Case Studies on the Orangi Pilot Project (Sanitation)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butcher, W. Scott

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project WILLIAM SCOTT BUTCHER Interviewed by: David Reuther Initial interview date: December 23, 2010 Copyright 2015 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Dayton, Ohio, December 12, 1942 Stamp collecting and reading Inspiring high school teacher Cincinnati World Affairs Council BA in Government-Foreign Affairs Oxford, Ohio, Miami University 1960–1964 Participated in student government Modest awareness of Vietnam Beginning of civil rights awareness MA in International Affairs John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies 1964–1966 Entered the Foreign Service May 1965 Took the written exam Cincinnati, September 1963 Took the oral examination Columbus, November 1963 Took leave of absence to finish Johns Hopkins program Entered 73rd A-100 Class June 1966 Rangoon, Burma, Country—Rotational Officer 1967-1969 Burmese language training Traveling to Burma, being introduced to Asian sights and sounds Duties as General Services Officer Duties as Consular Officer Burmese anti-Indian immigration policies Anti-Chinese riots Ambassador Henry Byroade Comment on condition of embassy building Staff recreation Benefits of a small embassy 1 Major Japanese presence Comparing ambassadors Byroade and Hummel Dhaka, Pakistan—Political Officer 1969-1971 Traveling to Consulate General Dhaka Political duties and mission staff Comment on condition of embassy building USG focus was humanitarian and economic development Official and unofficial travels and colleagues November -

Social Entrepreneurship – Creating Value for the Society Dr

Prabadevi M. N., International Journal of Advance Research, Ideas and Innovations in Technology. ISSN: 2454-132X Impact factor: 4.295 (Volume3, Issue2) Available online at www.ijariit.com Social Entrepreneurship – Creating Value for the Society Dr. M. N. Prabadevi SRM University [email protected] Abstract: Social entrepreneurship is the use of the techniques by start-up companies and other entrepreneurs to develop, fund and implement solutions to social, cultural, or environmental issues. This concept may be applied to a variety of organizations with different sizes, aims, and beliefs. Social Entrepreneurship is the attempt to draw upon business techniques to find solutions to social problems. Conventional entrepreneurs typically measure performance in profit and return, but social entrepreneurs also take into account a positive return to society. Social entrepreneurship typically attempts to further broad social, cultural, and environmental goals often associated with the voluntary sector. At times, profit also may be a consideration for certain companies or other social enterprises. Keywords: Social Entrepreneurship, Values, Society. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Defining social entrepreneurship Social entrepreneurship refers to the practice of combining innovation, resourcefulness, and opportunity to address critical social and environmental challenges. Social entrepreneurs focus on transforming systems and practices that are the root causes of poverty, marginalization, environmental deterioration and accompanying the loss of human dignity. In so doing, they may set up for-profit or not-for-profit organizations, and in either case, their primary objective is to create sustainable systems change. The key concepts of social entrepreneurship are innovation, market orientation and systems change. 1.2 Who are Social Entrepreneurs? A social entrepreneur is a society’s change agent: pioneer of innovations that benefit humanity Social entrepreneurs are drivers of change. -

Cyclone Contigency Plan for Karachi City 2008

Cyclone Contingency Plan for Karachi City 2008 National Disaster Management Authority Government of Pakistan July 2008 ii Contents Acronyms………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..iii Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………....iv General…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Aim………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 Scope…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 Tropical Cyclone………………………………………………………………………………………..……………….2 Case Studies Major Cyclones………………………..……………………………………… ……………………….3 Historical Perspective – Cyclone Occurrences in Pakistan…...……………………………………….................6 General Information - Karachi ….………………………………………………………………………………….…7 Existing Disaster Response Structure – Karachi………………………. ……………………….…………….……8 Scenarios for Tropical Cyclone Impact in Karachi City ……………………………………………………….…..11 Scenario 1 ……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..11 Scenario 2. ……………………………………………………………………………………………….….13 Response Scenario -1…………………… ……………………………………………………………………….…..14 Planning Assumptions……………………………………………………………………………………....14 Outline Plan……………………………………………………………………………………………….….15 Pre-response Phase…………………………………………………………………………………….… 16 Mid Term Measures……………………………………………………………………..………..16 Long Term Measures…………………...…………………….…………………………..……...20 Response Phase………… ………………………..………………………………………………..………21 Provision of Early Warning……………………. ......……………………………………..……21 Execution……………………….………………………………..………………..……………....22 Health Response……………….. ……………………………………………..………………..24 Coordination Aspects…………………………………………….………………………...………………25 -

