A Step on the Pathway to Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

220 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

220 bus time schedule & line map 220 DCU Helix - Parslickstown Ave View In Website Mode The 220 bus line (DCU Helix - Parslickstown Ave) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Dcu Helix, Stop 7571 →Parslickstown Ave, Stop 1827: 7:34 AM - 9:50 PM (2) Lady's Well Road, Stop 1828 →Dcu Helix, Stop 7571: 6:15 AM - 7:50 PM (3) Lady's Well Road, Stop 1828 →Shangan Road, Stop 4686: 9:10 PM - 10:10 PM (4) Shangan Road, Stop 4686 →Parslickstown Ave, Stop 1827: 6:40 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 220 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 220 bus arriving. Direction: Dcu Helix, Stop 7571 →Parslickstown 220 bus Time Schedule Ave, Stop 1827 Dcu Helix, Stop 7571 →Parslickstown Ave, Stop 1827 89 stops Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:50 AM - 9:50 PM Monday 7:34 AM - 9:50 PM Dcu Helix, Stop 7571 58 Albert College Park, Dublin Tuesday 7:34 AM - 9:50 PM Dcu Collins Avenue, Stop 1644 Wednesday 7:34 AM - 9:50 PM Thursday 7:34 AM - 9:50 PM Albert College Pk 2a Albert College Park, Dublin Friday 7:34 AM - 9:50 PM Ballymun Library Saturday 7:20 AM - 9:50 PM Gateway Avenue Virgin Mary Church, Stop 124 Shangan Road, Dublin 220 bus Info Direction: Dcu Helix, Stop 7571 →Parslickstown Ave, Shangan Road, Stop 4686 Stop 1827 Stops: 89 Virgin Mary Church, Stop 4687 Trip Duration: 96 min Shangan Road, Dublin Line Summary: Dcu Helix, Stop 7571, Dcu Collins Avenue, Stop 1644, Albert College Pk, Ballymun Balbutcher Lane Library, Gateway Avenue, Virgin Mary Church, Stop 124, Shangan Road, Stop 4686, Virgin Mary -

Robert Moss: Green Parks

•A Welcoming Place •Healthy Safe and Secure •Well Maintained and Clean Criteria •Environmental Management •Management of Biodiversity, Landscape and Heritage •Community Involvement •Marketing and Communication •Management •Parks •Gardens •Nature Reserves •Seafront gardens •Cemeteries and Crematoria •Country Parks •Woodland •University Campus •Canals The Assessment Desk assessment 30% Field assessment 70% Pass mark 66% Benefits Independent Benchmarking Technical/Professional Advice Recognition/morale boost for staff and community Promotion of the green space, service and authority Profile within the managing organisation Protect Budget/attract additional resources 2015 2016 Dublin City Council Blessington Street Park Longford County Council The Mall Dublin City Council Bushy Park Dublin City Council Markievicz Park Louth County Council Blackrock Community Park Dublin City Council Poppintree Park Dublin City Council St Anne's Park Mayo County Council Turlough Park Offaly County Council Lloyd Town Park Tullamore Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council Cabinteely Park Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County OPW Saint Stephen's Green Council People’s Park OPW Grangegorman Military Cemetery National War Memorial Garden - Fingal County Council Ardgillan Demesne OPW Islandbridge Fingal County Council Malahide Demesne OPW Derrynane Historic Park Fingal County Council Millennium Park Fingal County Council St. Catherine’s Park West Meath County Council Mullingar Town Park Laois County Council Páirc an Phobail Park Wexford County Council Gorey Town Park and Showgrounds Pollinator Project Award 2017 Poppintree Park – Dublin City Council Bushy Park – Dublin City Council Lloyd Town Park Tullamore – Offaly County Council Urban Improvement from Parks: •High quality open space •Changing recreational trends •Increase in birth rate •Health and well being •Commercial benefits •Educational benefits •Supporting biodiversity •Flood mitigation 2017 Media Coverage !!!!!!!!!. -

