The History of England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Uncrowned Lion: Rank, Status, and Identity of The

Robert Kurelić THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ External Examiner Budapest May 2005 I, the undersigned, Robert Kurelić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. I also declare that no part of the thesis has been submitted in this form to any other institution of higher education for an academic degree. Budapest, 27 May 2005 __________________________ Signature TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ____________________________________________________1 ...heind graffen von Cilli und nyemermer... _______________________________ 1 ...dieser Hunadt Janusch aus dem landt Walachey pürtig und eines geringen rittermessigen geschlechts was.. -

Part I Background and Summary

PART I BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY Chapter 1 BRITISH STATUTES IN IDSTORICAL PERSPECTIVE The North American plantations were not the earliest over seas possessions of the English Crown; neither were they the first to be treated as separate political entities, distinct from the realm of England. From the time of the Conquest onward, the King of England held -- though not necessarily simultaneously or continuously - a variety of non-English possessions includ ing Normandy, Anjou, the Channel Islands, Wales, Jamaica, Scotland, the Carolinas, New-York, the Barbadoes. These hold ings were not a part of the Kingdom of England but were govern ed by the King of England. During the early medieval period the King would issue such orders for each part of his realm as he saw fit. Even as he tended to confer more and more with the officers of the royal household and with the great lords of England - the group which eventually evolved into the Council out of which came Parliament - with reference to matters re lating to England, he did likewise with matters relating to his non-English possessions.1 Each part of the King's realm had its own peculiar laws and customs, as did the several counties of England. The middle ages thrived on diversity and while the King's writ was acknowledged eventually to run throughout England, there was little effort to eliminate such local practices as did not impinge upon the power of the Crown. The same was true for the non-Eng lish lands. An order for one jurisdictional entity typically was limited to that entity alone; uniformity among the several parts of the King's realm was not considered sufficiently important to overturn existing laws and customs. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The life and the autobiographical poetry of Oswald von Wolkenstein Robertshaw, Alan Thomas How to cite: Robertshaw, Alan Thomas (1973) The life and the autobiographical poetry of Oswald von Wolkenstein, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7935/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE LIFE AND THE AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL POETRY OF OSWALD VON WOLKENSTEIN Thesis submitted to the University of Durham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Alan Thomas Robertshaw, B»A. Exeter, March, 1973 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. CONTENTS Chapter Page Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iv I, INTRODUCTION 1 1o Summary of Research 1 20 Beda -

Dates & Events

Nailsea a Handbook of Dates and Events compiled by Peter Wright This ebook version, © Peter Wright and Nailsea & District Local History Society, PO Box 1089, Nailsea BS48 2YP, has been made available in July 2009, so that an individual may download and read this document, for private research purposes only. It must not be reproduced or passed to a third party without written permission of the copyright holders INTRODUCTION The booklet “ Nailsea – a Handbook of Dates and Events ” is still available from N&DLHS through this web site. The organiser of a Pageant planned to welcome the new Millennium to Nailsea asked me for some events that he could recreate as part of the activities. When unfortunately lack of support meant that the project had to be scrapped I had a number of items recorded from secondary sources that it seemed a pity to “waste”. I then decided to examine the books that I had in my possession and others available through the library service. I did not carry out any research on original documents. The books are listed in the “Sources section”. I took notes of each event that I came across and over a period of time the information increased far beyond my original expectation. The booklet on which this list is based was published by me in 1998. In producing the book in A5 format the entries were slightly truncated. This version which is in “A4” format has enabled me to go back to the original draft. This does mean that the size of the text and the amount of room for information has slightly increased but some fine tuning incorporated in the original printed edition may be missing. -