Drivers of Climate Change Vulnerability at Different Scales in Karachi

Drivers of climate change vulnerability at different scales in Karachi Arif Hasan, Arif Pervaiz and Mansoor Raza Working Paper Urban; Climate change Keywords: January 2017 Karachi, Urban, Climate, Adaptation, Vulnerability About the authors Acknowledgements Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, A number of people have contributed to this report. Arif Pervaiz dealing with urban planning and development issues in general played a major role in drafting it and carried out much of the and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved research work. Mansoor Raza was responsible for putting with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1981. He is also a together the profiles of the four settlements and for carrying founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in out the interviews and discussions with the local communities. Karachi and has been its chair since its inception in 1989. He was assisted by two young architects, Yohib Ahmed and He has written widely on housing and urban issues in Asia, Nimra Niazi, who mapped and photographed the settlements. including several books published by Oxford University Press Sohail Javaid organised and tabulated the community surveys, and several papers published in Environment and Urbanization. which were carried out by Nur-ulAmin, Nawab Ali, Tarranum He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign Naz and Fahimida Naz. Masood Alam, Director of KMC, Prof. community-based organisations, national and international Noman Ahmed at NED University and Roland D’Sauza of the NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies; NGO Shehri willingly shared their views and insights about e-mail: [email protected]. -

Mike Davis, Planet of Slums

- Planet of Slums • MIKE DAVIS VERSO London • New York formy dar/in) Raisin First published by Verso 2006 © Mike Davis 2006 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 357910 864 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F OEG USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014 -4606 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN 1-84467-022-8 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Garamond by Andrea Stimpson Printed in the USA Slum, semi-slum, and superslum ... to this has come the evolution of cities. Patrick Geddes1 1 Quoted in Lev.isMumford, The City inHistory: Its Onj,ins,Its Transf ormations, and Its Prospects, New Yo rk 1961, p. 464. Contents 1. The Urban Climacteric 1 2. The Prevalence of Slums 20 3. The Treason of the State 50 4. Illusions of Self-Help 70 5. Haussmann in the Tropics 95 6. Slum Ecology 121 .7. SAPing the Third World 151 ·8. A Surplus Humanity? 174 Epilogue: Down Vietnam Street 199 Acknowledgments 207 Index 209 1 The U rhan Climacteric We live in the age of the city. The city is everything to us - it consumes us, and for that reason we glorify it. Onookome Okomel Sometime in the next year or two, a woman will give birth in the Lagos slum of Ajegunle, a young man will flee his viJlage in west Java for the bright lights of Jakarta, or a farmer will move his impoverished family into one of Lima's innumerable pueblosjovenes . -

TCS Office Falak Naz Shop # G.2 Ground Floor Flaknaz Plaza Sh-E - Faisal

S No Cities TCS Offices Address Contact 1 Karachi TCS Office Falak Naz Shop # G.2 Ground Floor Flaknaz Plaza Sh-e - Faisal. 0316-9992201 2 Karachi TCS Office Main Head 101-104 CAA Club Road Near Hajj Tarminal - 3 0316-9992202 3 Karachi TCS Office Malir Cantt Shop#180 S-13 Cantt Bazar, Malir Cantonement, Karachi 0316-9992204 4 Karachi TCS Office Malir Court Shop # G-14 Al Raza Sq. New Malir City Near Malir Court 0316-9992207 Shop # 3Haq Baho shopping Center Gulshan e Hadeed Ph.1 Gulshan e 5 Karachi TCS Office Gulshan-E-Hadeed 0316-9992213 Hadeed 6 Karachi TCS Office Korangi No. 4 Shop # 10, Abbasi Fair Trade Centre, Korangi # 4 Opp. KMC Zoo 0316-9992215 7 Karachi TCS Office GULSHAN Chowrangi Shop A 1/30, block No 5. Haider plaza gulshan-e-Iqbal Karachi 0316-9992230 8 Karachi TCS Office GULISTAN-E-JOHAR Shop # Saima Classic Rashid Minas Road Near Johar More 0316-9992231 9 Karachi TCS Office HYDRI Shop # B-13, Al Bohran Circle, Block-B, North Nazimabad. 0316-9992232 10 Karachi TCS Office GULSHAN-E-IQBAL Shop # 06, Plot # B-74 Shelzon Center BI.15 Opp. Usmania Restrent 0316-9992234 11 Karachi TCS Office ORANGI TOWN Banaras Town, Sector 8, Orangi Town Karachi Opp. Banaras Town Masjid 0316-9992236 12 Karachi TCS Office S.I.T.E Shop # 5, SITE Shopping Centre, Manghopir Rd. Opp. MCB SITE Br. 0316-9992237 13 Karachi TCS Office NIPA CHOWRANGI Shop # A -8 KDA Overseas apartment 0316-9992241 S 5 Noman Arcade Bl. 14 Gulshan-e-Iqbal Near Mashriq Centre Sir 14 Karachi TCS Office Mashriq Center 0316-9992250 suleman shah Rd. -