Greater Dublin Strategic Drainage Study Final Strategy Report ______

Greater Dublin Strategic Drainage Study Final Strategy Report __________________________________________________________________________________________ Greater Dublin Strategic Drainage Study Final Strategy Report Document Title Final Strategy Report Volume 1 – Main Report Volume 2 – Appendices Document Ref (s): GDSDS/NE02057/035C Date Edition/Rev Status Originator Checked Approved 28/05/04 A Draft N Fleming J Grant M Hand M Edger C O’Keeffe 06/08/2004 B Draft N Fleming J Grant M Hand M Edger C O’Keeffe 27/04/2005 C Final N Fleming J Grant M Hand M Edger C O’Keeffe Contracting Authority (CA) Personnel Council Area Council Name Operations Manager Office Location Project Engineer Name Telephone No. Operations Manager Name Telephone No. This report has been prepared for the Contracting Authority in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment for the Greater Dublin Strategic Drainage Study dated 23rd May 2001. The McCarthy Hyder MCOS Joint Venture cannot accept any responsibility for any use of or reliance on the contents of this report by any third party. _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ GDSDS/NEO2057/035C April 2005 Greater Dublin Strategic Drainage Study Final Strategy Report __________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................................6 1.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................6 -

Here Family, Community and the Economy Can Prosper Together

To the Lord Mayor and Report No. 161/2010 Members of Dublin City Council Report of the Dublin City Manager Annual Report and Accounts 2009 In accordance with Section 221 of the Local Government Act 2001, attached is a Draft of the Annual Report and Accounts 2009. John Tierney Dublin City Manager DUBLIN CITY COUNCIL DRAFT ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2009 Contents: Lord Mayor’s Welcome To be included in Final Edition City Manager’s Welcome To be included in Final Edition Members of Dublin City Council 2009 To be included in Final Edition Senior Management Co-ordination Group To be included in Final Edition Sections: Driving Dublin’s Success Economic Development Social Cohesion Culture, Recreation and Amenity Urban Form Ease of Movement Environmental Sustainability Organisational Matters Appendices: 1. Members of Strategic Policy Committees at December 2009 2. Activities of Strategic Policy Committees 3. Members of Dublin City Development Board 2009 4. Dublin City Council National Services Indicators for 2009 5. Dublin City Council Development Contribution Scheme 6. Conferences and Seminars 2009 7. Recruitment Statistics 8. Publications published in 2009 9. Expenses and Payments 10. Dublin Joint Policing Committee Annual Financial Statements Introduction Statement of Accounting Policies 2009 Annual Financial Statements and General Driving Dublin’s Success Dublin in 2009 Dublin is Ireland’s capital city and is Ireland’s only globally competitive city. 2009 saw a number of dramatic changes at local, national and international levels. Dublin City Council must respond to the challenges presented and continue to serve the people of Dublin and deliver the major work programmes necessary for the smooth running and the future development of the city. -

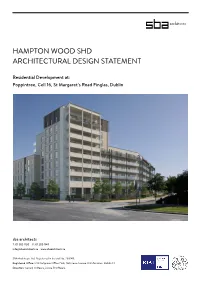

Hampton Wood Shd Architectural Design Statement

HAMPTON WOOD SHD ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN STATEMENT Residential Development at: Poppintree, Cell 16, St Margaret’s Road Finglas, Dublin sba architects T: 01 205 1130 F: 01 205 1149 [email protected] www.sbaarchitects.ie SBA Architects Ltd. Registered in Ireland No. 238149. Registered Office: D13 Nutgrove Office Park, Nutgrove Avenue, Rathfarnham, Dublin 14 Directors: Gerard O’Meara, Janice B O’Meara Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 4 1.2 PLANNING HISTORY & PERMITTED DEVELOPMENT ................................................... 4 2 Area ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 CHARACTER OF SURROUNDING AREA - HOUSING ..................................................... 6 2.2 CHARACTER OF SURROUNDING AREA - APARTMENT BUILDINGS .............................. 7 2.3 CHARACTER OF SURROUNDING AREA – LANDMARK BUILDINGS ............................. 10 3 Site .................................................................................................................................... 11 3.1 PIVOTAL SITE ............................................................................................................. 11 3.2 HAMPTON WOOD DRIVE – PUBLIC THOROUGHFARE AND PUBLIC FACILITIES ........ 13 3.3 TRANSPORT -

Electoral Roll

Number 52A 1 Supplement Published by Authority FRIDAY, 29th JUNE, 2007 This publication is registered for transmission by Inland Post as a newspaper. The postage rate to places within Ireland (32 counties), places in Britain and other places the printed paper rate by weight applies. SEANAD ELECTORAL (PANEL MEMBERS) ACTS 1947 AND 1954 ELECTORAL ROLL The Electoral Roll prepared by the Seanad Returning Officer under section 45 of the Seanad Electoral (Panel Members) Act 1947, as amended by the Seanad Electoral (Panel Members) Act 1954, of persons entitled under section 44 of the Act of 1947 to vote at the election of panel members at the Seanad General Election consequent on the dissolution of Da´il E´ ireann by the Proclamation of the President of the 29th day of April, 2007. Under the heading ‘‘Description’’ the Letter D denotes ‘‘a member of Da´il E´ ireann’’. ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, S ,, ‘‘a member of Seanad E´ ireann’’. ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,, L ,, ‘‘a member of the council of a county or city’’. Uimh. Ainm Tuairisc Seoladh No. Name Description Address 1. Abbey, Michael ...................... L. 32 Green Road, Carlow. 2. Adams, Margaret ................... L. King’s Hill, Westport, Co. Mayo. 3. Ahearne, Liam ....................... L. Ballindoney, Grange, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary. 4. Ahern, Bertie.......................... D. ‘‘St. Luke’s’’, 161 Lower Drumcondra Road, Dublin 9. 5. Ahern, Dermot....................... D. The Crescent, Blackrock, Dundalk, Co. Louth. 6. Ahern, Maurice ...................... L. Carrigogna, Midleton, Co. Cork. 7. Ahern, Maurice ..................... L. Members Room, City Hall, Dublin 2. 8. Ahern, Michael....................... L. 3 Kenley Crescent, Westgate Road, Bishopstown, Cork. 9. Ahern, Michael....................... D. ‘‘Libermann’’, Barryscourt, Carrigtwohill, Co. Cork. -

Directory of Services and Programmes

Community Healthcare Organisation Dublin North City and County Directory of Services and Programmes for Adults with Asthma, COPD, Diabetes, Heart Conditions and Stroke Connecting people living with long term health conditions to services and services to each other. Asthma & COPD Diabetes Heart Conditions Stroke Lifestyle Supports This Directory is a work in progress, and will be updated and recirculated periodically. The most up to date version can be found at: www.hse.ie/selfmanagementsupport. Please contact the Self Management Support Coordinator if you would like to make any suggestion on how it can better meet your needs. Information current as of publication date: 11/06/2019 Prepared by: Therese Clarke HSE Self-Management Support Co-ordinator for Chronic Disease Community Healthcare Organisation Dublin North City and County Email: [email protected] Foreword We are very pleased to issue this first edition of the Dublin North City diabetes education. These essential programmes improve the skills and County Community Healthcare Organisation directory of services and confidence of people with long term health conditions and keep and programmes for adults with Asthma, COPD, Diabetes, Heart them healthier. It also supports health care professionals to implement Conditions and Stroke. This directory aims to assist healthcare and Making Every Contact Count our new health behaviour change community professionals to support adults who are living with a long programme. This will support people to make healthy lifestyle choices term health condition or caring for someone with one. It aims to connect that help prevent chronic diseases. The inclusion of mental wellbeing people with long term health conditions to services and services to supports, social and community supports and peer support groups each other. -

Paddy Flood Ph 087 9697456 Emai

First Ireland Senior Saturday Divisional Secretary: Paddy Flood Ph 087 9697456 emai: [email protected] Ballyogan Celtic Ray Downer 085 7699086 Dressing Rooms 0 0 2.00pm Black 10 Ridge Hill Chris 086 1043386 Ballyogan Ave Showers Orange/Blue Ballybrack 0 0 Co. Dublin 0 [email protected] Balscadden FC Willie Burke 086 3817781 Ringcommon Dressing Rooms Private 0 2.30pm Blue 5 Moylaragh Walk Darren 085 7066221 Sports Centre Showers Amber/Black Balbriggan 0 Facilities for Ref Co. Dublin 0 [email protected] Butterkrust FC Kieran Bree 087 4122173 0 D.C.C. 0 2.30pm Blue 62 Clancy Road 0 Poppintree Pk 0 Red Finglas East 0 0 Dublin 11 0 [email protected] Columbas Rovers Michael McLoughlin 086 3680073 Dressing Rooms Private 0 2.00pm Blue 35 Castlefarm Alan 086 8668880 A.U.L. Showers Red/White Swords 0 Facilities for Ref Co Dublin 0 [email protected] East Wall/Bessborough Larry Connolly 086 2592902 Dressing Rooms Private 0 2.30pm Red/White 58 Church Rd 0 A.U.L. Showers All Black East Wall 0 Facilities for Ref Dublin 3 0 [email protected] Hardwicke FC Anthony Perry 085 2108372 Dressing Rooms Private EWR 2.30pm White/Blue 141 Hardwick St Kevin 087 3150537 Richmond Rd Showers All White Dublin 1 0 Facilities for Ref 0 0 [email protected] Kilmore Celtic Sam Morris 086 1749496 Chanel Leisure Dressing Rooms Private 0 2.00pm Green White 29 Kilbarron Ave Wayne 085 7402428 Centre Showers Green Kilmore West 0 Facilities for Ref Dublin 5 0 [email protected] Railway Union Nicholas Murphy 086 8661342 Park Ave, Dressing Rooms Railway Union 0 2.30pm Yellow/Green 20 Killiney Gate David 01 2691783 Sandymount Showers Wine Church Rd 0 Facilities for Ref Killiney Co Dublin [email protected] Sandyhill/Shangan FC Alan Judge 085 1465820 Dressing Rooms Private 0 2.00pm Navy 5 Scribblestown Pk 0 Coultry Pk Showers Yellow/Blue Finglas 0 Facilities for Ref Dublin 11 0 [email protected] Toplion 1 Saturday Divisional Secretary: Paddy Flood Ph 087 9697456 emai: [email protected] Baldoyle United Gerry Reddy 01 8453361 Baldoyle Dressing Rooms D.C.C. -

Dott in Dublin

DOTT IN DUBLIN Introducing shared e-scooters in Dublin: Opportunities and constraints 31/03/2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 This Study 1 Dott 1 Momentum Transport Consultancy 2 Structure 2 Context 4 Existing Accessibility 4 Demographics 5 Dublin’s Sustainability and Transport Aspirations 9 Micromobility in Dublin 11 Summary 11 E-Scooters in Dublin 12 E-Scooter Impact on Accessibility 12 Opportunities 12 Constraints and Mitigation 14 Characteristics of E-Scooter Trips in Dublin 15 E-Scooter Parking 17 Overview 17 Types of Parking 17 Establishing a Parking Network 19 Trip Types 24 Parking Network Density 26 Alignment with Policy 30 Introduction 30 Stakeholder Engagement 30 Integration with Public Realm and Existing Infrastructure 31 Transport Aspirations 33 Climate Change Policies 34 Conclusion 36 Recommendations 36 Figures Figure 1: Study Area 3 Figure 2: Public transport accessibility and population density in Dublin 6 Figure 3: Workplace density in Dublin 7 Figure 4: Proposed dockless parking areas (conceptual designs) 19 Figure 5: Site Suitability Analysis – Inner Dublin Area 21 Figure 6: Site Suitability Analysis – Outer Dublin Area 23 Figure 7: Potential E-Scooter Trips in Dublin 25 Figure 8: Inner Dublin Area E-Scooter Catchments 28 Figure 9: Outer Dublin Area E-Scooter Catchments 29 INTRODUCTION This Study Momentum Transport Consultancy have undertaken this study commissioned by Dott to understand the opportunities and constraints of shared e-scooters in Dublin city. Whilst the planned introduction of e-scooters has prompted discussions on safety issues, it is also widely recognised that e-scooter sharing schemes have the potential to integrate with existing public transport networks, enhance accessibility and encourage a shift away from private car use, thus reducing carbon emissions. -

Register No Address of Property Folio Reference Ownership Owner

Register No Address of Property Folio Reference Ownership Owner address Market Value Date of Valuation Date entered on Register VS-0002 1-15 Brookfield Road Unregistered EWR Investments Limited No. 1 Terenure Place, Terenure, Dublin €1,600,000.00 10/04/2017 31/03/2017 6W VS-0003 51A Old Kilmainham Road DN143078L Minister for Justice and Law 94 St. Stephen's Green, Dublin 2. €900,000.00 10/04/2017 31/03/2017 Reform VS-0006 O' Devaney Gardens North, 10 Ashford 63244F Dublin City Council Civic Offices, Wood Quay, Dublin 8 €8,750,000.00 10/04/2017 31/03/2017 Place, Arbour Hill VS-0007 O'Devaney Gardens South, Dublin 7 63244F; 30460F Dublin City Council Civic Offices, Wood Quay, Dublin 8 €3,150,000.00 12/12/2017 28/11/2017 VS-0008 St. Bricin's Military Hospital, O'Deavaney 191451F Dublin City Council Civic Offices, Wood Quay, Dublin 8 €3,250,000.00 06/06/2017 10/05/2017 Gardens/Moira Road VS-0011 Site at corner of Infirmary Road & 151686L; 198023F Dublin City Council Civic Offices, Wood Quay, Dublin 8 €8,000,000.00 12/12/2017 28/11/2017 Montpelier Hill, Dublin 7 VS-0013 32-40 Benburb Street Unregistered Benburb Street Property Company Law Society of Ireland, Blackhall Place, €8,650,000.00 14/08/2017 28/07/2017 Limited Dublin 7 VS-0019 Corner of Watling Street and Bonham 182062F The Digital Hub Development Crane Street, Dublin 8, D08 HKR9 €3,250,000.00 06/06/2017 10/05/2017 Street Agency VS-0020 28-31 Benburb Street. -