Code of 1771

This is a translation of the CODE OF 1771 (Chapter 15.120) as in force on 1 January 2019 This is not an authoritative translation of the Law. Whilst it is believed to be correct, no warranty is given that it is free of errors or omissions or that it is an accurate translation of the French text. Accordingly, no liability is accepted for any loss arising from its use. WHEREAS there was this day read at the Board a Report from the Right Honourable the Lords of the Committee of Council for the Affairs of Jersey and Guernsey dated the 26th of this instant, upon considering the annexed Collection or Code of laws agreed upon by the states of the Island of Jersey, and transmitted for His Majesty’s Royal approbation – His Majesty taking the same into Consideration, is hereby pleased, with the advice of His privy Council, to approve of ratify, and confirm the Said Collection or Code of laws, and to Order, that the same, together with this Order, be entered upon the register of the said Island and observed accordingly – And His Majesty Doth hereby declare that all other Political and written laws heretofore made in the Said Island, and not included in the Said Code, and not having had the Royal assent and confirmation, Shall be from henceforward of no force and validity. – And His Majesty doth hereby Order that no Laws or Ordinances whatsoever, which may be made provisionally or in view of being afterwards assented to by His Majesty in Council, Shall be passed but by the whole Assembly of the States of the said Island; And with respect to such -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

British History After 1603 Stuarts James I 1603-1625 Charles I 1625-1649 Interregnum 1649-1660 Charles II 1660-1685 James

British History After 1603 Stuarts James I 1603-1625 Charles I 1625-1649 Interregnum 1649-1660 Charles II 1660-1685 James II 1685-1688 William and Mary 1688-1702 Anne 1702-1714 King’s Own Tonnage and poundage Morton’s Fork Privy Council Parliament bicameral House of Lords House of Commons Knights of shire burghesses borough 3 Common law courts Court of Exchequer Court of Common Pleas Court of the King’s Bench Prerogative Courts Star Chamber Court of High Commission Church of England Anglican episcopal Primogeniture Nobility Gentry Professional middle class Yeoman Common laborers THE STUART AGE 1603-1714 1. Stuarts embrace 4 generations James I to Anne 2. One king beheaded, one chased out, one restored, one called from abroad 3. Two revolutions 4. Decline in power of the monarchy Features of Stuart 1. Tug of war between monarch and Parliament 2. Struggles of the Church High Anglicans Low Anglicans 3. Reform Rise of newspapers Rise of political parties Use of public meetings 4. Unification of England and Scotland 5. Establ. Of a worldwide empire James I 1603-1625 Count and Countess Marr 1597 Trew Law of a Free Monarchy Divine Right Millenary Petition 1603 Hampton Court Conference 1604 Presbytery Act of Uniformity Gun Powder Plot Guy Fawkes and Richard Catesby m. Anne of Denmark Elizabeth Henry Charles Henrietta Maria Duke of Buckingham George Villiers Petition of 1621 Union Jack St George (England) and St. Andrew (Scotland) Calvin Case 1608 Post nati Ulster Lost Colony of Roanoke Sea Dogs Virginia Company Southern Virginia Company Northern Virginia Company Jamestown Plymouth Nova Scotia New Foundland Bermuda St Kitts Barbados Nevis Is. -

I. Remembrances, 1671–1714

I. REMEMBRANCES, 1671-1714 [fol. 46V] Some few remembrances of my misfortuns have attended me in my unhappy life since I were marryed, which was November the 14., i6yi £67!, Novembr £4 Thursday, Novembr 14, i67i, and Childermas Day, I was privatly marryed to Mr Percy Frek by Doctter Johnson in Coven Garden, my Lord Russells chaplin, in London, to my second cosin, eldest son to Captain Arthur Frek and grandson to Mr William Frek, the only brother of Sir Thomas Frek of Dorsettshiere, who was my grandfather, and his son Mr Ralph Frek [was] my own deer father.1 And my mother was Sir Thomas Cullpepers daughter of Hollingburne in Kentt; her name was Cicelia Cullpeper. Affter being six or 7 years engaged to Mr Percy Freke, I was in a most grievous rainy, wett day marryed withoutt the knowledg or consentt of my father or any friend in London, as above. 1672, Jully 26 Being Thursday, I were againe remaned by my deer father by Doctter Uttram att St Margaretts Church in Westminster by a licence att least fowre years in Mr Freks pocttett and in a griveous tempestious, stormy day for wind as the above for raigne.21 were given by my deer father, Ralph Frek, Esqr, and the eldest of his fowre ' The Registers of St. Paul's Church, Covent Garden, London, ed. William H. Hunt, Harleian Society, 35 (1907), 49, indicates they were married on 14 November 1672. Freke confirms the 1671 date in an entry she adds to the West Bilney register and in her miscellaneous documents (below, p. -