Plan for Irrc in G-15 (Islamabad) Ahkmt-E-Guard Initiative

INTEGRATED RESOURCE RECOVERY CENTRE G/15 ISLAMABAD Recycining center Dhaka Bangladesh Presented By Dr. Akhtar Hameed Khan Memorial Trust PLAN FOR IRRC IN G-15 (ISLAMABAD) AHKMT-E-GUARD INITIATIVE JKCHS Plan for IRRC Private Initiative 1.5 Kanal land by JKCHS Total 4600 plots 3-5 ton capacity IRRC 2200 HH are residing now UN-Habitat and UNESCAP Secondary collection system provided financial support was not available and waste concern and CCD provided technical support for AHKMT the IRRC Primary collection service is providing to almost 1500 hh through mutual agreement Primary collection will be extended gradually within 5 years PARTNERSHIP ARRANGEMENTS SITUATION IN ISLAMABAD As per survey in 2014 total population is 1.67 million and waste amount was 800 tons p/day Landfill site is still required Secondary collection and waste transportation requires huge funds Recyclables and organic material is not being utilized Mostly Housing societies of Zone II and Zone V have not proper waste collection and disposal system Present Situation Mixed Waste Waste Bins Demountable Transfer Containers Stations Landfill PROBLEMS Water Pollution Spread of Disease Vectors Green House Gas Emission Odor Pollution More Land Required for Landfill What is Integrated Resource Recovery Center (IRRC)? IRRC is a facility where significant portion (80-90%) of waste can be composted/recycled and processed in a cost effective way near the source of generation in a decentralized manner. IRRC is based on 3 R Principle. Capacity of IRRC varies from 2 to -

Services for the Urban Poor a People-Centred Approach by George Mcrobie

Services for the Urban Poor A People-centred Approach by George McRobie George McRobie was educated in Scotland. At the age Contents of 17 he began to work in the coal mines. He studied as an evening student and earned a degree at London Preface 4 School of Economics in his 20s. In 1956 he became assistant to E.F. Schumacher, then Acknowledgements 4 Economic Adviser to the National Coal Board, and 10 1 Introduction 4 years later helped him form the Intermediate Technol- Problem 4 ogy Group in London. He left the Coal Board to work Method 5 on small industry development in India, and during his Organization of the Report 5 three years there, started the Appropriate Technology Development Association of India. In 1968 he returned 2 General Considerations 5 to London as an executive Director of the Intermediate The Urban Poor and Health 5 Technology Group. On Schumacher’s death in 1977, Different Strategies for Providing Services 6 McRobie became Chairman of the Group and published Appropriate Technologies for Service Provision 7 Small is Possible, a sequel to Schumacher’s Small is Water Supply 7 Beautiful. Sanitation 8 He has worked for many years as a consultant on ap- Household Garbage 10 propriate technology and rural development in Africa, Costs of Service Options 11 Asia and Latin America. He serves on the governing bodies of Intermediate Technology, the India Develop- 3 Recommendations 12 ment Group, the New Economics Foundation and the Community Involvement and the Role of Soil Association, and two non-profit companies promot- Government 12 ing appropriate technologies in Europe and the Third Design of a Community-Based Programme 13 World, Technology Exchange and the Bureau of Knowl- Implementation of a Community- edge and Finance. -

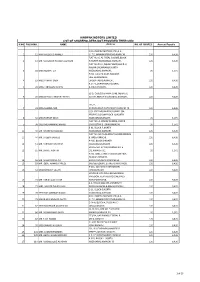

Hinopak Motors Limited List of Shareholders Not Provided Their Cnic S.No Folio No

