson First published by International Institute for Environment and Development (UK) in 2013 Copyright © International Institute for Environment and Development All rights reserved ISBN: 978-1-84369-924-8 For further information please contact: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) 80-86 Gray’s Inn Road, London WC1X 8NH United Kingdom [email protected] www.iied.org/pubs A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Citation: Hasan, A., Mansoor, R., Bawahab, H. I. 2013. Urdu Bazaar: A study on the acceptability of alternative energy sources for a book market in Karachi. International Institute for Environment and Development, London. All photography: Hira Bawahab Design by: SteersMcGillanEves 01225 465546 Printed by: The Russell Press www.russellpress.com Edited by Clare Rogers Disclaimer: This paper represents the view of the authors and not necessarily that of IIED. Executive Summary Urdu Bazaar A study on the acceptability of alternative energy sources for a book market in Karachi Arif Hasan and Mansoor Raza with Hira Ilyas Bawahab Table of Contents Executive summary 4 Chapter 1: Introduction 7 Chapter 2: The Survey Process 11 Chapter 3: Research Findings 13 Chapter 4: Meeting between The Selected Solar Company and the Urdu Bazaar Welfare Association 24 Chapter 5: Follow-up activities 26 Chapter 6: Conclusion 28 Reference Section 29 Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire 30 Appendix 2: Cost comparisons 31 Appendix 3: Newspaper clippings 35 Appendix 4: PowerPoint® presentation of the study 36 Appendix 5: Letter to Secretary of the Power Department 51 1 About the authors Hira Ilyas Bawahab is an architect at the prestigious National College of Arts, Lahore, Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private Pakistan.