Looking Glass

Through the Looking Glass A Guide To Empowering Young People To Become Advocates For Gender Equality w National Women’s Council of Ireland 100 North King Street, Smithfield, Dublin 7 Ph: + 353 (0) 1 679 0100 W: www.yfactor.ie W: www.nwci.ie E: [email protected] Company No. 241868 Published November 2014 by National Women’s Council of Ireland ISBN 978–0–9926849–2–1 w Through the Looking Glass A Guide To Empowering Young People To Become Advocates For Gender Equality w Acknowledgements The Y Factor Design by www.melgardner.com 1 w Acknowledgements The National Women’s Council of Ireland Anita Ghafoor-Butt (IFPA); John Kenny would like to acknowledge all those who (Dundalk Outcomers); Gerard Rowe took part in The Y Factor Education pilot (Belong To); Alison Gilleland (INTO); project: Norah Harte (Scoil Chríost Rí, Portlaoise); Claire McAlinden (Bluebell Youth Project); • Bernadette White and the students John Williams, (Pavee Point); Ann Walsh of 4th year LCVP class (2013), St (National Youth Council of Ireland); Vincent’s Secondary School, Dundalk, Sarah Kearney (The Y Factor Steering The Y Factor Co. Louth. Group); Hilary Tierney (NUI Maynooth); • Bairbre Kennedy and the students Ifrah Ahmed, (United Youth of Ireland); of the Transition Year Programme Deirdre Toomey (Equality Authority); Paula (2013) Malahide Community School, Madden (Irish Traveller Movement); Mella Malahide, Co. Dublin. Cusack (CDVEC); Fiona Gallagher (Trinity • Una Killoran and the Leaving Comprehensive Ballymun). Certificate Vocational Programme NWCI would also like to acknowledge students (2013) of Lough Allen College, Emma Jayne Geraghty’s research piece Drumkeerin, Co. Leitrim. ‘Boxed In’, done in conjunction with • Fran McVeigh, Patricia Lematy, The Y Factor’s pilot education project, Michelle Crosby, Thomas McMahon, concerned with exploring the capacity of Sarah Kirke and the young women’s contemporary youth work in Ireland to group in Poppintree Youth Project, take a gender-conscious approach. -

Section 4: Resources and Services

Dublin City Parks Strategy 2019 – 2022 Section 4: Resources and Services Dublin City Centre 4.1 PARKS 4.1.1 Park Typology 4.1.2 Flagship Parks Dublin city has over 200 public parks of Dublin, like many other European cities, did not These parks are the top city parks and are defined various size, distribution and character within benefit from a pre-determined masterplan for the as significant visitor/tourist attractions because of its administrative area. These parks function to provision of its parks and open space. Instead, their historical context and location, their natural and create recreational, cultural, environmental and as the city grew organically each development built heritage or the high standard of design and social benefits to Dublin and the key function of era left its own kind of park, which we now horticultural presentation. They welcome thousands Park Services is to plan, design, maintain and collectively value and manage. of visitors each year. manage this resource. In order to analyse this resource, a typology of The key purposes and functions of Flagship City parks are not evenly distributed or of parks and open space is derived as follows: Parks are: consistent quality throughout the city. This • to provide natural environment connections, strategy assesses these issues so that it can • Flagship Parks specialised functions and features higher inform future parks provision,funding policy and • Community Parks (Grade 1) levels of activity for the entire city management. • Community Parks (Grade 2) • to be managed to the highest standard A parks typology is defined below to organise • Greenways • to act as a destination for tourists the array of existing parks, which are described • Other typologies: Graveyards, Incidental Open • to serve users from across the city and and assessed in terms of quantity, quality and Space, Housing beyond in particular parks accessibility.