HINOPAK MOTORS LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS NOT PROVIDED THEIR CNIC S.NO FOLIO NO. NAME Address NO. OF SHARES Amount Payable C/O HINOPAK MOTORS LTD.,D-2, 1 12 MIR MAQSOOD AHMED S.I.T.E.,MANGHOPIR ROAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO. 6, AL-FAZAL SQUARE,BLOCK- 2 13 MR. MANZOOR HUSSAIN QURESHI H,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO.19-O, IQBAL PLAZA,BLOCK-O, NAGAN CHOWRANGI,NORTH 3 18 MISS NUSRAT ZIA NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 20 1,071 H.NO. E-13/40,NEAR RAILWAY LINE,GHARIBABAD, 4 19 MISS FARHAT SABA LIAQUATABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 R.177-1,SHARIFABADFEDERAL 5 24 MISS TABASSUM NISHAT B.AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 52-D, Q-BLOCK,PAHAR GANJ, NEAR LAL 6 28 MISS SHAKILA ANWAR FATIMA KOTTHI,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 171/2, 7 31 MISS SAMINA NAZ AURANGABAD,NAZIMABAD,KARACHI-18. 120 6,426 C/O. SYED MUJAHID HUSSAINP-394, PEOPLES COLONYBLOCK-N, NORTH 8 32 MISS FARHAT ABIDI NAZIMABADKARACHI, 20 1,071 FLAT NO. A-3FARAZ AVENUE, BLOCK- 9 38 SYED MOHAMMAD HAMID 20GULISTAN-E-JOHARKARACHI, 20 1,071 B-91, BLOCK-P,NORTH 10 40 MR. KHURSHID MAJEED NAZIMABAD,KARACHI. 120 6,426 FLAT NO. M-45,AL-AZAM SQUARE,FEDRAL 11 44 MR. SALEEM JAWEED B. AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 A-485, BLOCK-DNORTH 12 51 MR. FARRUKH GHAFFAR NAZIMABADKARACHI. 120 6,426 HOUSE NO. D/401,KORANGI NO. 5 13 55 MR. SHAKIL AKHTAR 1/2,KARACHI-31. 20 1,071 H.NO. 3281, STREET NO.10,NEW FIDA HUSSAIN SHAIKHA 14 56 MR. -

Preparatory Survey Report on the Project for Construction and Rehabilitation of National Highway N-5 in Karachi City in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan

The Islamic Republic of Pakistan Karachi Metropolitan Corporation PREPARATORY SURVEY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION AND REHABILITATION OF NATIONAL HIGHWAY N-5 IN KARACHI CITY IN THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN JANUARY 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY INGÉROSEC CORPORATION EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. EI JR 17-0 PREFACE Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) decided to conduct the preparatory survey and entrust the survey to the consortium of INGÉROSEC Corporation and Eight-Japan Engineering Consultants Inc. The survey team held a series of discussions with the officials concerned of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, and conducted field investigations. As a result of further studies in Japan and the explanation of survey result in Pakistan, the present report was finalized. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of the project and to the enhancement of friendly relations between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste for their close cooperation extended to the survey team. January, 2017 Akira Nakamura Director General, Infrastructure and Peacebuilding Department Japan International Cooperation Agency SUMMARY SUMMARY (1) Outline of the Country The Islamic Republic of Pakistan (hereinafter referred to as Pakistan) is a large country in the South Asia having land of 796 thousand km2 that is almost double of Japan and 177 million populations that is 6th in the world. In 2050, the population in Pakistan is expected to exceed Brazil and Indonesia and to be 335 million which is 4th in the world. -

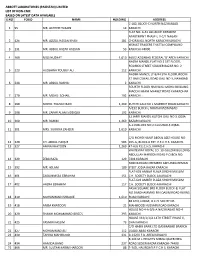

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

New Oxford Social Studies for Paksitan

NEW OXFORD SOCIAL STUDIES TEACHING GUIDE FOR PAKISTAN 3 FOURTH EDITION 5 Introduction The New Oxford Social Studies for Pakistan Fourth Edition has been revised and updated both in terms of text, illustrations, and sequence of chapters, as well as alignment to the National Curriculum of Pakistan 2006. The lessons have been grouped thematically under unit headings. The teaching guides have been redesigned to assist teachers to plan their lessons as per their class needs. Key Learning: at the beginning of each lesson provides an outline of what would be covered during the course of the lesson. Background information: is for teachers to gain knowledge about the topics in each lesson. Lesson plans provide a step-by-step guidance with clearly defined outcomes. Duration of each lesson plan is 40 minutes; however, this is flexible and teachers are encouraged to modify the duration as per their requirements. If required, teachers can utilise two periods for a single lesson plan. Outcomes identify what the students will know and be able to do by the end of the lesson. Resources are materials required in the lesson. Teachers are encouraged to arrange the required materials beforehand. In case students are to bring materials from their homes, they should be informed well ahead of time. Introduction of the lesson plan, sets forth the purpose of the lesson. In case of a new lesson, the teacher would give a brief background of the topic; while for subsequent lessons, the teacher would summarise or ask students to recap what they learnt in the previous lesson. The idea is to create a sense of anticipation in the students of what they are going to learn.