Rockford Common Trail the Rockford Miles

Rockford Common Trail The Rockford Miles A C Pillow Mounds 4 5 B 3 Rockford Common 1 2 10 6 Rockford Little Whitemoor 9 Bottom 7 Bigsburn Hill 8 KEY Trail route Highwood Access route Footpath Brook Roads 1.7 – 2.5 miles / 45 minutes – 1.5 hours Woodland Trail route summary Buildings This trail has two routes, the main routes takes in a southern section (on unsurfaced 1 Stop spots rights of way with some gates and stiles), the other (shorter) route is via surfaced A Points of interest tracks. This route is more accessible for those with reduced mobility and/or making use of a ‘Tramper’ like mobility scooters. Parking Trail Stats: Access Circular Trail length 1.7 miles (2.7km) 2.5 miles (4km) Time to walk trail 45 minutes 1.5 hour Starting point of trail National Trust Car Park, Rockford Common. Car parking National Trust Car Park, Rockford Common Grid reference – SU164083. Terrain (hilliness) Mostly flat with a couple of Mostly flat with several steeper steeper sections. sections. Surface type/s Well-made gravel tracks Well-made gravel tracks and more minor grass and gravel tracks. Stiles / gates information One barrier passable by buggies/ Some stiles, gates. wheelchairs. Notes Do check yourself for ticks on your return to the car. Accessibility It is possible to follow a shorter Access route on well-made gravel tracks (although some Stop Spots require a short walk of the tracks). The extended circular route continues further south on more minor grass and gravel tracks where there are some gradients and has stiles and gates. -

The Medieval Parliament

THE MEDIEVAL PARLIAMENT General 4006. Allen, John. "History of the English legislature." Edinburgh Review 35 (March-July 1821): 1-43. [Attributed in the Wellesley Index; a review of the "Reports on the Dignity of a Peer".] 4007. Arnold, Morris S. "Statutes as judgments: the natural law theory of parliamentary activities in medieval England." University of Pennsylvania Law Review 126 (1977-78): 329-43. 4008. Barraclough, G. "Law and legislation in medieval England." Law Quarterly Review 56 (1940): 75-92. 4009. Bemont, Charles. "La séparation du Parlement anglais en deux Chambres." In Actes du premier Congrès National des Historiens Français. Paris 20-23 Avril 1927, edited by Comite Français des Sciences Historiques: 33-35. Paris: Éditions Rieder, 1928. 4010. Betham, William. Dignities, feudal and parliamentary, and the constitutional legislature of the United Kingdom: the nature and functions of the Aula Regis, the Magna Concilia and the Communa Concilia of England, and the history of the parliaments of France, England, Scotland, and Ireland, investigated and considered with a view to ascertain the origin, progress, and final establishment of legislative parliaments, and the dignity of a peer, or Lord of Parliament. London: Thomas and William Boone, 1830. xx, 379p. [A study of the early history of the Parliaments of England, Ireland and Scotland, with special emphasis on the peerage; Vol. I only published.] 4011. Bodet, Gerald P. Early English parliaments: high courts, royal councils, or representative assemblies? Problems in European civilization. Boston, Mass.: Heath, 1967. xx,107p. [A collection of extracts from leading historians.] 4012. Boutmy, E. "La formation du Parlement en Angleterre." Revue des Deux Mondes 68 (March-April 1885): 82-126. -

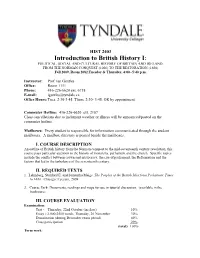

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading.